David R. Kingsley

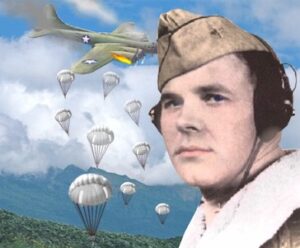

David R. Kingsley

The story of Second Lieutenant David Richard Kingsley is largely forgotten, save for two surviving sisters in his home state of Oregon, his surviving crewmates, and a handful of aging villagers in Bulgaria who witnessed his actions.

B-17 Flying Fortress

Lieutenant Edwin Andy Anderson’s Crew

Air Force Pilot Second Lieutenant Edwin O. Andy Anderson was a strapping young man from Minneapolis, Minnesota. In the fall of 1943, nine young men were assigned to his leadership to crew a B-17 Flying Fortress. In Florida, these ten airmen began the process of working and training together that would enable them to complete future missions, and hopefully survive to return home together. Anderson’s crew included:

• Co-Pilot – First Lieutenant George L. Voss of Chicago, Illinois

• Navigator – Second Lieutenant Robert L. Newson of West Chicago, Illinois

• Bombardier – Second Lieutenant David R. Kingsley of Portland, Oregon

• Flight Engineer/Top Turret Gunner – Technical Sergeant John D. Meyer, Jr. of Queens, New York

• Radio Operator – Don McGillivray of Des Moines, Iowa

• Left Waist Gunner – Staff Sergeant Martin Hettinga of Anchorage, Alaska

• Right Waist Gunner – Staff Sergeant Harold D. James of Chicago, Illinois

• Ball Turret Gunner – Staff Sergeant Stanley J. Kmiec of Hamtramck, Michigan

• Tail gunner – Staff Sergeant Michael J. Sullivan of Villa Park, Illinois

The crew’s bombardier hailed from Oregon, one of two westerners in the team. He was a young man who had already endured much and proven himself strong and dedicated. Since the age of 10, his eight brothers and sisters had relied on that strength to keep the family together. Despite failing health, his mother had always reminded her children, “Love each other, take care of each other.” It was a lesson that young man was to remember now as he becomes part of a new family of ten. Tail gunner Mike Sullivan recalled he was “A friendly, calm, hardworking part of the crew (who) never pulled rank on the noncoms. He had a quiet sense of humor that put everyone at ease.”

In the sky over Europe that 25-year-old bombardier would again demonstrate his love and concern for others, becoming one of World War II’s greatest heroes.

Lt. David R. Kingsley

by Phyllis Kingsley Rolison

Long before Dave was a hero to so many people, he was a hero to our little family. We grew up in Portland, Oregon, at 24 SW Montgomery Street. There were nine of us; five boys and four girls. Dave was next to the oldest; I was next to the youngest. My little sister, Sister Margaret Mary Kingsley, is the youngest. Our father was a special investigator for the Portland Police Department. Before he worked for the police department, he had 8 children and he didn’t have a job. One day he was coming out of church and a man stopped him and said, “I understand you need a job.” He had never seen the man before. He said to go right down to the police department and there will be a job for you. The man at the police department said, “How did you know we had an opening? It just opened up.”

When I was 2 and Dave was 10, our father died in an automobile accident. At this time, my mother had eight children and was five months pregnant with her ninth child. She made a decision right then not to give any of us up. This is when Dave first stepped in to help. He was 10 years old at the time. He and Grandma helped mom get through an almost impossible time. Somehow her strong faith helped her to survive the next few years. My first memory is when I was about 7 years old. We did not have much money, but I remember a life full of love and lots and lots of laughter. Dave kept the boys in line and Grandma took care of the girls. We had a very happy life during those years.

The boys went to St. Michael’s school on SW Montgomery Street, and the girls went to St. Mary’s Academy and then Marylhurst. Every morning we would go to Mass and all of us would sit on the front row of St. Michael’s Church. I was told that my dad wired that church.

When I was 10 and Dave was 18, my mother was diagnosed with cancer. A short time later, she was confined to her bed. She could not turn herself from side to side. When he had to be turned, Dave and one of the boys would pick her up and turn her over. Again, she said she would not give any of us up. She had a plan. Now Dave had a bigger job to do. Grandma had died, so it was his job alone. Now at 18, Dave took over the care of all of his brothers and sisters. (Tom, the oldest brother, joined the Navy in order to provide some income to the family.) He was not only our brother now but had the duties of a father. He talked to us, he listened to us, he made us do our chores and, of course, I’m sure he saw that we said our prayers.

My mother was remarkable. I don’t remember her ever raising her voice in anger to us. She had a punishment for everything we would do wrong. She was a very gentle person. Without a word we knew what would happen if we didn’t obey. A few things come to mind. If we didn’t make our bed before we went to school, all the bedding would be off the bed and we couldn’t go out to play until it was made. It was a hard job for little girls. No one had to say a word. If we girls had an argument, we would have to wash the back door, which was a full window. One on one side, one on the other, until we would begin to laugh and the anger was over.

My brothers were all about 6 feet tall, so she had to somehow let them be boys. She had a boxing ring built out in the back yard. Not a fancy boxing ring, just a plain ring. If the boys fought, she had them get the boxing gloves. they would have to go into her bedroom, put the boxing gloves on, then she would lace them up. After that, they could go out and fight it out. The one that won had to carry the other one in and take care of him until he was okay. That was her way of letting big boys be boys. My brother, Dan, was an amateur boxer and Dave was an amateur wrestler.

While mom was in that bed and couldn’t even move, she taught us many valuable lessons. When we came home from school, mom would want us to come sits on her bed and she would talk to each of us about what happened at school, about life, love and our strong faith. She taught us to love each other, take care of each other, and take care of anyone in need.

All during this period, Dave was taking on the small and big jobs of a dad. One time, two of my brothers decided to go down to the railroad yard, hop on a railroad car, and ride it as far as it would go. What they planned to do at the other end, we don’t know. they got in, closed the door, and later fell asleep. The next thing they knew there was a banging on the door. When they opened it, there stood Dave? He told them to get home where they belonged. What they didn’t know was the railroad car wasn’t going anywhere. It was parked on the side track. Now, my oldest sister was very beautiful. She had boys over all the time. The boys had to pass inspection by Dave. I remember one boy he took aside. What he said and did we never know, but we never saw that boy again. These were some of a father’s duties that Dave took over at the age of 18.

Mom died when I was 13 and Dave was 21 (1939). They put each of us in places where we would be taken care of. I remember Dave coming so very often in his old jalopy to take us for rides, to talk to us, and to see if we needed anything. He was still trying to take care of us.

He was our hero.

While young David Kingsley continued to give his best efforts to keep the communications open among his seven siblings, he went to work as a Portland fire fighter to further support the family. On December 7, 1941, his older brother Tom was serving as a Pharmacist’s Mate aboard the U.S.S. Phoenix at Pearl Harbor. At anchor near the hospital ship U.S.S. Solace when the attack began, the light cruiser returned fire throughout the engagement, escaping damage or casualties.

The following April David left the fire department to join the Army Air Force. His brother Donald joined the Merchant Marines, becoming something of a hero himself. At sea near South America, Donald Kingsley saw a man fall overboard near the bow of the ship and promptly threw a rope ladder over the rail. He then grabbed the ladder and jumped overboard, only to find that the ladder was too short. Instead of hitting the water the rope jerked taught, breaking both of Donald’s arms. Despite this painful injury, Donald yelled for help, then grabbed the drowning sailor and managed to cling to him until assistance materialized. But for Donald’s courageous actions, the other sailor would have floated to the back of the ship where he would have been churned to death by the propeller.

Bob, the youngest of the Kingsley brothers, later joined the Navy and served during the war as a Naval Pharmacist’s Mate. Eugene Kingsley went to work for Douglas Aircraft, building the airplanes that took the war to the enemy.

While in the Army aviation cadet program David attempted to become a pilot but failed the training. He went on to pass the preliminary bombardier-navigator course at Santa Anna, California in April 1943. In July he received his commission as a Second Lieutenant at Kirtland Field in Albuquerque, New Mexico, along with his Bombardier Wings. Brother Tom, who had survived the Pearl Harbor attack, flew in for the ceremony. While admiring his older brother’s colorful array of ribbons David remarked, “If there’s going to be a hero in this family, you’ll be the one.”

David Kingsley and his nine new brothers trained for six months to develop confidence in each other, and to learn how to apply their own specialized training to the fulfillment of their missions. Generally, Army Air Force policy was to assign ten men to a crew, then to keep that crew together from the training phase to deployment. Save for losses due to combat or other circumstances, an aircrew would complete their subsequent combat missions together and then return home as a group. For most airmen, assignment to a crew became a familial adoption process that would become a lifetime relationship.

During the fall and winter as Andy Anderson and Lieutenant Voss flew practice missions with their new crew, the individual members developed a strong sense of trust in the captains of their ship. A mutual bond, a special form of brotherhood, also developed among the team. The dedication that each man had to the other and to the crew as a whole could not help but remind Lieutenant Kingsley of his mother’s oft-repeated mantra to her children, “Love each other, take care of each other, and take care of anyone in need.”

Throughout the fall and winter, crews in training back in the United States followed news on the war front with great interest. Everyone knew of the early August raid on Ploesti, Rumania, a mission that had decimated five B-24 groups of the 9th Air Force and made that previously unheard-of city infamous. In October “Ploesti” was replaced with the name “Schweinfurt”. Sixty Eighth Air Force bombers had been lost in an August 17 raid, then on Black Thursday (October 17, 1943) in a return to Schweinfurt, 65 bombers were lost and 17 destroyed beyond repair. The news slowed through the months of November and December, and well into January and February 1944 as poor weather over Europe caused many bombing missions to be canceled.

Meanwhile in Florida, Lieutenant Anderson’s crew had finished their training. In March 1944 the crew was dispatched to Savannah, Georgia, where they boarded a brand-new B-17 Flying Fortress. For a week the factory-fresh bomber was put through trial runs and then flown to Palm Beach. From there the ten airmen flew south to Trinidad, on to Brazil, continuing across the South Atlantic to West Africa, and finally to Tunis, Tunisia.

Lieutenant Anderson and crew were subsequently assigned to the Fifteenth Air Force’s 341st Bomb Squadron, 97th Bomb Group (Heavy) based at Amendola, Italy. The crew’s flight across the Mediterranean was the last they saw of their new Flying Fortress. Shortly after landing in Italy, their B-17 was absorbed into the inventory of other squadrons, while Anderson’s aircrew went through a few weeks of in-theater training.

As quickly as that training was complete Andy Anderson and his aircrew began flying combat. It was a busy time for the Fifteenth Air Force, and every bomber and crew were a vital part of accomplishing its mission. From April to mid-June the ten men under Lieutenant Anderson were kept busy. Over a period of sixty days, they flew twenty combat missions.

From April 2 to mid-June more than 25,000 Fifteenth Air Force B-17s and B24s flew missions on nearly sixty days. On May 11 the Fifteenth reached its projected strength of 21 heavy bomb groups and mounted a 730-bomber mission the following morning. It was the largest formation thus far fielded. Targets varied; in mid-May, the break out from Anzio required heavy bombardment throughout northern Italy. During this period, however, the Fifteenth also returned again and again to the Weiner-Neustadt aircraft production facilities in Hungary, as well as industrial targets at Budapest, Hungary, and Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Harbor installations and ports throughout the area were struck again and again, heavy bombers hitting as far west as Toulon in Southern France.

From April 2 to mid-June more than 25,000 Fifteenth Air Force B-17s and B24s flew missions on nearly sixty days. On May 11 the Fifteenth reached its projected strength of 21 heavy bomb groups and mounted a 730-bomber mission the following morning. It was the largest formation thus far fielded. Targets varied; in mid-May, the break out from Anzio required heavy bombardment throughout northern Italy. During this period, however, the Fifteenth also returned again and again to the Weiner-Neustadt aircraft production facilities in Hungary, as well as industrial targets at Budapest, Hungary, and Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Harbor installations and ports throughout the area were struck again and again, heavy bombers hitting as far west as Toulon in Southern France.

Fifteenth Air Force support was critical to the success Operation Strangle attained in support of the ground war in Italy. Simultaneously, German aircraft production suffered dramatically and more than 1,000 enemy fighters were shot down by aerial gunners in U.S. heavy bombers and by escorting P-38 and P-51 fighter pilots from April to mid-June. Therein were accomplished on a daily basis, two of the basic missions previously outlined for the Fifteenth. Additionally, General Doolittle, and subsequently General Twining, had been instructed to attack Axis petroleum supplies and to do all that they could to weaken German control in the Balkans. By the end of April 1944 Russian Forces had pushed the Eastern Front steadily backward into Poland in the North and to the northeast border of Rumania in the south. During this same ten-week period more than a dozen, missions were flown against petroleum production at Bucharest, Giurgiu, and the now infamous city of Ploesti.

Ploesti: The Widow Maker

Ploesti, Rumania, was historic decades before World War II made the city of 100,000 at the foot of the Transylvanian Alps infamous. As early as 1857 refineries in the oil-rich region became the first in the world to refine petroleum. The evolving worldwide need for Ploesti’s liquid gold elevated that product to become fully 40% of Rumania’s exports and gave the citizens of the hard-working city a comfortable lifestyle.

During World War I Rumania aligned itself with the Allies. For the first time in history, warfare had become truly mechanical with the advent of cars, trucks, tanks, and aircraft. This new need for fuel, further escalated by the transition of ships from coal to diesel, prompted Germany to invade Rumania in 1916. To prevent Rumanian oil from falling into enemy hands, British engineers already working in Ploesti promptly dynamited the refineries. The damage was so severe it was several years after the end of the First World War before the city returned to its pre-war levels of production.

Two decades later when Hitler began his blitzkrieg in Europe the nation of Romania found itself precariously perched between German advances in Poland and Hungary and Soviet advances from Ukraine. The small country, not even as large as the state of Oregon, found itself besieged on two fronts despite attempts at neutrality.

In June 1941 Rumania abandoned neutrality and joined the Axis, primarily in hopes of regaining areas ceded under pressure to Hungaria and Russia in 1940. Under the protection of Nazi troops, by 1942 Ploesti was producing nearly a million tons of oil a month, including 90-octane aviation fuel, the bulk of it to fuel the Axis war effort. Nearly a third of the fuel needed to field Hitler’s tanks, battleships, and aircraft, came from the refineries at Ploesti.

Ploesti’s location in Rumania made it an unlikely target for Allied bombardment in 1942, but Brigadier General Alfred Gerstenberg, Commanding General and Commander of the Luftwaffe in Rumania knew that sooner or later Ploesti’s refineries would be attacked. Toward that end, he began erecting defenses in February 1942.

In fact, the first attack on Ploesti came far earlier than either the Germans or the Allies could have anticipated. In May 1942 a group of twenty-three B-24 bombers under the command of Colonel Halvor “Hurry-up Harry” Halvorson was dispatched via the South Atlantic to stations in China. The mission to the Far East was disrupted when the proposed bases were taken by the Japanese, and the Halpro Group found itself stuck in the Middle East with no further orders and no place to go.

Unlike later, highly-planned bombing missions over Ploesti, the refineries were more of a target of opportunity for the Halpro mission. It wasn’t until June 5, 1942, that the United States would expand its six-month-old declaration of war to include Hungary, Bulgaria, and Rumania. Sharing the runway at the Royal Air Force airfield in Fayid, Egypt, Colonel Halvorson’s B-24s, at last, had a viable target.

At ten-thirty on the night of June 11, 1942, thirteen of Halvorson’s heavy bombers took off and headed north. As a night flight, destined to put the bombers over Ploesti with the first rays of dawn, it was impossible to maintain a flight formation. Each pilot was on his own, navigating through the dark skies over the Mediterranean while hoping to find his comrades when the morning sun rose over the Black Sea.

One of the bombers was forced to turn back to Egypt when frozen fuel transfer lines cut power to three engines. The remaining twelve continued on towards Ploesti where they dropped their bombs from 30,000 feet on what was believed to be the large Astra Romana refinery. The first raid on Ploesti was unremarkable and inflicted only minimal damage to the Rumanian refineries and German oil supply. Of the twelve Liberators that reached Ploesti, six landed safely in Iraq (the designated recovery point for the mission) and two landed in Syria. Four bombers were forced to land in Turkey where the aircraft were seized and the crews interned. The only injuries were minor, and not a single man was lost or killed in action.

The 2,600-mile (round-trip) Halpro mission to Ploesti demonstrated a previously unanticipated range for American heavy bombers. It was a “note on a brick through the window” to General Gerstenberg that Ploesti was vulnerable to attack, and that the refineries were marked by a big Bull’s Eye on the maps of the Army Air Force. Gerstenberg immediately implemented major upgrades to the Ploesti defenses under his command, fully aware that the American Army Air Force would be coming back soon.

The November 1942 Operation Torch put American bombers in North Africa as the Allies quickly gained control of the region. By the summer American bombers based at Benghazi, Libya, were 200 miles closer to Ploesti than had been the original 13 Halpro bombers that had attacked from Egypt. By now as many as 200 Axis fighters were in the vicinity of Ploesti, including four wings (52 planes) of ME-109s at Mizel, twenty miles east of the city. More than 200 big anti-aircraft guns ringed the city limits to protect the refineries, including 88-mm flak guns and 37-mm and 20-mm rapid-fire cannon. Barrage balloons on explosive-laden cables were raised every night, then lowered during the day. They could be quickly elevated again in the event of a daylight attack. Gerstenberg had every reason to believe he was ready for anything. What he got was an air mission he could never have imagined.

Tidal Wave

The Return to Ploesti in 1943 was the most delicately planned and most specifically rehearsed bombing mission in history. It called for nearly 200 B-24 Liberators to make an early morning departure from airfields in Libya, cross the Mediterranean, climb over the Albanian mountains, and attack seven of Ploesti’s major refineries. To add a stunning surprise, the mission was to be a low-level, roof-top attack.

After months of preparations including practice raids on mock-ups of Ploesti in the Libyan desert, Tidal Wave launched on August 1, 1943. The mission fielded 178 Liberators, 163 of which reached Ploesti to fly into a hell previously unseen by any American airman. Approaching the city so low that some of the bombers picked up grass in their bellies, the inbound formation was stunned when innocent-looking haystacks suddenly fell apart to reveal hidden enemy gunners. Colonel Leon Johnson’s Liberators of the 44th Bombardment Group flew into Ploesti from the north, following a railroad track at tree-top level towards their assigned target. Opposite the track and running parallel with Johnson’s formation was the 98th Bombardment Group’s formation led by Colonel John Kane. The innocent-looking train that also traveled south between the two formations was an example of General Gerstenberg’s extreme innovation to protect Hitler’s black gold. In an instant, the walls fell away from the boxcars to reveal flat-beds containing multiple and deadly Nazi anti-aircraft and machine guns. These took deadly tolls on the two bomb groups and, ultimately, both Johnson and Kane would be awarded Medals of Honor for their bravery as they fought their way into Ploesti.

Tidal Wave was destined to be the only low-level bombing mission launched against Ploesti. The intrepid airmen in their B-24s on that fateful day flew into a maelstrom, dropping bombs from altitudes so low that enemy roof-top guns had to be pointed down to engage the American attackers. Five of the seven targeted refineries were hit: one was permanently destroyed, two were shut down for several months, and two were able to remain in service but at a greatly reduced rate of production. In less than half an hour, five daring heavy bomb groups on what was a near-suicide mission, cut Ploesti’s oil production by 35%, from 400,000 metric tons to 262,000 metric tons, for several months.

Tidal Wave was destined to be the only low-level bombing mission launched against Ploesti. The intrepid airmen in their B-24s on that fateful day flew into a maelstrom, dropping bombs from altitudes so low that enemy roof-top guns had to be pointed down to engage the American attackers. Five of the seven targeted refineries were hit: one was permanently destroyed, two were shut down for several months, and two were able to remain in service but at a greatly reduced rate of production. In less than half an hour, five daring heavy bomb groups on what was a near-suicide mission, cut Ploesti’s oil production by 35%, from 400,000 metric tons to 262,000 metric tons, for several months.

The cost of the mission to the Americans was stunning. Of the 163 Liberators that bombed Ploesti, only 89 returned to Benghazi, Libya. Of those that returned 58 were damaged beyond repair. Of the 1,173 American airmen who flew the mission more than 300 were killed, 200 others were captured and interned as Prisoners of War, and 440 of those who made it home were wounded. Five veterans of the raid were awarded Medals of Honor, more than any other air mission in history, and 56 airmen were awarded Distinguished Service Crosses. More than 800 Distinguished Flying Crosses and Silver Stars were also awarded.

Return to Ploesti

By the Spring of 1944 production at Ploesti had increased to 370,000 metric tons of petroleum products, a commodity critical especially on the Eastern Front. Nazi forces were falling back daily under the Soviet advance, and the disruption of the fuel supply demanded by Axis tanks and aircraft could only inure to a swift Allied victory in the Balkans.

The Fifteenth Air Force’s move to Foggia, Italy, had placed American heavy bombers well within the range of Ploesti. Following the devastating August 1 Tidal Wave mission, however, it would take the U.S. Army Air Force eight months to mount a return. In that interim General Gerstenberg worked around the clock to prepare for the subsequent attacks he knew must come.

Ploesti itself was a city that covered an area of approximately 19 square miles. Twelve major refineries encircled the city, connected by a looping rail system. A rail line south of the city connected Ploesti to the Rumanian capital of Bucharest, 35 miles southward, the site of a major marshaling yard. Pipelines funneled fuel south as well, making its way beyond Bucharest to the port of Giurgiu on the Danube where petroleum was shipped out and needed supplies came in. In the Spring of 1944, all three cities were targeted for attack by heavy bombers of the Fifteenth Air Force.

In the months after Tidal Wave General Gerstenberg had taken dramatic steps to protect Ploesti. It was frequently said that Ploesti was the third-most defended city in the world–behind Berlin and Vienna. Gerstenberg had emplaced nearly 1,000 anti-aircraft guns in a circle around Ploesti measuring 12 miles in diameter. There was no aerial route into the city that was not protected by deadly flak, and any bombers that might make it inside the circle to drop their bombs would then have to fight their way back through more deadly flak. A Confidential 1944 Air Objective Folder prepared by the Army Air Force described Ploesti’s defenses:

The Air Objective Folder made no estimates as to the number of fighters or guns that protected Ploesti, but everyone knew they were significant in number. Furthermore, General Gerstenberg emplaced more than 1,000 smoke pots around the refineries to spew clouds of blinding fog over the city upon initial radar reports of inbound American bombers.

On April 5, 1944, the U.S. Army Air Force, at last, returned to Ploesti; more than 200 Fifteenth Air Force heavy bombers dropped 587 tons of bombs on the marshaling yards. Gerstenberg’s defenses were ready and 13 bombers were shot down by flak or enemy fighters. Ten days later more than 400 heavies returned, more than half the force attacking Ploesti oil production while the remainder simultaneously hit the important marshaling yards at Bucharest. Nearly 800 tons of bombs fell over Ploesti from 290 heavy bombers. Eight never returned home. Nine days later more than 500 heavy bombers repeated the double-punch, and it was obvious to both friend and foe that the battle for Hitler’s black gold had entered a new phase.

Ploesti was hit three times in May: on the 5th, 18th, and on the last day of the month. The mission on May 18 illustrates the difficulties from weather and the dangers from enemy aircraft and guns that plagued nearly all missions into that deadly target. More than 400 heavy bombers were dispatched, including 35 Flying Fortresses from the 463d Bombardment Group. The citation for a subsequent Presidential Unit Citation awarded to that group illustrates the difficulties and dangers well:

“On 18 May 1944, thirty-five B-17 type aircraft, heavily loaded with maximum tonnage, were airborne, and despite adverse weather conditions rallied with the wing formation and set course for their destination (Romano Americano Oil Refinery at Ploesti, Rumania). Under continued adverse weather conditions encountered en route, the visibility became so limited, with dense cloud layers reaching to 30,000-foot elevation, that all other units returned to base. Undaunted by the seemingly overwhelming odds, the 463d Bombardment Group continued on alone through the dense cloud coverage, which rendered compact formation flying extremely hazardous. Despite intense, heavy, and accurate enemy anti-aircraft fire encountered over target, the gallant crews, displaying outstanding courage, professional skill, and determination, though many of their airplanes were damaged severely, maintained their tight formation and brought their ships through the enemy defenses for a highly successful bomb run, inflicting grave damage to vital enemy installations and supplies. Rallying off the target after the bombing run and while unprotected by friendly fighters, the group was savagely attacked by approximately 100 highly aggressive enemy fighters. In the ensuing fierce engagement, while battling their way through the heavy opposition, the group lost 7 bombers; however, in the gallant defense of the formation, the gunners accounted for 28 enemy aircraft destroyed, 30 probably destroyed, and 2 damaged.”

Sandwiched in between Ploesti assignments were other missions like returns to the deadly Weiner-Neustadt Messerschmitt factories, which cost more than 40 bombers downed in two missions in May alone. Ploesti was the target again on June 6 when more than 500 heavy bombers attacked the oil refineries. On June 10 it was the fighters’ turn. Normally the P-38 and P-51 pilots of the Fifteenth’s fighter groups flew escort for the heavy bombers. On this day 1,000-pound bombs were strapped beneath 46 P-38s and, though eight fighters were forced to abort, the remaining 36 successfully dropped bombs on Ploesti oil production facilities. Second Lieutenant Herbert B. Hatch of the 1st Fighter Group flying a P-38 in support of the mission became an ace-in-a-day after shooting down five Rumanian aircraft.

By mid-June Lieutenant Andy Anderson and his aircrew had become seasoned veterans with twenty missions towards the requisite 35 that would earn them a flight home. After flying their first missions in various inventory pool bombers they had at last been assigned their own – a B-17 christened Sand Man. From Sand Man’s cockpit, turrets, and open bomb bay doors they had toured Weiner-Neustadt, Genoa Harbor, Lyon, Nice, Marseilles, and other old-world cities from miles above. Working as a team they had weathered fighter attacks, exploding flak, and the other dangers inherent to aerial combat.

After operating as a team now for more than nine months, they had become uncommonly close, establishing that unique bond of brotherhood shared by men to have endured much and survived. After seventeen missions, with some sadness, the crew had bid farewell to radioman Sergeant Don McGillivray, who was detached and sent to Naples, Italy, for special training on new radar bombing equipment. McGillivray was replaced in Sand Man’s radio room by Technical Sergeant Lloyd E. Kaine, who was quickly accepted as a part of the crew.

Five consecutive days of bad weather grounded the Fifteenth Air Force from June 17 to June 21. The skies cleared enough on the 22d for a 600-bomber mission against targets in Northern Italy. That evening the orders for the next day’s mission were issued. It was to be an all-out attack on Ploesti, the eighth since the bombing had resumed on April 5. It was also to be the largest yet mounted, 761 Flying Fortresses and Liberators assigned to fly through Gerstenberg’s defenses and destroy Rumanian oil.

The roster of pilots from the 97th Bombardment Group assigned to this mission included the name of Lieutenant Edwin O. Anderson. When the sun came up the following morning Andy and his crew would embark on their twenty-first mission. Sand Man had been pulled out for repairs, so the crew would be once again flying in a B-17 from the inventory pool. The crew would also be flying without Lieutenant Voss in the bomber’s right-hand seat. The veteran co-pilot had recently experienced blackouts, and during the five-day period weather had halted operations, he had been grounded for medical evaluation.

“We were wide awake after the predawn briefing where we learned our target for the day: Rumania’s Ploesti Oil Field,” Andy Anderson and other members of his crew wrote in a report to the Kingsley family forty years after their last air mission. “We were confident as our bomber took off about 7:30 a.m. in clear, sunny skies. We had just returned from a rest leave at the Isle of Capri and were ready to get back in action on this, (our) third raid on the strategic Ploesti site. The first Ploesti raid, aided by radio countermeasures (CM) that had fooled enemy gunners, was a good raid with few casualties; prospects were excellent for a repeat. We did not yet know that Axis technicians had cracked the secrets of the new CM, and that many of the planes in our squadron would never return from this raid.”

Opissonya

The level of confidence felt by Anderson’s crew as they took to the skies on the morning of June 23, 1944, didn’t come without considerable frustration. After Lieutenant Anderson attended the 3:30 a.m. briefing, he headed for the airfield to meet with his crew at their assigned plane. With Sand Man down for repairs, the temporary replacement assigned to them was an unknown quantity. Also joining them was Lieutenant William Symons who had been assigned to replace Voss in the co-pilot’s seat for this mission. It was to be Symons’ first combat mission, and none of the crew had met him prior to his arrival on the airstrip.

The level of confidence felt by Anderson’s crew as they took to the skies on the morning of June 23, 1944, didn’t come without considerable frustration. After Lieutenant Anderson attended the 3:30 a.m. briefing, he headed for the airfield to meet with his crew at their assigned plane. With Sand Man down for repairs, the temporary replacement assigned to them was an unknown quantity. Also joining them was Lieutenant William Symons who had been assigned to replace Voss in the co-pilot’s seat for this mission. It was to be Symons’ first combat mission, and none of the crew had met him prior to his arrival on the airstrip.

As other bombers began lining up and warming their engines, Lieutenants Anderson and Symons began their own pre-flight checks. The magnetos on the replacement bomber didn’t check out and Anderson radioed that he would need a different B-17 while the crew began unloading their gear. At 7:00 a.m. other bombers were beginning to take off while Anderson and crew awaited the arrival of their requested aircraft. By the time it arrived and they had stowed their gear and begun pre-flight checks, most of the assigned 97th Bomb Groups Flying Fortresses were already airborne. Taking off late, “we wound up flying tail end Charlie–not the best place to be,” Harold James recalled in a recent phone interview. “Do you know what the name of our replacement plane was?” he continued with a mischievous giggle. “It was ‘Opissonya’!” Then he laughed again.

The mission this day was to be one of the Fifteenth Air Force’s largest to date with 761 heavy bombers (B-24s and B-17s), including Flying Fortresses from all six B-17 groups of the 5th Bomb Wing. Seven groups of fighters were assigned to escort the massive formation protecting the bombers to the target and on the return home. By 8:30 a.m. the aerial armada had formed up over the Adriatic Sea and, flying in a tight formation to maximize their protective firepower, began the nearly three-hour flight to and across Yugoslavia to attack Hitler’s petroleum supply. Anderson’s squadron was to bomb the Dacia Oil Refinery.

“This was our second aircraft of the day and we were flying at the very end of the formation,” Harold James recalled, “Then things got even worse. While we were still over the Adriatic, we blew an oil line on the #1 engine. Andy feathered the engine and then came on the radio to take a vote. Should we turn back or keep on? We usually got double-credit (towards the 35 combat missions required to fulfill a tour) for missions to Ploesti and since Andy figured we could make it on three engines we all voted to continue.”

In the cockpit, Lieutenant Anderson alternated between his duties as a pilot and the normal conversation and orientation that would acquaint his new co-pilot with the job at hand. Lieutenant Symons was well-trained and capable but he still struggled with the mix of emotions every young airman endured upon embarking on his first combat mission. Lieutenant Newson skillfully plotted the course in the Plexiglas nose of the bomber, while nearby Lieutenant Kingsley pondered that he would be celebrating his 26th birthday in four days. Until the bomber reached the IP (Initial Point), the bombardier had little to occupy him. The IP was the point at which the bomber lined up to begin the bombing run; and from that point on the bombardier flew the airplane through a bombsight linked to the autopilot, keeping it straight and level through both flak and fighter attacks, to the release point where he unloaded the bombs.

In the cockpit, Lieutenant Anderson alternated between his duties as a pilot and the normal conversation and orientation that would acquaint his new co-pilot with the job at hand. Lieutenant Symons was well-trained and capable but he still struggled with the mix of emotions every young airman endured upon embarking on his first combat mission. Lieutenant Newson skillfully plotted the course in the Plexiglas nose of the bomber, while nearby Lieutenant Kingsley pondered that he would be celebrating his 26th birthday in four days. Until the bomber reached the IP (Initial Point), the bombardier had little to occupy him. The IP was the point at which the bomber lined up to begin the bombing run; and from that point on the bombardier flew the airplane through a bombsight linked to the autopilot, keeping it straight and level through both flak and fighter attacks, to the release point where he unloaded the bombs.

Throughout the bomber’s fuselage, the six non-commissioned officers went about their own tasks. In the armed Plexiglas top turret behind the cockpit, Flight Engineer Sergeant John Meyer scanned the sky for enemy aircraft. In the radio room, Sergeant Lloyd Kaine performed his own duties while prepared to do double-duty as a gunner if the ship were attacked. Sergeants Martin Hettinga and Harold James manned guns on either side of the bomber’s waist. In the clear ball that hung from the B-17’s belly, Sergeant Stanley Kmiec was prepared to defend against attack from below.

Perhaps the loneliest position in any bomber was the tail, a cramped compartment reached only by crawling through a narrow tunnel from the waist to the rear. Sergeant Michael Sully Sullivan was quite at home in this position. A quiet man, the long hours of flight afforded ample opportunity for personal reflection. It was also far better than standing on the ground dodging flower sacks dropped from bombers overhead.

As incongruous as it sounds, Sully’s first job for the Army had indeed been one of dodging flour sacks. In 1941, before the war began, the young recruit from Chicago was assigned to guard duty at an airfield in Louisiana. It was there that the Army Air Force conducted training exercises and war games for new pilots and aircrews. On the ground Sully ran, dodged, and ducked, as planes flew overhead to drop flower-filled bombs to hone their attack skills. When the war began, he gave up two stripes to enter aerial gunnery school, eventually earning back his stripes and assignment as a gunner in Lieutenant Anderson’s crew that was training in Florida in the fall of 1943. Now, at age 24, he was a seasoned veteran with nearly two dozen combat air missions. Three hours after takeoff, from his position in the tail of Opissionya, Sully watched Yugoslavia’s Albanian Mountains passing behind and knew the formation was over Rumania. From that point on there would not be an idle moment for any member of the crew. Though they had been flying over the enemy territory since leaving the sea, they were now flying into one of the enemy’s most protected lairs.

By 11 a.m. a curtain of flak began to fill the sky in a deadly ring around the Ploesti refineries. Fog from General Gerstenberg’s smoke pots on the ground covered the entire city, and one crewman later said the smoke over Ploesti from both was so thick a man could walk on it. Minutes later the first bombers in the formation broke through the flak-ring to begin their bombing runs. More than forty enemy fighters began to dive on the trailing formations, and from the waist Sergeant’s James and Hettinga watched two Flying Fortresses explode and go down in flames before the enemy fighters broke off. Then Opissonya entered the flak ring and approaching their target.

Suddenly Opissonya was shaken by a horrible explosion, forcing the gunners to struggle for something to steady themselves. The enemy anti-aircraft fire hit the left wing, exploding the Number 1 engine, ripping away a fuel tank, and leaving a 12-inch hole behind the dead engine. Deadly flak continued to pound the bomber, and a second hit on Opissonya’s tail damaged the vertical stabilizer and knocked out the oxygen system. Gunners scrambled for backup oxygen and then returned quickly to their guns. Losing altitude and falling out of formation, Lieutenant Anderson somehow managed to steady the bomber while Lieutenant Kingsley bent intently over his bombsight. Despite the damage, the bucking and jostling of the Fortress as it struggled along on three engines, and despite the continuing thunder of anti-aircraft fire and patter of jagged steel against the bomber, Kingsley managed to unload his bombs on target.

Coming out of the bombing run and struggling out of the deadly flak ring, Anderson fought the controls to remain behind the tight formation that was a bomber’s only source of mutual protection. Losing airspeed, in minutes Opissonya fell more than a vertical mile from 27,000 to 21,000 feet. The crew recalled, “(We) took many hits, and we fought back, scoring two confirmed fighter kills and one probable.” Luftwaffe fighter pilots were quick to spot the vulnerable Flying Fortress trailing the rest of the squadron and immediately pounced. Just beyond the flak-ring, three ME-109s struck at once, knocking out the Number 3 engine. The crew report continued: “The damage was severe; we lagged behind the protection of the tight formation and became a prime unprotected target. Soon, two engines were out one of them on fire. The vertical stabilizer was shot completely away. Waist gunner James noted the control cable from the pilots’ yokes to the tail was hanging limp and useless. The plane faltered and began losing altitude.”

Before American fighters could intervene and chase off the ME-109s, 20-mm. cannon fire hit the tail of Opissonya, shattering Plexiglas and ripping through the protective metal skin. Hot, jagged steel tore into Mike Sullivan’s right arm and shoulder, and additional shrapnel wounded him in the head. With his intercom out and working against intense pain, Sergeant Sullivan began a slow crawl through the tunnel to the waist position, leaving a trail of blood behind. As Sullivan went into shock, James and Hettinga propped him up and tried to stop the flow of blood from his shoulder. Unable to stop the bleeding, they then radioed for the plane’s first aid officer, Lieutenant David Kingsley.

Kingsley pulled Sullivan into the radio room and ripped off his parachute harness to clear the area around the wound. While Kingsley continued to treat Sullivan, in the cockpit Lieutenants Anderson and Newson did their best to head for home. Bad became worse when the number four engine powered down, and limping along on one-and-a-half engines, Opissonya dropped to 14,000 feet by the time the Flying Fortress crossed the border between Rumania and Bulgaria. Under the pilot’s orders, the crew set about throwing out anything that added excess weight in an effort to gain, or at least remains, at altitude.

After the attack that had wounded Sullivan and knocked out the number three engine, two P-51 Mustangs attached themselves as protective escorts for the stricken Flying Fortress. After leaving Rumania behind, and despite the fact that the Axis controlled Bulgaria, it seemed that the worst had passed. The fighter pilots radioed Anderson that they were low on fuel and requested permission to head for home. With no other aircraft, friend or foe, in the area, and with only 500 miles remaining to reach Foggia, Anderson bid them “thank you and farewell.” The bomber pilot could not have known that when Flying Fortress neared Plovdiv, Bulgaria, it would be flying directly over an enemy airfield at nearby Karlovo.

After the attack that had wounded Sullivan and knocked out the number three engine, two P-51 Mustangs attached themselves as protective escorts for the stricken Flying Fortress. After leaving Rumania behind, and despite the fact that the Axis controlled Bulgaria, it seemed that the worst had passed. The fighter pilots radioed Anderson that they were low on fuel and requested permission to head for home. With no other aircraft, friend or foe, in the area, and with only 500 miles remaining to reach Foggia, Anderson bid them “thank you and farewell.” The bomber pilot could not have known that when Flying Fortress neared Plovdiv, Bulgaria, it would be flying directly over an enemy airfield at nearby Karlovo.

Karlovo was a training field for Bulgarian pilots who, in recent months had attacked heavy bombers returning home from missions over Rumania, and occasionally dueled with escorting American fighters. The base was under the command of German Major Helmut Kühle, whose Luftwaffe pilots trained and flew with the Bulgarian 652d Yato (squadron), 6th Iztrebitelen Polk (fighter regiment). Air battles against the new P-51 Mustangs had proved deadly, the squadron losing 9 aircraft with 7 more damaged in one recent engagement. When the two American P-51s headed for home leaving Opissonya alone, Major Kühle immediately fielded eight ME-109s, four flown by his own Luftwaffe pilots and four by the Bulgarians.

With the enemy fighters attacking aggressively out of the sun, Opissonya was suddenly rocked once again by a deadly fire in a running fifteen-minute air battle. Shrapnel from a 20-mm. cannon wounded Sergeant Kmiec, forcing him to leave the ball turret. Lieutenant Kingsley was still working on Sullivan’s wounds and reassuring him that, “It will be okay…we’ll get you out of here,” when Kmiec entered the radio room for treatment to his own wounds. Pilot and co-pilot fought nearly non-existent controls while Newson manned the nose guns, Meyer fought the top turret, and James and Hettinga held their posts at the waist. Opissonya shuddered repeatedly, smoke pouring from both wings as it steadily lost altitude–and still the enemy fighters kept coming.

With all hope gone Lieutenant Anderson lowered his landing gear, an aerial act similar to an infantryman dropping his weapon and raising his hand. The enemy fighters broke off and held their fire, but continued to shadow the floundering bomber. When a pilot lowered his landing gear it was expected that either the crew would bail out or that the bomber would land. Most Luftwaffe pilots respected these terms of surrender and, if the crew didn’t bail out, escorted the bomber to the nearest landing field or clearing. On this day there wasn’t any clearing suitable for landing, and serious doubt remained as to how much longer Opissonya could even remain airborne. Lieutenant Anderson rang the “bail-out” bell.

The communications system among the crew had already been knocked out, so the only word any of the crew had as to their fate was the clamoring sound of the alarm ordering them to get out quickly. At the waist Radioman Kaine and gunners, James and Hettinga quickly checked each other out and then jumped out the waist door. Sergeant Meyer left the top turret and jumped through the open bomb bay, while Lieutenant Newson went out through the bombardier’s escape hatch.

In the radio room Lieutenant Kingsley grabbed Michael Sullivan’s parachute and prepared to strap it on the wounded tail gunner, they then realized that not only were the straps damaged but that the chute itself had been peppered with shrapnel. Without hesitation, Kingsley did something that would haunt Sullivan for the rest of his life. Remembering the words of his mother, David Kingsley took off his own parachute and strapped it on his comrade. “David then took me in his arms and struggled to the bomb bay, where he told me to keep my hand on the ripcord and said to pull it when I was clear of the ship,” Sullivan later recalled. “Then he told me to bail out. I watched the ground go by for a few seconds and then I jumped. I looked at Dave the look he had on his face was firm and solemn. He must have known what was coming because there was no fear in his eyes at all. That was the last time I saw… Dave standing in the bomb bay.”

As quickly as Sullivan was out of the airplane Dave Kingsley stood, just in time to see Lieutenant Symons heading for the bomb bay doors. “Where’s Andy?” Kingsley shouted above the din. Symons pointed toward the cockpit and then dropped into the open sky below, nearly colliding with the pilot who nearly simultaneously bailed out through the bombardier’s escape hatch.

Lieutenant Kingsley, having given up his parachute to a comrade, now remained alone in the rapidly falling bomber.

A Sad Day at Suhozem

Seventeen-year-old Petrov Georgiev watched the air battle from the ground in Suhozem. The small village, with fewer than 200 residents, sits quietly in the farming country amid vineyards and fields surrounded by high wooded hills. From the ground Petrov watched the American bomber take repeated hits, then lower its landing gear. Moments later he counted nine white parachutes billowing beneath the smoking ruin of Opissonya. He had no way of knowing if that was all there was in the foreign bomber–nine men–or if some remained in the doomed airplane.

He watched as one of the Bulgarian fighters made a few passes at the open parachutes, though none of the Luftwaffe or Bulgarian pilots fired on the Americans. “He made a pass at me, and I was afraid he was going to start firing,” Harold James recently recalled. “Instead, I think he was just trying to collapse our chutes.”

Mike Sullivan remembered in a 1984 interview that indeed the pass did cause his own parachute to collapse, “Causing me to go into a free fall that I finally pulled out of. It was my first, and last, jump. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Kingsley was sort of looping the ship. He pulled her out two more times…To me, it looked as if he was trying to crash-land the plane and while all that was going on, the ME-109s were still making passes at it. He knew the basics of how to fly, but the way that plane was shot up and with just one out of four engines under full power and the direction controls all damaged, it would be nearly impossible for one man to handle those controls.”

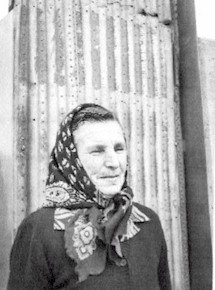

Near the top of the nearby wooded hills that surround Suhozem, Todora Douraliiska and her family were tending the vineyard that might well have appeared to be clearing from the air. Helping out in the vineyard was Douraliiska’s young son Dimitar and infant daughter Lalka. Four other members of the family, Chonna, Mina, Nona, and Denko were helping out when the air battle overhead diverted their attention. The family watched nine parachutes drop from the bomber before it passed over them, and then saw it turn back towards the north heading straight for the vineyard. All started to run but then stopped when they realized 9-month old Lalka had been left behind. They were rushing back to rescue the infant when the worst happened…

Michael Sullivan recalled, “(Opissonya) went into her last dive, corkscrewing nose first toward earth.”

Eight miles away at the Karlovo Airfield Stefan Marinopolski, a Rumanian pilot who had watched the air battle and subsequent crash from his tent on the ground, commandeered a jeep and headed for the site of the crash. He was the first to arrive. “There was a big explosion and a lot of smoke,” he remembered. “Through the fire and smoke, I could see Kingsley’s body in the cockpit. There was nothing I could do for him. And lying nearby was a peasant family–father, mother, and daughter (as well as four other family members). They were probably running away to escape the crashing plane, but it went into them and they all were killed.”

Prisoners of War

While at the crash site Stefan Marinopolski learned that three of the men who had parachuted from Opissonya had been captured and were being held at the local town hall. There was little more that he could do on the hilltop so he rushed back into the village. There he found Sergeant Hettinga, Sergeant Meyer, and the wounded Sergeant Sullivan under guard. Marinopolski put the three men in his jeep and drove the short trip back to the Karlovo Airfield. After assembling his prisoners in the Officer’s Mess tent, he summoned a doctor to treat Sullivan’s wounds.

While at the crash site Stefan Marinopolski learned that three of the men who had parachuted from Opissonya had been captured and were being held at the local town hall. There was little more that he could do on the hilltop so he rushed back into the village. There he found Sergeant Hettinga, Sergeant Meyer, and the wounded Sergeant Sullivan under guard. Marinopolski put the three men in his jeep and drove the short trip back to the Karlovo Airfield. After assembling his prisoners in the Officer’s Mess tent, he summoned a doctor to treat Sullivan’s wounds.

Marinopolski, speaking through an interpreter, told the three prisoners that he had visited the crash site and found one man dead in the cockpit. He produced the wallet he had taken from Kingsley’s body, showing the identification of the man who had given his life for his friends. Already shaken by the traumatic events of the day, confirmation of David’s death only added to their grief, as they wondered about the fate of the other six members of their crew.

A short time later the recently captured Lieutenant Anderson and Sergeant Kmiec were brought into the mess tent to join their comrades. In a kind gesture to fellow airmen who had already endured much and who now feared for their own fates, Martinopolski ordered a brandy for all of them. They were also fed a meal of black bread and beans.

A short time later the recently captured Lieutenant Anderson and Sergeant Kmiec were brought into the mess tent to join their comrades. In a kind gesture to fellow airmen who had already endured much and who now feared for their own fates, Martinopolski ordered a brandy for all of them. They were also fed a meal of black bread and beans.

Martinopolski’s kindness aside he was still an officer in the Bulgarian Air Force, who had flown combat against American Airmen and had suffered major damage to his own fighter in the battle that had sent nine of his comrades down in flames. He now bent to the task of interrogation, a process he conducted in a conversational manner through an interpreter. He asked the captured fliers to identify themselves, and when it came Sergeant Hettinga’s turn the young gunner pulled a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes out of his pocket, removed the inside wrapper, and wrote on it “Martin Hettinga, Vicksburg, Michigan.” Then with a smile, he flippantly conveyed through the interpreter, “Come and see me after the war.”

The Bulgarian officer talked with the men well into the night, during which militia patrols captured Lieutenants Newson and Symons and brought them to Karlova Field. The eight men were then transported to a military camp at what had once been the American college campus in the nearby Bulgarian capital city of Sofia. Four days after the crash the eight men were sent on to the Prisoner of War camp at Choumen.

Unlike other theaters of combat in Europe where prisoner of war camps was so large that officers and enlisted men were sent to separate camps, all eight captured fliers remained together until they were moved to Allied Control in Turkey on September 10, preparatory to their release. During their two-and-a-half months of internment, despite their own deprivations, they could not forget the valiant bombardier who had gone down in the cockpit of Opissonya. They also feared for the fate of the remaining member of the crew, waist gunner Harold James who had bailed out but disappeared into oblivion.

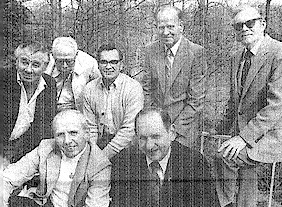

Eight of the nine members of the crew of Opissonya during their captivity in Rumania

Freedom Fighter

The nine men who parachuted from Opissonya landed in the heavily wooded hills scattered miles apart. Sergeant Harold James touched down to find himself alone, and he knew the local militia would soon be out in force to locate the American fliers. He quickly hid his chute, explored his surroundings, and upon finding a cave he hid there throughout the afternoon. At one point local militia indeed passed by him, but the sheltering cave concealed him well enough to avoid capture.

The following day Sergeant James began following a road in his efforts to evade the enemy and walk until he was out of danger. Before darkness fell, however, a Bulgarian patrol captured him and took him to a nearby village where he was placed in the local jail. While behind bars he was informed that a prison truck would arrive the following day to take him away.

He awoke the next day to the sound of gunfire nearby. “My God, they’ve put together a firing squad for me–I’m a goner,” he thought. Sitting alone in fear, the sound of gunfire drew nearer, followed by the incredible commotion as the jail was being torn apart. “A group of rough-looking guys with guns and bandoliers broke into the jail and opened my cell,” he recently recalled.

“They were jabbering at me in Bulgarian, so I didn’t have any idea what they wanted. When they saw I couldn’t understand them, they tried Spanish. When that didn’t work, they started speaking to me in French. Since I was just out of high school and had studied a little French, we were able to communicate a little. They informed me that they were part of the Bulgarian (civilian) resistance and that they wanted me to go with them. I figured I might as well go, rather than wait for the prison truck.”

The band of resistance fighters and their American charge left the village and marched up into the mountains, engaging in a gun battle with the local militia on the way. James began to wonder at his decision, to ponder if he had jumped from the frying pan into the fire. Upon at last reaching the camp he was introduced to the resistance leader who told him in broken English, “You are going to be with us a long time.” The leader summoned a young woman named Stefca, a 21-year-old former school teacher, and told her, “Stay with James.”

“Over the following months she was kind of like my nanny,” James recalled. She taught James some of the language, helped him to understand the resistance movement, and interpreted for him when he needed to communicate with others. In the weeks that followed the freedom fighters made several raids into Bulgarian villages, cutting communications and robbing militia storehouses for supplies. Sergeant James often accompanied them on these, several of which involved gun battles. “Gee, I’m gonna get myself knocked off this way,” he said to himself. “So, by September I convinced the resistance leader that I would be more valuable to him if he could help me get out of there–get to Allied lines–where I could talk to someone higher up and get supplies sent back in by parachute.”

Before James could be secreted out, however, October came, and with it arrived the advancing Soviet forces. Quickly the Nazi forces drew back, and Rumania fell to Russian control. “The Russians told me I had to leave or else–and I had a pretty good idea what ‘or else’ meant,” James recalls. Two majors flew up from Istanbul to visit me and in October I went back with them to Turkey.

By September 1944, Turkey had become the staging point for the return of Allied prisoners of war held in the Balkans. James’ eight crewmates arrived in Turkey on September 10, and by the end of the month, seven had been flown back to Italy. Only Michael Sullivan remained in Turkey when Harold James arrived, and when the two met it was an exuberant and surprising reunion. Sully and the other seven men who had been held at Choumen had heard no word of James’ fate and worried for his life.

Together Sully and James were flown to Cairo, Egypt, in October. “They de-loused us, checked us out and cleaned us up, and put us up in the Shepherd Hotel–which was wonderful,” James recalls. “Then the Red Cross took us on a tour to see the pyramids and the Sphynx. We were flown to Fifteenth Air Force Headquarters at Bari, Italy, and finally caught a flight in a B-17 from the 341st Bomb Group back to our squadron. That was the scariest. We had this young, hot-shot pilot who wanted to fly less than 1,000 feet over the sea and it scared the hell out of me. He should have known you don’t fly a B-17 that way.”

Sullivan and James returned home together, arriving in the United States in time for Veterans Day. They were given 21-day furloughs that were extended to 30 days, before returning to service. “We wanted to go back (into combat),” James says. “But the Air Force had this policy–if you had been captured or under enemy control, they kept you stateside.”

By Christmas, the only member of the crew of Opissonya who had not returned to the United States was Lieutenant David Kingsley. After burying their own seven dead the villagers of Suhozem had removed David’s body from the wreckage of the plane and buried him nearby. The people of Suhozem knew little of the American airman, only that he had done something very brave. He would not be quickly forgotten.

From the ground, they had witnessed his sacrifice.

Medal of Honor

On Friday, May 4, 1945, Lieutenant David Richard Kingsley was remembered during funeral services at St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church in Portland. It was the church Kingsley had attended with his parents before their deaths, the church in which David’s sister Phyllis had been sitting when she received the news of her brother’s death.

On Friday, May 4, 1945, Lieutenant David Richard Kingsley was remembered during funeral services at St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church in Portland. It was the church Kingsley had attended with his parents before their deaths, the church in which David’s sister Phyllis had been sitting when she received the news of her brother’s death.

The flag-draped coffin was symbolic; David Kingsley’s body was still buried on a hillside in Rumania. The empty coffin served however as a reminder that the young former firefighter from Portland had paid the ultimate sacrifice in the service of his country.

The funeral for David Kingsley included yet another symbol–a symbol of courage above and beyond the call of duty. Before the flag-draped coffin, Major General Ralph P. Cousins presented Navy Pharmacist’s Mate First Class Thomas Kingsley with his brother’s Medal of Honor. It was one of only two known such presentations ever made in a church. On May 10, the City of Portland issued a Resolution recognizing Kingsley’s heroism and the lessons of his youth that made him a hero. It noted:

The funeral for David Kingsley included yet another symbol–a symbol of courage above and beyond the call of duty. Before the flag-draped coffin, Major General Ralph P. Cousins presented Navy Pharmacist’s Mate First Class Thomas Kingsley with his brother’s Medal of Honor. It was one of only two known such presentations ever made in a church. On May 10, the City of Portland issued a Resolution recognizing Kingsley’s heroism and the lessons of his youth that made him a hero. It noted:

“The act of Lieutenant Kingsley was one of deliberately placing his own parachute harness about the body of a seriously wounded tail gunner thereby making it possible for the wounded man to reach safety but removing all possibility of saving his own life in the impending crash. His act which showed inherent desire to save the life of another undoubtedly was attributable to Lieutenant Kingsley’s training in the church and his training while a member of the City of Portland, Bureau of Fire.”

Forty-four years after David Kingsley’s death his youngest sister Margaret, a Holy Names Nun at Marylhurst, said, “(David) showed no qualities on that plane he hadn’t already shown as a young man. David Kingsley didn’t need death and a medal to become a hero. If love, selflessness, and devotion to duty are the standard, (David) already was one.”

Phyllis Kingsley Rolison, the only other of David’s siblings still alive said, “We are so proud of Dave for sacrificing his life for his fellow crew members. I must tell you, though, we were not surprised that he would give his life to save another. He spent his short life–26 years–helping others. Dave learned my mom’s lesson well:

“Love each other, take care of each other, and take care of anyone in need.”

Anchorage, Alaska

January 1982

Martin Hettinga picked up the receiver of his telephone when he heard it ring, wondering who might be calling. In broken English, the voice on the other end asked if he was speaking to Martin Hettinga, a World War II airman who had been shot down over Bulgaria.

Thirty-eight years had passed since that fateful day, and the nine members of the crew who have returned home had tried to get on with their lives and forget the horrors of war. Some had stayed in touch, but time and movement had distributed them across the nation, and few among them knew where to look to find the others. Though the voice on the other end, due to the strange accent, couldn’t be one of Hettinga’s crewmates, he, at last, replied that the caller had found the right man.

“Do you remember writing your name and city on a cigarette wrapper and saying, “Come visit me after the war’,” the caller continued? Martin stammered briefly and then acknowledged the incident. “Well, I’m here and I want to come and visit you,” replied Stefan Marinopolski, the man who had personally captured Hettinga and two of his comrades after they bailed out.

After the Russians took Bulgaria in October 1944, Bulgarian officers that had previously fought with the Nazis were subjected to considerable suspicion, despite a quick alliance between the Bulgarian government and the Soviet Union. A post-war, May 25, 1946, incident in which two Bulgarian pilots defected to Italy to request asylum brought even more pressure on Marinopolski, who was suspected of complicity in their defection.

Subsequently, Marinopolski was arrested and, without a trial, was sent to a labor camp near Pernik, Bulgaria, for more than a year. He was released to live now devoid of the prestige and respect he had previously enjoyed as a Bulgarian Air Officer, searching desperately for any kind of work until he was arrested again in 1950 as “an enemy of the people.” Again, without a trial, he was held for two years, after which he worked in construction while plotting to escape.

In 1957, Marinopolski was sent to Czechoslovakia under a work exchange program. On December 1, 1957, he escaped to Austria where he spent four months in a refugee camp. By 1959 the former Bulgarian Squadron Leader was working for Radio Free Europe. That job eventually netted him a work permit and clearance to come to the United States, where he settled into the construction business in Arlington, Virginia, in 1964.

Never far from Marinopolski’s mind was the air crash of June 23, 1944. Often, he thought of the eight men who had bailed out and been taken, prisoner. His searches of the directory for residents of Vicksburg, Michigan, failed to turn up the man who had written his name and hometown on a cigarette wrapper, but Marinopolski kept looking. At last, he located a relative of Hegginga’s in Kalamazoo, Michigan, who provided Martin’s phone number in Alaska.

In October 1983, Stefan Marinopolski flew to Alaska where he and Martin met for the first time in 39 years. It was an emotional reunion, filled with news and questions. Stefan asked about the other members of the crew, but Martin had lost touch with them through his moves.

It was one year before the fortieth anniversary of that fateful mission that had drawn two former enemy airmen together. With the help of William H. Fleming, III, a staff member on the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Aviation, a search was launched for the remaining members of the crew, as well as surviving members of David Kingsley’s family.

After much hard work, the surviving members of the crew were located, including Michael Sullivan, to whom David Kingsley had given his parachute. Sullivan had spent years trying to put the war behind him. “He remained a confirmed bachelor until age 36,” Gloria Sullivan recently remembered in a phone conversation about her late husband. “When we married, he never talked about the war or what he had done. I had a picture of him in uniform, but that is all I ever knew about what had happened until the reunion. One thing I do remember is that, despite the fact I didn’t know about the mission, Mike always made sure we went to church around the 23rd of June. Ironically, without ever knowing about the crash or David Kingsley, both of our daughters married young men named ‘David’.”

On Easter Weekend 1984 a tearful reunion that included members of Kingsley’s family was held in Washington, D.C. On April 22 the crew wrote and signed a report of the events of that fateful day forty years earlier, noting:

“This is our report to you, the family of David Kingsley, who richly deserved his Medal of Honor. Our friend, Dave, would have done the same for any of us that day had we been wounded. We honor his spirit today, and give you this account, 40 years later.”

The following day the reunited airmen traveled to Arlington National Cemetery where Lieutenant David Kingsley had been re-interred years earlier after the discovery of his grave in Bulgaria. Gloria recalled the emotion of that difficult day as the survivors remembered a friend and comrade. “Standing at David’s grave, Mike’s eyes filled with tears and then he began to shake all over. Looking at the grave he shook his head and muttered,

“‘It shouldn’t have been you–It should have been me!’

“Then Mike went into shock and the guys helped me take him back to the car. It was hours before he at last began to come back around. When I remember that day, I think to myself, ‘If it wouldn’t have been for David, I wouldn’t have met the man I was married to for forty-seven-and-a-half years.”

Before the survivors of Andy Anderson’s crew left Washington, eight of them recreated a photograph that was taken nearly forty years earlier when they had been prisoners of war.

In the aftermath of World War II, life continued as it had for centuries in the quiet Belgian village of Suhozem. Families tended their flocks and their crops, eking out a living from the land and doing their best to remain inconspicuous under the harsh post-war rule of the Soviet Union. Unforgotten were the seven members of the Douraliiska family or even the foreign airman who had for a time been buried on a nearby hill. Villagers had retained souvenirs from the crash site.

In the aftermath of World War II, life continued as it had for centuries in the quiet Belgian village of Suhozem. Families tended their flocks and their crops, eking out a living from the land and doing their best to remain inconspicuous under the harsh post-war rule of the Soviet Union. Unforgotten were the seven members of the Douraliiska family or even the foreign airman who had for a time been buried on a nearby hill. Villagers had retained souvenirs from the crash site.

Among those souvenirs was a six-foot section of Opissonya’s wing, recovered by Maria Douraliiska, a relative of the seven villagers killed when the bomber crashed. For decades Maria had used the largest remnant of the American bomber to dry apples, plums, pears, and wool. It had served her well as it was long, flat, and retained heat in the sunshine.

During World War II the Bulgarian people had allied with Germany out of fear of Russia. Survival depended on having at least one strong ally. During the war, though Rumanian and Bulgarian forces fought with the Nazis on the Russian front, there was little animosity towards the United States. This contributed largely to the strong partisan freedom fighters’ movement, and generally good treatment of Americans captured. Following the war, Bulgaria found itself under Soviet domination and therefore still at odds with the West.

On November 10, 1989, after decades under Soviet rule, Todor Zhivkov resigned his positions as head of the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) and head of the state of Bulgaria. One year later Bulgaria had at least some of the primary building blocks for a democratic state: a freely elected parliament, a coalition cabinet, independent newspapers, and vigorous, independent trade unions. This also opened the door for a warming of relations with the West.

In 2001 two American pilots serving in Bulgaria as part of a multi-national training force became aware of the crash site at Suhozem. After further research, they learned the name of the American killed in the crash and were surprised to learn that he had been posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor and that an airbase in Klamath Falls, Oregon, had been named for him. Shortly thereafter Retired Oregon Air National Guard Brigadier General William Doctor began working with Oregon Guardsman David Funk to erect a memorial at the crash site. During visits to Bulgaria, the two men joined forces with Bulgarian Air Force Major Nickolay Dimov and Vessela Pechava, an architect in Plovdiv.

In October 2004, Phyllis Rolison and her husband Joe joined a contingent of officers from Kingsley Field in Oregon on a flight to Bulgaria. (Not until work had begun on the memorial was the Kingsley family aware of the civilian casualties of the crash.) Upon arrival, Phyllis met the surviving witnesses to the crash and went with Joe to the crash site where she placed flowers while he searched for and found pieces of the bomber.

On October 23, a delegation of dignitaries from both countries united in Suhozem for the dedication of the memorial to David Kingsley and the Douraliiska family. Phyllis Kingsley Rolison was the guest of honor in a group that included eye-witnesses to the crash, members of the Douraliiska family, and even Ivan Petrov Apostlov, a Bulgarian pilot who had pursued Opissonya in a German fighter on that fateful day. When unveiled, the memorial contained the section of wing preserved by Maria Douraliiska, with a relief view cut into stone opposite the wing. One engraved portion bore a photo and tribute to Lieutenant David Kingsley, with another engraved memorial to the Douraliiska family below.

On October 23, a delegation of dignitaries from both countries united in Suhozem for the dedication of the memorial to David Kingsley and the Douraliiska family. Phyllis Kingsley Rolison was the guest of honor in a group that included eye-witnesses to the crash, members of the Douraliiska family, and even Ivan Petrov Apostlov, a Bulgarian pilot who had pursued Opissonya in a German fighter on that fateful day. When unveiled, the memorial contained the section of wing preserved by Maria Douraliiska, with a relief view cut into stone opposite the wing. One engraved portion bore a photo and tribute to Lieutenant David Kingsley, with another engraved memorial to the Douraliiska family below.

As to the event itself, The Oregon Sentinel reported:

“Every aspect of the dedication ceremony involved a mix of American and Bulgarian elements. It opened with the traditional Bulgarian custom of presenting bread and salt to guests. A color guard of American and Bulgarian military personnel placed flags in their stands. Both Bulgarian and American chaplains delivered invocations. A Bulgarian military band played the national anthems of both countries. Bulgarian soldiers placed floral wreaths in front of the memorial. Following speeches by (American Ambassador to Bulgaria James) Pardew and the local Bulgarian officials, a folded American flag was presented to (Phyllis) Rolison, and a bouquet of flowers was presented to Suhozem Mayor Neicho Nedelchev.”

David Kingsley is little remembered outside his home state of Oregon and the small Bulgarian village of Suhozem. Nonetheless, in his valor he gave the gift of life to a friend, in his death he left a legacy of valor and inspiration, and out of that great tragedy of June 23, 1944, two nations have found a new bond of brotherhood.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED