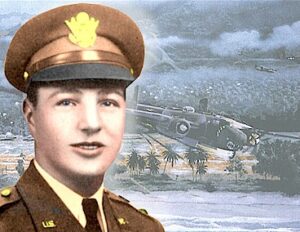

Ralph Cheli

Leadership By Example, Sacrifice & Design

In the summer of 1942, just six months after Pearl Harbor, despite Allied victories at Midway and in the Coral Sea, it appeared as if the battle to turn back Japanese aggression would be fought in Australia. From Tokyo to Borneo and eastward across New Guinea to the Marshall Islands, the Japanese ruled on land, at sea, and in the air.

In the summer of 1942, just six months after Pearl Harbor, despite Allied victories at Midway and in the Coral Sea, it appeared as if the battle to turn back Japanese aggression would be fought in Australia. From Tokyo to Borneo and eastward across New Guinea to the Marshall Islands, the Japanese ruled on land, at sea, and in the air.

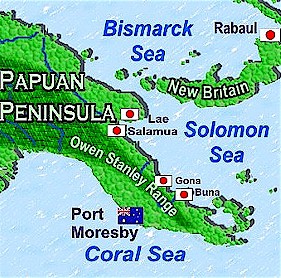

After the fall of the Philippine Islands, General Douglas MacArthur began mapping out his war strategy from his headquarters in the Australian city of Melbourne. The enemy was at his doorstep, and the only buffer between the Allied forces in Australia and the massive Japanese forces to the north was a small strip of land on the southeast coast of New Guinea called the Papuan Peninsula. There, a small but resolute group of Australian jungle fighters called "Diggers" clung tenuously to Port Moresby, the last vestige of freedom in the region.

New Guinea is the world's second-largest island. Stretching nearly 1,500 miles east to west between the South Pacific and the Coral Sea north of Australia. The half-million square mile land mass consists primarily of the primitive jungle. The topography, which includes the steep Owen Stanley Range that splits the north end of the Papuan Peninsula from the south, makes the prospect of organized troop movement nearly impossible. The hot, humid jungle climate with its wild denizens and deadly tropical diseases made the island itself more deadly than human foes.

The Japanese attempted conquest of the Papuan Peninsula with the landing of 3,000 troops at the important port of Lae on March 7, 1942, followed by an additional buildup of enemy forces at nearby Salamua. In May the Japanese tried to take Port Moresby with an amphibious assault from the south called "Operation Mo," and were turned back following the Battle of the Coral Sea.

On July 21 Japanese soldiers landed at Gona and Buna, directly opposite Port Moresby. The only thing separating the two opposing forces was the formidable Owen Stanley range. From these two bases, Japanese infantrymen made a daring effort to traverse the mountains via the Kokoda Trail, to attack Port Moresby by land. By August when U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, it looked as if the Japanese onslaught in New Guinea was unstoppable, and that it was only a matter of weeks before Australia, already subject to enemy bomber attacks, would be vulnerable to an amphibious assault as well.

On July 21 Japanese soldiers landed at Gona and Buna, directly opposite Port Moresby. The only thing separating the two opposing forces was the formidable Owen Stanley range. From these two bases, Japanese infantrymen made a daring effort to traverse the mountains via the Kokoda Trail, to attack Port Moresby by land. By August when U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, it looked as if the Japanese onslaught in New Guinea was unstoppable, and that it was only a matter of weeks before Australia, already subject to enemy bomber attacks, would be vulnerable to an amphibious assault as well.

Douglas MacArthur dispatched two of his generals to recon New Guinea and report back to him on conditions on the island, which was now thinly reinforced with small contingents of American infantrymen. The observations of Generals Pat Casey and Harold George were not encouraging. Reporting back to MacArthur in Brisbane, they advised the Allied commander and his staff that combat in the jungles of New Guinea was nearly impossible. The two men didn't see how human beings could live on the island of New Guinea, much less fight there.

When the matter had been discussed among the staff MacArthur rendered his decision. "We'll defend Australia in New Guinea," he announced to his surprised commanders. It was the last strategy most of them would have considered, or recommended, after hearing the reports from Casey and George.

"That," announced MacArthur, "is why we will do it. If it is the last thing YOU would expect me to do, it will also be the last thing the Japanese will expect me to do."

Indeed, after the end of World War II, one senior Japanese naval commander admitted that they did not think MacArthur would "establish himself in (New Guinea) because he did not have sufficient forces to maintain himself there." General Douglas MacArthur's campaign to return to the Philippine Islands by first wresting control of New Guinea and the Bismarck Sea from the Japanese was typically McArthuresque--do the unexpected--achieve the impossible.

In point of fact, in 1942 MacArthur did NOT have sufficient forces to defend Port Moresby, much less to drive the enemy out of the Papuan Peninsula. While enemy forces landed daily north of the Owen Stanley range, commanders back in the United States had made the war in Europe a priority while instructing MacArthur to do his best to simply delay Japanese expansion with a meager army and a rag-tag air force.

Ken's Men

The arrival of General George Kenney in August 1942 may well have been the turning point that vindicated MacArthur's ambitious plans for the Pacific war. With the dedicated leadership of Generals Kenneth Walker and Ennis Whitehead, the disorganized and badly demoralized patchwork of American pilots and ground crews in Australia were transformed under Kenney into a viable Air Force.

The arrival of General George Kenney in August 1942 may well have been the turning point that vindicated MacArthur's ambitious plans for the Pacific war. With the dedicated leadership of Generals Kenneth Walker and Ennis Whitehead, the disorganized and badly demoralized patchwork of American pilots and ground crews in Australia were transformed under Kenney into a viable Air Force.

Prior to Kenney's arrival, American pilots were sprinkled informally among varied R.A.F. air groups. They flew, and fought, under a confusing command structure that was spread between R.A.F. commanders and the Far East American Air Force Commander General George Brett. When Brett fell out of favor with MacArthur, air operations were micro-managed by MacArthur's Chief of Staff, General Richard Sutherland. Morale was low, spare parts were virtually non-existent, and military discipline was A.W.O.L. Upon his arrival in Australia to replace Brett, General Kenney described the Far East Air Force as, "the god-damnest mess you ever saw."

One of General Kenney's first actions upon assuming command was ordering an inventory of his available assets for the accomplishment of his mission. The initial report was encouraging. The Far East Air Force had:

- 245 American Fighter Aircraft

- 53 Light Bombers

- 70 Medium Bombers

- 62 Heavy Bombers

- 36 Transport Planes

- 51 Miscellaneous AirCraft

When the facts of that inventory were translated from paper to reality the news was not so good. Of the 245 fighters, 170 were either ready for salvage or were being overhauled. None of the light bombers were combat-ready, only half of the heavy bombers were fitted with guns and bomb racks, and one-third of the heavy bombers were being overhauled or rebuilt. The bottom line: of General Kenney's 517-airplane Air Force, only about 150 airplanes were capable of being sent into combat. The prospect of quickly supplementing this force with those airplanes "being overhauled or rebuilt" was of little comfort. The terms "overhauled" and "rebuilt," for the most part, meant that aged and combat-weary airplanes were being hastily refurbished by dedicated ground crews who managed to scrounge parts and improvise while patching torn wings and fuselages with the lids from the tin-cans that contained the daily rations.

A new structure and sense of identity came with the formal organization of the U.S. Fifth Air Force in  September. Kenney's first act was to get rid of the "deadwood", a move not aimed at men who had already struggled through months of warfare while feeling abandoned by their leaders and called upon to do the impossible with aircraft that were no longer fit to fly. General Kenney demanded leadership from those who had been placed in positions of responsibility. If his commanders couldn't lead by example they were "deadwood," and were quickly shipped home.

September. Kenney's first act was to get rid of the "deadwood", a move not aimed at men who had already struggled through months of warfare while feeling abandoned by their leaders and called upon to do the impossible with aircraft that were no longer fit to fly. General Kenney demanded leadership from those who had been placed in positions of responsibility. If his commanders couldn't lead by example they were "deadwood," and were quickly shipped home.

Under Kenney the Fifth Air Force quickly came together as a team, highly motivated behind men like Generals Ken Walker and Ennis Whitehead, both of whom flew combat missions with their aircrews--even against orders. Morale improved in the ranks, along with respect and even admiration for those who issued the orders that sent pilots and aircrews over hostile waters to engage a superior enemy force that had already honed its combat skills for several years.

Initially "Ken's Men" were spread between two fronts:

- Supporting the Marines struggling to sustain on Guadalcanal, and

- Reinforcing the beleaguered Allied forces still clinging to Port Moresby

Fifth Air Force Bomb Groups that had used Port Moresby only for a staging area for missions flown out of Australia began making the New Guinea airdromes their home in September, pushing MacArthur's bomber line 1,500 miles north of Brisbane. From there Kenney's intrepid pilots began conducting incredibly successful missions to destroy enemy shipping in the region, to bomb the myriad of enemy airbases scattered among the islands, and to support the ground movement of Allied infantry in New Guinea.

By November it was Ken's Men who held air superiority over New Guinea. The only remaining threat to Port Moresby was near-daily bombing/strafing runs by enemy aircraft dispatched from numerous fields north of the Owen Stanley Range.

Meanwhile, Ken's Men were making near-daily fighter/bomber missions of their own, continuing to attack enemy shipping in the Bismarck and Solomon Seas and destroying enemy airfields in the region. As the Fifth Air Force gained air superiority, it was possible for General Kenney to move more and more of his air assets from Australia to Port Moresby. This was critical since the Fifth Air Force fighters could not carry as much fuel as the large bombers. Missions launched from Port Moresby by medium or long-range bombers could now have fighter escorts all the way to most targets, thereby improving the chances of not only a successful mission but a successful return home.

The transformation of the Fifth Air Force, and the fact that in as little as 90 days it wrested control of much of the region from the seasoned Japanese air forces, can only be attributed to the leadership generated under General Kenney, along with the sheer guts and determination of the men who flew for him. That success is also a tribute to a quality long hailed by Americans— Ingenuity.

When General George Kenney came to Australia, he brought not only a badly needed sense of organization and leadership, he brought an open mind. One of Kenney's last official acts Stateside as commander of the Fourth Air Force had been the task of reprimanding (actually the investigating officer had recommended court-martial) of a young pilot who had been stunt-flying through San Francisco and looping the Golden Gate Bridge. Kenney's reaction in that confrontation gives considerable insight into the man's nature.

"Lieutenant," I said, "there is no need for me to tell you again that this is a serious matter. If you didn’t want to loop around that bridge or fly down Market Street, I wouldn't have you in my Air Force, but you are not going to do it anymore and I mean what I say."

"The door closed and I settled back in my chair thinking how wonderful it would be to be a kid in my twenties again, flying a "hot" airplane like the P-38, instead of being fifty-two and a general commanding a whole Air Force and riding herd on a lot of wonderful, enthusiastic, sparkling young pilots who had caught the same fever that I had twenty-five years before. I could still see those bridges over New York's East River, flashing by overhead on my first solo flight, back in the summer of 1917, and I could almost hear again the bawling out that I got from the colonel commanding the field a couple of hours after I landed. For a while, it looked as though I was going to be fired out of aviation and sent back to be drafted into the infantry...but the intervention of my civilian instructor...and the tolerance of my commanding officer had allowed me to stay in the flying game and grow up to be a general. I hoped in following his example (of leniency) I was also being a nice guy and that this towheaded youngster would also grow up to be a general someday."

When General Kenney departed for Australia, he took with him fifty hand-picked fighter pilots, including the young man he had so recently confronted. The "towheaded youngster" never did become a general, but Lieutenant Dick Bong did become America's greatest fighter ace of all time.

General Kenney respected the enthusiasm and exploratory nature of the young men who flew for him. While his older and seasoned commanders like General Walker and Whitehead brought the needed sense of tradition to his Air Force, Kenney remained willing to investigate new ideas to make his Air Force more successful.

Skip Bombing

Major William Benn was one such Fifth Air Force pilot with a new idea. Originally assigned to Australia as General Kenney's aide, Major Benn approached Kenney early in August with the idea of low-level skip bombing, a radical departure from the traditional Air Force doctrine of high-altitude attack. The R.A.F. had used skip bombing successfully and the U.S. Armament School at Elgin Air Field had tested the concept on a training level. Kenney became fascinated with the possibilities and gave Major Benn command of the B-17s of his 63rd Squadron to experiment with the method on a sand bar, and later on a wrecked ship in Port Moresby's harbor.

Major William Benn was one such Fifth Air Force pilot with a new idea. Originally assigned to Australia as General Kenney's aide, Major Benn approached Kenney early in August with the idea of low-level skip bombing, a radical departure from the traditional Air Force doctrine of high-altitude attack. The R.A.F. had used skip bombing successfully and the U.S. Armament School at Elgin Air Field had tested the concept on a training level. Kenney became fascinated with the possibilities and gave Major Benn command of the B-17s of his 63rd Squadron to experiment with the method on a sand bar, and later on a wrecked ship in Port Moresby's harbor.

The process was a hazardous one. Bomber pilots, instead of dropping their orbs safely from miles above enemy ships, would instead be required to fly directly into them at mast height (150 to 250 feet.) General Kenney noted;

"There might be something in dropping a bomb with a five-second delay fuze from level flight at an altitude of about fifty feet and a few hundred feet away from a vessel, with the idea of having the bomb skip along the water until it bumped into the side of the ship. In the few seconds remaining, the bomb should sink just about far enough so that when it went off it would blow the bottom out of the ship. In the meantime, the airplane would have hurdled the enemy vessel and would get far enough away so that it would not be vulnerable to the explosion."

Benn defined the process further:

"The sight used is an X on the co-pilot's window. The forward point of reference is the outline of the nose. Under these conditions in level flight at two hundred and fifty feet indicating approximately two hundred and twenty miles per hour, a bomb will fall from sixty to one hundred feet short of the vessel, skip into the air, and hit sixty to one hundred feet beyond. If perfect, the bomb will hit the side of the vessel and sink."

Skip bombing placed the bomber, pilot, and crew in great danger, demanding that the aircraft itself become the bombsight while flying directly into a curtain of fire from the target ship. Initial tests, however, proved it to be more accurate against ships than high-altitude bombing. Late in October, the process was tested on a real target during a night mission against Japanese shipping in Rabaul. Captain Ken McCullar made a direct hit on a Japanese destroyer with a bomb skipped from his B-17.

Major Benn continued to refine the practice of skip bombing, and General Kenney later noted, "Skip bombing became the standard, sure way of destroying shipping, not only in Bill's (Benn) bombardment squadron but throughout the Fifth Air Force." To minimize risk, however, until March of 1943 such missions were primarily done with the limited protection of the night.

In the meantime, the effectiveness of the Fifth Air Force's continuous and determined attacks on Japanese shipping was turning the tide of the war in the Pacific. Together with the U.S. Marine Corps' Cactus Air Force operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, the flow of enemy troops and supplies into the Solomon Islands was slowed drastically. By December little more than "mop-up" operations were required to obtain firm control of Guadalcanal.

Buna/Gona Campaign

In New Guinea, American and Australian forces hacked their way through dense jungle to fight their way to Buna, the enemy stronghold on the north side of the Papuan Peninsula. The conditions were exactly as Generals Casey and George had reported--primitive, deadly, impossible! When the initial advance stalled a livid MacArthur sent Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger to assume command of his I Corps along with the admonition: "Bob, take Buna or don't come back alive." Control of New Guinea was critical to both sides, and the commanders for both Allied and Japanese forces were responding with desperate measures--MacArthur to take Buna and Gona, General Hatazo Adachi to hold the two positions.

General Adachi had more than 7,500 combat-seasoned troops to defend the Buna/Gona region, but he knew that it might not be enough. During November and December, at least six attempts were made to reinforce Buna by sea. The weather became the chief adversary of the Fifth Air Force, and on December 1 four Japanese vessels managed to land 800 soldiers at Buna without incident. On December 9 Kenney's bombers were able to turn back six enemy destroyers headed for Buna, but the following week under cover of thick storm clouds, more enemy ships slipped in to unload troops. The following day more than 100 sorties were flown by American fighters and medium-range bombers against the newly arrived enemy forces. It was to be the last reinforcement of Buna that the Japanese could mount.

In the first week of January, the Buna-Gona region fell to General Eichelberger and his valiant I Corps. The cost was high but the stakes were higher. The 126th Infantry, for example, went into action on the Sanananda front with 1,199 men and officers. When this same unit was relieved on January 9, 1943, only 165 men and officers came out of the lines.

The campaign had taken a similarly high toll on the airmen who had supported the effort, including some of General Kenney's key leaders and innovators. General Kenneth Walker was lost on a January 5 mission over Rabaul, becoming the highest-ranking M.I.A. (Missing In Action) of World War II. Major Bill Benn was lost on January 18. Command in the Fifth Air Force was "Leadership by Example." General Kenney's officers didn't command their men into harm's way, they led them there. All too often, they died leading their men.

March 3, 1943

Major Ralph Cheli's eyes seemed to blur as he piloted his B-25 Mitchell over the vastness of the Bismarck Sea, hidden below him by an endless gray shroud of storm clouds. Somewhere beneath him and the trailing twelve bombers of his 405th Bomb Squadron was a parade of Japanese warships and troop transports. Finding them, and sending them to the ocean floor, was critical.

When the Buna-Gona region had fallen to Allied forces on Papua, the Japanese made the defense of Lae their primary concern. The heavily fortified port city was the gateway to the Bismarck Sea, and control of the Bismarck Sea meant ownership of the waters that stretched past Guam and the Philippine Islands, all the way to Tokyo.

Despite Allied possession of the Papuan Peninsula, the war for New Guinea was far from finished. Lae, scores of small islands in the region, and villages further west on New Guinea's northern coastline, still hid dozens of Japanese airfields. From them, regular raids were launched across the peninsula.

In February General Kenney had learned that the Japanese planned to reinforce Lae with the 51st Infantry Division. Intel suggested this massive force would be shipped out of Rabaul late in the month. They would depart Rabaul under the cover of the first major storm.

On March 1 the cloud cover over the Bismarck Sea parted long enough for a lone B-24 Liberator to note fourteen Japanese ships making their way across the waters below. Then the clouds masked the convoy again. While six Australian Bostons attacked the Lae aerodrome to keep Japanese fighters on the ground, seven B-17s scoured the northern coastline of New Britain Island in a search for the convoy. When darkness fell the American pilots resorted to flying fifty feet over the turbulent waters, lights on and dropping flares to attract attention, and, hopefully, enemy fire. If the enemy convoy saw the flight of Bombers, they didn't take the bait. The Flying Fortresses returned to Port Moresby at midnight, still frustrated in their search.

The following day the weather broke-up slightly, and shortly after dawn Lieutenant Archie Browning noted movement across the waves beneath his B-17 The Butcher Boy. Cheers erupted among Browning's crew as they scanned the massive movement across the sea, each man trying to count. There were at least fourteen enemy ships below, all steaming for Lae. Less than two hours later a wave of eight American Flying Fortresses came in at 6,500 feet to drop the first bombs in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. One of the largest of the enemy transports became the first victim, leaving 850 Japanese troops floundering in the water. Two destroyers moved into to rescue the drowning infantrymen and, under cover of darkness, to land them near Lae before returning to the convoy.

Other attacks were mounted, and there were other reports of hits and victories, but by nightfall, the weather had done its job of shielding most of the enemy force. Largely intact, the convoy continued on towards Lae.

Virtually every available fighter and bomber was launched on March 3 to find and attack the Japanese armada bound for New Guinea. Twelve B-25 Mitchell bombers trailed Major Cheli as he led his 405th Bomb Squadron northward on the mission that would ultimately, more than any other raid of the war, vindicate the ideas espoused by their bomber's namesake.

At 1000 hours Rear-Admiral Shofuku Kimura's armada, destined for New Guinea with its cargo of 7,000 Japanese soldiers, was in the midst of changing the watch when the alarm sounded. More than 100 American aircraft had located Kimura's convoy when it moved into the open waters of Huon Gulf, the home-stretch before Lae. Twelve Australian Beaufighters led the attack, screaming in on the enemy fleet at an altitude of 200 feet to rake the decks with the four cannon and six machine-guns mounted in their nose and wings. Mistaking the twin-engine fighters for torpedo bombers, Admiral Kimura ordered his ships to turn bow-on into the attack. It was a major blunder.

Moments later thirteen American B-17 bombers began unloading their deadly 1,000-pound orbs from high above. Japanese Zeroes rose to attack in defense of their ships. One Flying Fortress fell in flaming ruin while American P-38s from the 39th Squadron streaked in to intercept and engage the fighters. In the thirty minutes that followed Major George Prentice's airmen knocked down ten of enemy planes, while pilots of the 9th Squadron and gunners in the B-17s claimed ten more. (Further away at Finschhafen, a young American Ace named Dick Bong, flying in support of the overall mission, would claim his sixth victory.)

While the aerial dogfight raged, a short distance behind the Australian Beaufighters and the initial flight of Flying Fortresses, Major Ralph Cheli got an early preview of the deadly combat that lay before his squadron of B-25s. From miles out, he could see the near-misses of the bombs that fell from B-17s high above, and the smoking ruins of the enemy ships that had taken direct hits. With the enemy convoy now in his own sights, Cheli nosed his bomber downward to nearly wave-level.

Behind Cheli's formation, twelve B-25C1's from the 90th Squadron followed his lead. These bombers had been modified with extra guns for low-level strafing. Captain Jock Henebry, leading one flight from the 90th, recalled seeing all those ships and feeling "scared as hell" at the thought of flying right up to their sides at water level. Skip bombing had always been done at night when incoming airplanes could find at least a small element of safety in the darkness. Major Cheli was leading this force directly into the guns of the enemy ships in broad daylight.

Major Cheli made his run on the convoy, releasing his bombs in the face of a deadly fusillade from guns firing point-blank at his nose. Behind him the other twelve Mitchells of the 38th Bombardment Group released their own deadly explosives, coming in low and pulling upward only at the last minute in order to clear the masts of the enemy ships.

Behind Cheli's lead formation came the 90th Squadron, raking the enemy with their heavy guns and each dropping three or four bombs before breaking away. These, in turn, were followed by twelve A-20's of the 89th Bombardment Squadron and six B-25's of the 13th Bombardment Squadron. The forty-two American planes that had followed Cheli into the maelstrom left behind them two sinking destroyers and three sinking transports. During the pivotal Battle of the Bismarck Sea, 23-year-old Major Ralph Cheli had led the first daylight, low-level skip bombing mission of the Pacific war. That mission proved to be one of the most successful air-to-ship attacks in history.

Major Ralph Cheli, 5th US Army Air Force

Born in San Francisco, California, on October 29, 1919, Ralph Cheli's youth took him across the nation before his military service sent him across the globe. In February 1940, 19-year old Cheli enlisted in the Army as a flying cadet in New York City. He trained at Tulsa, Oklahoma, and at Randolph and Kelly Fields in Texas before earning his wings in November. He served assignments as a pilot with the 21st Squadron and then served with the 43rd Bomb Squadron flying B-24 Liberators out of MacDill Field, Florida, when World War II began. In the early months of 1942, he flew anti-submarine patrols in the Caribbean and was promoted to the first lieutenant.

In July 1942 Lieutenant Cheli was transferred to Barksdale Field, Louisiana, to serve as operations officer for the 405th Bomb Squadron, one of three remaining squadrons in the 38th Bombardment Group. (Two of the 38th Group's squadrons were sent to Hawaii earlier in the year and participated in the Battle of Midway. They did not subsequently rejoin the group.)

When Lieutenant Cheli joined the 38th BG, only the air echelon remained stateside. Ground crews had departed for Australia earlier in the year, while pilots and air-crews remained in Louisiana to train in their B-25 Mitchell bombers.

Even before Cheli joined the 405th Squadron in May, the B-25 Mitchell had a distinguished record of service in the Pacific. The twin-engine, medium-range bomber had been responsible for the first American victory during the famous Doolittle raid over Tokyo.

Originally designed for low-level bombing missions, the B-25 was smaller than the long-range B-24 or B-17 and had a range of only about 1,200 miles. Normally it carried a crew of five, half the number assigned to the larger bombers that had been built for the high-altitude bombardment of industrial plants and factories. Often forgotten among the great aircraft of World War II, the B-25 established an enviable record of service in China and North Africa. It was particularly well-suited for General George Kenney's low-level flight strategy in the Pacific air war.

When newly-promoted Captain, Ralph Cheli led the 405th Bomb Squadron to Brisbane, Australia, in August, the 405th was the first B-25 squadron to reach the combat theater in an over-water flight. That the 22-year-old pilot with less than three years in service would be given such responsibility is a testament to his leadership ability. Ralph Cheli was well respected and was considered one of the finest officers in the 38th Bomb Group.

The 405th Squadron, which called itself the Green Dragons, arrived in northern Australia on August 22. Captain Cheli flew his first combat mission three weeks later on September 15, a strike against Japanese installations at Buna on the northern Papuan coast. Thereafter the men of the 38th Bombardment Group flew regular missions against enemy airbases, oil production facilities, ground forces, and anything that moved on the water. Almost from the beginning, the primary tactic of their B-25 Mitchell bombers was tree-top level strafing of their targets prior to releasing the ton of bombs each aircraft could carry

Cheli's immediate superior, 38th BG commander Colonel Brian Shanty O'Neil, set a great example for his officers. Walter Krell, a pilot from the 22nd Bomb Group recalled:

"His (O'Neil's) stature as a brave man set him high among other brave men. He was in total command of himself, the men, the machine, and the situation. When a Group order was issued prohibiting squadron commanders from flying combat, Shanty would have none of it. As C.O. of the 38th Group, it was not uncommon for Shanty to go off in the lead plane, get back several hours later, and hop right back into the lead plane of the next flight.

Colonel O'Neil lead his men by example and demanded the same from his squadron leaders. In October the Green Dragons under the command of Captain Cheli relocated to Port Moresby for combat operations. In the six months that followed Cheli lead his men in more than 30 air missions. One month before his historic daylight, low-level skip bombing raid during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Ralph Cheli was promoted to major. This marked him one of the Army Air Force's youngest and fastest-rising commanders. Of Cheli, Walter Krell recalled:

"(22nd BG commander Dwight Divine) Divine used to wince when I sounded off about how squadron commanders should be the flyingest SOBs in the squadron. That's the way Shanty had it in the 38th. Cheli and Tanberg did more than their share.

The sad thing about Cheli was that he had said about two days before he got lost that he would be a colonel before he was 25 years old. I'd been at it almost a year by then and Cheli was still gung-ho fresh.

I remember thinking it was dangerous to talk. Little wonder, though, that I wanted to follow Shanty to an outfit that worked from top to bottom."

Lae: Doorway to the Philippine Islands

Within six months of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Philippine Islands had fallen and American forces were pushed all the way south to Australia to recoup. In the summer of 1942, all that stood between Australia and imminent invasion by Japanese forces was the Island of New Guinea.

By the fall MacArthur's forces were on the offensive, moving across the Coral Sea to push the encroaching enemy forces backward. MacArthur's strategy to return to the Philippines was to first cross the Owen Stanley Range to establish forward positions at Buna and Gona and then begin the long trek over the enemy-infested northern coast of New Guinea. When Buna and Gona fell in the opening days of 1943 it placed increasing importance on the Japanese-held port city at Lae. Lae was critical for both Allied war planners, as well as the Japanese high command. Lae was indeed the front door to the Pacific and the Philippine Islands.

The failed Japanese effort to reinforce Lae in the first days of March 1943 was a crushing defeat. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea not only resulted in the sinking of four, and possibly as many as eight, enemy battleships, but the loss of all eight transporters carrying the 7,000-man 51st Japanese Infantry Division to Lae. More than half of that ground force destined to battle for possession of Lae was lost at sea. Fewer than 2,500 Japanese soldiers were rescued and returned to Rabaul. Only the 800 or so men rescued after the first transport was sunk, soldiers which were landed by destroyers on the night of March 2-3, ever reached New Guinea. (Many of these were killed by strafing squadrons early the following morning while the major air-sea battle was being waged in the Huon Gulf.

The deadly disaster proved to the Japanese that Ken's Men now controlled the skies in the region and that further attempts to reinforce New Guinea by sea would be met with similar devastation. To adjust, the Japanese began building airfields further west on New Guinea's northern coastline, hidden in the dense jungle far enough from Allied forward bases to offer some safety, but close enough to continue harassment of American forces at Buna, Gona, and across the mountains at Port Moresby.

For the men of the Fifth Air Force, this shift meant fewer missions against enemy shipping and increased emphasis on finding the myriad of hidden enemy airfields. Every enemy plane destroyed on the ground meant one less enemy pilot to tangle within the sky. Each Nippon fighter or bomber burning on the ground also meant several fewer deadly machineguns to strafe Allied airfields or advancing American and Australian infantrymen. As they had been since the formation of the Fifth Air Force, Ken's Men were innovative and creative in developing the necessary tools of their trade to accomplish this mission.

Para-Frag Bombs

When Air Chief General Hap Arnold called George Kenney to Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1942 to ask him to transfer to Australia and fix the mess that was the Far East Air Force, Kenney made two special requests. One was for fifty P-38 fighter aircraft and pilots (including Lieutenant Bong) to fly them. The other was for a shipment of 3,000 parachute-fragmentation bombs. Kenney advised Arnold that if he was to assume command of the Pacific air operations, he wanted total air superiority--"air control so supreme that the birds have to wear Air Force insignia." This could only be achieved by the destruction of Japanese airplanes, either in the air or on the ground. The P-38s would knock them out of the air, the para-frag bombs would destroy them before they ever became airborne.

Para-frags were small, ten-kilogram (23-pound), explosives that could be hand-thrown from aircraft to slowly descend to earth and explode on impact. They could be very quickly scattered across a wide area from a low-flying B-25 Mitchell or A-10 Boston and would settle into the smallest opening behind the revetments enemy engineers had created to protect their planes while on the ground. Upon detonation, they spewed out nearly 2,000 shards of white-hot metal to tear through wings and fuselages, rupture gas tanks, and to set grounded planes on fire.

Five thousand of these para-frags had originally been manufactured in 1928 for shipment to Australia, but only 2,000 had been delivered. The 3,000 requested by General Kenney was the remainder of a weapon stockpile that more than a decade later, no one else seemed interested in. Ken's Men put them go great use with their innovative minds, coupled with the creative genius of an aircraft engineer the men of the Fifth Air Force called "Pappy."

Pappy Gunn

It is probably not over-simplification to note that Douglas MacArthur had the plan to defeat the Japanese and return to the Philippines, but that it was General George Kenney that made that dream possible. Similarly, the success of General Kenney and his courageous and innovative young airmen was possible thanks in no small measure to a 40-year old, retired Navy machinist's mate named Paul Irving Gunn. Because of his age, the beloved legend of the Pacific war was, however, simply known as Pappy.

Born in Arkansas, Paul Gunn joined the Navy at age 17 hoping to become a pilot. Lack of formal education, however, hampered his plans. Instead of flying, Gunn spent most of his Naval career teaching other men to fly. Subsequently retiring to the Philippine Islands with his wife to run a small inter-island airline, Pappy's exploits to ferry VIPs and other trapped Americans out of the Islands in the days before the Japanese gained full control were legendary.

Pappy was given the rank of Captain in the Far East Air Force and was working as an engineering and maintenance officer at Charters Towers, Australia, when General Kenny met him on August 5, shortly after the latter's arrival. Kenney quickly saw the potential in the man whose informal education was beyond equal. Pappy Gunn could do impossible things to aircraft, enabling them to do things previously deemed improbable.

Pappy is perhaps best remembered for his modifications to Fifth Air Force airplanes that made it possible for them to mount and fire more than a dozen 50-caliber machine guns, and for his innovations enabling them to carry extra fuel and extend their range of operations. But General Kenney's first assignment for Pappy centered on the arrival of his 3,000 para-frag bombs. General Kenney gave Pappy a two-week deadline to modify his A-20s to carry the small, parachute-deployed explosives. As he always did, Pappy came through. By fall para-frags were dropping on Rabaul, and elsewhere in New Guinea and the Pacific Islands.

The little 23-pound innovations proved to be worth their weight in blood!

In the spring of 1943, scores of small enemy airfields were springing up in the jungles around Lae. On a near-daily basis, Japanese Zeroes made the hop over the Owen Stanley range to harass the seven American airfields at Port Moresby or to try and intercept bombers over the Solomon and Bismarck Seas. On April 15 General MacArthur met with Admiral William Halsey, who was commanding the forces in the Solomon Islands. The two commanders met in Brisbane to plan and coordinate their next step. The plan they devised was labeled Cartwheel and called for their two separate forces to begin a near-simultaneous advance on Japanese positions.

Operation Cartwheel was launched on June 30 when Halsey landed the 43d Infantry Division on New Georgia Island, in what he estimated would be a two-week campaign to secure the island and control the Munda Airstrip. In fact, the heavy jungle and tenacious Japanese forces turned the campaign into a month-long battle throughout July, costing more than 1,000 American lives. In the last four days of July, with Halsey's battle-weary soldiers making their last desperate drive to take the Munda Air Field, three soldiers earned Medals of Honor, including a young Ohio National Guardsman named Rodger Young. Corporal Young died in his moment of valor but his name and the account of his deeds became the lyrics of one of the war's best-known ballads.

On the same day that the 43d Infantry landed at New Georgia Island, back on New Guinea a mixed Australian-American unit known as McKechnie Force landed at Nassau Bay near Salamaua, a scant sixty miles from Lae. Desperate jungle fighting followed, but in the two weeks that followed the McKechnie Force moved half-way to Lae. The Fifth Air Force flew repeatedly in support of that operation and General Kenney's B-25s were the chief work-horses.

Meanwhile, Kenney's heavy bombers and fighters were busy preventing any Japanese re-supply for the embattled forces at Lae. They also worked hard at keeping enemy aircraft on the ground, and those Jap fighters and bombers that did get in the air were quickly shot down. On July 26 thirty-five B-25s and eighteen B-24s were bombing enemy positions in Salamua and Lae when sixteen enemy fighters tried to intervene. Eight escorting P-38s promptly shot down eleven of the enemy. Four of them fell to the guns a Lieutenant Richard Bong, doubling his previous one-day record and earning him the Distinguished Service Cross.

Two days later, while escorting bombers in an assault on enemy shipping north of New Britain Island, the same P-38s shot down eight of fifteen enemy fighters. Dick Bong got his sixteenth victory to tie Captain Tom Lynch as the leading Army Air Force ace in the Pacific. Unfortunately for Bong, his airplane was damaged and he spent the next month on R & R in Australia.

General Kenney's fighter pilots were doing a great job of knocking down Jap planes, but as the situation at Lae became more desperate for the Japanese, it seemed more and more enemy planes were rushing to the rescue. General Kenney suspected that many of these were coming from airfields further west, hidden in and around Wewak. There were, in fact, four new airfields under construction at Awar, Boram, Wewak, and Dagua. Determined to fight an offensive war, Kenney knew it was time to move further west. For the Major Ralph Cheli and the pilots of the B-25s based at Port Moresby, it was to be their deepest penetration of enemy territory to date.

For Major Ralph Cheli, who had now logged 39 combat missions, it would also be the most dangerous.

August 16-17, 1943: Midnight

Fifty long-range bombers from Port Moresby slipped through the darkness high over the Owen Stanley range under the cover of night. Their destination--WEWAK! They comprised nearly 50% of the bomber force available to General Enis Whitehead, commander of the First Air Task Force assigned to all air operations in northeastern New Guinea. The size of the attacking force was evidence of the importance General Kenney placed on wreaking destruction on the airfields near Wewak. It was the largest mission since the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

The Japanese were caught completely unawares. Only a few of the B-17s had been forced by mechanical problems to turn back, and the bulk of the bombing force arrived over their target 560 miles from Port Moresby in the pre-dawn darkness. For two hours bombs rained down on all four airdromes, while anxious gunners on the ground filled the air with flak and the beams of their searchlights. Three heavy bombers were shot down but reconnaissance photos taken the next day showed the mission had been highly successful. At least 18 enemy airplanes had been destroyed on the ground.

The Japanese were not the only ones surprised by the first Wewak mission. The same photographs that gave evidence of the wrecked or burning carcasses of dozen-and-a-half enemy fighters, revealed as many as 200 perfectly good enemy fighters still on the ground. General Kenney had suspected the enemy had been moving large numbers of airplanes into the region but had not expected so many. In Fact, in the previous days, the entire Japanese Fourth Air Army and its headquarters had relocated to Wewak.

The Wewak first raid had been so successful and had been conducted with such limited casualties, only because the enemy had not anticipated an assault so deep into their own back yard. General Whitehead decided to strike again and quickly before the First Air Army could recover and mount a more vigorous defense. Even while the early-morning photos of that first raid were being reviewed back at Port Moresby, the second wave of bombers was crossing the Owen Stanley Range escorted by P-38 fighters.

Weather, however, intervened this time. Both B-25 squadrons from Port Moresby encountered heavy rains and impenetrable clouds. Only three of the bombers reached the area to scatter their para-frag bombs over the airstrip at Dagua. Those three determined pilots destroyed at least seventeen more aircraft on the ground and knocked down one of the enemy fighters that rose to defend the field.

Meanwhile, two squadrons from the 3rd Attack Group based out of the airfield at Dobodura, on the north side of the Papuan Peninsula, managed to navigate their way through the low clouds to strafe and para-frag both Wewak and Boram airfields.

"It was too much to ask after the heavy bombers had made their attack in the dark, that we would catch the Japs at Boram completely off guard," recalled Major Donald Hall who led the bombers from his 8th Squadron into Borman. "Yet that is exactly what happened."

"Before we were within effective range, we threw in a few shots to make them duck. We waited a few seconds and then cut loose again. A Betty bomber blew up on the runway. From then on, we had our gun switches down the raking plane after plane. The Jap airplanes were lined wing tip to wing tip the whole length of the runway. Several fuel trucks were parked alongside airplanes. Crews were busy. In the revetment area, a few airplanes were being loaded with bombs.

"The surprise was complete. Not an AA gun was fired. Not a plane got off the ground to intercept us. A fellow dream of a situation like that, but never expects to see it. We let go of our parachute bombs, in clusters of three, one after another. They drifted lazily down like a cloud of snowballs."

Captain Hall's squadron reported fifteen enemy aircraft destroyed on the ground at Boram. When the 3rd Attack Group's 13th Squadron hit Wewak, the results were even more incredible. They reported 70 - 80 enemy planes destroyed or damaged where they sat on the ground. "The reason all the planes were assembled there (Wewak)," later stated Colonel Koji Tanaka, a staff officer from Rabaul who was on the ground at Wewak on August 17 while the para-frags were falling, "is that we thought we were out of your (American) fighter range."

Twice-burned, the Japanese First Air Army would not be caught unawares again.

Back at Port Moresby Major Ralph Cheli was frustrated with the fact that weather had prevented his own squadron of Green Dragons, as well as most of the thirteen bombers from the Wolf Pack (71st Squadron) from reaching their targets. He was determined that, if given another chance, he would make it count. The opportunity came the following morning.

August 18, 1943

Fifty-three B-25 Mitchell bombers took off on the morning of August 18 for another crack at the enemy airfields surrounding Wewak. The weather remained a problem with heavy clouds and pelting rains. Major Ralph Cheli strained to lead his formation of Green Dragons north, up over 15,000-foot peaks, and then down closer to sea level as the formation neared the target area. Only half the formation remained; more than two dozen B-25s had been forced to turn back home.

Visibility was down to two miles but Ralph Cheli continued determinedly to navigate towards his assigned target at Dagua. Beside him, co-pilot Don Yancy kept track of the instruments and coordinated with the navigator, First Lieutenant Vincent Raney. Standing ready at their guns were Sergeants Raymond Warren and Clinton Murphree, completing the standard 5-man crew for a B-25. On this mission, there was a passenger. Captain John H. Massie, an observer with the Royal Australian Air Force, was along for the ride--and the battle. No one doubted that this time the enemy would NOT be caught unawares.

Ahead of the low-level bombers and high above the clouds, Colonel Art Rogers of the 90th squadron lead what remained of his own force of heavy bombers for the first strike. Anti-aircraft fire filled the sky long before the 26 heavies opened their doors to drop their bombs. The airfield was hidden by the low-lying blanket of clouds, but Rogers instructed his bombardier to do his best. He refused to return home without leaving something behind.

By the time Cheli's squadron was diving for their low-level strafing run the enemy was fully alert. Scores of Zeroes and Oscars abandoned the pursuit of the now retreating heavy bombers to concentrate on turning back the inbound Mitchells. At least ten Japanese fighters concentrated on the lead bomber in the formation, the shark-toothed B-25 flown by Major Ralph Cheli.

The escorting P-38s zoomed in to intercept but not before a stream of machine-gun bullets ripped into Major Cheli's airplane. Two miles from the target, fire was streaming from his right engine. Cheli was low, too low to safely bail out of the dying airplane. There was still time to pull up, to break formation, and gain altitude for the altitude necessary for a parachute evacuation. Cheli knew that as the flight leader, however, such a diversion by the lead bomber would shred the integrity of the whole flight which is now on its final approach.

Flames streaming from his airplane, Cheli held his dive. He came in low over the airfield at Dagua through a veritable curtain of anti-aircraft and machine gunfire. Below Cheli could see a string of parked Japanese fighters. His crew let loose with their machine guns, stitching them from end to end, while the remainder of his squadron followed him in to strafe and drop their para-frags. It was the most successful attack of the day.

Behind Major Cheli the airstrip at Dagua lay in ruin, the flames and explosions masked only by the flames streaming behind his own right engine. Major Cheli had led by example, taking the necessary risks to guide his men over their target and demonstrating his own willingness to sacrifice for the sake of the mission. His task finished; it was time to turn the reins over to someone else.

Cheli radioed his wingman and advised him to assume command of the flight while he tried to ditch in the water. The Green Dragons headed for home while a bevy of P-38s tangled with enemy fighters to cover their withdrawal. Behind them, they left the falling bomber of their commander.

Despite the great success of the mission over Dagua, the mood back at Port Moresby was somber. Ralph Cheli had been well-loved and highly respected, and every man in the squadron understood well that in their most recent mission he had exhibited great courage and leadership. When Major Cheli was submitted for the Medal of Honor, hope remained that he would emerge from the jungle after weeks of escape and evasion, to personally accept it.

When the medal was actually presented on October 28, no word had been heard regarding the fate of Ralph Cheli. Some of his squadron mates believed he had crashed into the sea; others thought their last glimpse of his aircraft had been to see it crash in flames. Hope was revived a few months later when a Japanese radio broadcast announced that Cheli and some members of his crew were being held as prisoners of war.

Only years later did the fate of Major Cheli and his crew come to light. The intrepid pilot, according to post-war reports, had managed to ditch his burning B-25 a few hundred yards offshore. Co-pilot Don Yancy and Captain Massie, the Australian observer, did not survive the crash. Cheli, badly burned, and his two gunners were picked up by the Japanese and taken to Dagua Airfield where they were interrogated by Captain Shigeki Namba of the 59th Sentai, who was credited with shooting them down. Then the prisoners were taken to prison camps in Rabaul, a place from which more than one American P.O.W. mysteriously disappeared.

The commander of the infamous Rabaul prison camps later claimed that many of these interred Americans had been sent by ship to Japan and that the ship had been bombed and sunk by aircraft of the Fifth Air Force. It was an unbelievable irony to think that Major Ralph Cheli and other of Ken's Men who had fallen into enemy hands, would ultimately be killed by their own comrades.

Among those interred at Rabaul was Captain Harl Pease, the first American Airman (after Jimmy Doolittle) to earn the Medal of Honor. Presumed killed in the crash of his B-17 on the opening day of the Guadalcanal campaign, post-war evidence indicated that Pease was actually murdered in captivity on October 8, 1942. Similar fates awaited Major Cheli and his gunners.

Based upon reports of those who survived the prison camps at Rabaul it is believed that one of Cheli's two gunners died of wounds sustained in the crash near Dagua and that the other was executed. These same reports indicated that though injured and badly burned, Major Ralph Cheli resisted interrogation and, as the senior American in captivity at the time, set an inspirational example to the other prisoners.

More than five years after World War II ended a mass grave was uncovered containing the remains of American prisoners executed early in March 1944. Like the mass grave found in the summer of 1950 near Rabaul's Matupi Volcano, the bodies showed evidence of their fate. Colonel Horton of the Imperial War Graves Commission said of that site:

"There is evidence to show that some of the men suffered execution at the hands of the Japanese as their limbs were bound with wire. Some of the bodies show signs of terrible mistreatment before death...Records show that the Japanese commander at Rabaul formerly stated that these men had been transferred to Japan on a destroyer which was later sunk. The statement of the Japanese commander is now proved to be untrue and steps have been taken by flight Lieutenant Rundle (RAAF) to have the Commander detained as a war criminal."

What is believed to be Major Cheli's remains were exhumed, along with the bodies of the other Allied prisoners executed with him. All were interred with full military honors in a mass grave at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri. Ralph Cheli who had been born in San Francisco, joined the Army Air Force in New York City, and then took his brand of valiant leadership halfway around the world, finally came home to the American heartland.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED