Operation Dewey Canyon

VIETNAM - HO CHI MINH TRAIL

C. Douglas Sterner

It was a heck of a way to fight a war, almost like the children’s game of hide and seek – only deadlier – and it wasn’t a game by any means.

Running almost the entire length of both North and South Vietnam was an enemy supply road, infamously known as the Ho Chi Minh trail. Stretching from the Communist capital in the north, this supply route funneled thousands of enemy soldiers and tons of weapons and supplies to the south, almost entirely within the protected confines of Laos and Cambodia. But for the aerial attack, the Ho Chi Minh trail was invincible. United States soldiers and Marines were not allowed to cross the borders.

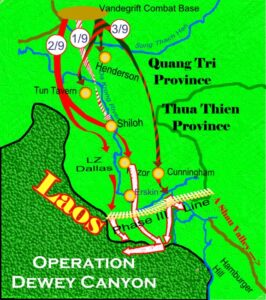

Lance Corporal Thomas Noonan did his best to ignore the mud as his company slowly moved down the side of the hillside. It was February 5th, and Operation Dewey Canyon was two weeks old. The men of the 9th Marines were moving into the A Shau Valley, and Company G, 2d Battalion, 9th Marines (2/9) was moving out of its location southeast of Vandergrift Combat Base as part of the incursion into A Shau. It was early in the monsoon season, so the progress of the Marines was hampered not only by the dense foliage but also by the intermittent rains and the slippery mud. Suddenly, bad went to worse as the lead element walked into the enemy.

From their concealed positions, the North Vietnamese opened fire, wounding four men. Further up the hill the rest of the Marines were stuck by the impossible terrain and the hail of enemy fire. No one could reach the wounded.

Lance Corporal Noonan was a rifleman in his company, despite an education that could have granted him an almost immediate commission when he joined the Corps. Now the 25-year old took upon himself the task of rescuing his brothers. Carefully he moved down the slippery slope, ever mindful of the heavy enemy presence. Nearing the wounded, he took cover behind some rocks to shout encouraging words to the wounded Marines, assuring them that help was on the way.

Alone, he raced across the fire-swept area, locating the most seriously wounded man and dragging him back to shelter. Enemy rounds whistled through the area, hitting Noonan and knocking him to the ground. Despite his own wounds, Lance Corporal Thomas Noonan got back up and resumed dragging the wounded marine towards the cover of the rocks from which he had earlier encouraged the men. Before reaching its shelter, the enemy fire reached out again, a rain of hot lead striking the young corporal’s body. Inspired by Noonan’s example, the rest of the platoon charged the enemy, pushing them back and reaching the wounded. All four survived. Noonan was the only casualty. He died; the collar of his wounded comrade’s fatigue shirt still grasped in his hands in a valiant attempt to save a friend. He was the first to earn a Medal of Honor in an operation that would test the courage of all the Marines of the 9th.

The commanding general of the 3d Marine Division, headquartered out of Da Nang, was Major General Raymond G. Davis. For Davis, this was his third war, having served in World War II and receiving the Medal of Honor for his heroism at the Chosen Reservoir in Korea. Davis referred to the 9th Marines as the “Mountain Regiment” and his “Strike Force Regiment”. As Operation Dewey Canyon began on January 22nd, General Davis had good reason to pay close attention to the efforts of his Marines. Among the men assigned to meet and defeat the enemy in their A Shau sanctuary was a young lieutenant in command of a rifle platoon. By a strange twist of fate that defied military policy prohibiting relatives from serving in the same war zone, Operation Dewey Canyon would send Davis’ son, Lieutenant Miles Davis, into harm’s way.

The first phase of Operation Dewey Canyon primarily involved the movement and positioning of air assets. Phase II, the movement of three battalions of the 9th Marines out of Vandergrift Combat Base began on January 31st. It was during this move to position the 9th Marines at the northern edge of A Shau that Lance Corporal Noonan died trying to save the life of his fellow Marines.

From January 31st until February 10th, 2/9 continued its movement south, flanked by 1/9 and 3/9. Colonel Robert Barrow, commander of the 9th Marine Regiment (who later became the 27th Commandant of the Marine Corps), coordinated the mission with support from American assets throughout I Corps. By February 10th the three battalions were poised and ready to enter Phase III, the incursion into A Shau. Along the way they had built numerous firebases with names like Henderson, Tun Tavern, Shiloh, Razor, and Cunningham, to provide artillery support and maintain supply routes.

The large movements of the three battalions demanded a regular and consistent resupply at Vandergrift Combat Base. On February 13th far to the north, a convoy was carrying supplies to Vandergrift when it was ambushed. In the heavy mortar and small arms fire that followed, the convoy security squad moved to engage the enemy. Marine Lance Corporal Thomas Elbert Creek dashed across the fire-swept area to take up a better position from which to attack the enemy when he was wounded. Almost as quickly as he fell, the enemy threw a grenade at his position. Nearby were others of his squad, men who were about to die. Ignoring his previous wounds, Lance Corporal Creek rolled on top of the grenade to absorb the blast, sparing the lives of his comrades at the expense of his own. Though not officially part of Operation Dewey Canyon, in his support role the 18-year old hero’s posthumous Medal of Honor must be counted with that of those who fought further south.

Even as Lance Corporal Creek lay dying in a gully northeast of Vandergrift, far to the south the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines were crossing the Da Krong River only 13 kilometers from Laos. Phase II of Operation Dewey Canyon was underway. The following morning the Marines of 1/9 and 2/9 began moving out of their firebases as well, heading southward and towards the North Vietnamese Base Area 611 that ran from the north boundary of A Shau and into Laos.

The move into A Shau was at once both miserable and dangerous. Triple-canopy jungle made movement difficult and two weeks of continuous fog and heavy monsoon rains removed any possibility of personal comfort and made resupply difficult. The enemy moved freely through the A Shau at night on roads they would carefully camouflage during the day with movable trees and shrubs ingeniously planted in containers. As they moved, the Marines were subjected to heavy artillery fire from NVA guns inside Laos. At night, more troops and weapons moved down the Ho Chi Minh trail. General Davis caused a slight stir on the home front when a newspaper reported a remark made in a personal conversation. “It makes me sick”, the 3rd Marine Division C.G. had said, “to sit on this hill and watch those 1,000 (enemy) trucks go down those roads in Laos, hauling ammunition down south to kill Americans with.”

Early in the third phase of the operation, General Davis flew out to meet with Colonel Barrow. Earlier that morning the General had begun receiving reports of enemy contact – “Kilo Company, firefight, 1 killed, 2 wounded.” An hour later Kilo Company was in contact again, more Marines killed, more wounded. Davis did his best to concentrate on the meeting at hand, all the while knowing that his son was a rifle platoon leader in Kilo Company. Even as he landed for his meeting with Colonel Barrow, some of the wounded were arriving – Lieutenant Miles Davis among them. The younger Davis would survive his wounds and subsequently would receive the Purple Heart Medal from his father.

Meanwhile, in the A Shau, other Marines struggled to stay alive and complete their mission. By February 20th the Marines had moved all the way to the Laotian border. As the enemy played their deadly game of hide-and-seek, raining death on young American Marines and then quickly scurrying across the border into the safety of Laos, Colonel Barrow had seen too many of his men die to the unfair advantage. “The political implications of going into Laos were pretty unimportant to me at that point”, he later stated.

The policy of US commanders had always been that units could enter Laos or Cambodia, only when American lives were endangered by enemy forces therein. (Usually, this applied to SAR (Search and Rescue) missions for down pilots or LRRP (long-range reconnaissance patrols). Colonel Barrow saw the danger his own men faced from within and, despite the very real possibility of sacrificing his distinguished military career, ordered Hotel Company, 2/9 to cross the border and set up ambush positions inside Laos. (This plan was approved by General Creighton Abrams, commander of all U.S. Forces in Vietnam – after the border crossing had already occurred.)

With elements of the 9th Marines now operating inside Laos, the other battalions moved out to take up positions along the border. On the morning of February 22nd, the 1st Battalion was in place on a ridge overlooking Laos. The Marines of 1/9 called themselves the Walking Dead. On this day, for one company in particular, the name would be all too real.

First Lieutenant Wesley Lee Fox was in command of Alpha Company, 1/9. He was a seasoned veteran, now in his 19th year in the Marine Corps. As a young Corporal, he had served in Korea, slowly working his way through the ranks to become a First Sergeant by 1966. The veteran leatherneck, now in his second war, had begun anew…working his way through the commissioned ranks. Fox had already completed a tour in Vietnam and recently had extended his combat tour.

As dawn broke on the forested hillside overlooking Laos, Alpha Company was sent out to look for and destroy a suspected enemy force operating in the region. Lieutenant Fox’s 3rd platoon had made contact with them the previous day, and now the Company was looking to finish the fight. In addition, First Battalion was low on water. A detail was dispatched to get resupply from a stream below, Alpha Company leading the way to provide security as Lieutenant Fox and his men searched for the enemy. As they reached the stream, the enemy appeared.

The NVA seemed to be everywhere, popping up out of hidden spider holes to rain devastating machinegun and small arms fire on Alpha Company, while enemy mortars fell on the embattled Marines. The suddenness and the ferocity of the attack caught the Marines by surprise, many falling wounded in the initial onslaught.

Quickly, Lieutenant Fox moved out, working his way through the heavy jungle overgrowth to gain a position where he could assess the situation and direct his platoon leaders. Deadly missiles struck the foliage and bamboo palms around him. Fox located a sniper’s position, quickly killing the enemy with his M-16 rifle before moving on.

As Fox deployed his platoons, two enemy mortar rounds landed in his position, killing his radiomen and air and artillery observers. Shrapnel struck the lieutenant in the shoulder but, despite the bleeding wounds, he grabbed both radios and continued to direct the movements of his Marines.

The lieutenant who led Fox’s 2nd platoon was seriously wounded, and Fox instructed his executive officer to take command of that platoon. When his platoon leader in the 3d platoon was killed, Fox quickly moved in to fill the void and take command. He personally destroyed one position while continuing to shout orders and give encouragement. Coolly he spoke into the radio to coordinate aerial and artillery support for his Marines. Among those working to defend these Marines on the Laotian borders was artillery officer Harvey “Barney” Barnum, who had earned the Medal of Honor three years earlier and returned, at his own request, for another Vietnam tour.

As the enemy fire continued unabated, the executive officer Fox had sent to 2nd Platoon was killed, and another of his lieutenants was wounded. Though wounded himself, Fox was the only officer in Alpha Company still capable of leading the resistance. This he did with calm professionalism, his Marines repulsing a final enemy assault during which the Company Commander was wounded a second time.

Heedless of his battered body, Fox began organizing his survivors to establish a defensive position. As corpsmen moved about to locate and treat the wounded, Fox refused aid, setting himself to the task that leadership demanded. By late afternoon, his Marines had secured their position, and Delta Company 2/9 arrived to relieve them. Ten of Fox’s brave Marines had died, of the 153 men who had joined him that morning in the patrol down from the ridge, only 66 were able to continue the mission the following day. Despite his wounds, and determined not to leave Alpha Company leaderless, Lieutenant Fox was among them.

For two weeks, Captain Dave Winecoff and Marines of Hotel Company operated in Laos, setting up ambush positions to strike back at an enemy that had never recognized the neutrality of Laos and had effectively used it to advantage against American soldiers and Marines. Five days after the border crossing, one patrol from Hotel 2/9 was moving down a road inside Laos when it was attacked by an NVA squad firing automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenades from the shelter of their fortified bunkers.

Two Marines fell very close to the enemy bunkers, wounded and trapped. Efforts by others in their patrol were met by heavy and sustained enemy fire. Twenty-one-year-old Marine Corporal William David Morgan slowly began working his way through the undergrowth to a position near the open road directly in front of the enemy position. Yelling encouragement to the wounded Marines, Morgan suddenly stood and rushed into the open roadway to single-handedly attack the enemy. Fully exposed to the fury of the enemy emplacement, his efforts drew an immediate and torrential rain of enemy fire. Corporal Morgan’s lifeless body fell to a heap in the middle of the roadway, but his valiant charge had distracted the enemy and drawn their fire long enough for the remaining men of the patrol to reach and rescue the wounded.

A year later Corporal Morgan’s family accepted his Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon during ceremonies at the White House. His date of heroism is listed as 25 February 1969, and the place of action is listed vaguely as “southeast of Vandegrift Combat Base, Quang Tri Province, Republic of Vietnam”. Indeed, he sacrificed his life southeast of Vandegrift – far to the southeast – far enough to be outside Quang Tri province and inside the borders of Laos.

Operation Dewey Canyon officially ended on 3 March 1969 when Hotel Company left Laos. In those 56 days, US Marines built more than 20 base camps and accounted for more than 2,000 enemy casualties. Dewey Canyon was different from other campaigns, however, in that the real goal had not been a combat mission to destroy the enemy, but a mission to take away his large cache of supplies being stockpiled in A Shau. During the period US Marines captured 1,200 enemy machineguns, 4,000 bicycle tires, 2,200 enemy rockets, and two big 122mm cannons. More than 500 tons of enemy ammunition was confiscated or destroyed, as well as more than 100 tons of rice stockpiled to feed the enemy troops. Much of the confiscated rice was subsequently donated to needy villages in the region.

The success of the mission was not without cost to the Marines of the Mountain Regiment either…130 young American boys killed in action, 932 wounded.

On the last official day of Operation Dewey Canyon, a reconnaissance company was returning to their base of operations out of Fire Support Base Cunningham when they were attacked. Private First-Class Alfred Mac Wilson took charge as acting squad leader of the rear squad, maneuvering his men to outflank the enemy.

When two men manning his own machinegun were wounded, Alfred Wilson and another Marine were rushing to man the gun themselves when an enemy soldier stepped from behind a tree to lob a grenade between the two men. Immediately, Corporal Wilson threw his own body over the grenade, dying beneath its lethal blast, to spare his comrade.

Hostilities did not end with the official conclusion of Dewey Canyon either. The Marines continued to hold their base camps in and around A Shau as the Mountain Regiment began their slow withdrawal. Two days after Alfred Wilson jumped on a grenade to spare his comrade, a similar engagement occurred at Fire Support Base Argonne near the DMZ, where Marines of the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division were lending their own support to Operation Dewey Canyon.

When the enemy made an early morning attack on the 12-man recon team’s position, Private First Class Fred Ostrom headed for a two-man position with his friend, PFC Robert Henry Jenkins Jr. An enemy grenade exploded as the men reached their position, blowing off part of Ostrom’s right hand and arm. As the wounded man sagged into his position, a second grenade was thrown directly into the emplacement. PFC Jenkins quickly pushed Ostrom aside, then covered his wounded friend with his own body. Jenkins’ shield of flesh and blood spared the life of his wounded friend, but at the cost of his own life.

Such was the courage of the Marines, from the experienced vets of other wars like General Davis, Colonel Barrow, and Lieutenant Fox, to the valiant young warriors fresh out of high school. They went, they did their job, and some came home. Valor abounded, many were the acts of heroism that went unrecognized – five Marines earned Medals of Honor – and only one, Lieutenant Wesley Fox survived to wear it.

He does so, humbly, in honor of all those valiant Marines who became a part of his own legacy in Operation Dewey Canyon

About C. Douglas Sterner

In 1998, C. Douglas Sterner launched the Home of Heroes website to document the citations and biographies of our Nation’s Medal of Honor recipients. His research led him to expand the site's mission to include other medal recipients that have been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, and others.

Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC took over the site in mid-2018. We are grateful for Doug's faithful management of the site and vow to maintain the site with the same integrity.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED