Joseph L. Galloway

War Correspondent & Bronze Star Recipient

James G. Fausone

Our time on this earth is never long enough. Joseph L. Galloway died in 2021 after 79 years on this earth. He was the voice of the Vietnam generation. That generation is quickly moving into the good night.

Prolific

Some men are prolific with plenty to say that people choose to hear rather than need to hear. The top five prolific writers of all time are novelists. People with imaginations sprouting words and stories. These authors wrote what people wanted to hear and each wrote over 1,000 books – Corin Tellado, a Spanish romantic novelist; Charles Hamilton, an English novelist; Rvoki Inoue, a Brazilian novelist; and Lauran Bosworth Paine, an American western novelist.

Joe Galloway was prolific at writing what people needed to hear. Fate inserted him into Vietnam as a reporter at the start of the war. He saw firsthand the horrors and heroes of war and reported on the same. He chronicled American wars from Vietnam to Iraq prior to his retirement in 2010. He wrote with knowledge and passion. As he often said, he hated war but loved soldiers. He advised Generals and wrote so mothers knew the challenges their boys faced. What Ernie Pyle was to World War II reporting, Joseph L. Galloway was to Vietnam war correspondents.

Early Years

Joe was a storyteller from birth it seems. Maybe it was his genes. His Galloway-Scottish ancestors found themselves in Ireland before migrating to the United States. It is unclear which branch of the Galloway tree Joe came from but a long and proud storytelling heritage was his birthright. His work on the high school newspaper lit the journalistic storytelling spark.

Joseph L. Galloway was born in Bryan, Texas, on November 13, 1941. Bryan had about 12,000 people in it when Joe was born. His father, Joseph L., fought in the U.S. Army during World War II. His mother was Marian Dewvall. His family relocated to Refugio, Texas, after his father was employed by Humble Oil upon his return from military service. Refugio had a population of 4,500, but after Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017 the population dropped to 2,700. This was the small Texas town from which grew a larger-than-life foreign war correspondent.

Joe explained his journalistic start on Veterans Radio in 2009:

“Joseph L. Galloway: I think I must have been born one. I worked on the school newspaper in high school. I helped start a competitive weekly in my hometown the summer I got out of high school and went off briefly to college. I was driven out of college by an early A.M. German language class taught by a portly lady with badly fitting dentures. In my view the class stood between me and joining the Army. I was 17. I had to browbeat my mother into agreeing to sign for me.

We were two blocks from the recruiting office in Victoria, Texas, when we passed the local newspaper. Mom said “Joe, what about your journalism?” I said, “Good call, Mom, stop the car.” I had been their campus stringer for those few weeks and I walked in and asked if the editor had a job. He did and he hired me on the spot for $35 per week and a free subscription to the paper. I was on my way.”

This started in 1958 a journalism career lasting until retirement in 2010.

Going Into Action

His start was humble at The Victoria Advocate in Victoria, Texas. However, Texas was not big enough to hold him. He moved to the United Press International (UPI) in Missouri and Kansas. UPI then sent him overseas as bureau chief and regional manager. He spent 22 years with UPI in locations such as Tokyo, Vietnam, Indonesia, India, Singapore, Moscow, and Los Angeles.

His time in Vietnam shaped Joe Galloway’s life, as it did for many men of his generation. He arrived in Vietnam in 1965. This was a time of unbridled optimism that the United States would make a quick end to this war. General William Westmorland promised such to the American people.

In March 1965, the U.S. Air Force began Operation Rolling Thunder, starting with over 100 American fighter bombers attacking targets in North Vietnam. Originally scheduled to last eight weeks, Rolling Thunder would instead go on for three years.

This was a time when the first U.S. airstrikes also occurred against the Ho Chi Minh trail. Throughout the war, the trail was heavily bombed by American jets with little actual success in halting the tremendous flow of soldiers and supplies from the North. 500 American jets will be lost attacking the trail. After each attack, bomb damage along the trail was repaired. High-tech destruction was followed by low-tech construction.

During the entire war, the U.S. would fly 3 million sorties and drop nearly 8 million tons of bombs, four times the tonnage dropped during all of World War II, in the largest display of firepower in the history of warfare. The majority of bombs are dropped in South Vietnam against Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army positions. In North Vietnam, military targets include fuel depots and factories. The North Vietnamese reacted to the airstrikes by decentralizing their factories and supply bases, thus minimizing their vulnerability to bomb damage.

Battle of Ia Drang

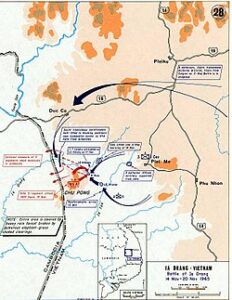

In November 1965, the U.S. and the People’s Army of Vietnam (VPA) met head-on for the first time in the Battle of Ia Drang. Both sides claimed victory. The U.S. inflicted heavy casualties on the VPA, but the battle vindicated the conviction of North Vietnam that its military could slowly grind down the U.S.’s commitment to the war.

Ia Drang is in the central highlands of Vietnam. The battle is notable for being the first large-scale helicopter air assault and also the first use of Boeing B-52 Stratofortress strategic bombers in a tactical support role. Ia Drang set the blueprint for the Vietnam War with the Americans relying on air mobility, artillery fire, and close air support, while the VPA neutralized that firepower by quickly engaging American forces at very close range.

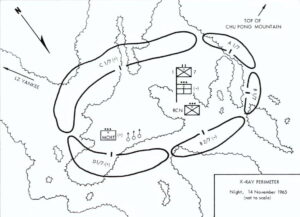

Some 450 men of the First Battalion, Seventh Cavalry, under the command of then Lt. Col. Harold Moore, were dropped into a small clearing in the Ia Drang Valley. They were immediately surrounded by 2,000 North Vietnamese soldiers. Three days later, only two and a half miles away, a sister battalion was brutally slaughtered. Together, these actions at the landing zones X-Ray and Albany constituted one of the most savage and significant battles of the Vietnam War.

Unbeknownst to those in the fight, this battle was seen as an opportunity to test a new theory of air mobility warfare by the U.S. Command. Air mobility called for battalion-sized forces to be delivered, supplied and extracted from an area of action using helicopters. Since the heavy weapons of a normal combined-arms force could not follow, the infantry would be supported by coordinated close air support, artillery and aerial rocket fire, arranged from a distance and directed by local observers. The new tactics had been developed in the U.S. by the 11th Air Assault Division, which was renamed as the 1st Cavalry Division also known as “Air Cav” (Air Cavalry).

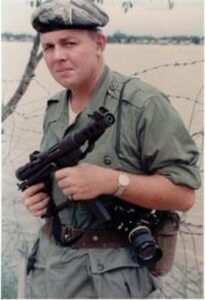

How these outnumbered Americans persevered – sacrificing themselves for their comrades and never giving up against great odds – creates a vivid portrait of war at its most devastating and inspiring. Joseph L. Galloway was the only journalist on the ground throughout the fighting.

Lt. General Harold G. Moore (ret.), a field commander at the time, and Galloway later interviewed hundreds of men who fought in the battle, including the North Vietnamese commanders. In 1992, Galloway and Moore wrote: “We Were Soldiers Once … and Young: Ia Drang – The Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam.” In 2002, a movie of the same name was released that graphically depicted this horrendous first battle. It is a film about uncommon valor and nobility under fire, loyalty among soldiers, and the heroism and sacrifice of men and women. In 2008, Galloway co-authored “We Are Soldiers Still: A Journey Back to the Battlefields of Vietnam.”

BRONZE STAR MEDAL CITATION:

“The United States of America.

To all who shall see these presents, greetings:This is to certify that the President of the United States of America by Executive Order, 24 August 1962, has awarded THE BRONZE STAR MEDAL with “V” device to JOSEPH L. GALLOWAY for heroism while accompanying the 7th Cavalry Regiment.

During the afternoon of 14 November 1965 a furious battle had been fought between the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, and the 66th Regiment of the Peoples Army of Vietnam. Mr. Galloway voluntarily boarded a helicopter which landed at night on a hazardous resupply run into an active combat situation where he was determined to report to the world details of the first major battle of the Vietnam War. Early on 15 November 1965 in the fury of the action, an American fighter bomber dropped two napalm bombs on the Battalion Command Post and Aid Station area gravely wounding two soldiers. Mr. Galloway and a medical aid man rose, braving enemy fire, and ran to the aid of the injured soldiers. The medical aid man was immediately shot and killed. With assistance from another man, Mr. Galloway carried one of the injured soldiers to the medical aid station. He remained on the ground throughout the grueling three-day battle, frequently under fire, until the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry was replaced by other forces of the 1st Cavalry Division.

Mr. Galloway’s valorous actions under enemy fire and his determination to get accurate, factual reports to the American people reflect great credit upon himself and American War Correspondents.

Given under my hand in the City of Washington this 8th day of January 1998

Earl M. Simms BG USA

The Adjutant General

Robert M. Walker, Acting”

Only a limited number of people are so noteworthy that their passing is memorialized in the New York Times or Washington Post obituaries. In the Washington Post obituary for Joe Galloway, the Battle of Ia Drang is recounted:

“In November 1965, journalist Joseph L. Galloway hitched a ride on an Army helicopter flying to the Ia Drang Valley, a rugged landscape of red dirt, brown elephant grass and truck-size termite mounds in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. Stepping off the chopper, he arrived at a battlefield that one Army pilot later called “hell on Earth, for a short period of time.”

Mr. Galloway, a 24-year-old reporter for United Press International, went on to witness and participate in the first major battle of the Vietnam War, in which an outmanned American battalion fought off three North Vietnamese army regiments while taking heavy casualties. He carried an M16 rifle alongside his notebook and cameras, and in the heat of battle, he charged into the fray to pull an Army private out of the flames of a napalm blast.

“At that time and that place, he was a soldier,” Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Kellogg said more than three decades later, when the Army awarded Mr. Galloway the Bronze Star Medal for his efforts to save an injured private. “He was a soldier in spirit, he was a soldier in actions and he was a soldier in deeds.”

Mr. Galloway later recounted the battle in a best-selling book, “We Were Soldiers Once …,” written with retired Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore, the U.S. battalion commander at Ia Drang. The book was adapted into a movie “We Were Soldiers” starring Mel Gibson as Moore and Barry Pepper as Mr. Galloway, and was acclaimed for its unflinching account of one of the war’s bloodiest battles.

“What I saw and wrote about broke my heart a thousand times, but it also gave me the best and most loyal friends of my life,” Mr. Galloway said in an interview with the Victoria Advocate, the Texas daily where he had once worked as a cub reporter. “The soldiers accepted me as one of them, and I can think of no higher honor.”

In all the confusion and chaos of battle, Joe Galloway knew what side of the fight he was on. He not only carried an M16 but went into harm’s way to save a fellow American. The 5 day battle at Ia Drang tested the metal of American airpower and the infantry. It also demonstrated the resolve and professionalism of the VPA.

Joe Galloway explained to Veterans Radio how a simple Texas boy ended up carrying a weapon in Vietnam:

“Lillie: When you first got to Vietnam, you were also carrying a weapon. How did that happen?

Joseph L. Galloway: Not when I first got there, but not long after, there were battalion commanders who would tell you straight up, “Look here, I don’t have the spare bodies to give you your personal bodyguard. You have to take care of yourself. If you are not carrying a weapon, you can’t march with my outfit.” Second of all, in spite of the fact that you carried a press card and it had real fine print on the back of it that said that you were to be treated with all the privileges afforded a Major in the US Army if you were captured by enemies of the United States. I didn’t recall if they were very kind to anyone of any rank if you fell into the hands of the enemies. Besides, they were shooting at me. I felt obliged, on occasion, to shoot back.

Lillie: After getting your first weapon, you went to Plei Me Camp, a Special Forces camp, and met up with Major Beckwith and got an even more powerful weapon. Can you tell us about that?

Joseph L. Galloway: It was the third week of October 1965 and Plei Me Camp was under siege by a regiment of the North Vietnamese and they were holding the camp hostage as dangling bait to draw the South Vietnamese armored column up the road to rescue them and they had another regiment standing by to ambush them. I wanted to get in there and the air space was closed. A couple of Huey helicopters had been shot down, a sky raider and a bomber, the place had those .51 caliber Chinese anti-aircraft machine guns on tripods and they were looking down our throats.

I was stomping up and down the flight line at Camp Holloway saying rude words and things and I ran across an old Texas Aggie helicopter pilot, a Huey pilot with the 119th helicopter company. He said, “What’s the matter, Joe?” I said, “Well, I’m trying to get into Plei Me Camp and there is no way to go.” He said, “Let me get the clipboard.” He took a look and said, “The reason you can’t get in there, is the air space is closed.” I said, “I know that, dummy, but I still want in there.” He said, “I wouldn’t mind taking a look, so I will give you a ride.” Rayburns flew me in there. He hit the ground. I took a picture. We were corkscrewing to avoid those machine guns and dropping in as fast as he could and I shot a picture out the open doorway. You can see the triangular-shaped camp filling that doorway in the picture. You can see the smoke from mortar bombs going off and that is where we were headed. He brought that thing in and I bailed out. We threw some wounded aboard and off he went.

This Master Sergeant Special Forces came up to me and said, “Sir, I don’t know who the heck you are, but Major Beckwith wants to speak to you right away.” I said, “Which one is he?” He said, “It’s that big guy over there jumping up and down on his hat.” He said a lot of rude words we can’t say on this network but he said, “Who are you?” I said, “I’m a reporter.” He said, “You know I need everything in the whole f*** world. I need medevac, I need food, I could use reinforcements, I need ammo. I need everything. I could use a bottle of Jim Bean and a box of cigars. And what has the Army and its wisdom sent me but a f*** reporter? I got to tell you, son, I have no vacancy for a reporter, but I’m in desperate need of a corner machine gunner, and you’re it!”

My mouth was hanging open by then. He hauled me over to a position and there was an air-cooled .30 caliber machine gun sitting there he showed me how to load it, how to clear a jam, and he gave me my instructions which were that I should shoot all the little brown men outside the wire but not the ones inside the wire, they belong to him. He said, “While you are at it, keep one eye always on that machine gun positioned down in the other corner of the camp because it’s manned by South Vietnamese CIDG, they’re infiltrated, I don’t trust them as far as I can throw them. If you see them turn that machine gun around, take them out.”

I spent three days and three nights with that machine gun, it was what you call “sporting times.” Finally, the armored column made it through the ambush, thanks to the 1st Cav hopscotching artillery batteries which were slung beneath Chinook helicopters. This was something new in this war and the North Vietnamese didn’t know about it when they snapped their ambush, they got hammered by precise artillery fire and they got hammered by a whole world of air.

Lillie: You did some more tours of Vietnam. After that first tour with LZ X-ray, were there other battles in that first tour that equaled it?

Joseph L. Galloway: None that ever equaled it, not in that tour or three other tours that I pulled in Vietnam, not in a half dozen other wars I’ve covered. That was a high watermark and it was the bloodiest battle of the Vietnam War. Right then, right there. 305 American boys were killed in that campaign. Hundreds and hundreds were wounded. Just a ferocious collision between the two finest light infantry outfits operating in the world. The North Vietnamese Army and the First Cavalry Division.

Joseph L. Galloway: My impression of the American soldier in Vietnam in 1965, 71, 73, of the American Soldier in the Gulf War, in Haiti, and two tours in Iraq, I have the highest respect for American Soldiers.

There is a difference between soldiers who fought in Vietnam in the draftee Army and those who fight today in Iraq and Afghanistan, the volunteer Army. These kids are more sophisticated. They are better educated, better trained, and certainly better armed.

Soldiering comes down to a matter of heart. That is unchanging. I think it has never changed from the first day a guy picked up a rock to defend his cave and his wife and kids, over 10,000 years ago. There is a sense about the soldier of selfless sacrifice. He isn’t in it for the glory. There is no glory in combat. There is no glory in war. It’s a hard, bloody task that will leave you carrying the burden of memories that no one should see, especially when you are 18 or 19 years old. The soldiers are the same. I’ve counted it a privilege to have been allowed to stand beside them then, to stand beside them today, and they are my brothers. What can I say?”

The casualties at Ia Drang were extensive. While both sides exaggerated death counts during the war, American casualties were 79 KIA at LZ X-Ray and the U.S. claimed that VPA count was 634 KIA. It was the intensity of the airstrikes and up-close killing on that hill that shocked the troops and the public when they ultimately read the truth.

The bravery and valor of men on the ground and in the air were recognized by the award of Medals of Honor, Distinguished Service Crosses, Silver Stars, and Bronze Stars. 2nd Lt. Walter Marm, Company A, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, received the Medal of Honor. Helicopter pilot Cpt. Ed Freeman and Maj. Bruce Crandall were each awarded the Medal of Honor. Freeman flew 14 flights and Crandall flew 22 volunteer flights in unarmed Hueys into LZ X-Ray while the enemy fire was so heavy that medical evacuation helicopters refused to approach. With each flight, Crandall and Freeman delivered much-needed water and ammunition and extracted wounded soldiers, saving countless lives.

Post-Vietnam

The shocking exposure to the firefights at LZ X-Ray was not Galloway’s last time in the war zone. He did four tours as a war correspondent in Vietnam. Between 1965 and the fall of Saigon in April 1975. He also covered the 1974 India-Pakistan War. Joe spent nearly 20 years as a senior editor and writer for U.S. News & World Report magazine.

Galloway retired as a weekly columnist for McClatchy Newspapers in January 2010, writing, “I have loved being a reporter; loved it when we got it right; understood it when we got it wrong… In the end, it all comes down to the people, both those you cover and those you work for, with or alongside for 50 years.”

In retirement, he then had time to work on books, movies, and other projects. Books such as, “Shock and Awe” (2017); “Home from the War” (2009); and “They Were Soldiers: The Sacrifice and Contribution of Our Vietnam Veterans” (2020).

Recalling a Defining Moment in Life

Joseph L. Galloway was a storyteller through and through. He spent a lifetime telling the stories of those that served. He was a guest on VeteransRadio.org on three occasions. From his interviews on the program in 2009, 2017, and 2020, here are Galloway’s recollections in his own words:

- When asked about his first 72 hours in the country, Galloway explained:

Joseph L. Galloway: I landed about two weeks after the Marines. The 1st Battalion, 9th Marines landed in Da Nang in March 1965. I landed in April coming from Tokyo. I sort of made a stop there for six months. I got to Saigon on a flight where my seatmate was a little Buddhist monk in an orange robe. The closer we got to Saigon, the more he was talking about sticking to me like glue. I wondered what the heck was going on. We landed and they told everyone to remain in their seats and a squad of white mice (the Saigon Police) got aboard and yanked that Buddhist monk out of his seat and dragged him down the aisle and down the stairs and he was one of those exiles who was trying to slip back in the country and failed utterly. They put him on the next plane back out. That was my arrival in Vietnam.

I reported to the old United Press International Bureau and had a day or two in Saigon to get my press card from MACV. Then I got on the mail run, C123 flight that ran from Saigon.

It took forever to get there but eventually, I made it to Da Nang and by then the Marines had taken over a former Merchant Marine brothel on the banks of the Da Nang river and turned it into a press center. I had a rented jeep and I lived in Da Nang for six or seven months. I would be up there for two or three months at a time before I would even get back to Saigon. I went on every operation the Marines made.

Joseph L. Galloway: “When I was younger, I had read the collected works of Ernie Pyle and WWII and I decided then, if there was a war during my generation, I wanted to cover it.

And if I covered it, I wanted to cover it like Pyle covered his generation. That’s upfront with the troops and that is precisely what I did. I didn’t like Saigon and I didn’t like the politics of the situation. I would get to Saigon once in a while and most of the 500+ accredited correspondents spent their time in Saigon. They went to the daily briefings, we called them the “5 o’clock follies,” and they would complain to me that they were lying to us. My answer was always the same, no one lies to you with the sound of the guns. You come out with me and people will tell you the truth.”

Joseph L. Galloway: “It was on the day I arrived. I got off that plane and a fellow ran up to me and said, “I am Raua, I work for UPI, there is big trouble, come with me.” I was carrying a Samsonite suitcase and still wearing chinos and loafers. I hadn’t even gotten a set of fatigues yet. I said, “What about my suitcase?” and he said something rude about it and threw it in the 8th Aerial Transport Squadron hooch at Da Nang and dragged me onto a C130 that was spinning up on the ramp. I didn’t know where I was going or what was going on. We made a short flight and we landed in a place called Quang Ngai City. We got off and it was like someone had stirred an anthill.

They were under serious attack and serious pressure in that area. It was an early attempt by the Viet Cong to cut the country in half. I got off and there was confusion all around, planes and choppers coming and going, people running around. This photographer ran off to a Marine H34, an old titanium magnesium-based helicopter, and he talked to the crew chief and then he waved at me and the next thing I know, I’m on this bird and we are flying out at a low level across the patties.

I still don’t know where I am and I still don’t know where I’m going. This helicopter finally comes upon a hill that rises out of the rice patties and it circled around this hill. I’m trying to look out the door and I can see there are a lot of people on top of this hill. We land there and they shut down, and there is dead silence. I got out of the bird and then I was told why they were giving us this ride. They needed our help.

A battalion of South Vietnamese had been overrun and killed to the last man and we were there to help them find and bring back the bodies of the two American advisors. They had only time to sort of scratch out a little body depression in the ground and every man was lying where he had made his last stand, hands out like he was holding a rifle but the rifle was gone. We went hole to hole until we found the two Americans and carried them back to the helicopter. It was a very sobering welcome to Vietnam.

Lillie: That was on your first day?

Galloway: Yeah.”

- Joseph L. Galloway worked on a project commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War and spoke to Veterans Radio’s founder and host Dale Throneberry, a helicopter pilot in Vietnam, about it in 2017.

Throneberry: Joe is currently working as a special consultant on the Vietnam War 50th Anniversary Project that’s run out of the Office of the Secretary Defense. He’s also served as a consultant on the Ken Burns’ production. He’s done a lot. He’s a veteran’s veteran and he’s never really been a veteran, except that he did get a Bronze Star for what he did in the Ia Drang Valley.

Galloway: “I first was asked by them to sit for an interview. It turned out to be 11 hours of interviews and two sessions in New York City six years ago. After the interviews, they asked that I come on as a permanent consultant. I’ve been helping out as best I could since then. Two years ago I went up to Ken’s house in New Hampshire and, with the other advisors on this project, sat down and rewatched the roughs. I thought it was so good then, I was saying go ahead and broadcast it now. Ken’s a perfectionist and they did it all exactly right and took their time and I’ve watched each of the episodes night by night like everybody else has and I’ve got to say that I think it was magnificent storytelling and history telling. Even if you count yourself an expert on Vietnam, if you served there, if you’ve read the books, still this 18 hours in 10 parts was great. I’m proud to have been associated with the production in even a small way.”

Galloway: “I would say that no matter what we did, we would not win that war. Even if we sent in a million troops instead of half a million, the Vietnamese were never going to quit. General Moore, my co-author and I sat down for three interviews with General Võ Nguyên Giá, the North Vietnamese commander. I said, “General, they say that you’ve send a million of your own countrymen to their deaths in this war.” He looked at me and said, “Yes, and I would have sent five million or ten million. We would have fought on for 10 years, 20 years, 50 years if that’s what it took to get the foreigners out of our country.”

I was left with no doubt that he would have done exactly that and we could still be there, we could still be fighting or rather our children and our grandchildren would still be fighting. What can I say? It broke my heart to watch this documentary night after night and see great young Americans who answered the country’s call, either they were drafted or they enlisted, and they were sent halfway around the world to fight other young men in a war in which we really had no place.”

- After Joseph L. Galloway co-authored a follow-up book, “We Are Soldiers Still: A Journey Back to the Battlefields of Vietnam,” he spoke with Veterans Radio for the last time in May 2020; fifteen months before his death.

Throneberry: Where did you come up with the idea to talk about the sacrifices and contributions of Vietnam Veterans?

Galloway: Marv Wolf and I have been friends for 55 years. When I first met him, he was a Spec 4 photographer in the 1st Cav Division Public Affairs Office at An Khe in 1965 and we’ve been friends ever since. He moved to North Carolina a couple of years ago, he lives about two hours drive from me and we got our heads together and it’s something both of us had been thinking about – and that is that so many Vietnam veterans came home to no welcome, no respect, the media, the movies portrayed Vietnam Veterans as losers and Lieutenant Dan and a lot of bullshit like that and it’s just wrong.

That’s not who I saw in four tours in Vietnam from the beginning of that war to the end of it. We wanted to focus on 48 Vietnam Veterans – not so much about the war they fought, but about the lives that they have lived and the good that they have done for their communities and our country since that war. They came home and did good stuff and there are some famous people and there are some people you’ve never heard of but should have. They are all successful and they are all giving individuals. And there ain’t a loser among them.

- A glimpse into Joseph L. Galloway’s personal life and humanity is displayed in this 2017 conversation:

Throneberry: I want to talk about your wire – tell me a little bit about her.

Galloway: Doc Gracie is a truly remarkable human being. The best thing that ever happened to me. They say third time’s the charm and she’s wife number three and we’ve been together… I met her 50 years ago in Indonesia, should have married her then, and kept track of her until about 30 years ago and saw her in D.C. Then she disappeared.

She turned up ten years ago and I said, “Where the hell have you been?” She said, “Well, I took my 8-year-old daughter and ran away and joined the circus.” Yes, she had signed on as a traveling nurse with Barnum & Bailey and a year later she and her little daughter were aerialists in the trapeze act in the Big Top. She did that for 10 years and then she came back and got her nurse practitioner degree and license and then she got a Ph.D. in public health and she turned back up.

I said, “You’re not getting away this time. I’m going to marry you.” She’s Singapore-Chinese, now an American citizen. She was the first cousin of the old Singapore Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, who founded modern Singapore and made it run like a Swiss watch… and she’s nobody to mess with. She still works every day at the Community Free Clinic here in Concord. She doctors people who have no insurance, people who are poor, people who are homeless, and a not inconsiderable number of homeless veterans who camp out in the woods behind the Harris Teeter grocery store. If they are too spooked to come to the clinic, she takes her black bag and goes out in the woods and treats them out there.

Throneberry: I wanted to bring her up because she was actually in Vietnam during the Tet Offensive.

Galloway: She was, indeed, and was working with the street kids and war orphans in Saigon and a relative had a big house in Chợ Lớn, the Chinese section of Saigon. That house was burned down, so she went through some tough times.

Throneberry: I wanted to get to that and how she continued on and just wanted to be a nurse and that’s what she’s doing forever.

Galloway: That’s what she’s been going forever and she’s going to keep doing it as long as she’s drawing a breath.

Throneberry: You’re lucky that you found her again.

Galloway: Absolutely. She says she’s going to get another 15 years out of me.”

Doc Gracie only got four more years with Joe when he passed in 2021. The measure of a man is the life he lived, the people he helped, and the body of work he left behind. Joe Galloway measures up in all regards. He proved himself in battle, in journalism and finally in his family life.

About James G. Fausone, Esq.

James G. Fausone, Esq. is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED