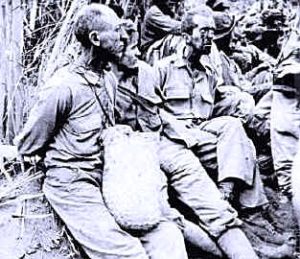

Douglas MacArthur and Jonathan Wainwright

Family Feud: A Tale of Two Generals

It has been said that "If you have one child you are a parent, two (or more) and you are a referee." Sibling rivalries are common in any family, and the family of America's veterans is no different. The term "Brotherhood" does not indicate that all is peaceful and calm or that there is an absence of disagreement. Brothers have been known to argue, feud, even fight each other. But brotherhood is a bond that is greater than the "family feuds" that erupt from time to time, and sooner or later brothers make up and get on with being brothers.

It has been said that "If you have one child you are a parent, two (or more) and you are a referee." Sibling rivalries are common in any family, and the family of America's veterans is no different. The term "Brotherhood" does not indicate that all is peaceful and calm or that there is an absence of disagreement. Brothers have been known to argue, feud, even fight each other. But brotherhood is a bond that is greater than the "family feuds" that erupt from time to time, and sooner or later brothers make up and get on with being brothers.

General George Armstrong Custer was so envious of his younger brother's two Medals of Honor, earned during the Civil War, that it caused some real tension. There are even reports that on at least one occasion when the younger showed up at a social event wearing both medals, the two went outside and engaged in fisticuffs. But the sense of brotherhood between the two was stronger than their sibling rivalry. Thomas Custer always loved the older brother and the two served together through several campaigns in the West. Eventually, the two brothers died together at the infamous Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Douglas MacArthur and Jonathan Wainwright were as similar, yet individually different, as any two "flesh and blood" brothers. Both were the sons of military families. MacArthur's father Arthur was the hero who received the Medal of Honor during the Civil War. Wainwright's father also was a career officer who had at one point even served under Arthur MacArthur's command.

Douglas MacArthur graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point at the head of his class in 1903. Three years later Jonathan Wainwright graduated from the same school with its highest honor, first captain of cadets. Both served in World War I, MacArthur leading the 84th Infantry Brigade and earning the Distinguished Service Medal and six Silver Stars. Wainwright saw less combat as a staff officer, though he became known for his frequent visits to the troops on the front lines. Wainwright also received the Distinguished Service Medal.

Both men were generals in the US Army and serving in the Philippines when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941. The months that followed and the differences in personality between the two would strain their brotherhood. Both would emerge historic figures, Douglas MacArthur characterized by historian/author William Manchester as the "American Caesar", Jonathan Wainwright remembered by his troops as "The Last of the Fighting Generals".

General MacArthur looked up from his desk at the tall, hard-bitten Cavalry general. The latter had always looked thin, hence the nickname "Skinny", first used when he had been a West Point cadet. The moniker had followed him through a 40-year military career. General Wainwright looked especially skinny now, after months of reduced rations. General Wainwright was commander of the North Luzon force in the Philippine Islands. General MacArthur had summoned him to the island fortress at Corregidor for an important meeting. The battle was not going well on the most important of the Philippine Islands, and things were about to get worse.

The Philippine Islands consisted of more than 7000 small islands in the South China Sea. Only a third of the islands were inhabited. The Island of Luzon in the north is the largest of the islands. Measuring a little over 40,000 square miles, it is about the same size as our state of Ohio. Manila Bay in the south-west part of the island is one of the world's finest harbors, bordered on the east by Manila, the Philippine Capitol City. Luzon had been "home" to General MacArthur off and on for many years, dating back to the days when his father had been military governor. As a promising West Point graduate, Douglas MacArthur's first assignment had been with an engineer unit in the Philippines, and it was here during that tour of duty he had first tasted combat.

The Philippine Islands consisted of more than 7000 small islands in the South China Sea. Only a third of the islands were inhabited. The Island of Luzon in the north is the largest of the islands. Measuring a little over 40,000 square miles, it is about the same size as our state of Ohio. Manila Bay in the south-west part of the island is one of the world's finest harbors, bordered on the east by Manila, the Philippine Capitol City. Luzon had been "home" to General MacArthur off and on for many years, dating back to the days when his father had been military governor. As a promising West Point graduate, Douglas MacArthur's first assignment had been with an engineer unit in the Philippines, and it was here during that tour of duty he had first tasted combat.

As the Japanese began their aggression for control of the Pacific, the Philippine Islands were key to their plans. Eight hours after the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, they attacked and virtually destroyed the American Air Force at Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Two days later they began landing troops on beaches in the northern part of the Island.

War Plan "Orange No. 3"

The Japanese threat to the Philippines had been recognized twenty years earlier, and a war plan for the defense of the Philippines was written in 1928. Known as "Orange No. 3" or "WPO-3", the defense of the islands called for a "tactical delay" of the invading enemy. Rather than battling the enemy throughout the island, if they could not defeat the invaders at their point of landing, the army would pull back to the peninsula of Bataan at the opening of Manila Bay. There they would delay the enemy for up to six months until reinforcements could be brought in to end the siege.

The Japanese threat to the Philippines had been recognized twenty years earlier, and a war plan for the defense of the Philippines was written in 1928. Known as "Orange No. 3" or "WPO-3", the defense of the islands called for a "tactical delay" of the invading enemy. Rather than battling the enemy throughout the island, if they could not defeat the invaders at their point of landing, the army would pull back to the peninsula of Bataan at the opening of Manila Bay. There they would delay the enemy for up to six months until reinforcements could be brought in to end the siege.

Mid-way in the opening of Manila Bay is the tadpole-shaped, rocky island of Corregidor. Less than 2 square miles in size, the island had been a fortress for many years. At the beginning of World War II it garrisoned soldiers to man artillery that could support the defense of Bataan should it ever be necessary to implement Orange No. 3. Initially, General MacArthur attempted to have his American soldiers and Philippine Scouts meet and defeat the invading Japanese as they landed on the island's northern beaches. Most of these were soldiers under the command of General Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright, at the age of 59 one of the oldest active generals in the United States army.

General Wainwright's Philippine Scouts fought courageously, but on December 22nd hope began to vanish. Japanese Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma waded ashore at Lingayen Gulf, just north of the Bataan Peninsula (indicated by the red starburst in the map above). Supported by 80 ships of the Japanese navy and 43,000 fresh troops, the Philippine Scouts were doomed. General MacArthur implemented Orange No. 3 and on December 26 he declared the Capitol of Manila to be an open city and abandoned it to the Japanese. As the American and Philippine forces began their withdrawal to Bataan, MacArthur set up his command post on the island of Corregidor. MacArthur moved his tactical operations into the quarter-mile-long Malinta Tunnel. It was from there he began to direct the "delaying action" that would keep the enemy at bay until supplies and reinforcements could arrive from the United States. It was a wasted effort, for reinforcement of the valiant defenders wasn't even a part of the military war plan.

War Plan "ABC-1"

Ten months before the attack at Pearl Harbor, British and American military tacticians had established a war plan known as "ABC-1". The agreement between the two nations specified that, in the event that there would be hostilities on two fronts involving both the Germans and the Japanese, both Allied powers would concentrate most of their military resources on defending Europe. Of course, the brave men fighting hunger, disease, and starvation in the dense jungles of the Philippines were not aware of ABC-1. For this reason, they believed President Roosevelt when he gave his year-end speech promising "the entire resources of the United States" would be committed to defending the Philippine Islands.

Two days later the Japanese took control of Manila. Meanwhile, more than 80,000 American and Filipino soldiers had withdrawn to the 500 square mile Bataan peninsula to maintain the delaying defense called for in Orange No. 3. Across the island, the Philippine Scouts, many of whom were not aware of Orange No. 1, continued to battle the enemy. It was a brave effort, many of them fighting with outdated World War I British Enfield rifles. Ammunition began to run out, food was in short supply, and disease depleted their ranks. But they, along with their brothers at Bataan stubbornly held out, anxiously awaiting the resources of the United States that had been promised by the President. Amazingly the soldiers stopped the Japanese advance at the Abucay line and held it for 12 days. Then, on February 8th, General Homma received an infusion of fresh troops from Tokyo. For the Americans and Filipinos, there were no fresh troops, no resupply. When Singapore fell on February 15, 1942, it was becoming apparent to the Philippine defenders that the United States would be sending no reinforcements. They were expendable.

Meanwhile, General MacArthur had received word from Washington that he should hold out against the Japanese as long as possible, then capitulation was permissible. MacArthur was livid. He had no intention of surrendering to the Japanese, had resolved himself to die in the defense of the Philippines. On February 22, General MacArthur said goodbye to Philippine President Manuel Quezon. As the popular President reluctantly boarded the submarine Swordfish to be evacuated to Australia, he removed his signet ring and placed it on MacArthur's finger. "When they find your body," he told his old friend, "I want them to know that you fought for my country." Remaining on the island with the General was his wife and 3-year old son. In the hold of the Swordfish were their personal effects with instructions for them to be held until claimed by the MacArthur's legal heirs.

Even as the Swordfish slipped out of Manila Bay to preserve the Philippine Presidency, President Roosevelt was pondering the impact on the National morale should the most decorated hero of World War One be killed or captured by the Japanese. The following day the Commander In Chief ordered General MacArthur to escape to the southern island of Mindanao, then from there to find asylum in Australia. As a United States Army officer, it was an order he could not refuse. As a patriot who loved the Philippine Islands, it was also an order that went against everything in which he believed. Finally the 62-year old, 4-star general decided to resign. He would leave Corregidor, but not as a retreating general going to Australia. Instead, as a civilian, he would make the brief boat ride from "The Rock" to Bataan and enlist as a volunteer in its defense.

In the days that followed, MacArthur's chief of staff, Major General Richard K. Sutherland convinced the General that the President was right. He argued that there were rumors that a Philippine relief force was being established in Australia and that the President had ordered MacArthur to Australia to build and lead that force back to the Islands to defeat the Japanese. The concept was reinforced by a telegram from Washington urging the General that "The situation in Australia indicates the desirability of your early arrival there." MacArthur responded that he would, reluctantly, depart Corregidor on March 15th.

Meanwhile, the Japanese suspected that an attempt would be made to evacuate the Philippine commander from the area, and they too realized the propaganda potential for his death or capture. They increased their patrols in the South China Sea, virtually unopposed for the US Pacific Fleet was still rebuilding from the devastation at Pearl Harbor. A full Japanese destroyer division was dispatched towards Manila Bay to prevent any evacuation of the general. The timetable had to be accelerated, and the only craft available to transport MacArthur and his family from Corregidor were four aging PT boats under the leadership of Lieutenant John Bulkeley. (Lieutenant Bulkeley would later receive the Medal of Honor for his heroic defense of the Philippines from December 7, 1941, to April 10, 1942.) Bulkeley and his PT boats would break out of Luzon as the sun went down on March 11th, taking with them General MacArthur. The Naval officers at Corregidor who were aware of the plan believed the General had about 1 chance in 5 of getting out successfully, and alive.

From the devastating attack that destroyed Clark Air Field eight hours after Pearl Harbor until March 11th, General Douglas MacArthur had encouraged the valiant defenders that if they could just hold on, reinforcements would be coming from the United States. For 90 days Philippine Scouts and American soldiers, despite disease, a shortage of food, lack of ammunition, obsolete and malfunctioning military hardware, and hostile jungle terrain had battled the well supplied invading Japanese. Manila had been sacrificed and 68,000 Filipinos, supported by nearly 12,000 American soldiers, had fallen back to the peninsula of Bataan to stall the Japanese war plans to break and enslave the Philippine Islands.

It was becoming increasingly apparent that, despite the promises of the American President, there would be no relief force for the Philippine Islands. They were expendable. The idea was further fostered by Japanese propaganda radio whose theme song taunted the defenders. The song was titled: I'm Waiting for Ships that Never Come In

March 11, 1942

"Jonathan, I want you to make it known throughout your command that I'm leaving over my repeated protests." General MacArthur said as he looked up at General Jonathan Wainwright. The tall, emaciated General the defenders of Bataan called "Skinny" promised that he would do just that. Douglas MacArthur had chosen his replacement in the Philippines. His Academy brother would assume command of all the Philippine troops upon MacArthur's departure. Wainwright would command from the Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor, while Major General Edward King would replace him as commander of the American Forces and Philippine Scouts defending Bataan. "Goodbye Jonathan," MacArthur continued. "When I get back, if you're still on Bataan, I'll make you a lieutenant general."

"I'll be on Bataan if I'm still alive," Wainwright replied.

As darkness fell over the South China Sea, Lieutenant Bulkeley slipped out of Corregidor in PT-41 to make the dangerous journey through waters controlled by the Japanese. It was a daring mission to ferry an American legend and hero out of harm's way. Through 560 miles of dangerous ocean and a near brush with a Japanese destroyer, General MacArthur arrived safely on the southern island of Mindanao on the morning of Friday, the 13th of March. Four days later the General arrived in Australia. It was there that he issued the statement that contained one of his two most famous lines: "The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary object of which is the relief of the Philippines. I came through and I shall return."

To the Filipino people, MacArthur was a hero. Through the dark years ahead they believed that, as he had promised, he would return. But the enemy powers sought to portray MacArthur differently. From Germany and Italy to Japan he was labeled in the media as a coward, a deserter, and the "fleeing general". MacArthur had been ordered out of Corregidor because the President was concerned about the negative impact his death or capture would have on the American public during the critical first year of the war. To counter the propaganda of the enemy, General George C. Marshall suggested awarding MacArthur the Medal of Honor. The President agreed, and the same award his father had received 80 years earlier was presented to General Douglas MacArthur in Australia on June 30, 1942. (Arthur and Douglas MacArthur became the only father and son in history to both receive the Medal of Honor.)

It is difficult to argue with those who point out that Douglas MacArthur's Medal of Honor was a political move. It is far less difficult to argue the point that it was not deserved. Since his first engagement with Philippine Outlaws after graduating from West Point, MacArthur had proved himself a man of courage. Acts of personal valor in both the Mexican Campaign (Vera Cruz) and during World War I could easily have resulted in a Medal of Honor award. Those historians who would negate his World War II award because it was a political award must also realize that the fact he had not previously been awarded the Medal for other actions was, in MacArthur's mind, political as well.

Back on the Philippine Island of Luzon, the situation continued to deteriorate. The Japanese, despite isolated pockets of resistance by Philippine Scouts scattered throughout the jungles, controlled the island. Their massive army, consisting of two full divisions of well-trained combat soldiers supported by two tank regiments, three engineer regiments, and several powerful artillery and anti-aircraft batteries, were virtually invincible. The Philippine defenders at Bataan were surrounded and without any support other than artillery fire from Corregidor. General King and his men were combat weary, demoralized by broken promises of resupply, and weakened by malnutrition and disease. Food was so short that the soldiers have reduced to one-fourth the recommended combat ration. Malnutrition made the soldiers even more susceptible to disease, and General King's medical units had virtually no medicines to treat the dying. Disease, exhaustion, and malnutrition were beginning to accomplish what tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers had tried for 90 days to achieve. The soldiers on Bataan had survived and resisted far beyond any expectation of human endurance.

The situation at Corregidor was no better. Here too, the soldiers were weary, wounded, malnourished, and diseased. From the Malinta Tunnel, General Wainwright did his best to direct the tactical aspects of the resistance. Unlike MacArthur, who had only once left the tunnel to visit troops on Bataan, "Skinny" made frequent visits to the peninsula to check on the status of his men...and to fight Japanese. In the months preceding his promotion to command of all forces in the Philippines, Wainwright had not only commanded the Philippine Scouts in I Corps, he had fought with them. On more than one occasion he had come under direct fire from enemy soldiers, watched men next to him die, and returned fire on the enemy. He was a unique kind of commander, perhaps indeed, the "Last of the Fighting Generals".

On April 9, 1942, the Japanese landed 50,000 fresh combat troops on the Island. Wainwright issued orders to General King to resist by all means. General King responded that he and his staff had determined his force was reduced to 30% of their efficiency. General Wainwright continued to order not only resistance but ordered a counter-attack to repel the new Japanese offensive. It was not to be. With less than two days' rations remaining, his troops paralyzed by exhaustion and disease, further resistance to the fresh Japanese offensive would have resulted in the slaughter of his beleaguered command. On April 9th General King surrendered, and Bataan fell to the Japanese.

The Bataan Death March

Most of the Philippine defenders were located near the southern Bataan city of Mariveles. Here the Japanese assembled their prisoners for the 55-mile march from Mariveles to the rail town of San Fernando. Here as many as 100 prisoners were loaded into boxcars measuring 8 x 40 feet, and taken 24 miles to Capas, Tarlac. The deadly trip culminated with the 6-mile march to the infamous Camp O'Donnell.

Most of the Philippine defenders were located near the southern Bataan city of Mariveles. Here the Japanese assembled their prisoners for the 55-mile march from Mariveles to the rail town of San Fernando. Here as many as 100 prisoners were loaded into boxcars measuring 8 x 40 feet, and taken 24 miles to Capas, Tarlac. The deadly trip culminated with the 6-mile march to the infamous Camp O'Donnell.

Hands bound, wounds untreated, sick and malnourished to the point where many could not even stand, the trek became known as the "Bataan Death March". More than 76,000 Philippine defenders, including 12,000 American soldiers, became prisoners with the surrender on April 9th. On the death march to Camp O'Donnell, the Japanese beheaded many who became too weak to continue the trip. Other prisoners were used for bayonet practice or pushed to their deaths from cliffs to amuse their captors with their screams. Young Philippine girls were pulled to the side of the road and repeatedly raped. Heartbroken mothers were known to spread human feces on their daughter's faces to make them less desirable to the enemy.

Actually, there was not one Death March, but a series of death marches that began with the surrender on April 9th and continued until April 24th. During the period there was a steady stream of American and Philippine P.O.W.s making the 5-10 day trip to Camp O'Donnell. Of the 80,000 defenders of Bataan, it is estimated that as many as 20,000...one in four...died on the infamous death march. (In the two months that followed it is estimated that as many as 1,500 Americans and 25,000 more Filipinos died at Camp O'Donnell.)

With Bataan now under Japanese control, the enemy turned their full attention to "The Rock". General Wainwright and his 26,000 troops at Corregidor were the last organized resistance on Luzon. In all, more than 400 fighter planes and bombing attacks were launched against the 2 square mile island. For almost a month, while the Japanese continued their wholesale slaughter of Bataan's valiant defenders during their infamous death march, Corregidor held. By May 6th the Philippine defenders had continued to fight the delaying action called for in Orange No. 3 for the full six month period determined necessary for resupply and reinforcement. The defenders had done their part, but now they knew there would be no resupply or reinforcement.

For long days and lonely nights, General Jonathan Wainwright had struggled to determine in his mind the best course of action. He was proud of his men and they had come to love, admire, and obey him. Finally, on the morning of May 6th, he notified them of his decision. "With a broken heart and with head bowed in sadness, but not in shame," he told his soldiers, today I must arrange terms for the surrender." At 10:15 A.M. he sent the last message from Corregidor to President Roosevelt. He told the President:

"There is a limit of human endurance and that limit has long since been passed. Without the prospect of relief, I feel it is my duty to my Country, and to my gallant troops, to end this useless effusion of blood and human sacrifice. With profound regret and continued pride in my gallant troops, I go to meet the Japanese commander.

"Goodbye, Mr. President."

At exactly noon on May 6, 1942, General Jonathan M. Wainwright surrendered to Japanese General Homma. A historian of the Civil War, Wainwright later said of that moment, "Suddenly, I knew how Lee felt after Appomattox.

The defenders from Corregidor were not marched north through Bataan. Instead, the Japanese shipped them across the bay to Manila where they were paraded in disgrace as a display of Japanese superiority. As a final humiliation for General Wainwright, he was forced to march through his defeated soldiers. Despite their wounds, their illness, their broken spirit, and shattered bodies, as the General passed among their ranks they struggled to their feet. It was their last show of respect for the last of the fighting generals.

In Australia, General MacArthur was furious. In his own mind, he had initially resolved to die fighting to defend the Philippines. The man he had selected to complete that mission when he had been ordered to leave Corregidor had let him down. On July 30, 1942, General George C. Marshall proposed that a Medal of Honor be awarded to the last of the fighting generals. It prompted an act of resistance to a Medal of Honor award, unprecedented in the Medal's history. General MacArthur wrote, in part:

The citation proposed does not represent the truth. As a relative matter award of the Medal of Honor to General Wainwright would be a grave injustice to a number of general officers of practically equally responsible positions who not only distinguished themselves by fully as great personal gallantry thereby earning the DSC but exhibited powers of leadership and inspiration to a degree greatly superior to that of General Wainwright thereby contributing much more to the stability of the command and to the successful conduct of the campaign. It would be a grave mistake which later on might well lead to embarrassing repercussions to make this award.

MacArthur's vehement opposition to Wainwright's proposed award both surprised and stunned General Marshall. He withdrew the recommendation, and while General MacArthur prepared to keep his promise to return to the Philippines, General Wainwright was left to suffer alone in a Japanese prison camp.

During his more than three years of captivity, General Wainwright suffered deprivation, humiliation, abuse, and torture at the hands of the Japanese. In his own mind, he feared the moment of his return, sure that he would be considered a coward and a traitor for his surrender at Corregidor. He knew nothing of the award that had been proposed, then shelved because of MacArthur's scathing objections. Throughout the period he struggled to survive. General Jonathan Mayhew Wainright was the highest-ranking American prisoner of war in World War II, and celebrating his 60th birthday in a POW camp in Manchuria, he was also one of the oldest.

During his more than three years of captivity, General Wainwright suffered deprivation, humiliation, abuse, and torture at the hands of the Japanese. In his own mind, he feared the moment of his return, sure that he would be considered a coward and a traitor for his surrender at Corregidor. He knew nothing of the award that had been proposed, then shelved because of MacArthur's scathing objections. Throughout the period he struggled to survive. General Jonathan Mayhew Wainright was the highest-ranking American prisoner of war in World War II, and celebrating his 60th birthday in a POW camp in Manchuria, he was also one of the oldest.

On October 25, 1944, General Douglas MacArthur waded ashore at Leyte to announce, "People of the Philippines, I have returned." Almost a year of bitter fighting remained for Allied forces in the  Pacific. Then, on August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. On August 14 the Japanese announced that they would surrender. The final documents of surrender would be signed in Tokyo Harbor on September 2nd. General MacArthur would preside over the historic event

Pacific. Then, on August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. On August 14 the Japanese announced that they would surrender. The final documents of surrender would be signed in Tokyo Harbor on September 2nd. General MacArthur would preside over the historic event  and sign on behalf of the President of the United States.

and sign on behalf of the President of the United States.

On August 19, General Wainwright learned that the war had ended. He would finally be going home. He was flown first to Yokohama, where he arrived looking tired and gaunt on August 31st. Despite his earlier disappointment at the surrender at Corregidor, it was General Douglas MacArthur who met him. The two embraced as cameras caught the historic moment. (The photo at the top of this page is one that was taken that day.

On September 2nd General MacArthur boarded the USS Missouri in Tokyo Harbor to meet the Japanese. On the table before him were the documents of surrender and several fountain pens with which he would sign. As he approached the table he spoke into the microphone, "Will General Wainwright and General Percival step forward and accompany me while I sign." It was a special tribute by MacArthur to the last of the fighting generals. Looking gaunt and weak, Wainwright proudly stood at rigid attention next to the British general Percival.

When the moment arrived to sign counter-sign the historic documents, MacArthur picked up the first fountain pen and scribbled his signature. Then he turned and handed that first pen to General Jonathan Wainwright. Skinny later said it was a "wholly unexpected and very great gift."

Promoted to Lieutenant General, Jonathan Wainwright returned home not to the shame he expected as the commander who had surrendered at Corregidor. Instead, he was welcomed with cheers, ticker-tape parades, and an outpouring of love and affection. President Truman sent word that he wanted to meet with the general.

Promoted to Lieutenant General, Jonathan Wainwright returned home not to the shame he expected as the commander who had surrendered at Corregidor. Instead, he was welcomed with cheers, ticker-tape parades, and an outpouring of love and affection. President Truman sent word that he wanted to meet with the general.

Wainwright and his wife flew into Washington, D.C. on the morning of September 10th. They were met by General Marshall to escorted them to the White House. There they visited briefly with President Truman in the Oval Office. Suddenly, as if it were an afterthought, the President told  General Wainwright, "Let's step outside in the Rose Garden to continue this conversation." The two stood and the President took the General by the arm to escort him outside. General Wainwright was surprised to find the Rose Garden filled with military officials, press reporters, and spectators. His first thought was that the President wanted him to give a speech.

General Wainwright, "Let's step outside in the Rose Garden to continue this conversation." The two stood and the President took the General by the arm to escort him outside. General Wainwright was surprised to find the Rose Garden filled with military officials, press reporters, and spectators. His first thought was that the President wanted him to give a speech.

The speech that day was to be the president, however. As President Truman stepped to the microphone and began to read, it dawned on General Wainwright what was about to happen. When the President had read the citation he turned to the last of the fighting generals and placed the Medal of Honor around his neck. On September 5, General Marshall had revived his recommendation, and the President quickly approved the award. This time there were no objections.

The speech that day was to be the president, however. As President Truman stepped to the microphone and began to read, it dawned on General Wainwright what was about to happen. When the President had read the citation he turned to the last of the fighting generals and placed the Medal of Honor around his neck. On September 5, General Marshall had revived his recommendation, and the President quickly approved the award. This time there were no objections.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED