The "Frozen Chosin"

Written by C. Douglas Sterner

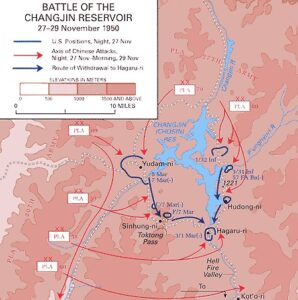

In November 1950, eight thousand fighters - most of them U.S. Marines - struggled to survive the coldest North Korean winter in 100 years. Surrounded by 120,000 Chinese soldiers, their only lifeline was a 15'-wide, steep mountain road they called the MSR (Main Supply Route) that led to the port city of Hungnam. From Yudam-ni at the northwest corner of the Chanjin Reservoir, the MSR was a dangerous, 78-mile journey to the Sea of Japan. The trip was made far more difficult by the massive enemy force surrounding it. The withdrawal, the longest in American military history, would take 13 days and cost many lives. Those who didn't understand what was happening called it a "retreat", while one American general simply said, "We're attacking in a different direction." How you assess what happened over those two freezing weeks in North Korea depends on your perspective.

In November 1950, eight thousand fighters - most of them U.S. Marines - struggled to survive the coldest North Korean winter in 100 years. Surrounded by 120,000 Chinese soldiers, their only lifeline was a 15'-wide, steep mountain road they called the MSR (Main Supply Route) that led to the port city of Hungnam. From Yudam-ni at the northwest corner of the Chanjin Reservoir, the MSR was a dangerous, 78-mile journey to the Sea of Japan. The trip was made far more difficult by the massive enemy force surrounding it. The withdrawal, the longest in American military history, would take 13 days and cost many lives. Those who didn't understand what was happening called it a "retreat", while one American general simply said, "We're attacking in a different direction." How you assess what happened over those two freezing weeks in North Korea depends on your perspective.

It is adversity that demands valor, a trial that demonstrates the highest levels of brotherhood. The Marines at the Chanjin Reservoir, identified on Japanese maps as the Chosin Reservoir, pulled together to ensure the success of the withdrawal. What many people might have considered being the darkest two weeks in Marine Corps history may have, in fact, become the Marine Corps' defining moment. With their backs to the wall, the men of the 1st Marine Division pulled together to accomplish the impossible. Their teamwork cemented a band of brothers who came to call themselves: "The Frozen Chosin".

"Home by Christmas"

The war in Korea began early on the morning of Sunday, June 25, 1950, when nearly one hundred thousand soldiers from the North crossed the 38th parallel that divided South Korea from Communist North Korea. Unprepared and overwhelmed, the Army of the Republic of Korea was almost destroyed and the South's capital city of Seoul fell to the invaders within days. Six days later soldiers of the American 24th Infantry arrived to assist the Republic of Korea (ROK) Army in the defense of their homeland, but it was too little, too late. By early fall, the future of South Korea was uncertain.

On September 15th, the United Nations forces, led by General Douglas MacArthur and consisting primarily of United State Marines, made the daring landing at Inchon and the tide of battle began to turn. Within weeks it was the North Korean army that was almost destroyed, giving up the cities they had taken earlier and falling back in full retreat behind the 38th parallel. The victory had been swift and decisive, returning control of South Korea to its rightful owners. General MacArthur wanted to follow with steps to ensure their future as well.

The divided peninsula of Korea rests between the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea. Its only neighbor sits along the northeast boundary of North Korea. That border is the Yalu River, and that neighbor is the Chinese Manchuria. Fearful of an American sweep into the North following the successful landing at Inchon, the Chinese government issued a warning that if General MacArthur sent his troops north of the 38th parallel, they would be met by soldiers of the Chinese Army. Military planners doubted that the threat was real, and sent the Allied forces north to "neutralize" the forces of North Korea and ensure that a repeat of the June 25th invasion would not occur. On October 9, 1950, the first elements of American military units crossed the 38th parallel to take the battle home to the North Koreans. Five days later two Chinese Armies consisting of 12 Divisions (120,000 soldiers) crossed the Yalu River undetected.

For weeks the Chinese soldiers moved into the rugged mountains of North Korea, traveling only under cover of night and camouflaging their positions during the day. As MacArthur's forces moved north in a two-prong front, the 8th Army moved toward the Yalu River from the western side of the peninsula and the 10th Army on the eastern coast, the Americans didn't realize a well-hidden, massive force was waiting to pounce on them. On October 25th the hidden enemy attacked, surprising forces of the ROK army. In three days they destroyed four ROK regiments. Still, American war planners were hesitant to believe the Chinese Force was more than just a few scattered units of North Korean soldiers, and committed the men of the 8th and 10th Armies to an offensive campaign to end the war and, as General MacArthur promised, get American soldiers "Home by Christmas".

While the 8th Army was moving up the western edge of North Korea, on the east coast the port city of Wonsan was taken, followed by the city of Hangman. From there, members of the 1st Marine Division would move northwest on the MSR to the vital Chosin Reservoir. The village of Koto-ri was almost mid-way from Hungnam to the north edge of the reservoir, and the 4,200 Marines of the 1st Marine Regiment set up there. The 1st Marine Division Headquarters was established at Hagaru-ri, a small village at the southern tip of the reservoir. By November 27th 3,000 Americans inhabited Hagaru-ri, most of them engineers, clerks, and supply personnel.

The combat troops, warriors of the 5th and 7th Marine Regiments, moved 12 miles northwest to the village of Yudam-ni. From here they were to travel west, crossing the rugged mountains to link up with the 8th Army. That was the plan, but the plan hadn't factored in two unexpected obstacles:

- Between 120,000 and 150,000 well-hidden Chinese Communist soldiers, and

- The worst winter weather conditions in 100 years.

One can only guess how cold it became in the high Taebaek mountains around the Chosin Reservoir during the winter of 1950. At one regimental headquarters, the thermometer fell to minus 54 degrees. American Marines shivered in their foxholes, while vehicle drivers were forced to run their engines 24-hour a day. If the engine were shut down, chances were high that it couldn't be restarted. A rare hot meal could quickly freeze in the time it took a Marine to move from the serving line to a place where he could sit down to eat it. Then, to add to the misery, the Chinese launched their surprise attack.

The "Home by Christmas" offensive officially began on November 24th, the day after Thanksgiving. In the west the 8th Army began their push to the Yalu, only to be surprised by an unbelievable swarm of hidden Communist soldiers. Within days the CCF (Chinese Communist Forces) destroyed the ROK II Corps, leaving the 8th without flanking cover or general support. The badly battered 8th Army was ordered to fall back on November 19th, a 275-mile withdrawal that in six weeks cost 10,000 casualties.

On the eastern slope of the Taebaek Mountains, most of the Marines were unaware of what was happening in the west, or just how badly outnumbered and surrounded they were. The first indication came on the morning of November 27th as two companies of the 5th Marines began the push from Yudam-ni westward. Before noon they ran into an enemy roadblock. Unaware of the number of enemies around them, the Marines engaged the Chinese, destroying the roadblock. Then the enemy fire began to rain on them from all directions. The Marines knew they were in for a fight, one that lasted for nearly four hours. Then, when the firing subsided, the Marines attempted to dig in. The intensity of the battle convinced them that they were facing more than straggling units of North Korean soldiers. They knew the enemy would attack again, in force, under the cover of darkness. They did!

"The American Marine First Division has the highest combat effectiveness in the American armed forces. It seems not enough for our four divisions to surround and annihilate its two regiments. (You) should have one or two more divisions as a reserve force."

-Mao Zedong's orders to Chinese General Song Shilun

As night fell on November 27, tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers came out of hiding, attacking American soldiers and Marines at all points around the Chosin Reservoir. The two companies dug into the west of Yudam-ni were shivering from the cold in make-shift foxholes when the overwhelming force attacked. In the darkness the Chinese swarmed the hill, coming within yards of the embattled Marines to toss grenades among them with deadly effectiveness. In one sector of the American perimeter, protected by two machine guns, the horde quickly overran one of the key defensive positions. When a grenade landed near the only remaining machine gun, Staff Sergeant Robert Kennemore recognized the danger to nearby soldiers, as well as the gun emplacement. Quickly he stomped his foot on the grenade to push it into the snow, the subsequent blast throwing his body into the air.

The Marines somehow held through the night, but their heavy losses were quickly visible in the breaking daylight. For S/Sgt Kennemore the cold may have been a lifesaver. He was found, the stumps of his legs frozen in blood-caked snow, still alive. Others were not so fortunate. And it was only the beginning.

From November 27th to December 10th, American soldiers and Marines would find themselves in a battle unlike any other in history. Survival would call for leadership, teamwork, and immense courage. From it was born a brotherhood perhaps unmatched by veterans of any other battle. During the horrible 14 days that followed "LIFE" magazine photographer David Duncan, himself a Marine Corps veteran of World War II, captured many heart-rending images. None, perhaps, was quite as poignant as the one at left. Even more, telling was the three simple words spoken by this soldier.

Upon capturing the image with his camera, David Duncan couldn't help asking this soldier, "What would you like for Christmas?" His simple answer echoed the hope of so many young Marines facing a hopeless situation at the Chosin Reservoir. He replied: "Give Me Tomorrow."

The hope for any tomorrow lay in the Marines' ability to support each other. Eight thousand troops from the 5th and 7th Marines were at the northwest corner of the Chosin Reservoir at Yudam-ni. Their only hope of support was provided by the 3,000 clerks and supply personnel 14 miles south at Hagaru-ri. The lifeline was the MSR, winding its way through the snow-covered mountains. If the MSR fell to the Chinese, the 5th and 7th Marines would be cut off....trapped. To prevent this, Company F (Fox), 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Division was sent to the high mountains of the 3-mile long Toktong Pass, almost mid-way between Yudam-ni and Hagaru-ri.

Monday, November 27th

Captain Bill Barber had only been in Korea for a month, but he was no "rookie company commander". He had proved his leadership abilities and courage five years earlier at Iwo Jima, where he was awarded the Silver Star. On November 27th Captain Barber and his 240 Marines were moved by truck to the Toktong Pass, where Barber found a high ridge overlooking the MSR. As night fell his Marines tried desperately to break through the frozen ground to dig foxholes. Their position, dubbed "Fox Hill", was going to be home for a while.

At 2:30 in the morning on November 28th, while Staff Sergeant Kennemore lay bleeding in the snow miles north of Barber's company, the Chinese swarmed Fox Hill. Swooping in from their hidden positions in the mountains, the Communist soldiers surrounded Barber's Marines. Wave after wave came at Barber throughout the early morning, threatening to overrun Fox Hill, but the Marines held. Many had been roused from their sleeping bags by the surprise onslaught and fought for hours in their bare feet. Wounded Marines ignored serious injuries to continue the fight. One of them, Private Hector Cafferata, fought a lone battle to keep the fanatical Communists from over-running his position. As daylight dawned, an enemy grenade landed in a shallow trench where the more seriously wounded had been moved. Cafferata rushed forward and grabbed the grenade, lobbing it away to save the wounded Marines. The heroic action cost him serious wounds to his hand and arms, but even those wounds weren't enough to stop Cafferata. He continued to resist, to battle the enemy, until wounded by a sniper bullet.

Daylight signaled the potential for the Marines to receive air support, and the Chinese pulled back. On the first night on Fox Hill, Barber's company had lost 20 men killed, one out of five wounded. The withdrawing Chinese left 450 dead on the rocky slopes of Fox Hill. But they would return.

As the Chinese soldiers were simultaneously attacking Yudam-ni and Fox Hill near the Toktong Pass, other CCF elements unleashed early morning assaults throughout the entire region. On the eastern side of the Chosin Reservoir, Army Lieutenant Colonel Don Faith watched as his 3,000-man force crawled into their sleeping bags to escape the sub-zero Korean night. Most of Faith's force, dubbed "Taskforce Faith", consisted of soldiers from the Army's 21st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. As they settled in for the night, they had no idea they were surrounded by an overwhelming number of enemies. As they slept, the enemy slipped quietly across the snow and into their midst. By the time the sleeping soldiers were awakened to the attacking horde, many of their comrades had been quietly overcome and killed and the Chinese were inside the perimeter. A fierce battle, often hand-to-hand, raged on until the sun began to rise.

Lieutenant Colonel Faith's leadership that first night was essential to maintaining order and organizing the resistance that allowed his task force to survive. The following day Faith reported that his soldiers had been attacked by two Chinese divisions. His task force had been ordered to advance to the Yalu River, but now Faith was concerned that his troops might not survive the force mustered around him at the Chosin Reservoir. General Almond flew in during the day to review the situation with Ltc Faith and quickly dispelled any mention of Chinese soldiers in the area, much less two divisions. He ordered Faith to continue his mission, pinned a Silver Star to Faith's jacket, and then flew back out. As the general's helicopter disappeared in the distance leaving Lieutenant Colonel Faith with a sense of impending disaster, the disgusted leader took the medal from his jacket and threw it into the snow.

Wednesday, November 29th

Lieutenant Colonel Faith expected the worst as night fell on November 28th, but his force was spared that night. Captain Bill Barber's wasn't. The Chinese wanted to control the Toktong Pass, isolating the Marines at Yudam-ni for annihilation. To do that they had to dislodge what remained of Barber's company. A mortar barrage softened up the defenses at Fox Hill. Then the CCF attacked at 2 o'clock in the morning, breaking into the small perimeter and engaging Barber's valiant Marines in desperate, personal combat. Barber rallied his men, shouting orders in the darkness and moving from position to position encouraging his men and engage the enemy. When enemy fire ripped into Captain Barber's leg he quickly stuffed a handkerchief into the wound to stem the flow of blood. Then he continued to hobble from position to position, alternating between encouraging his Marines to resist, and continuing to rain devastating fire on the encroaching enemy.

Meanwhile, back at Hagaru-ri, engineers, clerks, and other support personnel suddenly found themselves operating as infantry. The CCF had begun a series of nightly probes and attacks on the small headquarters garrison, and survival demanded that every man, even the wounded, fight for their life. Shortly after midnight signaled the beginning of the new day, the CCF had taken control of much of East Hill just outside Hagaru-ri. The high hill was critical to the defense of Hagaru-ri, but the defense of the hill had fallen to soldiers more accustomed to building things or moving material, than firing rifles and throwing grenades. Many had fought bravely, dying on the slopes of East Hill. Others fled back down the hill in terror. Somehow, East Hill had to be wrested back from the CCF. At Hagaru-ri Major Reginald Myers was dispatched to organize the broken remnants of Americans that were falling back in panic.

Myers wasn't polite about forcing reluctant clerks back towards the hill they had abandoned in panic. He gathered the rag-tag force around him with threats and sheer command leadership, finally managing to put together a force of 300 men. At their head he led the way back to East Hill, urging his force forward through the early morning darkness and falling snow. As enemy fire raked into his force, Myers watched man after man falls at his side. So thin was his force, he couldn't spare stretcher-bearers to carry the wounded back down the hill. They had to lay where they fell.

As morning broke the winter skies, Myers and his force had almost reached the crest of East Hill. Though down to less than a hundred men, Myers urged them to attack, leading the way himself. The enemy was too well-entrenched. Finally, Major Myers pulled his few survivors back into a defensive line and used the dawn of the new day to call airstrikes in on the CCF holding the hill's summit. He had been promised that reinforcements were coming from Koto-ri if he could just hold on through the day. Myers wasn't sure his meager force could repel another enemy attack but had little choice. He and his men dug in to wait for "the cavalry" to arrive and save the day.

The "Cavalry" was Task Force Drysdale, a 250 man element of the 41st Royal Marine Commandos under British Lieutenant Colonel Donald Drysdale based back at Koto-ri. Task Force Drysdale, supported by Company G, 3 Battalion, 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division planned to leave Koto-ri on the morning of the 29th to fight their way into Hagaru-ri to reinforce the headquarters there. What the task force hadn't anticipated was that first, they would have to fight their way out of Koto-ri. Leaving shortly after morning broke the skies, by noon they had only advanced two miles. It had been a bitterly fought advance that had cost many lives and gained little ground.

Company G's commanding officer, Captain Carl L. Sitter finally fought his way to link up with Ltc Drysdale, where the two held a council. They decided the ridge-by-ridge battle to reach Hagaru-ri would only result in the meaningless slaughter of their men. More than 150 vehicles had left Koto-ri with the task force, supported by more than two dozen tanks. Drysdale and Sitter loaded their Marines on the vehicles and, with the tanks leading the way, proceeded forward on the MSR while the CCF lined the ridges on both sides to rain deadly fire on them. The task force pushed ahead gaining a mile an hour, Marines dying with every yard. Captain Sitter's jeep was destroyed, the driver killed, but the company commander managed to survive. It was fortunate for the column, for as the afternoon wore on Lieutenant Colonel Drysdale was seriously wounded and command of the column fell to Sitter.

Sitter did his best to organize the task force, fighting each roadblock that arose and skirmishing with enemy soldiers on all sides. At one roadblock the enemy was close enough to throw a grenade into a truck filled with American Marines. Marine Private First Class William Baugh recognized the danger, knew that in seconds the grenade would explode to kill or seriously wound every man aboard. He also realized his shouted warning wouldn't be enough, and did what had to be done, throwing his own body on the grenade to absorb the full blast and spare his comrades. Seriously wounded, he died during the night.

The twelve-mile trip to Hagaru-ri took 12 hours. When finally the column had fought their way in to reinforce the battered command post a few hours before midnight, only 160 of Sitter's 270-man Company G remained to crawl exhausted into their sleeping bags. A few hours after midnight the wounded Drysdale arrived with the remainder of his Royal Marines. His unit had been cut in half by the desperate attempt to break through the Chinese and reach Koto-ri.

At Fox Hill, Captain Barber's beleaguered Marines faced a third straight night of horror as the enemy came again. Captain Barber ignored the pain from the bullet wound in his leg to hobble from position to position to encourage his warriors. Less than 90 men remained of his 240-man company, but Barber wouldn't let them go down without a fight. As the Communists swarmed Fox Hill that night he shouted orders, urged his men to resist, and continued to fight the waves of enemy soldiers. When an enemy bullet shattered his remaining good leg, Barber called for a stretcher. Unable to walk among his men any longer, he ordered the stretcher-bearers to carry him to the most tenuous positions in the battle, where he continued to lead his men, prostrate on the stretcher. There was no "quit" in Captain Bill Barber, and his own tenacity and courage gave his embattled Marines new hope. Against overwhelming odds, for the third night in a row, they held Fox Hill.

East of the Chosin Reservoir, Task Force Faith was hit again. The day before Lieutenant Colonel Faith had learned how serious the battle had become at Hagaru-ri and knew that there would be no relief for his battered force. Task Force Faith was on its own. After four hours of battle, shortly after 2 A.M. on November 30th, Lieutenant Colonel Faith ordered a withdrawal to the south. More than one hundred wounded were loaded on the remaining vehicles as he assembled what remained of his 3,000 man force in a ragged column attempting to break through to safety in the darkness while surrounded and taking fire from all directions.

In just three days the battle at the Chosin Reservoir had turned into a massacre. Like the infamous "Charge of the Light Brigade", American soldiers and Marines had found themselves in "the jaws of death" because someone (in military planning) had blundered, refusing to believe that the Chinese could have secretly moved so vast a force into North Korea.

For the soldiers and Marines at the Chosin, it didn't matter who was at fault. They had been ordered in, and they had followed their orders. Now, it was time to pull together to make the best of their bad situation. The Chinese had attacked with one mission, not to just defeat the Americans or send them out of North Korea in retreat, but to completely annihilate the First Marine Division.

Breakout From The Frozen Chosin

As it became apparent that the soldiers and Marines at the Chosin were facing an enemy that had surrounded them and outnumbered them more than 10 to 1, and in the face of similar opposing forces facing the 8th Army in the west, the drive to the Yalu halted and a withdrawal was finally ordered. Hagaru-ri would do its best to hold while the 5th and 7th Marines withdrew from Yudam-ni, then they would continue together with the forces from Hagaru-ri on the 12 mile stretch of the MSR to Koto-ri. From there the combined forces would move on to evacuation ships waiting in the Sea of Japan at Hungnam.

Back home the news media began referring to the withdrawal as a "retreat", something no Marine, much less any survivor of the battle at the Chosin Reservoir would ever utter. A retreating force usually withdraws in panic, soldiers running in all directions without order, seeking to save themselves. That didn't happen at the Chosin. Instead of running from the enemy, soldiers and Marines had repeatedly fought their way into the trap, with full knowledge of what lay ahead. On Fox Hill, Bill Barber had placed his company in the middle of the opposing force, simply because he knew how critical it was to keep the MSR opened. In the east, the column from Task Force Faith was fighting its way back towards the embattled soldiers at Hagaru-ri. From Koto-ri, Task Force Drysdale had jumped "from the frying pan into the fire". Rather than withdrawing to Hungnam, the Marines in Captain Sitter's company had literally fought their way into the surrounded camp at Hagaru-ri. Before the Marines could fight their way out, they had to fight their way in to link up with their surrounded comrades.

At Hagaru-ri General O.P. Smith quickly pointed out that the Marines weren't retreating, they were simply: "Attacking in a Different Direction"

Lieutenant Colonel Raymond G. Davis assembled his 800 men for a dangerous trip. It wasn't a withdrawal, they were going to fight their way into the middle of the mountains where the CCF forces waited in their hidden sanctuary. High above Toktong Pass, Bill Barber and the remnants of his valiant Marines were cut off, surrounded, and taking new casualties nightly. If there was going to be a withdrawal, no one, including Bill Barber, would be left behind.

Lieutenant Colonel Raymond G. Davis assembled his 800 men for a dangerous trip. It wasn't a withdrawal, they were going to fight their way into the middle of the mountains where the CCF forces waited in their hidden sanctuary. High above Toktong Pass, Bill Barber and the remnants of his valiant Marines were cut off, surrounded, and taking new casualties nightly. If there was going to be a withdrawal, no one, including Bill Barber, would be left behind.

Even as Captain Sitter's tired Marines were bedding down after their 12-hour battle to reach Hagaru-ri, Davis' Marines were preparing for a cold night in the North Korean mountains. No one knew if Barber could hold out one more night, but Davis would do his best to break through to pick up whatever "pieces" remained of Fox Company.

Meanwhile, Task Force Faith continued to move slowly towards relief, facing constant enemy roadblocks and attacking the fire. When Lieutenant Colonel Faith ordered the withdrawal at 2:00 A.M., the ragged column had begun to assemble for the trek to safety. What remained of Task Force Faith was held together only by sheer "guts" and the valiant leadership of the commander for whom the force was named.

With daylight on the morning of November 30th, it seemed that every Marine was either trapped and surrounded or fighting his way into that trap to rescue his brothers. At Hagaru-ri the exhausted Captain Sitter was awakened with new orders. "Take East Hill!"

After a 12-hour flight, the day before that had almost cut the company in half, it was a formidable order. But Sitter knew that somewhere out there on East Hill, surrounded and fighting for survival, was Major Reginald Myers. He rousted his exhausted Marines from their sleeping bags and moved out with the dawn. Somewhere around noon his force found what remained of Myer's rag-tag force and linked up with them. Then, under the direction of Myers and Sitter, the soldiers and Marines continued their assault on the enemy.

By nightfall, Sitter believed he could control enough of East Hill to keep the Chinese from mounting a successful attack on Hagaru-ri. His Marines dug in for the night, prepared to hold out against whatever the enemy threw at them. They were the last line of defense for Hagaru-ri, already stretched thin and surviving only on "grit and determination". The enemy came, not just in force, but in waves. The continuous attacks through the night quickly depleted the dug-in Marine's ammunition. Sitter sent an element down the hill for more, then continued to fight through the night. Wounded repeatedly, Sitter was determined to preserve what remained of Company G and keep control of East Hill as well. It was an impossible task, but somehow, he got it done. Daylight found his valiant force had done the unthinkable. It was the morning of December 1st, and Sitter would hold out for four more days before being relieved. When he finally prepared to leave Hagaru-ri, only 96 men remained to move out to safety with him.

Amazingly, Barber too had survived a fourth straight night of attacks at Fox Hill. Davis continued to lead his rescue force through the mountains, engaging the enemy throughout the day. By nightfall, he was close, but not close enough. Barber would have to hang on for one more night.

After fighting through the night, Task Force Faith was almost decimated. The battle didn't end with the dawning of daylight that first day in December. Roadblocks met the column at every turn. From the mountains on either side of the battered soldiers, the Chinese Communist Forces fired indiscriminate death on Task Force Faith. It was especially dangerous for the wounded, lying unprotected in the few remaining vehicles and unable to move to cover when a new volley of lead rained in. At one roadblock Faith called for air support. Errant napalm fell on some of the American soldiers creating panic and death. As the column struggled for any sanctuary, Faith was wounded and died that night. In a full-scale panic, his force disintegrated and ran into the mountains. Over the following days, some stragglers managed to find their way to Hagaru-ri...in all, perhaps 500 of them. Five out of every six men in Task Force Faith was either killed or captured. Those captured were never heard from again.

Late in the afternoon on 1 December 1950, because enemy aggressors at Yudam-ni surrounded his company, the Marines were ordered to move toward Hagaru-ri. By the time they reached Hill 1520 (Hill number shows elevation in meters), three miles southeast of Yudam-ni, it was very dark and the temperature averaged -40 degrees. The companies relocated a few times, and then back to a knoll between two rugged mile-high mountains where grenades, machine guns, and rifle fire bombarded them. Staff Sergeant William Windrich led a rifle squad of twelve men to meet the enemy head-on, armed with an M-2 carbine. Seven of his men were wounded or killed before they reached the forward position they were to defend.

Windrich was also wounded in the head by a bursting grenade. As blood gushed down his shoulder and back he moved his remaining men into a tight fire group. Then he ran to the company command post, drafting a small group of volunteers, and led them to evacuate the dying and wounded. Assuming command of what was left of a platoon, Windrich once more took up defensive positions. Now shot in both legs, he kept fighting, always refusing medical attention. For a long time, he crawled in the snow, back and forth between his men shouting words of encouragement, deploying his forces, and helping to throw back the attackers.

Only after the communist had been beaten off on the morning of December 2 did Staff Sergeant Windrich collapse and die due to the bitter cold, excessive loss of blood, and severe pain. In the end, two officers and eighteen enlisted men lived, to stagger down the mountain to be with the rest of the column headed toward Hagaru-ri. Windrich was not there! They could not take his body down the treacherous mountain terrain.

From a distance, Lieutenant Colonel Davis could hear the sounds of battle throughout the night of December 1st and into the morning of the second. He hoped and prayed that Barber could hold out one more night, sure that if his own force could survive the constant attacks of the enemy, they would reach Barber with daylight. Somehow Barber did survive that fifth night, and shortly before noon on December 2nd he welcomed Davis and his Marines to Fox Hill. From its heights, the two could look down on the MSR as 8,000 men from the 5th and 7th Marines moved from Yudam-ni to Hagaru-ri. It had been a costly effort, the mission to secure the Toktong Pass, but as those Marines struggled down the road to safety, Barber knew it had been worth it.

Despite the presence of Barber and Davis on Toktong Pass, the movement to Hagaru-ri was not easy. For the entire 14 mile mountainous route, the Marines had to fight for every inch of progress. The Chinese weren't content to see the First Marine Division leaving, they wanted to wipe them out to a man. Dressed in the uniforms of friendly forces, one CCF force attacked near a position held by Sergeant James E. Johnson of Company J, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division. Johnson rallied his men to resist the opposing force, then placed himself in a position to provide covering fire for his men. It was obvious that he had stationed himself in a no-man's land from which there could be no rescue. Still, he fired on the enemy as the Marines withdrew, buying them precious time before his own time ran out. With his own life, he purchased "tomorrow" for many Marines.

On Tuesday, December 5th the first units from Hagaru-ri began the dangerous 12-mile journey to Koto-ri. Every step was a battle but the survivors of the Chosin Reservoir fought their way out of the frozen lake none would be sorry to leave behind. Back at Hagaru-ri, a mass grave held the remains of far too many comrades who hadn't "reasoned why", but simply gone where they were told, did what duty demanded, and ultimately given everything they had.

On Tuesday, December 5th the first units from Hagaru-ri began the dangerous 12-mile journey to Koto-ri. Every step was a battle but the survivors of the Chosin Reservoir fought their way out of the frozen lake none would be sorry to leave behind. Back at Hagaru-ri, a mass grave held the remains of far too many comrades who hadn't "reasoned why", but simply gone where they were told, did what duty demanded, and ultimately given everything they had.

By mid-day on December 7th, that last men from Hagaru-ri arrived, nearly 25,000 frozen, starving, wounded, battle-weary Marines and their supporting elements from what was left of the Army's 7th Infantry Division. Over the following days, the dangerous withdrawal continued along with the 53-mile distance from Koto-ri to the port at Hungnam.

In a final, desperate attempt to crush the First Marine Division, the CCF destroyed a vital bridge over a 1500 foot gorge between Koto-ri and Chinhung-ni ten miles away. In one of the engineering marvels of modern warfare, the US Air Force dropped eight spans of M2 prefabricated bridge. The two-ton, bulky structures were erected and on December 9th the first soldiers crossed the bridge to safety, followed by thousands more. On December 11th the last American troops arrived in Hungnam for evacuation.

Despite their best efforts, the Chinese forces had failed to crush the indomitable First Marine Division. They came out unashamed, bringing their equipment, their wounded, and most of their dead. They would live to fight another day and continue the gallant legacy of the United States Marine Corps. At the Chosin Reservoir, they established their own legacy, not one of retreat, but one of surviving against incredible odds through leadership, teamwork, and the highest degree of brotherhood.

There were many acts of heroism by thousands of soldiers and Marines at the Chosin that went unheralded simply because they were unseen or unreported. Twelve soldiers, Marines, and one Naval Aviator received Medals of Honor, seven of them surviving to wear their award. All would be quick to point out that the award they wear, they do so in honor and memory of the valiant men whose awards went unrecognized.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED