Harl Pease

Harl Pease

New Hampshire’s Own

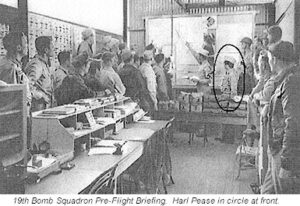

The 19th Bombardment Group (Heavy) began arriving in the Philippines in October 1941 when the first squadron of B-17s was flown to their new duty station at Clark Airfield on Luzon. In November two more flights arrived bringing the Group to a strength of three-dozen bombers and making it the largest 4-engine American bombing force outside the United States. Among the pilots who ferried the bombers to their new airfields in the Pacific was Lieutenant Harl Pease, Jr.

The 24-year-old officer was born and raised in Plymouth, New Hampshire, where his father was a well-known car  dealer and his mother played the organ in the church he had attended in his boyhood. Following high school Pease enrolled at the University of New Hampshire, graduating with a degree in Business Administration in the spring of 1939. On September 29 he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He earned his wings at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas, the following year on June 21. Permanent duty followed with an assignment to the 19th Bombardment Group’s 93rd Squadron at March Field in California.

dealer and his mother played the organ in the church he had attended in his boyhood. Following high school Pease enrolled at the University of New Hampshire, graduating with a degree in Business Administration in the spring of 1939. On September 29 he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He earned his wings at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas, the following year on June 21. Permanent duty followed with an assignment to the 19th Bombardment Group’s 93rd Squadron at March Field in California.

On May 31, 1941, airmen of the 19th Bombardment Group piloted a flight of B-17s from Hamilton Field near San Francisco to Hickam Field in Hawaii. The aircraft made the 2,400-mile flight in 13 hours and 10 minutes. It was the first-ever mass flight of land-based aircraft to an overseas base. For his role in that mission, Lieutenant Pease was awarded the Air Medal.

Throughout the summer the 19th Bombardment Group opened an “aerial highway” across the Pacific, then in October relocated to the Philippine Islands. Lieutenant Pease’s 93rd Squadron was based out of an airfield in the middle of the Del Monte Pineapple Plantation on the southern island of Mindanao, while the other two squadrons operated out of Clark airfield on Luzon.

Throughout the summer the 19th Bombardment Group opened an “aerial highway” across the Pacific, then in October relocated to the Philippine Islands. Lieutenant Pease’s 93rd Squadron was based out of an airfield in the middle of the Del Monte Pineapple Plantation on the southern island of Mindanao, while the other two squadrons operated out of Clark airfield on Luzon.

Within hours of the December 7 attack at Pearl Harbor the 19 bombers at Clark Field were airborne. They returned to the airfield at noon to refuel and arm for a bombing attack against Formosa. Meanwhile, bombers based out of Del Monte were airborne and flying north to provide cover for Clark Field. By the time these arrived over Manila Bay it was too late; eighteen of the nineteen Flying Fortresses based out of Clark were lying in ruin on the ground.

The heroes of the early air war in the Pacific seemed to be found most often in fighter pilots like Lieutenant Boyd Buzz Wagner who became America’s first ace of World War II going man-to-man against Japanese fighter pilots. For the men who flew the lumbering B-17s, the mission assignments may have lacked such glamour, but they were certainly not without equal risk…or valor.

The day after the attack at Clark field the pilots of the 19th Bombardment Squadron began reconnaissance and bombing missions against the Japanese invasion force. Three or four B-17s were put together from the wreckage of multiple bombers at Clark. On December 10 Captain Colin Kelly bombed a Japanese ship steaming with the invading enemy army towards Aparri. Then he valiantly tried to repulse enemy Zeroes on his return flight home. His death and the loss of his bomber only five miles from Clark Field was one more crushing blow to the American Army Air Force in the Far East, but it gave our nation its first air hero of the war.

Four days later a flight of six B-17s was dispatched from Del Monte to attack Japanese invasion forces in the harbor of Legaspi. One of the five was piloted by Captain Hewitt T. Shorty Wheless from Texas. (As a child he had been nicknamed Nun by his classmates because he was so small that there was “scarcely any of him at all.”) It was destined to be the biggest single raid against the Japanese so far in the war, but it was a mission that seemed doomed to failure from the start. The lead bomber piloted by Lieutenant Jim Connally blew a tire during takeoff and was forced to remain behind while his five comrades flew north.

En route Captain Wheless’ B-17 developed engine trouble and fell behind as the formation passed through a storm about 200 miles out of Del Monte. The remaining bombers proceeding to target, but only half-an-hour from Legaspi one of them was forced to turn back due to engine problems. Before the attack commenced the lead bomber under Lieutenant Coats, who had replaced Lieutenant Connally back at Del Monte, was also forced to turn back by a faltering engine. Only two of the original B-17s remained to conduct the mission, each dropping their bombs on a line of enemy transports, then withdrawing through a screen of enemy fighters.

The enemy was now on full alert but that did not deter Captain Wheless, who was still struggling at the controls of his lagging bomber and trying to complete his mission. What happened next was recounted three weeks later in a radio broadcast back in the United States:

January 1941 Radio Address

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

When Captain Wheless managed to nurse his crippled bomber back to Mindanao for a crash landing, ground crews counted more than 1,000 holes in his Flying Fortress. For his courage in completing his mission, then fighting an out-of-control bomber all the way back to Del Monte, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Any bomber that made it home, no matter how badly shot up, was a needed asset. Somehow the ground crews would find a way to patch it up and get it back in the air, or in the worst of cases, at least find serviceable parts for other bombers. On the day that Wheless nursed his own crippled bomber home, the 19th Bombardment Group had only 14 aircraft remaining of its original thirty-five.

The fate of the Philippines was now obvious to all. Japanese troops were landing at the north end of the island and sweeping south. It was only a matter of time before the valiant war being waged by the Philippine Scouts, a few Americans, and some Philippine reservists on the Bataan Peninsula would be crushed. It was equally obvious that the American bomber force could not operate in the enemy-controlled skies around Luzon, and that even the airfield far south at Del Monte was vulnerable. On December 17 those bombers of the 19th Bombardment Group that had survived the first ten days of the war were flown further south to operate out of Batchelor Field, 45 miles south of Darwin in Australia.

Rescuing A General

Back in the Philippine Islands things continued to worsen as the Japanese invasion force overwhelmed the north side of Luzon and pushed south. On January 1, 1942, Manila fell. On the Bataan Peninsula the forces under America’s oldest active-duty general, 59-year-old Jonathan Wainwright, struggled valiantly to stem the onslaught while awaiting the promised reinforcements from the United States. Amazingly they stopped the Japanese advance at the Abucay line and held it for 12 days.

General Wainwright’s boss, General Douglas MacArthur, directed his army from inside the Malinta Tunnel on the fortified island of Corregidor. Meanwhile, plans were underway to slip Philippine President Manuel Quezon out of harm’s way via submarine.

General Wainwright’s boss, General Douglas MacArthur, directed his army from inside the Malinta Tunnel on the fortified island of Corregidor. Meanwhile, plans were underway to slip Philippine President Manuel Quezon out of harm’s way via submarine.

- On January 25 the Japanese invaded the Solomon Islands.

- On February 15 Singapore fell.

- On February 19 Japanese aircraft attacked Darwin, Australia.

Three days later the U.S. submarine Swordfish prepared to take President Quezon and his family out of the now-endangered Island of Luzon, to San Jose on the island of Panay. General MacArthur loaded some of his own family’s personal possessions in the hold of the sub in a footlocker addressed to the Riggs National Bank of Washington. His instructions were that it should be held until claimed by his “legal heirs”. The top American general in the Pacific had chosen to remain at Corregidor.

As the popular Philippine President reluctantly boarded the submarine Swordfish for evacuation, he removed his signet ring and placed it on MacArthur’s finger. “When they find your body,” he told his old friend, “I want them to know that you fought for my country.” Remaining on the island with General MacArthur was his wife and 3-year old son.

On the day after President Quezon departed, a cable arrived at Corregidor from Washington, D.C. advising MacArthur to proceed south to Mindanao and then to fly on to Australia. General MacArthur balked. Despite the man’s oft-argued character flaws, Douglas MacArthur was no coward. Indeed, the man had earned six Silver Stars in the First World War and been nominated for (but denied) a Medal of Honor for actions early in the century in Mexico. This ordered departure came from the President himself after he had agreed with Army chief General George C. Marshall that the death or capture of MacArthur on Luzon would be the final straw in a series of bad news reports coming in from the Pacific war.

Unable to refuse to obey an order from the President himself, MacArthur reportedly wrote up a letter of resignation with the intent of becoming a civilian volunteer to the army on Bataan. His Chief of Staff, Major General Richard Sutherland, argued against the concept. He pointed out the closing lines of the President’s cable…that MacArthur was to leave Corregidor for Melbourne “where you will assume command of all United States troops.” MacArthur’s departure was not a retreat, Sutherland pointed out, but the first step in defeating the Japanese. The forces on Luzon were pitifully small in the face of the massive force pushing south under Japanese Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma. MacArthur was NEEDED in Australia in order to build and lead the army that would ultimately drive the enemy out of the Philippine Islands.

In the end, General Sutherland’s logic swayed MacArthur, and he set in motion a plan to extricate himself, his family, and key members of his staff from Luzon. Had he departed the previous day with President Quezon, it would have been a simple matter. The departure now became far more complex.

Back at home, the American media was reporting on events on Luzon. Their stories left no other conclusion than that the Philippine Islands were lost to the enemy. The only unknown element was how long the defenders could delay the inevitable. These same newspapers speculated that General MacArthur would be whisked out of Luzon before the end came. In Japan, the war planners took note of these stories. As had the American President, they realized the psychological blow the death or capture of MacArthur would have on the already battered American psyche. An entire destroyer division was immediately dispatched to prevent MacArthur’s evacuation. In Japan, Tokyo Rose filled the airwaves with her own speculation…that MacArthur would be captured within a month.

The nearest submarine was the Permit which could not reach Corregidor before March 13. MacArthur was running out of time and turned to a most unconventional escape measure.

In the early days of World War II, the Navy’s MTBs (Motor Torpedo Boat later called PT Boats) was an unglamorous duty assignment for any officer who yearned for his own ship. The small 70-foot, plywood speedboats were viewed as courier craft, not fighting vessels. All that changed in the opening days of World War II thanks to a swashbuckling young lieutenant named John Duncan Bulkeley. As commander of MTB Squadron 3 in Manila, Bulkeley had a command that consisted of six boats, each crewed by about a dozen men. From December 8 to March 11 these flimsy crafts became the fighting navy of the Philippine Islands. For his heroism and leadership, Bulkeley would earn the Medal of Honor, the Navy Cross, two Distinguished Service Crosses, and two Silver Stars.

Bulkeley’s MTBs established a solid record of accomplishment in their early defense of the Philippines, which had not gone unnoticed by General MacArthur. By March the Squadron was down to four badly scarred and battle-worn boats, but MacArthur believed they could somehow ferry him safely out to Mindanao. On March 11 MacArthur turned command of the Philippine Forces over to General Wainwright, then boarded Bulkeley’s PT-41 along with his wife and son.

Those who were left behind may not have envied those who were attempting to break out in Bulkeley’s small PT boats. With Japanese planes scouring the area for any sign of an escape attempt, with enemy patrols increased to all-time highs around the islands, and with a destroyer division steaming their direction, many at Corregidor set MacArthur’s chances of escape at fifty-to-one.

The plan called for Bulkeley’s fast-moving PT boats to carefully wend their way through the myriad of small islands that stretched out between Manila Bay and Mindanao, traveling only at night to avoid detection from the air. Once the boats reached Mindanao MacArthur and his party would travel inland to Del Monte Airfield to fly on to Australia. Before departing Corregidor on March 11 MacArthur phoned his air chief, Major General, George Brett in Australia, to order that three B-17 Flying Fortresses be flown to Del Monte Airfield on March 13 to meet him.

The story of MacArthur’s breakout from Corregidor was published before the end of that same year in a book titled, They Were Expendable. This was subsequently made into a 1942 movie starring Robert Montgomery as Lieutenant Bulkeley (called Brickley in the movie) and John Wayne as his second-in-command. After 35 hours of skillful maneuvers throughout 560 miles of enemy-infested waters, Lieutenant Bulkeley arrived at Mindanao on the morning of March 13.

book titled, They Were Expendable. This was subsequently made into a 1942 movie starring Robert Montgomery as Lieutenant Bulkeley (called Brickley in the movie) and John Wayne as his second-in-command. After 35 hours of skillful maneuvers throughout 560 miles of enemy-infested waters, Lieutenant Bulkeley arrived at Mindanao on the morning of March 13.

Lt. Cdr. John Duncan Bulkeley

They Were Expendable

If MacArthur was well pleased with Lieutenant Bulkeley, he was not so happy with General Sharp. Mindanao’s army commander lined the route from the harbor where MacArthur stepped off PT-41 to the airfield at Del Monte with soldiers, advertising the General’s presence to any Japanese pilot flying overhead.

Too Young to Fly

Two days earlier General MacArthur had departed Corregidor in a battered, 70-foot plywood speedboat to traverse more than 500 miles of sometimes open seas, waters controlled by the enemy, and patrolled from the air. Having endured all that, one might have thought the General prepared for anything. He was not, however, prepared for what happened at Del Monte Airfield when he arrived with his entourage to board the B-17s he had requested for the flight to Australia.

The bottom line was that just as Lieutenant Bulkeley’s PT boats were battle-torn and capable of continued missions only through the courage and ingenuity of their crews, the B-17s that were now flying missions out of Batchelor Field in Australia were in equally bad condition. Most were remnants of the 19th Bombardment group that had survived the action at Luzon and relocated to Australia the previous December.

In the interim, they had been flying bombing and reconnaissance missions out of Batchelor Field, thanks to the diligent efforts of the ground crews which patched up the holes and found ways to keep the propellers turning. Since arriving south of Darwin, few of them had made the 1,400-mile flight back to the Philippine Islands. On January 26 an LB-30 and a B-24 had managed to fly into Del Monte to deliver an emergency request for medical supplies. A second such mission was flown on February 3rd.

On March 11 as General MacArthur was boarding PT-41 at Corregidor, three battered but patched up B-17s departed Batchelor Field to fly additional medical supplies to Del Monte. One turned back and another reportedly crashed. The remaining B-17 was piloted by Lieutenant Harl Pease, whose own Flying Fortress was being held together with “baling wire and bubble-gum”.

Under the dim lights that cautiously marked the airfield at night, he came in for a landing, despite the fact that he had no brakes. After a bumpy landing, he offloaded the needed supplies, then boarded several stranded technicians to fly them out of harm’s way and back to Australia. He was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his heroism in completing this dangerous mission, one made all the more hazardous by the lack of brakes and a badly war-damaged bomber.

Two days later Lieutenant Pease was one of three (some accounts say four) B-17s dispatched under orders from General Brett to meet General MacArthur and fly him to Australia. One of these was forced to turn back due to mechanical malfunctions. Captain Henry Godman’s B-17 was unable to complete the flight, crashing in the sea near Mindanao with the loss of two of his crew. (Captain Godman was later awarded the DFC for this mission.) Again, only Harl Pease remained to fly into Del Monte, where General MacArthur waited with his family and staff.

It was then that MacArthur contacted General Brett to demand the “three best planes” available be dispatched to Del Monte immediately. Ironically, these B-17s came from the Navy’s inventory and were part of its task force at Townsville, Australia. On March 14th they were absorbed into the 19th Bombardment Group as the 40th Reconnaissance Squadron. Three days later three of these B-17s departed Townsville to carry supplies to Del Monte. Until they landed none of the pilots or crew were aware, they would be returning with General MacArthur.

Lieutenant Harold Chaffin’s Flying Fortress was forced to return due to mechanical problems, but two of the big bombers managed to land at Del Monte shortly before midnight. Captain Frank Brostrom’s lead aircraft made the trek despite an overheated supercharger. He gulped coffee while the mechanics worked quickly to repair the defect. Overloaded with General MacArthur, his wife, and son, and several key staffers, Brostrom managed to become airborne in the early morning hours to fly to Darwin. Behind him flew the second B-17 piloted Captain Lewis and his crew of seven, including radio-man Dick Graf.

The following day Lieutenant Chaffin’s repaired B-17 managed to reach Del Monte and safely return to Australia with the remainder of MacArthur’s staff. From then on very few Americans made it off the island before the Japanese took control. Two Navy PBYs managed to evacuate about 50 key persons from Corregidor in the early spring, and one aging B-24 affectionately called Old Bucket of Bolts made nocturnal runs into Del Monte prior to its fall.

“There is a limit of human endurance and that limit has long since been passed. Without the prospect of relief, I feel it is my duty to my Country, and to my gallant troops, to end this useless effusion of blood and human sacrifice. With profound regret and continued pride in my gallant troops, I go to meet the Japanese commander.

Goodbye, Mr. President.”

Valor in the South Pacific

Australia was no safe haven when General MacArthur flew there on March 17. Originally his destination was the city of Darwin, but when Lieutenant Brostrom’s B-17 approached with the dawn it was to find Darwin under attack. The flight diverted further south to land at Batchelor Field.

The battle for Australia actually began on January 23 when Japanese troops landed on New Britain Island northeast of New Guinea. The eastern half of New Guinea and nearby New Britain Island were under the administrative rule of Australia. The small garrison near Rabaul at the north end of New Britain was quickly overwhelmed by 5,000 Japanese soldiers under Major General Tomitaro Horii, and within weeks a series of major airfields were established from which the Japanese hoped to control the region and cut off communications between the United States and Australia.

This immediate threat to Australia moved the Pacific war up a notch in the Allied war plans. No longer could turn back Japanese aggression in Asia and the Pacific be treated as secondary to winning the war in Europe. To compound matters, three Australian divisions had been committed to supporting Britain’s war effort in Europe. With the Australian homeland threatened, these were needed back home. Winston Churchill realized if he were to have help from Australia to defeat Hitler, he would have to first assure them that they would be secured from a Japanese invasion.

By mid-April, the Japanese controlled the west end of Dutch New Guinea and had fortified 1,200 miles of coastline along the north end of the large island. The only thing standing in the way of taking complete control of the landmass was the foreboding Owen Stanley Range that split the Papuan Peninsula on the east side of New Guinea. It created a buffer between thousands of Japanese in the north and the Australian defenders in the south. From their airfields, at Lae and Rabaul the Emperor’s troops easily controlled the Solomons and were close to cutting off all communications between Australia and the United States.

of coastline along the north end of the large island. The only thing standing in the way of taking complete control of the landmass was the foreboding Owen Stanley Range that split the Papuan Peninsula on the east side of New Guinea. It created a buffer between thousands of Japanese in the north and the Australian defenders in the south. From their airfields, at Lae and Rabaul the Emperor’s troops easily controlled the Solomons and were close to cutting off all communications between Australia and the United States.

The key to the defense of New Guinea, and therefore by extension Australia, was the important city of Port Moresby. It was here that General MacArthur established his headquarters after departing Luzon. Meanwhile, Allied aircraft including American bombers from the 19th Bombardment Squadron began flying missions out of Batchelor Field south of Darwin, and out of Townsville on Australia’s eastern coastline, to hit Japanese airfields and bases on New Guinea and at Rabaul.

The Japanese strategy for control of the Pacific was based around a three-phase operation designed to accomplish two primary objectives: to complete the destruction of the American Pacific Fleet and to isolate Australia so that it could be quickly and easily taken for the Emperor.

- Phase 1 labeled Operation Mo, called for the invasion of Port Moresby (and Tulagi, the Solomons’ capital to the north of Guadalcanal), enabling the Japanese to build airfields from which they could easily attack Australia.

- Phase 2 called for the capture of an American strategic position the Japanese referred to in their codes as “AF”, along with a nearly simultaneous attack on Alaska’s westernmost Aleutian Islands.

- Phase 3 would follow with the seizing of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa, thereby effectively isolating Australia from any outside assistance.

The Coral Sea

Mo became operational in early May when the Japanese dispatched the 5th Carrier Division which included the large carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, under Vice-Admiral Shigemi Inouye, to the Coral Sea. These and their accompanying battleships served as escorts for two landing forces that were to invade Tulagi and Port Moresby.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 17 was operating northeast of Australia in the Coral Sea. Under the command of Rear Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, Task Force 17 included the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, 67 carrier-launched aircraft, three heavy cruisers, six destroyers, and two fleet tankers. Back at Pearl Harbor, American cryptologists had broken enough of the Japanese code to be forewarned of the planned invasion. Admiral Chester Nimitz immediately sent Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch’s Task Force 11 to reinforce the Yorktown. Based around the carrier USS Lexington, Task Force 11 added 69 airplanes, two heavy cruisers, and six destroyers to the naval presence assigned to turn back the invasion.

On May 4 the operation began with the landing of Japanese troops at Tulagi, just north of the larger  but relatively unknown island of Guadalcanal. Because the Japanese code had been broken, the landing was not unexpected and pilots from the American task forces were sent to meet them. Flying low, bombers from the American aircraft carriers braved enemy fire to turn back the landing. Lieutenant John J. Powers, a dive-bomber pilot from the Lexington, scored a direct hit on a Japanese gunboat and narrowly missed two others. Even so, by nightfall, Tulagi belonged to the Japanese, though the American’s had drawn first blood in the enemy offensive. Admiral Inouye now turned his force west for the all-important invasion of Port Moresby, acutely aware of the American presence in the Coral Sea.

but relatively unknown island of Guadalcanal. Because the Japanese code had been broken, the landing was not unexpected and pilots from the American task forces were sent to meet them. Flying low, bombers from the American aircraft carriers braved enemy fire to turn back the landing. Lieutenant John J. Powers, a dive-bomber pilot from the Lexington, scored a direct hit on a Japanese gunboat and narrowly missed two others. Even so, by nightfall, Tulagi belonged to the Japanese, though the American’s had drawn first blood in the enemy offensive. Admiral Inouye now turned his force west for the all-important invasion of Port Moresby, acutely aware of the American presence in the Coral Sea.

Lieutenant Powers returned to the Lexington elated at his victory and determined to send more enemy ships to the bottom. In order to accomplish that however, the American pilot first had to find Admiral Inouye’s battle group. For two days scout planes sought them out while Japanese scouts vainly tried to locate the American warships. It was a deadly game of hide-and-seek. When at last they found each other, it signaled the opening of what would be called the Battle of the Coral Sea, a historic change in naval warfare. At no time in the two-day engagement did the vessels of either side make ship-to-ship visual contact, or fire directly at each other. The carrier forces battled from afar using only their airborne armament.

On the morning of May 7, the Japanese drew blood before noon when they sank the American destroyer USS Sims (DD-409) and left the oiler Neosho (AO-23) drifting in ruin. The important tanker was south of the American carrier task forces, having been ordered to remain at what Admiral Fletcher hoped would be a safe distance during the battle. The Sims fought bravely against three waves of enemy airplanes before it was ripped in half and sank in less than a minute. Simultaneously, seven enemy bombs struck the Neosho setting it afire and leaving it drifting aimlessly while the Japanese bombers withdrew. Crewmen of the Sims that survived the sinking floated at sea for ten days before they were rescued. Only sixty-eight survived.

The deck of the floundering Neosho was littered with dead and badly burned crewmen as a fire swept through the damaged, but still-afloat, oiler. Below deck survivors struggled to save their ship. Among the rescue crews was Chief Watertender Oscar V. Peterson, badly burned but still valiantly leading his sailors in trying to put out fires in the boiler rooms. A volunteer was needed to close the bulkhead stop valves in order to reduce the pressure that might otherwise cause an internal explosion that would deal a death-knell to the Neosho.

Rather than ask one of his men to perform this dangerous task, and despite his own painful injuries, Peterson did the job himself. He suffered additional painful burns in the process that was ultimately fatal. His sacrifice contributed greatly to the fact that the Neosho remained afloat for four days until it could be found by a rescue destroyer. For his sacrifice, Chief Watertender Peterson was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

While Japanese pilots were attacking the Sims and Neosho, American scout planes were looking for Admiral Inouye’s task force. What they found was the light carrier Shoho. Torpedo and dive bombers were dispatched from Yorktown. Lieutenant John J. Powers circled high above while the torpedo bombers went in first. Normally his dive-bombers would follow to rain destruction from high above. When his turn came, however, Lieutenant Powers dove within 1,000 feet of the enemy carrier to release his payload from a dangerously low level. His courage paid off, scoring a direct hit and inspiring the other American pilots. When their aircraft turned back toward the Lexington at 11:36 a.m., Lieutenant Commander Bob Dixon radioed “Scratch One Flat Top! Dixon to the carrier. Scratch One Flat Top!” It was the best news to come out of the Pacific in months. Though the Shoho had been only a secondary target in the Battle of the Coral Sea, when it sank below the surface of the ocean, American pilots had gained their first major naval victory of the six-month-old war.

When night fell the American Task Force was still frustrated in its search for Admiral Inouye’s invasion force, and deeply saddened by the loss of two American ships. Aboard the Lexington Lieutenant Powers lectured his squadron in anticipation of more combat the following morning. His subsequent Medal of Honor citation noted his words:

Hours later his pilots at last found the enemy task force. From 18,000 feet they could see the large armada below, containing the big aircraft carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku. The sky was filled with enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire when Lieutenant Powers put his Dauntless into a steep dive. Heedless of the explosions around him he focused on the flight deck of the Shokaku, riding his screaming plane ever closer until nothing but her metal deck could be seen through his cockpit window. From only 200 feet he released his bomb, certain there was no chance it would miss from that altitude. His fellow pilots watched in concern and awe as Powers pulled back and tried to come out of the dive. Below him, the bomb he had released crashed through the deck of the Shokaku and erupted in a mighty explosion. It was an eruption so fierce and so close that it engulfed the Dauntless that had initiated it.

While Lieutenant Powers and his pilots were attacking the Shokaku and Zuikaku, Admiral Inouye’s own pilots were locating the American task force. A fierce air battle followed as the enemy dove in waves to strafe, bomb and torpedo the two big American aircraft carriers. Lieutenant (j.g.) William Bill Hall was a Dauntless pilot who had played an important combat role in sinking the Shoho the previous day. Now, though greatly outnumbered, he valiantly fought to turn back the waves that threatened his own ship.

Lieutenant Hall repeatedly counter-attacked the enemy in actions during which three enemy aircraft were shot down. When the enemy bombers retreated, despite his own serious wounds and the fact that his Dauntless was literally shot to pieces, Hall managed to safely land it. He was the only one of four men awarded the Medal of Honor during the Battle of the Coral Sea, to survive to wear it.

The Japanese torpedo planes and dive bombers returned to their own carriers, not only because they had expended all their ordnance, but also because they had inflicted the damage, they had set out to achieve. The Lexington was ablaze from direct torpedo hits and struggling to remain afloat. Yorktown also had been hit by both bombs and torpedoes and was badly damaged.

Late in the afternoon explosions erupted deep within the Lexington, signaling the end of the great aircraft carrier. The crew was ordered to abandon ship and by nightfall, the U.S. Navy had suffered the first total loss of an aircraft carrier in the war.

Late in the afternoon explosions erupted deep within the Lexington, signaling the end of the great aircraft carrier. The crew was ordered to abandon ship and by nightfall, the U.S. Navy had suffered the first total loss of an aircraft carrier in the war.

The Yorktown listed heavily as it tried to limp back to Pearl Harbor, a gaping hole in her flight deck. The great carrier would survive to fight one more important battle only because of the determination of what remained of her valiant crew. Among those who did what was necessary to save their ship was Lieutenant Milton Rickets, a Naval officer from Baltimore, Maryland. Ricketts was the engineering officer working deep within Yorktown when a bomb had crashed through four levels of the ship to explode beneath the hangar deck. Sixty-four men were killed instantly and Lieutenant Ricketts was mortally wounded.

Before he succumbed to his injuries Ricketts found within himself the strength and will to organize a damage control party and beat back the flames that engulfed his compartment. Struggling against extreme pain, he picked up a fire hose and directed it at the worst of the fire, remaining at this position until he collapsed and died.

Statistically, the Japanese won the battle…one American aircraft carrier sunk, another badly damaged. In addition, the destroyer Sims had been sunk and the Neosho was helplessly adrift at sea.

Strategically, however, it was a turning point for the American forces in the Pacific. At the Coral Sea, American pilots sank their first enemy carrier and badly damaged two others. More importantly, because of that damage, the invasion force headed for Port Moresby had to turn back. It was the last time in the course of the entire war that the important port on the southeast side of New Guinea would be threatened by the sea.

Midway

The Battle of Midway is often called the turning point of World War II. It was a desperate gamble proposed by Admiral Yamamoto shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack and then given new credence by the Doolittle raid on Tokyo. To wrest control of the American outpost at the edge of Japanese-controlled waters, the Japanese commander put together a fleet that dwarfed anything seen by either side to that point in the war. Consisting of 8 carriers, 7 battleships, 20 cruisers, 60 destroyers, 15 submarines, and 30 auxiliary ships, the Japanese naval force was further augmented by 16 troop transports.

Because much of the Japanese code had been broken, American war planners knew that something big was happening. The one piece of vital information missing was exactly where the attack would occur. Intercepted enemy communications referred to “AF” as the target. At Pearl Harbor, the cryptologists knew the “A” stood for “American” but had not yet determined what American base the “F” represented. Some strategists believed this indicated an attack on Alaska, which in fact Admiral

Yamamoto was planning in conjunction with his major strike at Midway. Still, others feared it might signal attacks on America’s west coast. Admiral Chester Nimitz was convinced that “AF” stood for Midway, the 2-square-mile atoll that was the only American station between Hawaii and Japan.

To confirm this belief, in mid-May the commanding officer at Midway was told to send a message in the clear advising Command that the distillation plant on the atoll was damaged, and that he had only enough fresh water for 10 days. As expected, the Japanese intercepted the un-coded message and advised their own commanders in a coded message that “AF is short of water”. Midway was now confirmed as the primary target of Yamamoto’s vast armada.

Midway was quickly fortified with hundreds of aircraft from large B-17 bombers to Navy seaplanes. The USS Hornet and USS Enterprise, recently returned from the Tokyo raid, were quickly armed at Pearl Harbor and sent to reinforce Midway. Admiral Yamamoto’s intelligence information erroneously placed these carriers somewhere in the Solomon Islands, so their presence near Midway would offer him a deadly surprise.

The USS Yorktown, limping slowly back to Pearl after the Battle of the Coral Sea, offered yet one more surprise. Yamamoto believed Yorktown had been sunk along with the Lexington. The big ship’s unexpected survival might have been a moot point as it was estimated that it would take 30 days to repair her and return the carrier to fighting condition. Admiral Nimitz ordered the impossible…repairs in three days. Somehow the workers at Pearl got the job done and the Yorktown sailed out of Pearl in time for Admiral Fletcher’s Task Force 17 to join Task Force 16 at a point 300 miles northeast of Midway Atoll on June 2. When all American naval assets were assembled, in addition to the three carriers Admiral Nimitz had 8 cruisers and 14 destroyers. There were no battleships for all that had been sunk or damaged on December 7. What mattered most, however, was that Admiral Nimitz had the element of surprise.

At dawn on June 4, the Japanese carriers launched more than 100 fighters and bombers to attack American positions at Midway. An American PBY spotted the enemy fleet at daybreak and warned all aircraft at the Atoll to get in the air while the ground forces prepared to defend their position. Major Lofton Henderson was soon airborne from Midway with his squadron of Navy bombers, struggling through a wall of Japanese Zeroes to lay his deadly bombs on the carriers below. In minutes fifteen of his twenty-five SBDs (Slow but Deadly) Dauntless bombers were shot down. Major Henderson’s plane was hit and burst into flames as he dove towards the large aircraft carrier Akagi. Realizing he was doomed in his flaming coffin; Major Henderson continued his attack all the way to his death.

Watching from the cockpit of his own SBD was Captain Richard Fleming, a Marine Corps pilot who had survived Pearl Harbor. He had spent the following months flying endless patrols around Midway. Upon seeing the death of his commander, Fleming put his own airplane into dive, screaming through a hail of enemy fire to drop his bomb. It narrowly missed the Akagi’s deck as the frustrated young man pulled out to head back to Midway. Both Fleming and his gunner were wounded and when he landed, the ground crews counted 179 holes in his Dauntless. Despite his wounds and that damage, Fleming was determined to fly again. This time he wouldn’t miss.

Watching from the cockpit of his own SBD was Captain Richard Fleming, a Marine Corps pilot who had survived Pearl Harbor. He had spent the following months flying endless patrols around Midway. Upon seeing the death of his commander, Fleming put his own airplane into dive, screaming through a hail of enemy fire to drop his bomb. It narrowly missed the Akagi’s deck as the frustrated young man pulled out to head back to Midway. Both Fleming and his gunner were wounded and when he landed, the ground crews counted 179 holes in his Dauntless. Despite his wounds and that damage, Fleming was determined to fly again. This time he wouldn’t miss.

Though the opening hours of the historic battle were both unproductive and disastrous for the dive bombers from Midway, before noon aircraft from the Enterprise swooped in from high above. In less than an hour the Japanese carriers Akagi, Soryu, and Akagi were in flames and sinking. The Japanese fleet had been totally unprepared for the snare Admiral Nimitz had laid for them.

The remaining Japanese carrier Hiryu was all that remained to strike a blow against the American fleet. The flat-top managed to send twenty-five bombers and fighters to attack the already battered Yorktown. While these were attempting to finish the job left undone in the Coral Sea, dive-bombers from the Enterprise found and bombed the Hiryu. Seven hours later it sank, while farther away in the distance the crew of the battered Yorktown tried once again to keep their ship afloat. By nightfall, the Japanese had lost four carriers, damaged one American carrier, and failed to take Midway. The loss was humiliating and Admiral Yamamoto ordered his surviving ships to withdraw to Saipan.

Unlike the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Battle of Midway was both a statistical and a strategic American victory. The one tragedy was the loss of Yorktown which was finished off by a Japanese submarine the day after she was bombed by aircraft from the carrier Hiryu. Marine Captain Richard Fleming was the only man to earn the Medal of Honor during the Battle of Midway, and he would be the last Medal of Honor recipient for more than two months. The next would belong to an Army Air Force pilot…the man too young to fly General MacArthur.

5th Air Force

General MacArthur’s experience back at Del Monte Airfield had been the final straw for his air chief, Lieutenant General George Brett. The supreme commander had always been somewhat dubious of the role of airpower, and even less confident in the man who commanded it from Australia. (Similarly, many airmen had a strong distrust of MacArthur, often speculated to have dated back to MacArthur’s role as a judge in the court-martial proceedings against Billy Mitchell.)

Upon arrival in Australia, MacArthur wired Washington that he wanted his air chief relieved, and a new commander sent to organize his air force. While awaiting the arrival of General George C. Kenney, the man Hap Arnold selected to replace Brett, General Kenneth Walker arrived and began a tour of the American Air Forces. A dedicated proponent of the value of strategic bombardment, he spent considerable time visiting with pilots of the 19th Bombardment Squadron at Townsville on Australia’s east coast. From there, as well as from Batchelor field south of Darwin, pilots continued near-daily missions northward against targets on New Guinea, at Rabaul, and in the Solomons.

By the time General Kenny arrived on July 28 to take charge of his new 5th Air Force, some semblance  of structure and order began to take shape. Missions were laid out with a careful view of tactical planning and a sense of purpose. Even General MacArthur developed some degree of a new appreciation for what his airmen could accomplish in support of ground operations. They became vital that same month when reconnaissance flights in the Solomons revealed that the Japanese were constructing a new airfield on an island just south of Tulagi…an island called Guadalcanal.

of structure and order began to take shape. Missions were laid out with a careful view of tactical planning and a sense of purpose. Even General MacArthur developed some degree of a new appreciation for what his airmen could accomplish in support of ground operations. They became vital that same month when reconnaissance flights in the Solomons revealed that the Japanese were constructing a new airfield on an island just south of Tulagi…an island called Guadalcanal.

Hastily a plan was drafted to land American forces on Guadalcanal. That task was assigned to General Alexander Vandegrift, whose 1st Marine Division was scattered throughout the Pacific. It consisted largely of untrained, untested Marines, and Vandegrift initially expected to have six months to prepare his men for combat. The appearance of the airfield on Guadalcanal reduced his time to six weeks. An invasion was scheduled for the night of August 6-7, and would ultimately comprise the first American ground offensive of the war.

To prevent the Japanese from launching air attacks on General Vandegrift’s Marines, General Kenney prepared a large flight of his B-17s to launch a massive early-morning bombing raid on Rabaul. On the day before the invasion, he planned to conduct a diversionary attack against the enemy airbase at Lae in order to draw enemy fighters away from the Guadalcanal landings. Both missions would be flown by pilots of the 19th Bombardment Squadron, which would be staged forward of their airfield at Townsville and fly out of Port Moresby.

Harl Pease, recently promoted to Captain, was assigned the early mission against Lae. Shortly after taking off at 6 a.m., an engine failed, forcing him to turn back. Since there were no facilities to change his faulty engine at Port Moresby, Captain Pease nursed his Flying Fortress over 600 miles of open water to return to Townsville. There he looked around for another bomber. If he couldn’t complete his mission against Lae, he would certainly try to bomb Rabaul. The members of his crew eagerly volunteered to do what was necessary. U.S. Marine lives hung in the balance.

The only bomber remaining at Townsville was a battered B-17 no longer suitable for combat and now used only for training. For this reason, much of the bomber’s armament, as well as the electric fuel-transfer pump, had been robbed for other airplanes. Pease and his crew quickly installed a bomb bay tank and improvised fuel transfer with a hand pump. The process took three hours. Had anyone in command realized the poor condition of that bomber Captain Pease would have never been allowed to take off. No one noticed, however, so Pease and crew flew back to Port Moresby.

After flying all day Captain Pease and his crew arrived and made a night landing at Seven Mile airdrome at Port Moresby near 1 a.m. on August 7. There they managed only three hours rest before the morning mission briefing was to begin.

The B-17s were scheduled to take off in the early morning for the long flight to Rabaul. Almost immediately fate turned against the mission. First, one bomber crashed on takeoff. Then, two more were forced by mechanical problems to return to base. The remaining B-17s flew northward towards their target, Vunakanau Airfield near Rabaul.

Eleven miles from target the incoming American Flying Fortresses were attacked by a large formation of 30 enemy Zeroes. There was no shortage of Japanese aircraft on Rabaul, which boasted an estimated 150 fighters and bombers at Vunakanau alone. For the remainder of the flight into the target, these fighters attacked the bombers while the American gunners fought back. Pease’s crew shot down several before they were over their target and released their bomb load.

With his mission accomplished, Captain Pease turned back towards Port Moresby. Again, enemy fighters attacked in a running battle that lasted nearly half an hour. Pease’s B-17 sustained major damage and began falling behind as the lead bombers ducked into an opportune series of storm clouds for cover. The last that was seen of Captain Pease and his Flying Fortress was the burning bomb bay tank he jettisoned from his doomed airplane.

With his mission accomplished, Captain Pease turned back towards Port Moresby. Again, enemy fighters attacked in a running battle that lasted nearly half an hour. Pease’s B-17 sustained major damage and began falling behind as the lead bombers ducked into an opportune series of storm clouds for cover. The last that was seen of Captain Pease and his Flying Fortress was the burning bomb bay tank he jettisoned from his doomed airplane.

Captain Harl Pease’s posthumous award of the Medal of Honor recalled his determination to complete a mission in spite of the many reasons that could have excused him. It says in part:

On December 2, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented the second Medal of Honor earned by an Army airman of World War II to the parents of Harl Pease. The accompanying citation gave a true picture of the man’s courage and tenacity. Every effort is made to ensure that any citation for an award as dignified as the Medal of Honor is both accurate and honest. The only error in Harl Pease’s Medal of Honor citation can be found in a single sentence:

On December 2, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented the second Medal of Honor earned by an Army airman of World War II to the parents of Harl Pease. The accompanying citation gave a true picture of the man’s courage and tenacity. Every effort is made to ensure that any citation for an award as dignified as the Medal of Honor is both accurate and honest. The only error in Harl Pease’s Medal of Honor citation can be found in a single sentence:

“Capt. Pease’s airplane and crew were subsequently shot down in flames, as they did not return to their base.”

Of the B-17s that conducted the bombing mission against Vunakanau Field at Rabaul on the morning of August 7, 1942, only one did not return. Two Flying Fortresses reached their airfields with a casualty among the crew from the running battle over New Britain with the Japanese Zeroes. The B-17 with tail number 41-2617 was one that should never have been included in the mission. It crashed on New Britain near the confluence of the Mavlo and Powell rivers where a group of natives found the bodies of seven of the airplane’s 9-man crew. These were buried behind a kiln in a Christian mission where they were located after the war and exhumed in 1946 for burial by their living comrades. They were finally last laid to rest on their home soil, with full military honors.

Two of the stricken bomber’s crew had managed to bail out to safety, only to be captured by the Japanese.

On April 30, 1942, Father George Lepping, a Catholic Missionary in the South Pacific, was taken prisoner at Bougainville by the Japanese. Five months later he was transferred to a prison camp on Rabaul. There he found five American airmen, one of whom was Sergeant Chikowsky, a crewman from Harl Pease’s last flight. Another of the American prisoners was the man the Japanese called “Captain Boeing” because he had once piloted a Boeing B-17 bomber. That man was Captain Harl Pease, well respected by fellow prisoners and captors alike, for he was a man of strength and integrity.

In the 1980s, Father Lepping wrote the final chapter in the life of Harl Pease when he recounted meeting Sergeant Chikowsky and Captain Boeing in that prison camp on Rabaul. He also told how on the morning of October 8, 1942, the two survivors of B-17 #41-2617 were taken into the jungle with a work detail consisting of two other Americans and two Australian prisoners. Their task consisted of digging a shallow grave wherein all six unarmed prisoners were buried after their execution by sword. The returning Japanese murderer told Father Lepping, “You go tomorrow.”

Fortunately, that night American B-17s bombed the camp, wounding the Japanese leader who had made the threat. His replacement didn’t know that Father Lepping was marked for similar murder and he survived the war to finish the story of Captain Harl Pease.

Special Acknowledgement

The author is pleased to express sincere appreciation to Mr. Dick Graf for his invaluable contribution to this story. Mr. Graf was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross as the radioman on the B-17 piloted by Captain Lewis when it flew into Del Monte Airfield on March 17, 1942, to fly Douglas MacArthur and his staff from the Philippines to Australia. Mr. Lewis graciously granted a detailed phone interview from his home in Australia in the preparation for this story.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Heroes Stories Index

All Major Military Award Recipients (PDF)

Our Sponsors