Jimmy Doolittle

Jimmy Doolittle

Doolittle’s Tokyo Raid

In Europe and the Far East, World War II had been in progress for nearly two years before the attack on Pearl Harbor. During that period Germany moved swiftly to take and occupy Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and France. When Paris fell it left only Great Britain to resist the Nazi war machine. Japan availed itself of the world’s distraction over events in Europe to begin its own conquest of Indochina, consolidating its near-total control of the Pacific and the Far East.

In Europe and the Far East, World War II had been in progress for nearly two years before the attack on Pearl Harbor. During that period Germany moved swiftly to take and occupy Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and France. When Paris fell it left only Great Britain to resist the Nazi war machine. Japan availed itself of the world’s distraction over events in Europe to begin its own conquest of Indochina, consolidating its near-total control of the Pacific and the Far East.

American efforts at neutrality became increasingly impossible as this aggression escalated around the world. In March 1941 Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act authorizing the sale of U.S. war materials to nations under the Axis attack. American troops were sent to replace British soldiers in Iceland in July, so they could return home to defend their homeland. Soon thereafter American naval and air bases were constructed in Britain, supposedly for British use.

Any hope of American neutrality vanished on December 7, 1941, beneath the oil-covered waters of Pearl Harbor, and 28 hours later Congress declared war on Japan. It was a declaration that was not unanticipated; for half-a-century forward-thinking military planners realized that the day would come when U.S. and Japanese forces would be engaged for control of the Pacific. The most surprising facet of that day’s sneak attack was not that it happened, but where it happened. Few people, other than General William Billy Mitchell who had predicted such an attack fifteen years earlier, believed an assault on Hawaii was possible.

Even before General Mitchell warned in the 1920s of Japan’s designs for domination in the Pacific, Theodore Roosevelt recognized Tokyo’s threat to the Philippine Islands. The islands had been controlled by U.S. forces since the Spanish-American War, and most military planners assumed any Japanese attack against the United States would come on the big island of Luzon. Theodore Roosevelt was the first to initiate a war plan to defend the Philippines, a strategy that evolved over the next four decades. The two nations were given color-coded names; the United States was Blue and Japan was Orange. In 1924 this strategy was given the code name War Plan Orange.

In 1941 War Plan Orange Number 3 was the most recent strategy for an American defense of the Philippines, expected to be in force until the planned issue of independence to the islands in 1946. In essence, it outlined that, in the event of a Japanese invasion, mobile forces on Luzon would abandon Manila to meet the enemy at their landing sites. War planners assumed enemy forces would land on the north side of the island, thus the defense would be waged in the heavy jungles of the Bataan Peninsula. The concept called for delaying guerilla warfare lasting up to six months, thereby allowing U.S. naval forces to reach and reinforce the Philippines from Hawaii.

Following the December 7 attack at Pearl Harbor, this war plan was never fully implemented. In large measure, this was because there was no longer a viable American naval force to steam out of Pearl Harbor to reinforce the Philippines. There wasn’t even an American air force in the region to give aerial superiority to the ground fighters. Despite this unanticipated turn of events, the defenders at Midway, Wake Island, and on the Bataan Peninsula fiercely fought a defensive campaign while hoping for promised reinforcements that would never arrive.

To further complicate the situation in the Pacific, back in Washington, D.C. the President was marshaling for war according to another war plan the Pacific defenders did not even know existed.

War Plan ABC-1

From January to March 1941 American and British military officers met in Washington to shape an alliance to face the threat in Europe. The United States remained technically neutral but was moving ever closer to declaring sides in a struggle that had already yielded most of Europe to the forces of Adolph Hitler. The Lend-Lease Act was the result of these talks. Out of these sessions emerged an agreement as well, to be employed if the United States should be forced into war with both Japan and Germany. Called ABC-1, it was a plan whereby the U.S. President agreed that if faced with a war on two fronts, American forces would employ primarily a defensive reaction in the Pacific while committing the majority of its assets to Europe. Essentially the philosophy was, “Throw everything we’ve got at Europe to defeat Germany first, then take care of matters in the Pacific.”

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor at 7:55 a.m. it was shortly after dinner time in Berlin. Upon hearing the news Adolph Hitler responded: “The turning point! We now have an ally who has never been vanquished in 3,000 years!”

On the morning of December 11 Germany, emboldened by the Japanese victories in the Pacific, declared war on the United States. Within hours the United States Congress responded with a declaration of war against Germany and Italy. The two-front war anticipated in ABC-1 had indeed come to pass.

Arcadia Conference

In the last week of December 1941, U.S., British, and Canadian representatives met in Washington, D.C. to build a military alliance for the protraction of what was now truly a World war. The Arcadia Conference lasted three weeks until January 14 and included a face-to-face meeting between President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

In the last week of December 1941, U.S., British, and Canadian representatives met in Washington, D.C. to build a military alliance for the protraction of what was now truly a World war. The Arcadia Conference lasted three weeks until January 14 and included a face-to-face meeting between President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

In order to defend the Pacific a unified central command structure called ABDACOM (American, British, Dutch, and Australian Command) was established. It illustrated well the cooperation of the nations concerned. British General Sir Archibald Wavell was named central commander with naval forces under the command of American Admiral Thomas Hart. Ground forces were to serve under Dutch Lieutenant General Heiter Poorten and British Air Chief Marshall Sir Richard Pierse was given charge of all Allied Pacific air forces.

In accordance with ABC-1 however, ABDACOM’s mission was primarily defensive, one of stemming the advance of the Japanese forces in the Pacific. Meanwhile, Allied planners turned the majority of their attention towards planning for an invasion of the European continent to strike a death-blow against Berlin.

Prime Minister Churchill and British military planners tended to take a very literal interpretation of ABC-1, anticipating few American assets would be committed to the Pacific campaign. President Roosevelt, on the other hand, though remaining true to the spirit of the “Europe First” doctrine of the agreement, could not forget the humiliating blow struck against the American Fleet in Pearl Harbor. Throughout the last weeks of 1941, seldom did he meet with his own generals that he did not reiterate his desire to strike a blow against the Japanese homeland as quickly as possible.

Because the matter was a priority with their Commander in Chief, America’s top generals and admirals gave it a high priority in their own high-level meetings. By the end of the year, the President’s concept of retaliation had become increasingly critical. Wake Island fell on December 23. Throughout the weeks after the December 9 attack, Japanese General Masaharu Homma landed on Luzon with a large invasion force. In accordance with War Plan Orange, the Philippine and American forces pulled back to Bataan to fight the six-month delaying action called for under War Plan Orange, while awaiting reinforcements from America. The brave defenders did not know what was evident to the American high command in Washington–that no reinforcements would be arriving. There was little doubt back in the United States that soon the Philippines would fall to the Japanese.

Indeed, two days into the new year (1942) Manila was in enemy hands.

A swift American strike at Tokyo was needed for many reasons beyond just the fact that the American President had called for it. At home, the American people needed some good news from the Pacific, some event that would prove that the Japanese were not invincible. The American public was struggling through a range of emotions: outrage, the need for vengeance, fear, and uncertainty.

The military value of a bombing raid on Japan was negligible in comparison to the emotional need for such a victory. But there was a strategic value to be found as well. Japan continued to operate in the Pacific as if it were insulated at home from the effects of war. No one believed that an attack on the Empire was possible, isolated as the islands were by thousands of miles of the vast Pacific. Roosevelt knew that if such an attack DID occur, it would force the enemy to pull back some of its naval and air power to protect its own shores. This would reduce the number of assets the Japanese could commit to their aggressive campaign of conquest in the South Pacific.

Prior to December 7 American military planners had similarly believed Hawaii was insulated from attack by that same expanse of water. Admiral Yamamoto succeeded primarily because the element of surprise allowed him to steam within 250 miles of Oahu, the maximum range of carrier-based torpedo planes. With both warring nations now on alert for attack, it would be impossible for either country to move warships within 400 miles of the other, and that was beyond the range of any aircraft carrier-borne planes. With Hawaii more than 3,000 miles distant, and 2,000 miles separating Tokyo from Luzon, there was no possibility of attack from the few American long-range bombers that had survived the Day of Infamy. America’s huge B-17 Flying Fortresses, nearly all of which had been destroyed at Clark Field, had a two-way range of 800 miles.

The strike President Roosevelt was asking for, the payback mission all of America yearned for, seemed little more than a diversionary pipe-dream. In the real world of military planning, the President was asking for a miracle.

Miracle Workers

Ironically the first hint of a means for an attack on Japan came not from strategy sessions for war in the Pacific, but for the war in Europe. On January 4, 1942, the Arcadia Conference discussions were centered on the problems in North Africa. When Paris fell Germany entered into an armistice with the French government, conceding small areas to token French self-rule. Thus, North Africa was controlled by the pro-Axis, Vichy French government. On January 4 the Allied commanders were contemplating the feasibility of invading North Africa, trying to predict how such a mission might unfold. (Indeed, that invasion, code-named Operation Torch, commenced before the end of the year.)

Airpower predominance, and specifically the role of strategic bombing, was always a fundamental strategy in the plans for the defeat of the Axis. During the discussion about a possible invasion of North Africa came talk of establishing fields from which long-range bombers could operate. The problem, strategists realized, would be in first transporting the bombers into North Africa.

Admiral Ernest King suggested using one of the big aircraft carriers of the Atlantic fleet to transport 80 to 100 bombers to the region. He further explained his concept. It called for a 3-carrier task force with one of the big ships serving as the transport vehicle. One carrier would operate as an escort, its decks prepared to launch fighters to defend the convoy while the third would transport Army fighter airplanes and munitions.

Many of the ideas tossed around in these high-level, top-secret meetings were impractical, if not impossible. That did not stop the desperate war planners from throwing them out for discussion. When the meeting ended General Henry Hap Arnold, Army Air Force Chief of Staff, returned home to contemplate the day’s events. That evening he composed a memo reflecting his thoughts:

“By transporting these Army bombers on a carrier, it will be necessary for us to take them off from the carrier, which brings up a question of what kind of plane–B-18 and DC-3 for cargo?

“We will have to try bomber takeoffs from carriers. It has never been done before but we must try out and check on how long (a distance) it takes.”

General Arnold’s War Plans Division began looking into the technical aspects of large bombers taking off from an aircraft carrier to determine the feasibility of the North Africa invasion. Admiral King’s unusual idea began slowly to take shape when Captain Francis Low, a young Navy submariner, and Admiral King’s operations officer, caught up with him after dinner on January 10. Captain Low laid out his own new angle on the idea:

“Sir, I flew down to Norfolk today to check on the Hornet, our new carrier, and saw something that started me thinking.

“The enemy knows that the radius of action for our carrier planes is about 300 miles. Today, as we were taking off from Norfolk, I saw the outline of a carrier deck painted on an airfield where pilots are trained in carrier takeoffs and landings.

“I saw some Army twin-engine planes making bombing passes at this simulated carrier deck. I thought if the Army had some twin-engine bombers with a range greater than our fighters, it seems to me a few of them could be loaded on a carrier….and used to bomb Japan.”

For the next week, the staff of both General Arnold and Admiral King continued their separate work on the feasibility of Army bombers launching from an aircraft carrier, neither aware of what the other was doing. On January 15 Admiral King placed his air operations officer, Captain Donald Duncan, in charge of the project and asked him to schedule a meeting with General Arnold to share the idea. Both Duncan and Low met with the Air Force commander on January 17.

Hap Arnold heard them out without advising that he was working on a similar concept, then called for a member of his own personal staff. The former Shell Oil executive, who had returned to active duty six months earlier, was the air chief’s “troubleshooter”. The man who entered Hap’s office knew more about airplanes and their capabilities than any man alive. Hap looked him in the eye and asked:

“Jim, what airplane do we have that can take off in 500 feet, carry a 2,000-pound bomb load, and fly 2,000 miles with a full crew?”

“General,” the famous, former stunt-pilot and racer responded with a quizzical look in his eyes, “give me a little time and I’ll give you an answer.” The following day he was back in Arnold’s office with an answer. He advised that it would have to be either a B-23 or a B-25, and even then, it would only be possible if additional fuel tanks could be added.

“One thing I should have added,” Arnold responded, “the plane must be able to take off in a narrow space not over 75 feet wide.”

With a 92-foot wingspan, this new criterion ruled out the B-23. The only aircraft that could get the job done, if indeed it could be accomplished by anything in the Air Force inventory, was the B-25 Mitchell twin-engine bomber, Hap’s trouble-shooter advised. General Arnold thanked the man and then dismissed him to wonder about the strange questions that had been asked. Hap then placed a call to Admiral King. Perhaps the President’s idea of a bombing strike against Japan was possible after all.

Its addition to being a miracle, based upon a premise that had not yet been proven possible, this mission called for unprecedented coordination between Navy and Army elements. Admiral King advised Arnold that Captain Duncan would handle all the Naval aspects of any such mission and that he would work closely with whomever Hap appointed to handle the Army’s side of the mission. The very next day Arnold called his trouble-shooter back into his office and laid out the reason for his questions.

“The idea is really simple in concept,” the air chief explained. “We’ll load a few of our B-25 bombers on a Navy aircraft carrier, steam within a reasonable distance of Japan itself, and launch the bombers. These Army pilots will fly over the Japanese homeland, bomb military targets, and then continue across the Sea of Japan to land safely in China.”

The young lieutenant colonel who had spent his life flying every conceivable type of airplane under all imaginable conditions nodded in assent. “I think,” he announced, “that this just might work.”

“I need someone to take this project over, get the planes modified and train the crews,” the general stated.

“And I know where you can get that someone,” the trouble-shooter responded with a smile.

“O.K., Jim. It’s your baby. You’ll have first priority on anything you need to get the job done. Get in touch with me directly if anybody gets in your way.”

No person, circumstance, nor any seemingly impossible situation had ever got in the way of James H. Jimmy Doolittle when he set out to do what others deemed impossible. This time his success or failure would matter more than it ever had in anything he had ever done in his exciting and eventful life.

Jimmy Doolittle

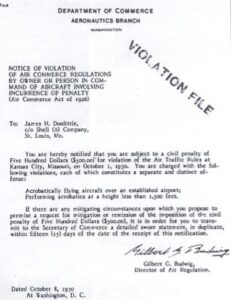

When Major James H. Doolittle was called to active duty on July 1, 1940, he was a 43-year old reservist who was voluntarily leaving a distinguished position with the Shell Oil Company for a job that paid one-tenth of what he was used to earning. It was also the result of his own voluntary act in the face of a war that he firmly believed would eventually draw the United States out of its position of neutrality.

When Major James H. Doolittle was called to active duty on July 1, 1940, he was a 43-year old reservist who was voluntarily leaving a distinguished position with the Shell Oil Company for a job that paid one-tenth of what he was used to earning. It was also the result of his own voluntary act in the face of a war that he firmly believed would eventually draw the United States out of its position of neutrality.

Several leading American aviators had visited Germany since the Armistice that ended the first world war and had witnessed the building of the formidable Luftwaffe. All of them returned home to marvel at the great war machine being created, and to warn of the potential danger for America if our own Air Forces were not given a high priority. In 1922 Billy Mitchell returned from Germany to announce that American aviation lagged behind the rest of the world and “at this time if we should be attacked, no one can tell what the duties of these three arms (Army, Navy, Air Force- would be).” In the early 1930s, WWI Ace of Aces Eddie Rickenbacker was given an unprecedented welcome and tour of the German war machine. He returned home to draft a plan for aid to Germany that he believed could avert a future war. His ideas were rejected as quickly as were Mitchell’s plans for a separate Air Force.

Charles A. Lindbergh visited Germany four times in that decade and was dutifully impressed by the German air forces. He was also visibly concerned. Lindbergh could foresee the war that was destined to come and became one of the most vocal proponents of American isolationism. In 1938 Lindbergh wrote to Hap Arnold to suggest that the air chief himself visit Germany to witness the truth of his warnings. For diplomatic reasons, however, General Arnold declined and was relegated to understanding what was happening in Europe from the reports of Rickenbacker, Lindbergh, and Jimmy Doolittle.

Doolittle made his first visit to Germany during a 21-nation promotional tour for Shell Oil in 1930, only months after he left active duty for reserve status and a well-paying private-sector job. What he saw of the German emphasis on building military air power became a source of concern, one that increased when he visited Germany again in 1937. Upon returning home, though still employed by Shell with only an Army reserve commission, Doolittle became a strong voice for building up America’s air power to ensure a future defense.

In the Spring of 1939, Doolittle made his third visit to Germany and came home more concerned than ever. General Hap Arnold was a personal friend and Doolittle visited with the air chief at his office in Washington, D.C. upon his return. Unlike Lindbergh, who foresaw the coming war and hoped for American neutrality, Doolittle anticipated that war and realized that the United States would not be able to avoid taking sides.

“I told Hap that I was totally convinced that war was inevitable, that the United States would be involved in hostilities, and that we would be unable to remain aloof from whatever happened in Europe. I was so sure of it, in fact, that I told him I was willing to give up my job with Shell and serve full time or part time, in uniform or out, in any way he thought would be useful.”

Jimmy Doolittle

I Could Never Be So Lucky Again

General Arnold was certainly concerned by what he had heard about the situation in Germany, but could not recall a reservist with such high rank as Major until the beginning of the next fiscal year. Within two weeks of that meeting, Hitler invaded Poland and the Nazi war machine began its march through Europe. Before the new fiscal year began ten months later, Hitler had taken Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. On June 22 Paris fell and the handwriting was on the wall for all to see. More than ever Hap Arnold needed a man with the knowledge and experience of reserve Major Jimmy Doolittle. He eagerly anticipated the beginning of the new fiscal year.

On July 1 Doolittle took a 70% pay cut to help his country prepare for war. In August the mighty German Luftwaffe launched its fury on its only viable remaining European threat during the historic Battle of Britain. In September Major Doolittle requested permission from General Arnold to visit England to observe and report on the war effort. Shortly after his return, all hope of American neutrality vanished beneath the smoke of Pearl Harbor. The United States was at war on two fronts.

On Christmas Eve 1940, General Arnold transferred Major Doolittle to his staff in Washington, D.C. to serve as a troubleshooter. This was ten days after Doolittle’s 45th birthday and he was an “old man” by contemporary Air Force standards. What the old man lacked in youth, however, he more than made up for inexperience. Few people have ever lived as much in a lifetime as Jimmy Doolittle had lived through in the first half of his own. Those first 45 years would prove to be just the beginning.

Doolittle – The Fighter

General Arnold’s trouble-shooter was a fighter, first because he had to be, then because he was so good at it. Born December 14, 1896, in Alameda, California, little Jimmy spent most of his early years far north in Alaska where his father had followed the great gold rush.

General Arnold’s trouble-shooter was a fighter, first because he had to be, then because he was so good at it. Born December 14, 1896, in Alameda, California, little Jimmy spent most of his early years far north in Alaska where his father had followed the great gold rush.

Jimmy and his mother joined the senior Doolittle in Nome at the turn of the century. The little kid with long curly locks of hair was not yet three years old. Two years later when he started school, those curls become a magnet for trouble, further enhanced by the fact that Jimmy was so small as to seem vulnerable in a region where only the tough survived. At age five, when a larger Eskimo boy tried to take advantage of the smaller boy’s size, Jimmy Doolittle the fighter was born. Within minutes his opponent was racing home with blood flowing from his nose, while a frightened Jimmy ran home afraid, he had killed his tormentor.

In 1908 Frank and Rosa Doolittle parted and Jimmy returned to California with his mother. Eleven years old and toughened by years of defending himself, Doolittle was more than a match for neighborhood bullies no matter how big they were, and his reputation quickly spread. He was still small for his age and certainly wasn’t a polished fighter. On the contrary, when confronted, he tended to become a windmill of poorly aimed blows. But his aggressive fury made him a threat to any who dared to underestimate the little guy.

It was Forest Bailey, one of Jimmy’s teachers, who finally took the young scrapper under his wing and taught him how to fight properly. He also taught the young man an important philosophy that would contribute to his success in a variety of fearsome situations in the years to follow: “You get mad when you fight, and if you lose your temper, you’re going to get licked sooner or later because you let your emotions rule your body instead of your head.” By 1912 Jimmy won the West Coast high school amateur championship in the bantam-weight class. The boy had learned to use his mind as well as his fists.

Doolittle – The Scientist

In 1913 aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss set a new speed record of 55 miles an hour during an aviation exhibition in California. Among the fascinated spectators was 16-year-old Jimmy Doolittle. For the young scrapper who by his own admission “didn’t have a fondness for academic classes but did have a liking for the shop courses working on gasoline engines and wood lathes,” it was the beginning of a love affair with the air.

In 1913 aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss set a new speed record of 55 miles an hour during an aviation exhibition in California. Among the fascinated spectators was 16-year-old Jimmy Doolittle. For the young scrapper who by his own admission “didn’t have a fondness for academic classes but did have a liking for the shop courses working on gasoline engines and wood lathes,” it was the beginning of a love affair with the air.

Doolittle’s first airplane was a glider he built himself shortly after the air exhibition, based upon plans he found in a 1910 copy of Popular Mechanics. When Doolittle couldn’t get his glider airborne from the slope of a small hill, he convinced a friend to provide more speed by tying it to the rear bumper of his car. The result was Doolittle’s first airplane crash and the destruction of his crude glider. Jimmy himself was dragged for a hundred feet before his friend could halt the car, but the battered and bloody young daredevil refused to give up. Soon he was building his second airplane, and boxing for pay to earn enough cash to purchase an engine. Before the inaugural flight of his second airplane, a passing thunderstorm derailed his plans and dashed his creation into pieces in a neighbor’s lawn.

After graduating from high school in 1914, Jimmy returned to Alaska to rejoin his father. The two of them built two houses to earn money, but young Jimmy and the elder Frank Doolittle didn’t get along well. Jimmy left to pan for gold, then returned home the following year to pursue an engineering curriculum at a Los Angeles junior college. The kid who “didn’t have a fondness for academic classes” developed new interests in science and math, and went on to attend the University of California School of Mines at Berkeley, where he also became the school’s middleweight champion boxer (though he was in fact, only a lightweight.)

In the fall of 1917, Doolittle left school to enlist in the Aviation Section of the Army Signal Corps. In January of the following year, after eight hours of flight training at Rockwell Field near San Diego, Doolittle soloed. He later wrote of his first flight, “If there is such a thing as love at first sight, my love for flying began on that day during that (first) hour.” On March 11 he received his wings and was commissioned as an Army Air Service second lieutenant. Though this marked the beginning of his life as a military man the young pilot remained a scientist for the rest of his life.

Doolittle’s experience as an aviation engineer prompted UC to give him credit for his last year of college and award him a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1922. The following year he pursued a Master of Science Degree at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and in 1925 he received his Doctor of Science degree from MIT as well. (In the course of his lifetime Jimmy Doolittle received a total of eight honorary degrees as well.)

Doolittle – The Soldier

Even as Lieutenant Doolittle was getting his wings, other American pilots were flying their first combat missions in France. Doolittle wanted to join them; he had, after all, been a gutsy scrapper his entire life. Instead, he was assigned as an instructor, first at Camp Dick, Texas, and then back at Rockwell Field. For Doolittle, the one consolation in missing out on the war in France was that at least he was close to home and his young wife. On Christmas Eve, just three months earlier, Doolittle had married his high school sweetheart “Joe” (Josephine Daniels.)

Even as Lieutenant Doolittle was getting his wings, other American pilots were flying their first combat missions in France. Doolittle wanted to join them; he had, after all, been a gutsy scrapper his entire life. Instead, he was assigned as an instructor, first at Camp Dick, Texas, and then back at Rockwell Field. For Doolittle, the one consolation in missing out on the war in France was that at least he was close to home and his young wife. On Christmas Eve, just three months earlier, Doolittle had married his high school sweetheart “Joe” (Josephine Daniels.)

By the end of 1918, the war in Europe ended and Lieutenant Doolittle knew that his opportunity to be a part of the elite young heroes who had pioneered aerial combat had vanished. Disappointed, he devoted himself to becoming one of the leading pioneers of peace-time aviation, combining his keen mind, his mechanical aptitude, and scrappy nature to improving aviation and expanding the limits on what could be expected from an airplane.

Doolittle’s first test flights derived from a less-than-admirable motivation. His early stunts were more to relieve the boredom of routine aviation than to research the capability of his airplane for scientific advancement. In May 1921 he was assigned to Langley Field in Virginia as an engineering officer during General Billy Mitchell’s historic bombing tests against naval ships. Doolittle flew some of the bombing missions and for one day served as an aide to General Mitchell, of whom he later wrote: “During this period…he almost wore me out. I’ve never moved so fast or worked so hard in my life.” Doolittle gained a deep respect for the rogue air advocate, despite his sense that Mitchell was less than wise in the manner in which he accomplished his aims.

Doolittle – The Daredevil

Mitchell was eager to see his airmen accomplish spectacular new feats, even trying to promote an around-the-world flight. It took three years for Mitchell to convince the Army to undertake that highly publicized event, but in 1922 Lieutenant Doolittle convinced air chief General Mason Patrick to allow him to attempt a transcontinental flight in less than 24 hours. Such a feat had never been accomplished.

Mitchell was eager to see his airmen accomplish spectacular new feats, even trying to promote an around-the-world flight. It took three years for Mitchell to convince the Army to undertake that highly publicized event, but in 1922 Lieutenant Doolittle convinced air chief General Mason Patrick to allow him to attempt a transcontinental flight in less than 24 hours. Such a feat had never been accomplished.

On August 4 Doolittle took off from Pablo Beach, Florida in a DH-4 Flaming Coffin. As he taxied towards the sea a wave rolled in to snag the wheels and flip his plane into the water. Doolittle was drenched and embarrassed, but not discouraged. Less than a month later Doolittle made a night-takeoff from Pablo Beach to fly west and cross the United States in 22.5 hours (21 hours and 19 minutes flying time). It was the first time any aviator had crossed the United States in fewer than 24 hours and the first of many records that would make Jimmy Doolittle heroin peacetime. In 1925 Doolittle won the Schneider Cup race setting a new speed record for seaplanes of 245 miles per hour. In 1927 he became the first pilot to execute the outside loop, a move so dangerous that Army pilots were subsequently forbidden to attempt it.

On September 1, 1929, Doolittle was flying at the Cleveland Air Races before a large crowd. Though under orders NOT to do an outside loop he determined to impress the crowd with at least the first half of his now-famous stunt. After climbing to 2,000 feet he started to dive when his wings broke. While the fuselage trembled and plummeted earthward, Doolittle struggled to unbuckle his seat belt. No sooner was the catch broken than the force of the shaking cockpit literally threw the pilot into the air. Doolittle reached for his ripcord to complete his first emergency parachute jump and become a member of the Caterpillar Club. (The Caterpillar Club was an informal club composed of those aviators who had to make a parachute jump to save their life.) Later, when required to fill out a report on the incident, Doolittle was brief and to the point:

Q: Cause for Emergency Jump?

A: Wings broke.

Q: Describe method of leaving the aircraft.

A: Thrown Out.

Indeed, for wisdom and maturity, James H. Doolittle came to represent for the Army Air Force in World War II, the man contained all of the fighting spirit of Frank Luke, the impetuosity of Eddie Rickenbacker, and the unconventional manner of getting the job done of Billy Mitchell. The first AIR hero of World War Two may well have been a combination of all the great air heroes of the first war. By his own admission, “I was not an exemplary pilot in those days.” More than once he was chastised for his unorthodox behavior. His pilot’s license was suspended in 1937 for flying below 1,000 feet over a congested area. But whatever the young aviator did wrong, it was what he did right that impressed the nation and made him a celebrity of sorts.

As Doolittle’s exploits made him a national figure, more and more his efforts to push the envelope became less for publicity and more for the advancement of the science of aviation. In 1929 the intrepid airman allowed himself to be “sealed blind” in the cockpit of his NY-2 airplane to take off, conduct a 15-minute flight, and then land. He was the first pilot to fly blind, using only instruments to navigate.

That first instrument-only flight was one of Doolittle’s final spectacular feats for the U.S. Army. Late in 1929, the Shell Oil Company offered him the opportunity to join their aviation program at a salary triple the $200 a month he earned as an Army aviator. With two grown sons in the family, Doolittle accepted the offer, resigning his commission on February 15, 1930. During the years he worked for Shell Doolittle remained an Army Air Corps reservist and was promoted to Major, skipping the rank of Captain.

Doolittle’s flights for Shell brought the company high visibility and positive publicity. In 1930 he toured 21 nations for Shell to promote aviation, including his first trip to Germany. During stress-tests in 1931, a wing of Doolittle’s Curtis Hawk airplane sheared off when his airspeed indicator neared 300 miles per hour. For the second time, a parachute saved his life, making him a 2-time member of the famous Caterpillar Club in which Charles Lindbergh held the record with 4 emergency jumps. For Doolittle, there would be yet a third.

In 1932 Doolittle repeated his transcontinental feat, this time making the trip in 11 hours and 15 minutes. He was now the first person to cross the United States in fewer than 12 hours. The same year he flew the Gee Bee R-1, a squat and stubby racer, to win the Thompson Trophy and $4,500. This was also the year Doolittle put racing behind. For more than a decade he had raced, not just for the thrill but because he believed that the competition promoted efforts to improve both the vehicle and its engine. Through the remainder of the decade until his return to active duty in 1941 Doolittle became more of a “flying ambassador” than a “flying fool”.

In 1932 Doolittle repeated his transcontinental feat, this time making the trip in 11 hours and 15 minutes. He was now the first person to cross the United States in fewer than 12 hours. The same year he flew the Gee Bee R-1, a squat and stubby racer, to win the Thompson Trophy and $4,500. This was also the year Doolittle put racing behind. For more than a decade he had raced, not just for the thrill but because he believed that the competition promoted efforts to improve both the vehicle and its engine. Through the remainder of the decade until his return to active duty in 1941 Doolittle became more of a “flying ambassador” than a “flying fool”.

Doolittle – The Trouble-Shooter

When Major Doolittle returned to active duty in 1941, he had already given the United States Army his youth, his tremendous personal abilities, and had personally contributed much to reshape the future of aviation. His sons were young adults, one entering Army Air Force Flight Training while the other prepared to enter the military academy at West Point. Doolittle was a well-paid, highly regarded Shell Oil executive with a comfortable lifestyle, an enduring marriage, and 7,730 hours of flying time.

Despite so admirable a history, Jimmy Doolittle could see war coming to the country he loved and was determined to do his part. On December 8, while the nation reeled from the shocking reports coming in from the Pacific, Doolittle penned a letter to General Arnold requesting to be relieved of his duties on the staff and reassignment to a tactical air unit. His request was denied, as were additional such pleas, and Doolittle recalled: “I was very disappointed. I had missed combat in the first war. Now it looked like I was going to be chained to a desk shuffling paper for this one.” The blow was only somewhat lessened by his unexpected promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and appointment on Christmas Eve to the personal staff of General Arnold.

The trouble-shooter’s first assignment in the last week of December was to examine problems with the B-26 Martin bomber, a new multi-engine airplane that had been experiencing several engine failures and deadly crashes. Doolittle tested the troublesome bomber and immediately liked it. The problem, he determined, was with the pilot training. Men who had flown only single-engine airplanes or those who had never landed an airplane with a nose wheel had simply lost confidence in the bomber’s reliability. The most common complaint was that if one engine failed, the craft could not be safely landed. “It’s impossible,” the exasperated pilots told Doolittle, “to turn into a dead engine and safely land the ship.”

To counter this, Doolittle gathered the pilots to watch while he took one of the B-26s in the air. He cut the left engine during the takeoff and then turned into the dead engine to circle back and safely land. He repeated the maneuver in the opposite direction with the right engine out. He noted: “I did this without a copilot, which made a further impression. This convinced the doubters that all of these ‘impossible’ maneuvers were not only possible but easy if you paid close attention to what you were doing. I had no trouble getting volunteers after each demonstration.”

While Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle was solving the problem with the B-26, the President of the United States was announcing to his top commanders that he wanted to conduct a bombing strike on the island of Japan. On that day almost any rational military leader would have said, “That’s just not possible.”

While Lieutenant Colonel Doolittle was solving the problem with the B-26, the President of the United States was announcing to his top commanders that he wanted to conduct a bombing strike on the island of Japan. On that day almost any rational military leader would have said, “That’s just not possible.”

Less than three weeks later General Arnold laid out the plan to accomplish the President’s impossible mission, by launching Army medium-range bombers from a Navy aircraft carrier. Again, the rational mind would have responded, “That’s impossible!”

When the air chief announced to his trouble-shooter: “O.K., Jim. It’s your baby.”, he knew that all hope of accomplishing the impossible lay with one man and the volunteer airmen who would follow him. They became:

Jimmy Doolittle’s Raiders

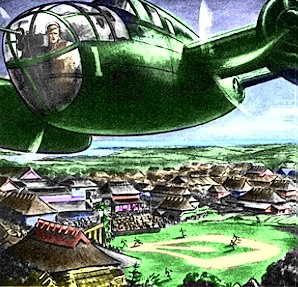

If all of the other factors in and of themselves were insufficient to render the bombing of Tokyo nearly impossible, the logistics of the plan presented a problem that might have made such a mission quite impractical. The top-secret program that Colonel Doolittle labeled Special Aviation Project No. 1 called for a Navy aircraft carrier to steam through thousands of miles of enemy-controlled waters in the Pacific to somehow slip within 500 miles of the enemy homeland. There, Army bombers would take off from the carrier’s short deck to bomb military targets. The aircraft would be unable to land back on the carrier, this would fly on to land in China more than 1,000 miles further west. The plan required a level of Army/Navy cooperation unprecedented in American military history.

If all of the other factors in and of themselves were insufficient to render the bombing of Tokyo nearly impossible, the logistics of the plan presented a problem that might have made such a mission quite impractical. The top-secret program that Colonel Doolittle labeled Special Aviation Project No. 1 called for a Navy aircraft carrier to steam through thousands of miles of enemy-controlled waters in the Pacific to somehow slip within 500 miles of the enemy homeland. There, Army bombers would take off from the carrier’s short deck to bomb military targets. The aircraft would be unable to land back on the carrier, this would fly on to land in China more than 1,000 miles further west. The plan required a level of Army/Navy cooperation unprecedented in American military history.

On January 31 Captain Duncan flew to Norfolk, Virginia, to meet with the captain of the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier the USS Hornet. Without advising Captain Marc Mitscher the ship’s skipper of the purpose for what was about to occur, Duncan arranged for three B-25 Army bombers to be loaded on the deck the following day.

On Sunday morning two of the three bombers were hoisted to the carrier deck and then Captain Mitscher pointed the Hornet out to sea. The third B-25 had developed engine trouble and was left behind. Shortly after noon, the Hornet was facing into the wind when Lieutenant John Fitzgerald lined up on the flight line with both engines revved to the maximum. On a signal from the flight officer, the big bomber rolled forward to lift off easily. Minutes later Lieutenant James McCarthy took off in the second bomber.

After a week of practice on a simulated carrier deck back at the auxiliary airfield at Norfolk, the two pilots had just proven that a bomber could indeed take off from an aircraft carrier. It was the only live-action test to answer that question prior to the actual mission launch, but it was enough. Captain Duncan then flew to Pearl Harbor to plan other aspects of the Navy’s role in the upcoming mission while Lieutenants Fitzgerald and McCarthy returned to their normal flying duties, unaware of the importance of what they had just accomplished.

The Hornet continued its final shake-down tests while the February 1 takeoff by the Army bombers remained shrouded under the tightest secrecy. Already the 809-foot, the 20,000-ton carrier had been selected for the President’s Pay Back Mission. She was scheduled to leave Norfolk on March 4 to sail for San Francisco via the Panama Canal. Admiral King and General Arnold advised Colonel Doolittle to be prepared to launch his mission from there on April 1. It didn’t leave the trouble-shooter much time to do all that needed to be done to ensure the success of the strike that many, had they known of the daring plan, would have still said was nearly impossible to achieve.

The Hornet continued its final shake-down tests while the February 1 takeoff by the Army bombers remained shrouded under the tightest secrecy. Already the 809-foot, the 20,000-ton carrier had been selected for the President’s Pay Back Mission. She was scheduled to leave Norfolk on March 4 to sail for San Francisco via the Panama Canal. Admiral King and General Arnold advised Colonel Doolittle to be prepared to launch his mission from there on April 1. It didn’t leave the trouble-shooter much time to do all that needed to be done to ensure the success of the strike that many, had they known of the daring plan, would have still said was nearly impossible to achieve.

Among those in the know, there was still much doubt as to the full feasibility of the planned raid. The successful carrier takeoffs of February 1 had been accomplished using empty B-25s. Doolittle’s Raiders would have to lift off in bombers carrying enough fuel for a 2,000-mile flight, loaded with a ton of bombs, and suitably armed to defend themselves against enemy fighters should they appear.

The toughest modification Doolittle’s specially ordered B-25s would need was the extra fuel tanks. An auxiliary 255-gallon rubber tank was fitted into the top of the bomb bay, requiring that special racks be manufactured for the four 500-pound bombs each plane would carry. A 160-gallon rubber tank was manufactured and installed in the crawlway above the bomb bay, designed to collapse when it had been emptied so that the passageway would be cleared. The third tank was even more rudimentary. It was placed in the area of the fuselage where the lower turret was removed. It would be refilled when empty by the rear gunner, who would carry 10 five-gallon cans of fuel in the rear compartment.

Through the end of January and into the month of February Colonel Doolittle designed the modifications, and then re-modifications, of what would grow to a fleet of 24 bombers. At the same time the 34th, 37th, and 95th squadrons of the 17th Bombardment Group and its associated 89th Reconnaissance Squadron were ordered to report to Columbia Army Air Base in South Carolina. These experienced B-25 pilots had, for the most part, been flying coastal submarine-watch patrols out of Pendleton, Oregon. Now they were told they would fly similar patrols in the Atlantic. They were ordered to Columbia by way of Minneapolis where extra gas tanks would be fitted to their bombers for their East Cost duty.

At the same time word came down from Lieutenant Colonel William Mills and Major John Hilger that volunteers were needed for a top-secret air mission. Almost to a man, the airmen of the 17th Bombardment Group and 89th Reconnaissance Squadron volunteered for a project they knew nothing about beyond the fact that it would be quite dangerous. Colonel Mills delegated to his squadron commanders the task of selecting who would be accepted, and which men would be turned away in disappointment. In all, 24 crews of five men each were selected. All three squadron commanders included themselves in the selection, but Mills needed experienced leaders for other missions and allowed only one of them to join the volunteer squadron. The volunteers who were accepted were ordered to fly on to Eglin Field in Florida, where most arrived in the last two days of February.

On March 3 about 140 pilots and their crew assembled at the Operations Office at Eglin, each man full of questions, every one of them eager to do whatever was necessary to serve their country. Already a ripple of excitement had spread among them with a rumor that Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle was also at Eglin. Few airmen did not know the reputation of the great stunt-pilot and air-racer. When Doolittle entered the room, a hush fell across the anxious chatter. The first thing he said was,

“If you men have any idea that this isn’t the most dangerous thing you’ve ever been on, don’t even start this training period. You can drop out now. There isn’t much sense wasting time and money training men who aren’t going through with this thing. It’s perfectly all right for any of you to drop out.”

A couple of boys spoke up together and asked Doolittle if he could give them any information about the mission. You could hear a pin drop.

“No, I can’t–just now,” Doolittle said. “But you’ll begin to get an idea of what it’s all about the longer we’re down here training for it. Now, there’s one important thing I want to stress. This whole thing must be kept secret. I don’t even want you to tell your wives, no matter what you see, or are asked to do, down here. If you’ve guessed where we’re going, don’t even talk about your guess. That means every one of you. Don’t even talk among yourselves about this thing. Now, does anybody want to drop out?”

Nobody dropped out.

Captain Ted Lawson

Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo

Two days earlier Doolittle had himself checked out on the B-25B, determined to lead his volunteers by example. Captain Duncan assigned Navy Lieutenant Henry Hank Miller to work as an instructor at Eglin, teaching the Army bomber pilots what they would need to know in order to take off from an aircraft carrier. If the men were surprised to get their initial instruction from a Navy man, they adapted quickly. Doolittle himself trained studiously under Miller determined to do himself, whatever he asked of his men.

Among the volunteers, only the men Doolittle selected for his squadron leadership were given the details of the mission. While the men practiced short-field takeoffs at the airfield, modification continued on their aircraft. Some were ingenious, others were absolute necessities, and nearly all were strange to the men who still knew not the nature of their mission.

Doolittle realized that the probability of at least one of his airplanes being shot down over Japan was quite high, posing the risk that the top-secret Norden bombsight might fall into enemy hands. So, he had them removed from all the B-25s and replaced them with a simple “Mark Twain” site that was created in the machine shops at Eglin for about 20 cents each. The crude device was developed by Doolittle’s gunner and bombing officer Captain Ross Greening and actually proved to be more effective for low altitude bombing than the more expensive Norden bombsight.

Doolittle realized that the probability of at least one of his airplanes being shot down over Japan was quite high, posing the risk that the top-secret Norden bombsight might fall into enemy hands. So, he had them removed from all the B-25s and replaced them with a simple “Mark Twain” site that was created in the machine shops at Eglin for about 20 cents each. The crude device was developed by Doolittle’s gunner and bombing officer Captain Ross Greening and actually proved to be more effective for low altitude bombing than the more expensive Norden bombsight.

Greening also developed an unusual manner of protecting the bombers from attack from the rear. Each bomber was fitted with two broomsticks protruding from the tail cone, each painted black to look like the barrel of a protective machinegun in hopes it would cause enemy fighter pilots to avoid trying to sneak up behind the bombers.

Modifications had to be made on the specially ordered Delco machineguns that protected other vulnerable areas of the bombers, and the crews were trained in the use of these. Doolittle fitted each bomber with movie cameras to record the effectiveness of the raid and requested special incendiary bombs for the payload.

The day after Colonel Doolittle met with his volunteers for the first time, the USS Hornet sailed out of Norfolk for the Panama Canal. She arrived in San Francisco on March 20. Meanwhile, the raiders trained for their mission while Doolittle split his own time between training with them, overseeing the modifications to their airplanes, and flying back and forth to Washington, D.C. to report to Hap Arnold. On one of those trips, he addressed what he saw as a remaining key problem, leadership of the mission itself. “General,” he advised, “it occurred to me that I’m the one guy on this project who knows more about it than anyone else. You asked me to get the planes modified and the crews trained and this is being done. They’re the finest bunch of boys I’ve ever worked with. I’d like your authorization to lead this mission myself.”

General Arnold believed his trouble-shooter was far too valuable in planning future missions to risk him in leading this one and denied Doolittle’s request. It was not unexpected and Doolittle had his rebuttal well prepared. Perhaps the air chief himself had anticipated the argument for when at last he gave ground it was with what he hoped would be an easy out. “All right, Jim. It’s all right with me provided it’s all right with (General Millard) Miff Harmon.” Arnold was sure that his chief of staff would quickly add his own negative to the air chief’s initial one.

Doolittle quickly excused himself and ran down the hall to General Harmon’s office. “Miff,” he stated after a knock and a quick salute, “I’ve just been to see Hap about that project I’ve been working on and said I wanted to lead the mission. Hap said it was okay with him if it’s okay with you.”

Doolittle’s tactic caught the general unprepared and Harmon replied, “Well, whatever is all right with Hap is certainly all right with me.”

Doolittle smiled, thanked the General, and beat a hasty retreat just as he heard General Arnold’s voice over the squawk box on General Harmon’s desk. Vanishing down the corridor to head back to Eglin he could hear

Hap Arnold’s chief of staff saying with frustration, “But Hap, I just told him he could go.”

When the third intensive week of training for short-runway takeoffs and low-level flying came to a close at Eglin, the USS Hornet was arriving in San Francisco. At Pearl Harbor, Captain Duncan was finalizing a plan that would unite the Navy’s newest carrier with a supporting task force under the USS Enterprise. Preparations complete, Duncan wired a seven-word message to Admiral King in Washington who in turn passed it on to Hap Arnold. Hap called Colonel Doolittle at Eglin to announce: “Tell Jimmy to get on his horse.” It was the green light he had been waiting for.

On March 23 Doolittle called together his group of volunteers. He had accepted more volunteers than the mission required so that if he lost any personnel unexpectedly, he would have trained replacements. Now he dismissed those men who would not be going on the mission, advising them: Don’t tell anyone what you were doing here at Eglin–not your families, wives, anybody. The lives of your buddies and a lot of other people depend on you keeping everything you saw and did here a secret.” Though none of the men still knew the ultimate destination of the Doolittle Raid, or even that it would be a bombing raid, the slightest hint of what the men had been doing might tip off the enemy and lead to disaster. All who failed to make the final cut were disappointed; to a man, they were eager to face whatever danger this secret mission entailed for the greater good of their country.

Two of the specially outfitted B-25s had been damaged during training and were left behind. Their crews were among those dismissed, leaving 22 planes and 110 men to fly to California to meet their Naval transport. Doolittle ordered his pilots to make the cross-country trek at tree-top levels. It was the kind of low-level flight that had caused problems for Doolittle from the Aeronautics Branch of the Commerce Department in previous years and even resulted in his temporary suspension as a pilot. Now he and his men would do it under sanction, as they set out to create a miracle.

The bombers flew first to McClellan Army Air Field near Sacramento where they underwent final inspections. Each bomber’s engine was upgraded with new, 3-bladed propellers during the brief stay. A less welcomed alteration was also conducted, the removal of all radio equipment. “You won’t need it where you’re going,” Colonel Doolittle explained cryptically to his pilots. When the B-25s passed the final muster, they were ordered to fly to the Naval Air Station at Alameda, located on a small island in the San Francisco Bay area.

Pilot Ted Lawson, who later wrote the book Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, recalled that final pre-mission flight. Approaching San Francisco from the west, his crew became excited as they approached the Golden Gate Bridge.

“What about flying under the bridge,” suggested Lawson’s co-pilot Lt. Dean Davenport who was at the controls. Lawson consented and then chaffed nervously as Davenport dropped the nose of the big bomber to slide underneath the suspended structure. “I hoped there weren’t any cables hanging under the span,” Lawson later wrote. “I was half tempted to take over and pull the Ruptured Duck (the name his crew had given to their airplane) up over the bridge at the last moment.”

As the huge structure passed behind the bomber the crew looked ahead to find their airfield. Nearby was the Navy’s newest and biggest aircraft carrier, an impressive sight until the men noticed three B-25s loaded on her deck. “Damn! Ain’t she small,” one of Lawson’s crew muttered into the interphone. For the first time, the reason for all the short-field takeoffs practiced in the preceding weeks became stunningly clear.

Hornet’s Nest

If the crew of the USS Hornet had been perplexed two months earlier by the sight of two B-25s being loaded onto and then taking off from the deck of their ship, the loading of fifteen B-25s at San Francisco must have seemed like a bad April Fool’s Day prank. Doolittle originally planned to load eighteen of his bombers for the mission, but as each airplane was lifted by crane and tied to the fantail of the carrier, the deck grew increasingly smaller.

If the crew of the USS Hornet had been perplexed two months earlier by the sight of two B-25s being loaded onto and then taking off from the deck of their ship, the loading of fifteen B-25s at San Francisco must have seemed like a bad April Fool’s Day prank. Doolittle originally planned to load eighteen of his bombers for the mission, but as each airplane was lifted by crane and tied to the fantail of the carrier, the deck grew increasingly smaller.

The unspoken but unmistakable look of incredulity in the eyes of his pilots told Doolittle that his airmen were unsure that their bombers could safely take off from the floating runway. He decided to load a sixteenth B-25 for the purpose of addressing that concern. One hundred miles out to sea he planned to launch that extra bomber to fly home for the sole purpose of proving to his men that it could be done. Hank Miller, the Navy lieutenant who had trained the men for this moment, boarded the Hornet with the crew. He would return with to his duty station on the mainland with that sixteenth bomber. (Originally Miller came aboard to supervise the loading of the aircraft and had no orders to sail with the Hornet when it departed San Francisco.)

The sailors who quickly and professionally did their job of loading and tying down the Army airplanes were obviously curious about what was transpiring. Some of the airmen had begun to guess at their mission, but they remained tight-lipped. Since several of the ship’s officers knew Hank Miller from his days at the Naval Academy, it was common knowledge that he was from Alaska. His presence seemed to indicate that perhaps the Hornet was bound for Alaska to deliver the cargo tied to its deck. It appeared this would be an inglorious first assignment for the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier.

Though no tension was evident among the men of the two different branches of service, the sailors showed no deference to the presence of the airmen. Lieutenant Lawson later pointed out that though he outranked the Naval ensigns with whom he was assigned to bunk, they slept on bunks and pointed him to a small cot in the corner.

On the afternoon of April 2, the Hornet sailed out of San Francisco Bay under sealed orders, passing beneath the same bridge Lawson had flown under a day earlier. Accompanying the big carrier were 2 cruisers, 4 destroyers, and 1 tanker. Under the command of Captain Mark A. Mitscher aboard his flagship the Hornet, the 8-vessel force was called Task Group 16.2. Instead of sailing northward towards Alaska, the convoy steamed westward towards Hawaii.

On the afternoon of April 2, the Hornet sailed out of San Francisco Bay under sealed orders, passing beneath the same bridge Lawson had flown under a day earlier. Accompanying the big carrier were 2 cruisers, 4 destroyers, and 1 tanker. Under the command of Captain Mark A. Mitscher aboard his flagship the Hornet, the 8-vessel force was called Task Group 16.2. Instead of sailing northward towards Alaska, the convoy steamed westward towards Hawaii.

When the California coastline vanished in the distance Captain Mitscher had his signal officer flash a message to the other vessels in the group, then delivered the same message himself over the Hornet’s loudspeaker:

“This force is bound for Tokyo.”

The announcement was greeted with cheers that could be heard across the swells of the otherwise empty Pacific.

While en route, Doolittle’s airmen began daily briefings to cover all aspects of their role in the mission. The Hornet was destined to steam to an area northwest of Midway Island where it was to rendezvous with the eight ships of Task Group 16.1. The united force would then become Task Force 16 under Vice Admiral William Bull Halsey, and proceed through more than 1,500 miles of enemy-controlled ocean to within 500 miles of Japan. There, the B-25s would be launched to bomb military installations on the Japanese home island.

While en route, Doolittle’s airmen began daily briefings to cover all aspects of their role in the mission. The Hornet was destined to steam to an area northwest of Midway Island where it was to rendezvous with the eight ships of Task Group 16.1. The united force would then become Task Force 16 under Vice Admiral William Bull Halsey, and proceed through more than 1,500 miles of enemy-controlled ocean to within 500 miles of Japan. There, the B-25s would be launched to bomb military installations on the Japanese home island.

The mission had a secondary purpose as well. Since the beginning of the war, the President had wanted to base American bombers in China. After Doolittle’s B-25s dropped their payloads they were expected to proceed southeast to cross the Chinese coastline. The Japanese controlled the coast all the way from Hong Kong to Shanghai, so the bombers were expected to proceed deep inland to refuel at prepared airfields, and then continue further inland to base out of Chungking.

On April 3 Doolittle had Lieutenant Dick Joyce prepare the sixteenth bomber for the planned demonstration he hoped would reassure his pilots that indeed a B-25 could get off the carrier safely.

I asked Hank (Navy Lt. Henry Miller) to get up into the cockpit (of Joyce’s bomber) with me. “Hank, that deck looks mighty short to me,” I told him, implying that I wondered if Joyce could get off safely.

“Don’t worry about it, Colonel,” he said. “You see that toolbox way up there on the deck ahead? That’s where I used to take off in fighters.” His confidence was encouraging. He was not only willing but eager to ride in the B-25 that would prove how easy a takeoff would be.

“What do they call ‘baloney’ in the Navy?” I said, facetiously. I went to the bridge to see Captain Mitscher and told him I wanted to take that sixteenth bomber with us.

A few minutes later, Hank was called to the bridge. Mitscher said, “We’ve got a light wind. You probably can’t get 40 knots down the deck, Miller. Still want to try it?”

Hank assured him that he did and that they could get off in less space than the 450 feet available with the Hornet at top speed.“Do you have any of your clothes aboard?” Mitscher asked Hank.

“Yes, sir. I do because we’re going to take that B-25 all the way back to Columbia, South Carolina. Why do you ask, sir?”

“Well, if you think it’ll be so easy, we’ll take that sixteenth bomber with us.”

Jimmy Doolittle

I Could Never Be So Lucky Again

Lieutenant Miller was initially quite concerned by this change in plans, not because he was eager to part ways with the airmen, he had spent a month training to do the impossible, but because he had no orders to be at sea. Captain Mitscher assured Miller that he would not be demoted or face other repercussions as a result. Doolittle was pleased to now have a sixteenth bomber for his mission. The happiest man aboard the Hornet that afternoon, however, had to be Lieutenant Joyce who now knew he would be able to join his fellow pilots in creating history.

A new sense of mutual respect developed between the airmen and their navy counterparts when the details of the secret mission unfolded. For the Navy it was a gutsy call, putting all their eggs in one basket in a sense, to get the Raiders within striking distance of Japan. The Pacific Fleet had been devastated by the raid at Pearl Harbor and was trying to fight a war with very limited assets. To accomplish this mission alone the Navy was committing sixteen ships including two of its eight aircraft carriers, and sailing them more than 1,500 miles into enemy waters. During the trip, the Hornet itself would be defenseless against air attack. The fighter planes that normally sat on her deck to take to the skies and repel invaders had to be stowed below to make room for the B-25s.

The sailors viewed the airmen’s mission as suicidal. Ted Lawson later recounted how, after the mission was announced, one of the ensigns with whom he bunked promptly gave up his own comfortable bed and slept on the cot himself. Through more than two weeks of planning, briefing, and sharing quarters, Army and Navy men developed an unusual friendship. That mutual respect, however, did not keep the sailors from taking most of the airmen’s money in the nightly poker games.

At dawn on April 13, Captain Mitscher’s group met up with Task Group 16.1 under Vice Admiral Halsey at 38o North, 180o East. (As a point of reference, Midway Atoll is located at 28o North, 177o East.) Within hours the combined force of sixteen ships, now called “Task Force 16”, had reached the outside edges of the Pacific region controlled by the Japanese navy.

| Task Force 16 Vice Admiral William F. Halsey |

|||

|

|

||

| Also operating in the area were the submarines Trout and Thresher | |||

By April 15 the task force was within 800 miles of Japan. Halsey ordered the refueling of his ships and then sent the tankers back to Pearl Harbor. Now deep into enemy waters, the carriers were making good time but the need for a rapid withdrawal after the bombers were launched was also a concern. Halsey dispatched the slower moving destroyers to return with the tankers, leaving only the two carriers and four cruisers to speed on towards their mission with destiny. Scout planes were routinely dispatched from the Enterprise to watch for, and warn of, any enemy presence. The small American task force would be easily overwhelmed if they were found by the Japanese, so close to the enemy homeland.

Unknown at the time to the American commanders, the Japanese were indeed aware that a convoy was steaming towards Japan. Intercepted radio transmissions indicated the presence of the U.S. Naval Task Force nearby. In response, the enemy began stationing a series of picket boats 650 miles away from its shorelines to watch for and warn of any American ships. Since the Japanese commanders knew that the one-way range of carrier-launched fighters was about 300 miles, the American ships would be detected and destroyed long before they got within striking distance. They had no way of even guessing that the convoy carried long-range Army bombers.

En route, the raiders picked up a report from Tokyo on an English-language radio station in which the Japanese responded to a Reuter’s report that three American bombers had raided Tokyo. The enemy response to the erroneous account was:

“It is absolutely impossible for enemy bombers to get within 500 miles of Tokyo. Instead of worrying about such foolish things, the Japanese people are enjoying the fine spring sunshine and the fragrance of cherry blossoms.”

With the knowledge of what they were about to attempt, the broadcast brought nervous smiles to the faces of Doolittle’s Raiders.

Other radio reports were not so humorous. Shortly after Bataan fell on April 9 Doolittle and his crew became aware of the sad loss in the Philippines and learned of the treachery being laid upon prisoners of the Japanese along the route of the infamous Death March. Every man destined to fly over Tokyo knew there was great potential to be shot down and taken captive, and the subject came up from time to time in the bull sessions that were used to relieve tension. During one of these Doolittle advised his men, “Each pilot must decide for himself what he will do and what he’ll tell his crew to do if that happens. I know what I’m going to do.”

“I don’t intend to be taken prisoners. I’m 45 years old and have lived a full life. If my plane is crippled beyond any possibility of fighting or escape, I’m going to have my crew bail out and then I’m going to dive my B-25 into the best military target I can find. You fellows are all younger and have a long life ahead of you. I don’t expect any of the rest of you to do what I intend to do.”

The original plan was for the mission to begin on the late afternoon of April 19 when the task force was between 400 and 500 miles of Japan. Doolittle planned to take off first, three hours ahead of the rest of his bombers. His B-25 carried four incendiary bombs, which would not only destroy targets on the ground, but would also serve as a beacon in the night skies when the rest of his bombers reached the island. The optimal schedule had the raiders flying over Japan at night when they would be unfettered by barrage balloons, and when they would be difficult targets for enemy fighters. That schedule would have them making landfall on the Chinese coast with the dawn of the following day.

None could have predicted when the launch date was moved forward one day because of the unexpected speed with which the carriers neared Japan, that the time would again be moved forward nearly a dozen hours forcing a daylight raid over Tokyo.

On April 17 Captain Mitscher called Doolittle to the bridge to advise him of the task force’s close proximity to the launch site. It was time to begin gassing and arming the bombers. Doolittle planned to lift off the following afternoon to arrive over Tokyo at dusk. The remainder of his planes were to take off three hours later. “I think it’s time,” Captain Mitscher said, “for that little ceremony we talked about.”

On April 17 Captain Mitscher called Doolittle to the bridge to advise him of the task force’s close proximity to the launch site. It was time to begin gassing and arming the bombers. Doolittle planned to lift off the following afternoon to arrive over Tokyo at dusk. The remainder of his planes were to take off three hours later. “I think it’s time,” Captain Mitscher said, “for that little ceremony we talked about.”

Among the supplies flown out to the Hornet a few days out of San Francisco had been a small package from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox. It contained medals forwarded to him by three former Navy enlisted men who had been decorated by the Japanese during a 1908 visit of the American battle fleet. The men had sent these medals to Secretary Knox requesting they be properly returned. After a rousing ceremony, Doolittle wired them along with an impromptu similar donation from the Hornet’s intelligence officer Lieutenant Commander Stephen Jurika, to one of the bombs intended for Tokyo.

While navy deckhands began the process of fueling the bombers, loading the bombs, and arming the machineguns that evening, Doolittle held a final briefing for his crews. Again, he reminded his men that they were to bomb only military targets, and no matter how tempting it might be, they were not to attack the Imperial Palace. This latter was an instruction he had repeated almost daily to the consternation of his bombardiers. Doolittle the young fighter found success when he learned to fight smart, and not from his emotions. The purpose of this mission was to shake the resolve of the Japanese, and the bombing of a sacred shrine such as this would probably serve only to infuriate the Japanese people and strengthen their resolve.

Before parting, Doolittle advised his men to get a good night’s sleep. He wished them luck and made a final promise. “When we get to Chungking,” he announced, “I’m going to give you all a party you won’t forget.”

Despite Doolittle’s admonition to get a good night’s sleep, most of the men were too nervous to sleep. Many were still awake and playing their last games of poker with the sailors when the Enterprise flashed a warning to the Hornet at 3:00 a.m. that two enemy ships had been sighted. The sounding of general quarters woke everyone aboard and the task force changed course to avoid detection.

At dawn, Halsey sent up patrol planes from the Enterprise to sweep the area. At 6:00 a.m. a Navy scout bomber flew over the carrier to drop a message which was quickly passed up to the bridge. It read: Enemy surface ship–Latitude 36°4N, Long. 153°10E, Bearing 276 Degrees True–42 miles. Believed seen by the enemy.”

Again, Halsey ordered his task force to alter its course to avoid detection. It seemed futile; the Japanese appeared to be everywhere. When morning turned to full light the crew of the Hornet spotted a small vessel less than a dozen miles distant. Captain Mitscher assumed that if he could see the enemy, certainly the enemy could see the big aircraft carrier that was approaching. From the radio room, he received a report that a Japanese radio message had been intercepted nearby. He had to assume that a warning had been flashed to Tokyo.

When one of the scout pilots located yet another enemy ship, this time little more than six miles distant, Admiral Halsey ordered the Nashville to sink it. As the cruiser’s big guns boomed the task force commander flashed a message to the Hornet:

LAUNCH PLANES X

TO COL DOOLITTLE AND GALLANT COMMAND

GOOD LUCK AND GOD BLESS YOU

Colonel Doolittle was on the bridge with Captain Mitscher when the message reached the Hornet. The carrier’s horn blasted through the early morning and then Mitscher announced: “Army pilots, man your planes!” It was 8:00 a.m. and well ahead of the planned take-off time. The Hornet was still 824 statute miles from the center of Tokyo, nearly twice the distance Army pilots had planned to fly. To make matters worse, what had been two weeks of poor weather seemed to be reaching its crescendo. Gale-force winds pushed the spray of 30-foot swells across the Hornet’s deck. It was certainly far from desirable weather for take-off, more so because the launch would be by sixteen overloaded mid-range Army bombers, a feat no one was even sure was possible under optimal conditions.

As a flurry of activity spread across the deck, Doolittle shook hands with Captain Mitscher and headed to his airplane. Mitscher turned the Hornet into the wind and the ship’s big engines strained to get maximum speed. From the cockpit of his B-25, Doolittle listened to the whine of his own engines and looked through the window at a runway measuring only 467 feet. Two white lines marked the placement of the nose and left wheels. If he could keep his bomber aligned on these, his right-wing would clear the carrier’s tower by six feet. It was not a comfortable distance considering the way the ship rolled with the high seas or the shine of salt-water spray across the deck.

Behind the lead aircraft, fifteen pilots and their crews watched anxiously as their commander prepared for takeoff. Months of planning, weeks of intense training, and the risk of much of the Navy’s now-sparse Pacific Fleet had gone into preparing for this moment. The moment of truth had arrived for an experiment no one was sure was even possible. Lieutenant Miller watched the waves rolling in, marking instructions on a blackboard and timing the launch so the Hornet’s deck would be rising on a swell when the signal was given. At 8:20 a.m. the checkered flag dropped, Doolittle released the brakes, and the 30,000-pound B-25 began rolling across the flight deck. Everyone else held their breath.

Behind the lead aircraft, fifteen pilots and their crews watched anxiously as their commander prepared for takeoff. Months of planning, weeks of intense training, and the risk of much of the Navy’s now-sparse Pacific Fleet had gone into preparing for this moment. The moment of truth had arrived for an experiment no one was sure was even possible. Lieutenant Miller watched the waves rolling in, marking instructions on a blackboard and timing the launch so the Hornet’s deck would be rising on a swell when the signal was given. At 8:20 a.m. the checkered flag dropped, Doolittle released the brakes, and the 30,000-pound B-25 began rolling across the flight deck. Everyone else held their breath.

With room to spare Doolittle’s bomber was airborne to cheers and shouts across the deck of the Hornet. Climbing quickly, he circled once to orient his compass with the gyros on the Hornet and then headed west towards Tokyo.

Five minutes later Lieutenant Travis Hoover lifted his own B-25 off the deck. The remaining bombers followed at three-minute intervals. At 9:19 a.m. Lieutenant William Farrow’s sixteenth bomber was airborne and Admiral Halsey ordered his six ships to turn and make a hasty run more than 2,000 miles for home. There was no doubt that once Doolittle’s bombs fell on Tokyo, the full force of the Japanese navy would be out looking for the ships that had brought the raiders so close to their homeland.