Donald F. Mason

Donald F. Mason

“Sighted Sub – Sank Same”

Shadows of War

In the years of European warfare between 1939 and December 7, 1941, the German U-Boat menace became a deadly noose around the Island nation of Great Britain. So thoroughly was the German blockade prosecuted that Prime Minister Winston Churchill proclaimed it his “greatest worry”. German submarines roamed nearly unmolested, silently stalking convoys of urgently needed supplies making their way to England, and sending tons of shipping to the ocean floor with deadly torpedoes.

Germany and Italy declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, only days after the attack at Pearl Harbor prompted the U.S. Congress to declare war on Japan. Immediately after that German declaration, the United States Congress granted President Roosevelt a declaration of war against Germany and Italy, confronting our nation with a two-front war.

While the early battles in the Pacific dominated the news, and while within a year the American landings in North Africa signaled the opening of that second offensive front, little is often recalled of the battle at home. But World War II was not entirely a war fought on foreign shores. There were of course, the battles fought on American soil at Pearl Harbor, Guam, and even in the Territory of Alaska. But often forgotten is the fact that some of the war’s most costly battles were also fought along the eastern seaboard of the United States.

The first American offensive action against a German submarine occurred as early as April 10, 1941. On that date the U.S.S. Niblack (DD-424) was conducting reconnaissance off the coast of Iceland when the destroyer located three lifeboats containing survivors from a recently torpedoed Dutch freighter. While attempting a rescue, a German submarine was detected and appeared to be moving in to attack. The American commander ordered a depth charge attack, his preemptive actions driving off the enemy sub in what was probably the first clash between American and German forces (excluding the Eagle Squadron pilots who flew during the Battle of Britain) in World War II.

Again, on September 4, 1941, an American destroyer and a German U-Boat engaged each other near Iceland. The U.S.S. Greer successfully evaded two German torpedoes and dropped 19 depth charges, becoming the first American ship to offensively attack German forces in a war that had not yet begun. Following the U.S.S. Greer incident, President Roosevelt ordered all U.S. Naval vessels to attack any ship that threatened American shipping or the shipping of a foreign nation under escort by American ships.

The headline announcing the German attack on the U.S.S. Kearny (DD-432) was more than another detail of war on the American home front. For the United States, World War II had not yet even begun.

On October 16, 1942, the Kearny was one of five American destroyers that raced to the site of German U-Boat attacks on a convoy near Iceland. On the following day, Commander Anthony L. Danis daringly maneuvered his ship to protect the convoy, suffering a direct torpedo hit on the starboard side that killed eleven American sailors and wounded twenty-two. Danis, his Engineering Officer Lieutenant Robert Esslinger, and Chief Machinist’s Mate Aucie McDaniel earned the Navy Cross for their actions to get their wounded vessel safely to port.

On October 16, 1942, the Kearny was one of five American destroyers that raced to the site of German U-Boat attacks on a convoy near Iceland. On the following day, Commander Anthony L. Danis daringly maneuvered his ship to protect the convoy, suffering a direct torpedo hit on the starboard side that killed eleven American sailors and wounded twenty-two. Danis, his Engineering Officer Lieutenant Robert Esslinger, and Chief Machinist’s Mate Aucie McDaniel earned the Navy Cross for their actions to get their wounded vessel safely to port.

Two weeks later the U.S.S. Salinas (AO-19), an oiler based out of Argentia, Newfoundland, was returning to the United States when it was struck by two German torpedoes. Though no Americans were killed in the attack, one sailor was wounded and the ship was badly damaged in the October 30, 1941, incident that earned the ship’s Commanding Officer and four members of his crew the Navy Cross.

The following day while the Salinas was limping for port, the U.S.S. Reuben James (DD-245) was escorting a convoy from Halifax, Nova Scotia when it was attacked by the German U-552 and sunk. Only 44 men of the 159 members of the crew survived, nearly a quarter of the survivors suffering wounds. The Reuben James was the first American ship lost in combat in World War II, and the United States was still not even at war.

The prelude to war should have served as ample warning as to what lay in store once the war was actually declared. Less than a week after war was declared, Adolph Hitler launched Operation Paukenschlag, a direct attack on shipping off the American eastern seaboard. Five German U-Boats departed for American waters between December 18 – 24, 1941, arriving to begin operations by mid-January. On January 11 the U-123 sank the SS Cyclops less than 300 miles east of Cape Cod. Over the following weeks, the Paukenschlag U-Boats scored near-daily victories along the American coast. Twenty-five American ships were lost in 26 days.

Death of a Lady

Reports of the casualties were crushing to the American public, already reeling from the daily bad news coming from the Pacific War. But the bad news on this other front carried with it a unique undercurrent to feed American fears. The ships sinking, planes falling, and soldiers dying in the face of the Japanese offensive were far away. The casualties being suffered to Hitler’s U-Boats were close to home; so close, that the fires of burning and sinking American ships could be seen along the coast at night. An American fisherman who made his living from the sea was now also vulnerable to the enemy when he ventured out to his daily job.

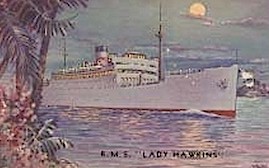

The reality of the danger to civilians became poignantly clear on January 19. Three days earlier the Canadian Steamship “Lady Hawkins” had departed Halifax for Bermuda, stopping at Boston en route to pick up additional passengers. The course was a normal route for the luxury liner that carried primarily civilian tourists, crew, and passengers numbering some 300 on this trip. Among them were 40 young men from St. Joseph, Missouri, who had boarded for passage to promised construction jobs awaiting their arrival in Bermuda.

The reality of the danger to civilians became poignantly clear on January 19. Three days earlier the Canadian Steamship “Lady Hawkins” had departed Halifax for Bermuda, stopping at Boston en route to pick up additional passengers. The course was a normal route for the luxury liner that carried primarily civilian tourists, crew, and passengers numbering some 300 on this trip. Among them were 40 young men from St. Joseph, Missouri, who had boarded for passage to promised construction jobs awaiting their arrival in Bermuda.

With the threat of German U-Boats increasing, the captain hugged the American coast line as far as Cape Hatteras before making his eastward turn towards Bermuda. Shortly after midnight on January 19, the “Lady Hawkins” was briefly illuminated by a bright search light from U-66, and, moments later shuddered under the impact of two torpedoes. Though the ship was only 130 miles from land, most of those aboard her were doomed. Six lifeboats were destroyed by the torpedoes, and only 76 survivors managed to crowd into the only remaining lifeboat, which rated a maximum capacity of 63 persons.

For five days the survivors languished at sea, surviving on a ration of one biscuit, one-quarter of a cup of water, and two teaspoons of condensed milk. Five died during the ordeal before the S.S. Coamo spotted the lifeboat and took the 71 survivors, including a two-year-old girl, aboard on January 24. Only thirteen of the 40 young men from St. Joseph survived, prompting the local newspaper to write,

“May the U-Boat that struck by stealth, bringing death to more than a score of St. Joseph citizens, meet with such a fate.”

The death of the “Lady Hawkins” and the loss of more than 200 civilians only heightened the fear at home in the United States. To make matters worse, the same day that the story of the Canadian ship’s fate reached the press, a Coast Guard ship arrived at Chincoteague, Virginia, bearing eleven survivors of the American merchant ship “Francis E. Powell”. (Seventeen other survivors were also picked up by the tanker “W. C. Fairbanks” and returned to shore in Delaware). The Powell had been en route from Port Arthur, Texas, to Providence, Rhode Island, when it was attacked and sunk on January 27 by U-130. The news gave credibility to the rumors that at least two German submarines were operating in the Gulf of Mexico.

Time magazine subsequently reported that:

“U.S. and Allied ships were being sunk at a disastrous rate, probably equal to the rate at which new ones were being commissioned. Submarines had to be sunk faster than Adolf Hitler could turn them out, complete with trained crews….Off the southeastern coast, a U-Boat slipped in shore and sank two barges and a tug with gunfire. She stood so close by that the barge crews could hear the commands of the officers on her deck.”

World War II had indeed reached the American Home Land!

Ships Sunk by U-66 during Operation Paukenschlag

January 18, 1942 – Allen Jackson (American – 6,635 Tons)

January 19, 1942 – Lady Hawkins (Canadian – 7,988 Tons)

January 22, 1942 – Olympic (Panamanian – 5,335 Tons)

January 24, 1942 – Venore (American – 8,017 Tons)

January 24, 1942 – Empire Gem (British – 8,139 tons)

“Sighted Sub”

Donald Francis Mason was a U.S. Navy pilot with Patrol Squadron Eight-Two (VP-82), stationed at Argentia, Newfoundland. The 28-year old enlisted man was rated Aviation Machinist’s Mate First Class, and piloted a Lockheed “Hudson” PBO-1. The plane carried a crew of three, AMM1c Algia Baldwin as Co-Pilot, AMM2c Albert Zink as Plane Captain, and Radioman Charles Mellinger.

Shortly after 1:00 p.m. on January 28, 1942, Mason and his crew took off for what was a continuing series of anti-submarine patrols over the Atlantic waters that had already become known as “Torpedo Alley”. For two hours the PBO-1 droned over empty waters. As was all too often the case, the long but important patrols were mundane. On this afternoon, however, an unexpected flash of light was spotted on the surface of the dark and rough open waters of the Atlantic. Banking quickly, the crew noticed a periscope protruding above the waves, a distinct wake trailing behind.

Without hesitation, AMM1c Mason launched his attack, bearing in on the enemy submarine that apparently did not realize it had been spotted. The subsequent report filed by Patrol Squadron Eighty-Two Commander W. L. Erdmann vividly explained the combat action in brief but precise terms:

UNITED STATES ATLANTIC FLEET

SUPPORT FORCE

PATROL WING EIGHT

PATROL SQUADRON EIGHTY-TWO

A16-3(02) Argentia Air Detachment

Argentia, Newfoundland

January 30, 1942

From: Commander Patrol Squadron Eighty-Two.

To: Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet.

Via: Official Channels.

Subject: Report of Engagement with Enemy Submarine on January 28, 1942

Plane turned and attacked at once. The submarine was apparently completely surprised, as periscope was visible

throughout entire attack. Approach was made from astern submarine on a course about 20 degrees across

submarine’s course. Bombs were released at estimated altitude of 25 feet, indicated air speed 165 knots.

Two bombs were dropped with a spread of about 25 feet.

Plumes of the explosions were seen to spread, one on either side of periscope, estimated distance 10 feet

from wake line and nearly abreast the periscope. The submarine was lifted bodily in the water until most

of the conning tower could be seen. Headway of submarine seemed to be killed at once and she was observed

to sink from sight vertically. Five minutes later, oil began to bubble to the surface and continued for

ten minutes. At this time it was necessary to leave area in order to return to base by dark. Plane landed

at 1628.

Detailed employment of crew during bombing attack was as follows:

(1) Pilot at the controls:

(2) Co-pilot in the cockpit alongside the pilot, armed bombs, stood by manual release.

(3) Plane Captain attempted to take photographs of target with F-48 camera during glide

approach and after attack. Pictures of this attack were poor because of greatly reduced

lighting conditions.

(4) Radioman in bow at the Navigator’s Desk, acting as lookout with binoculars.

W. L. Erdmann

On February 9 Vice Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll, Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet forwarded reports of the January 28 attack on the German submarine to the Navy Department, noting: “In my opinion the pilot of this plane, who sank a submarine almost single handed, should be awarded a decoration of some sort.” It was the kind of good news the people at home desperately needed; the sinking was a sign that Hitler’s U-Boat menace in the Western Hemisphere could be confronted and defeated.

In fact, the Navy did not officially release news of that action until April 1. Then it was brief and to the point:

“In his first success, announced February 26, Ensign Mason was patrolling when he observed the wake of a submarine proceeding submerged at periscope depth. He turned, dove to a low altitude and dropped two depth bombs, straddling the periscope. The conning tower of the submarine bounded clear of the water for a short period then sank. A large patch of oil soon covered the area.”

Security aside, nearly two months earlier TIME magazine published a hint of what little was known of that action, at the time believed to be the first American sinking of an enemy submarine. In the February 9, 1942, edition, TIME reported the tragedy of the “Lady Hawkins” in a story titled “End of a Lady”. The somber report referenced the loss of the “Francis E. Powell” as well, further noting that, “Reports that two Axis submarines are operating in the Gulf of Mexico brought a complete blackout along 100 miles of Texas coast.”

Those anxious Americans who so desperately needed hope to cling to, found it in the closing three sentences of the article, which quoted only from a four word report radioed back to his base by Mason following his encounter in the Atlantic with U-85:

“The success of counter-measures was the Navy’s own secret. Just one hint was allowed to slip through. The Navy released a terse report of one unnamed flyer:

“Sighted sub, sank same.”

For his actions on January 28, 1942, Aviation Machinist’s Mate First Class Mason was promoted to Aviation Chief Machinist’s Mate and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Post-war records ultimately revealed that no German submarine was sank on January 28, 1942. The U-85 was subsequently sunk by the destroyer U.S.S. Roper in a night surface action off the coast of North Carolina on April 14, 1942.

On March 1, 1942, one month before the Navy released its first official report of Mason’s “sinking”, Ensign William Tepuni, a comrade of Mason’s in VP-82, sank U-656. It was subsequently to become the first confirmed sinking of a German submarine by American forces. Though Donald F. Mason lost that distinction in the post-war correction of the records, on March 15 he attacked and destroyed U-503, a victory that was not only confirmed, but that also resulted in his promotion to Ensign and award of a second Distinguished Flying Cross. Members of his crew also received meritorious promotions for “excellent assistance to the pilot in carrying out the two attacks.” (Both Mellinger and Zink were part of the crew once again in the second act, but Mason’s co-pilot was AMM2c Albert Jurca.)

Far more important than anything than any record for being the first, Donald Mason’s brief four-word report was destined to join phrases like “Don’t give up the ship, and “Damn the Torpedoes, full speed ahead” as one of those rare and memorable battle cries that inspired a nation and gave hope when it was most needed.

“Sighted Sub, Sank Same!”

FOOTNOTE:

On 6 May 1944, U.S.S. Buckley (DE-51) encountered U-66 that three years earlier had incensed the people of many nations when it sank the “Lady Hawkins”. In a battle that included hand-to-hand combat, the U-66 was sunk.

Sources:

Boileau, John, “The Lady Boats”, LEGION Magazine, January/February 2006

Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin No. 302 (May 1942)

“End of a Lady”, TIME Magazine, February 9, 1942

“Under the Sea In Ships”, TIME Magazine, April 13, 1942

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED