Raymond Wilkins

U.S. Raid on Rabaul Demoralizing to Japs

American Airmen Pitted Finest Offensive Weapon

Against Nips to Win Important Victory

By Lee Van Atta

International News Service (November 2, 1943)

ABOARD AN AMERICAN MITCHELL BOMBER EN ROUTE FROM RABAUL

Less than an hour ago American airmen pitted their finest offensive weapon against Nippon's most formidable defensive weapons. The Americans won the round in the most brutal aerial battering ever dealt with Japanese shipping.

For 25 Minutes the United States Mitchell bombers fought Japanese Zeros, flak ships, and land and sea anti-aircraft batteries to win their way to the assigned target. For another 30 minutes, they waged unceasing combat with what seemed unending streams of Zero and Messerschmitt fighters to reach home base.

The craft of this correspondent returned looking like a sieve.

The American craft attacked and destroyed almost all their objectives in the most demanding mission ever assigned to youthful United States bombardment and fighter pilots. In the grueling man-made hell, they destroyed or damaged over 94,000 tons of enemy shipping in Simpson Harbor.

It is almost impossible to analyze every thought and impression which flowed through the mind of any single man who witnessed the assault in those harrowing minutes which seemed like an eternity. But the general impression is that Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, could never have looked like Simpson anchorage today. Everywhere ships lay mortally wounded as the American raiders soared from their objectives. Everywhere there were pyramids of flame and crumbling, searing hunks of steel.

Capt. Richard Ellis, of Laurel, Del., veteran of 65 strafing missions against the foe and youngest command pilot in the southwest Pacific war theater, accounted for two vessels destroyed before the eyes of this correspondent. The ships were knocked out by a technique of attack a few men have ever witnessed.

WHOLE SKY ABLAZE

Bombs exploded and mingled with anti-aircraft bursts until it seemed that the whole sky was ablaze. At least four large Jap cruisers maneuvered in the bay and fired ..........

July 29, 1942

Seven aging U.S. Army A-24 dive bombers nosed neatly down into formation on the north side of New Guinea's Owen Stanley Range to break out of the heavy clouds. Ahead of them sparkled the blue-green waters of the Solomon Sea, while unseen in the dense jungle below, determined Australian Diggers fought for survival.

From his position as flight leader, Captain Floyd Buck Rogers scanned the clearing skies for any sign of the American P-39s that had been tasked with covering his seven strafer/bombers on today's mission. Somehow, in the clouds that covered the high mountains that split the Papuan peninsula, Major Tommy Lynch's fighter escort had become separated from the A-24 flight. It was time to make a critical decision.

Captain Rogers was commander of the 8th Squadron of the 3d Bombardment Group and had been well briefed on his target. A Japanese convoy had been sighted moving towards Buna to reinforce the enemy garrison that was already dealing death to the valiant but battle-weary Australian forces. To prevent these additional Japanese infantrymen from landing, Rogers had been ordered to take his eight A-24s, the last serviceable such aircraft in New Guinea, to intercept the convoy.

One of the eight had been forced to return home shortly after take-off, leaving only seven dive bombers to rendezvous with their fighter escort from the 35th Squadron. It was not unusual. The few American aircraft still flying in the Southwest Pacific were all showing the strain of relentless days of combat against an overwhelming and well-supplied enemy air force. Battle damage alone made it all too common for any flight to be quickly pared-down, more as a result of equipment failure than as a result of enemy combat. Matters were even worse for the men who flew A-24s.

The A-24 Dauntless was the Army Air Force's version of the Navy's SBD (Slow but Deadly), a dive bomber with lethal capabilities but a very slow airspeed and limited range. The Dauntless was lightly armed and carried a two-man crew: pilot and gunner, the latter defending his aircraft by manning a 30-caliber machine gun from a standing position behind the pilot.

The A-24 Dauntless was the Army Air Force's version of the Navy's SBD (Slow but Deadly), a dive bomber with lethal capabilities but a very slow airspeed and limited range. The Dauntless was lightly armed and carried a two-man crew: pilot and gunner, the latter defending his aircraft by manning a 30-caliber machine gun from a standing position behind the pilot.

Originally developed as a counterpart to Germany's Stuka dive-bombers for service in Europe, ironically 54 of the initial 78 A-24s were sent to fight Japanese shipping in the Pacific instead. By the summer of 1942 the slow-moving, lightly armed, 2-man dive bombers were both obsolete and nearly extinct.

Without protective fighter cover, Captain Roger's formation would be at the mercy of enemy Zeros. The squadron commander had every reason, and every right, to abort and return to Port Moresby for the sake of the thirteen men flying with him. When weighed against the cost for the men in the jungle below him if the enemy troop convoy proceeds unmolested, it presented the veteran officer with a difficult decision. Such is the burden of command.

In the distance fifty miles from Buna, small blotches came into focus across the swells of the Solomon Sea. The enemy convoy, the target for the mission, quickly morphed from a distant speck on the water into a distinguishable convoy of six troop transports and two escorting warships. Captain Rogers made his decision and wagged his wings to signal his following pilots to prepare for battle.

Diving at near water-level into the enemy guns, Captain Rogers felt his own airplane begin to shudder when his gunner, Sergeant Robert Nichols, opened up with the 30-caliber machine guns from his position behind the pilot. Two dozen Japanese Zeros of the Tainan Kokutani tore through the 8th Squadron formation like sharks in a frenzy, chewing the old A-24s into shreds. In a flash of fire Captain Rogers' lead dive bomber rolled over and plunged into the sea. He and Sergeant Nichols were the first casualties in what would become the darkest day in 8th Squadron history.

Heedless of the fusillade reaching out for them from the enemy ships below, or the Zeros that swarmed in to devour them from above, the six surviving pilots pushed the attack. On Captain Rogers wing an A-24 dove on a 6000-ton vessel and scored a direct hit with one 500-pound bomb, destroying the first element of the advancing armada. The American pilot, his bomb rack now empty, turned towards shore in a running battle for the clouds and safety.

First Lieutenant Virgil Schwab dove on another vessel and felt his dive-bomber coming apart as, no longer capable of flight, it careened into the sea to forever claim his body and that of Sergeant Philip Childs, his gunner. Two more A-24s erupted and Lieutenants Robert Cassels and Claude Dean went down along with their gunners, Sergeants Loree LeBoeuf and Alan LaRocque.

In mere seconds Lieutenant John Hill had witnessed more than half of the flight going down in flames. Then his own Dauntless shook beneath a hail of incoming enemy fire. Ignoring the danger Hill dove on an enemy ship. Machine gun bullets from the ships below and angry Zeros above tore through metal and flesh, and behind him, he heard a cry of pain from his own gunner, Ralph Sam. The young sergeant slumped to the floor of his battle station, his right hand and arm nearly severed. Sergeant Sam's blood-splattered the fuselage as Lieutenant Hill released his bombs and then climbed quickly to clear the enemy mast and turn towards the distant coast of New Guinea.

Behind Hill, Lieutenant Joseph Parker released his bomb while Sergeant Franklyn Hoppe fought furiously for survival as his pilot finished the mission and likewise turned to race for home. Seasoned Japanese pilots in nimble Zeros flashed by, machine guns lancing the withdrawing three A-24s as they fought to avenge the damaged ships and one destroyed by Captain Rogers' wingman. Behind Lieutenant Hill, Sergeant Sam found the strength to pull himself back up to his gun, firing back at the attackers with his unwounded left hand. The race, and the running battle, continued for miles. Even when the 30-caliber gun behind Lieutenant Hill fell silent, all its ammunition expended, the Jap pilots kept coming. He's mortally wounded but determined gunner refused to give up, pulling his .45 pistol with his left hand and standing at his station to empty it at the enemy fighters.

The pilot of the Dauntless that had destroyed the first ship while flying wing for Captain Rogers raced for a rain cloud. His bullet-riddled A-24 fought for air to climb inland and over the Owen Stanley Range. His young enlisted gunner fought furiously, desperate to defend his own aircraft while simultaneously hoping against hope that the other two surviving A-24s would reach that same small screen of safety. The mist at the outer edges of the cloud began to fog his vision, but not before he saw Lieutenant Parker and his gunner going down in flames while another bevy of enemy fighters converged on Lieutenant Hill and his now-silent gunner. And then the looming rain cloud masked all signs of battle, leaving only one Dauntless to continue its desperate struggle to remain airborne long enough to get home.

Of the seven aircraft that had crossed the Owen Stanley range less than an hour earlier on a mission to turn back the enemy convoy, only one badly damaged Dauntless returned to Port Moresby. When at last it landed there was no celebration. Of fourteen men who began that fateful mission, Lieutenant Raymond Wilkins and his gunner Sergeant Al Clark were the only survivors.

Raymond Wilkins

Raymond Wilkins

While many accounts of the July 29 mission note that Lieutenant Wilkins and Sergeant Al Clark were the only survivors, in fact, Lieutenant Hill managed to nurse his damaged airplane to a landing at Milne Bay. His valiant gunner, who had remained at his post with only one hand until his ammunition was expended and then drew his pistol to continue his defiant defense, died of his wounds three days after the mission. Lieutenant Hill survived the war, only to be tragically killed along with his wife in an automobile accident. Both are buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Raymond Harrell Wilkins, known to his friends throughout his life as "Wilkie" or simply "Ray", was born in Portsmouth, Virginia, on September 28, 1917. Two years later he moved with his mother and brother, William S. Wilkins, III, to Columbia (Tyrrell County), North Carolina where he grew up and gained early-life experiences that shaped him as an immaculate, dedicated, and highly motivated member of what would become known as The Greatest Generation.

After graduating from Columbia High School Wilkie attended the University of North Carolina for two years, and then enlisted in the U.S. Army Signal Corps in 1936. Military service for the bright, clean-cut young man was almost a foregone conclusion--his step-father was himself a career military man.

Wilkie served four years in various duties as a private at Langley, VA, and then at Chanute Field, IL. His sights, however, were on West Point. With his athletic physique, personal discipline, and quick mind, Wilkie epitomized the young academy cadets that graduated with the gold bars of a second lieutenant after four years of study. Wilkins passed all of the entrance tests for admission to West Point but then was rejected for slight occlusion of his otherwise perfect teeth.

Disappointed but determined to excel, Wilkie attended the Air Corps Technical School and was promoted to Corporal upon graduation in February 1940. Seven months later he earned the stripes of a staff sergeant and began instructing in radio at Chanute Field. The following year, in March, he began flight training at Parks Air College in East St. Louis. Additional training followed at Randolph and Kelly Fields in Texas.

On October 31, 1941, Raymond Wilkins received his wings and the gold bars of a second lieutenant, graduating with Class of 41-H. Years later his hometown's monthly newspaper would recall, "The boy we all knew and loved, grew quickly into manhood and into efficiency as a member of the air force." That same story, written six months after Wilkins' death, recalled Raymond as a young man who was "amiable and reserved in nature. He always scored the highest goals among his fellow teammates. This was not only true while he was among us but continued with him in all his activities.

On October 31, 1941, Raymond Wilkins received his wings and the gold bars of a second lieutenant, graduating with Class of 41-H. Years later his hometown's monthly newspaper would recall, "The boy we all knew and loved, grew quickly into manhood and into efficiency as a member of the air force." That same story, written six months after Wilkins' death, recalled Raymond as a young man who was "amiable and reserved in nature. He always scored the highest goals among his fellow teammates. This was not only true while he was among us but continued with him in all his activities.

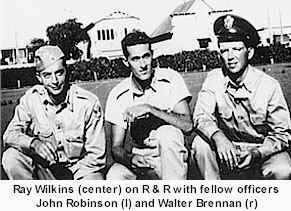

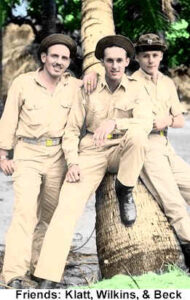

One of Wilkie's close friends and classmates was William Beck. The two men would see combat together in the pacific less than six months after graduation. In a recent interview, Mr. Beck recalled, "Ray was a perfect officer, clean-cut, smart, and a good pilot. He was determined to be the best leader he could be, and was eager to serve his country." Indeed, immediately upon earning his gold bar and pilot's rating, Second Lieutenant Raymond Wilkins requested foreign duty and was assigned to the 27th Bombardment Squadron in the Philippine Islands.

The record is unclear when and where Lieutenant Wilkins joined the 27th. The squadron had been formed early in 1940 from a Cadre pulled from the 3d Bomb Group. They began a long convoy under Colonel John Davies to their assigned duty station in the Philippine Islands on November 2, 1941, and arrived late in the month. Their dive bombers, making the trip in a separate convoy, had not arrived by the time the Japanese attacked the Philippines ten hours after Pearl Harbor, leaving the frustrated airmen little more to do in defense than shoot back at the attacking enemy with their pistols.

Lieutenant Bill Beck believes his friend may have been part of the same convoy that was taking him across the equator aboard the SS Willard A. Holbrook the day before World War II began. Called the Pensacola Convoy, the string of seven transport and cargo vessels escorted by the heavy cruiser USS Pensacola and submarine chaser Niagara departed San Francisco one week after President Roosevelt authorized Operation Plum to reinforce the Philippines on November 14, 1941.

Though the United States was at peace when the Pensacola Convoy departed Pearl Harbor en route to the Philippine Islands on November 30, the prospects for war were evident. The seven transports were crammed with 4,600 National Guardsmen including the 148th Idaho and 147th South Dakota Artillery units and their 75mm guns. Also being dispatched to reinforce the Philippines was a number of young airmen, 52 Douglas A-24 Dauntless dive bombers, and 18 Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks.

Early on the morning of December 8 (December 7th at Pearl Harbor due to the convoy's position west of the International Date Line), the speakers on the Holbrook announced the sad news that Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japanese. Before nightfall, the news only got worse. The young men being sent to augment the defense of the Philippines learned that General MacArthur's Far East Air Force had also been attacked, its airfields bombed, and most of its airplanes destroyed.

Thereafter the men in the Pensacola Convoy were ordered to wear life jackets at all times and to carry full canteens of water. Paint and brushes were issued and quickly the red, white, and blue hull of the Holebrook, formerly a commercial cruise ship, was converted to battleship gray. Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., the convoy became the subject of debate.

Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, head of the Navy's War Plans Division, urged the President to send the convoy back to Pearl Harbor to reinforce the garrison that had been bombed into ruin. Army War Plans Division Chief General Leonard Gerow suggested that the troops be sent back to the United States to marshal a homeland defense. General George C. Marshall prevailed upon the President to maintain the integrity of the convoy's mission of reinforcing MacArthur. On December 10 the President issued his orders, concurring with General Marshall ordering the convoy to sail south of the Philippines to debark in Australia.

On December 22 the Pensacola Convoy steamed into Brisbane Harbor. On that same day, Colonel Big Jim Davies and 20 pilots of the 27th Bomb Group arrived at Darwin from the Philippines to claim their aircraft, hoping to return with them to defend Manila. Instead, Colonel Davies and his men were diverted to Java where they fought valiantly but hopelessly to turn back the enemy's advance. It would be in fact, two years before they could return to Manila for, on that same day, Japanese ground forces landed at Lingayen Gulf just north of the Bataan Peninsula. For Lieutenants Wilkins and Beck, the war had moved far south of the Philippines to the Solomon Sea and the heavily jungled island of New Guinea. It would be a war of sacrifice and death. Together with air legends like Big Jim Davies and Pappy Gunn, they would become:

The 3d Bomb Group

The U.S. Army Air Force's 3d Bomb Group (Light), based out of Savannah, Georgia, at the time Pearl Harbor was attacked, traced its lineage all the way back to World War I. As an air group, it was initially organized under the name "Army Surveillance Group" on July 1, 1919, and re-named the "1st Surveillance Group" a month later. Its component squadrons were veterans of combat in France where they had established a solid record of combat service. Most had served as observation aircraft on low-level missions, though they had also engaged in both bombardment and pursuit combat.

The U.S. Army Air Force's 3d Bomb Group (Light), based out of Savannah, Georgia, at the time Pearl Harbor was attacked, traced its lineage all the way back to World War I. As an air group, it was initially organized under the name "Army Surveillance Group" on July 1, 1919, and re-named the "1st Surveillance Group" a month later. Its component squadrons were veterans of combat in France where they had established a solid record of combat service. Most had served as observation aircraft on low-level missions, though they had also engaged in both bombardment and pursuit combat.

• The 8th Aero Squadron had been the first to fly DeHavilland DH-4s, often called Flying Coffins but also known as Liberty planes for their new Liberty engines. Five years after the war ended the 8th adopted its official logo based upon this designation, consisting of an eagle clutching the famous Liberty Bell, and all this superimposed upon a target.

• The 90th Aero Squadron, known as The Dicemen for insignia featuring a pair of dice displaying a lucky "7", flew a variety of aircraft in World War I including Sopwith 1s, Salmson 2s, and even the newer Spad XIs. The squadron's missions were frequently low-level reconnaissance forays into enemy territory.

• The 104th Aero (Observation) Squadron, which was later consolidated with the 13th and re-designated the 13th Attack Squadron, flew Spads in World War I and adopted insignia depicting a skeleton with a bloody scythe. They became known as The Devil's Own Grim Reapers.

Despite a primary mission of low-level reconnaissance, observation, and aerial photography, the original squadrons that became the 3d Bombardment Group saw considerable combat action in the air. The 8th squadron was credited with eight aerial victories in World War I, the 90th with fourteen, and the 104th with four. (At the time the Group was established in 1919 there was a fourth squadron, the 12th, which was subsequently replaced by the 26th Squadron.)

Early post-war missions for the 1st Surveillance Group consisted of patrolling the nation's coast and borders. In 1921 the pilots in their DH-4s began intensive observation flights of the Texas/Mexico border. Such low-level specialties attracted the attention of General Billy Mitchell who saw in the group the potential for low-level strafing support of ground troops. He also noted the potential for dive-bombing, and pilots and planes of the 1st Surveillance Group played an important role in the late-1921 experiments off the Virginia coast that proved airpower would soon achieve preeminence over naval warfare.

Perhaps as a direct result of the Mitchell tests, in 1921 the 1st Surveillance Group was re-designated the 3d Attack Group and adopted a crest featuring Maltese Crosses to depict its component squadrons' aerial victories in World War I. The Group's motto: "Non-Solum Armis" (Not by Arms Alone), noted its important role in observation and reconnaissance. The green cactus on the crest symbolized the Group's post-war role patrolling the tense desert border between Texas and Mexico in defense of the homeland.

Between the world wars, the 3d Attack Group flew nearly every airplane developed and performed a variety of missions. On September 4, 1922, a young 90th Squadron pilot who had participated in the Mitchell experiment the previous year, took off from Pablo Beach, Florida, in his DH-4 sporting the logo of the Group's Dice Men. Twenty-two hours later Lieutenant Jimmy Doolittle landed at San Diego, California, becoming the first airman in history to cross the United States in a single day.

Between the world wars, the 3d Attack Group flew nearly every airplane developed and performed a variety of missions. On September 4, 1922, a young 90th Squadron pilot who had participated in the Mitchell experiment the previous year, took off from Pablo Beach, Florida, in his DH-4 sporting the logo of the Group's Dice Men. Twenty-two hours later Lieutenant Jimmy Doolittle landed at San Diego, California, becoming the first airman in history to cross the United States in a single day.

In a 1924 pairing of America's combat air force, the 3d Attack Group was reduced to two squadrons, the 8th, and the 90th. Five years later the 13th was reactivated. In the decade of service that followed, a period marked by training and experimentation critical to the development of airpower, the 3rd Attack Group became the rootstock for U.S. Army Air Corps low-level bombing and strafing tactics. In 1939 it was again re-designated, this time as the 3d Bombardment Group (Light). The 3rd seemed not to suffer from an identity crisis as a result of four different titles in twenty years. By now most of the pilots of all three squadrons, as well as the newly assigned 89th Squadron, had adopted the nickname of the 13th. As a Group, they were becoming known as The Grim Reapers.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, the Army Air Force stripped the veteran 3d Bomb Group of all officers above the rank of the first lieutenant, dispatching them to train the new recruits this new world war would require. The Group's A-20 combat planes were crated for shipment and one month later the Group, pared down to 17 officers and 800 enlisted men, sailed for Australia on the SS Ancon. The Group commander was First Lieutenant Robert Strickland, the highest-ranking officer remaining.

The 3d Bomb Group was one of the first air-combat units deployed in World War II, arriving in Australia on February 25, 1942. On March 10 the Grim Reapers moved to Charters Towers, 90 miles inland on Australia's northeast coast. The unit was told that they would soon receive a shipment of new A-20 dive bombers, but at the moment Lieutenant Strickland had very few pilots, no airplanes, and four squadrons that basically existed in name only.

Shortly after the arrival of the 3rd Bomb Group Colonel Big Jim Davies arrived at Charters Towers with 42 officers and 62 enlisted men--all that remained of the 27th Bomb Group. These men were the pilots and crew that left the Philippines in December to get aircraft, men that had arrived in the theater on the Pensacola Convoy. With these new planes, they hoped to return to defend their comrades. That return was halted at Java by the advancing Japanese, and by March little remained at Luzon for them to defend. The pilots, including Lieutenant Wilkins, along with eighteen A-24 Dauntless SBDs, were assigned to the 8th Squadron under command of the 27th Group survivor Captain Floyd Buck Rogers.

Due to his senior rank, Big Jim Davies assumed command of the 3d Bomb Group while Lieutenant Strickland became his Executive Officer. For Davies, it was something of a reunion. He had served as a pilot in the 3rd Bomb Group in the late 1930s, as had some of the other arriving 27th BG pilots. These were men who had been pulled from the group for duty in the Philippines the previous November. Also joining Davies at Charters Towers was a retired, enlisted Naval pilot who had received an Army commission shortly after the war began. He was a man who would become legendary in the Pacific, Captain Paul Irving Pappy Gunn. Pappy Gunn will long be remembered as the man who could work design miracles in any existing airplane in the Pacific, but in March 1942 the only existing aircraft in the 3d Bomb Group arsenal were the eighteen old A-24 Dauntlesses. The promised inventory of new A-20 attack bombers had yet to arrive. What Pappy Gunn did in late March to obtain the needed aircraft is a legend all its own.

Due to his senior rank, Big Jim Davies assumed command of the 3d Bomb Group while Lieutenant Strickland became his Executive Officer. For Davies, it was something of a reunion. He had served as a pilot in the 3rd Bomb Group in the late 1930s, as had some of the other arriving 27th BG pilots. These were men who had been pulled from the group for duty in the Philippines the previous November. Also joining Davies at Charters Towers was a retired, enlisted Naval pilot who had received an Army commission shortly after the war began. He was a man who would become legendary in the Pacific, Captain Paul Irving Pappy Gunn. Pappy Gunn will long be remembered as the man who could work design miracles in any existing airplane in the Pacific, but in March 1942 the only existing aircraft in the 3d Bomb Group arsenal were the eighteen old A-24 Dauntlesses. The promised inventory of new A-20 attack bombers had yet to arrive. What Pappy Gunn did in late March to obtain the needed aircraft is a legend all its own.

As with any legend, details have been changed and embellished in the retelling. The facts are, that a group of B-25 Mitchell Bombers ordered by the Dutch Air Force arrived in Australia in March. They had not gone unnoticed by Pappy. In his book The Grim Reapers, Lawrence Cortisi recounts what happened next:

On 27 March, a few days after Davis took over the Reapers, Gunn came into Big Jim's office and grinned. "Johnny, there's a couple dozen B-25s at Batchelor Field* in Melbourne."

Davis was surprised and asked if the executive officer had heard anything. Strickland shook his head. He had not heard of any aircraft reaching Australia for consignment to the 3rd Bomb Group. Davis then turned to Gunn with a frown."They aren't exactly ours," Gunn said. "I think they've been allocated to the Dutch Air Force, but from what I hear, they'll never use them because they have no pilots. The planes are just sitting there, and we've got a war to fight. Why don't we go down and get them."?

Davies grinned. "You mean steal them?"

"They said our planes were on the way," Gunn shrugged. "Who's to say those Mitchells aren't ours?"

*This may have been an error in Cortisi's account, as Batchelor Field was near Darwin, and there is no such record at Melbourne."

Pappy Gunn did indeed fly a contingent of 3d Bomb Group pilots in his C-47, either to Bachelor Field to pick up two dozen Dutch B-25s, or to Archerfield near Brisbane to pick up eighteen crated Mitchells. The newly arrived bombers were indeed the property of the Netherlands Air Force, which in fact no longer had piloted to fly them. Whether appropriated by Pappy, "With all of the aplomb of a second-story bandit and a river-boat gambler" as described by General William Webster (USAF/Ret), or willingly bequeathed to the 3d Bomb Group by the Dutch, Big Jim Davies pilots, at last, had airplanes. The legend of how the Grim Reapers "stole" their bombers from the Dutch is an interesting story, well worth reading despite its discrepancies and obvious embellishments. Indeed, Pappy got his planes, sans bombsights, which he returned two days later to get (according to some written reports at gunpoint.)

The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle, though most men who knew Pappy Gunn can easily imagine him doing exactly what the legendary accounts detail. At any rate, at least fifteen B-25s were obtained from the Dutch and assigned to the 13th and 90th Squadrons at Charters Towers. Pappy promised to have them combat-ready within two days.

On April 5, eleven days before Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and his sixteen Mitchell bombers took off from the USS Hornet near the Japanese coast, pilots of the 3d Bomb Group flew the first B-25 mission of the war. It was a largely uneventful attack on Japanese airfields at Gasmata on the south coast of New Britain Island, but for the Grim Reapers, it marked the opening of their war in their questionably appropriated B-25 bombers. In the years that followed, they would turn those Mitchells into dive-bombers scarcely recognizable by their manufacturer, and re-define the term "low-level attack."

Four days before the Gasmata raid Lieutenant Bob Ruegg led six A-24s of the 8th squadron in the first combat mission of the 3rd BG. The target for the day was the Lae Airdrome, but the port city was fogged in and the flight instead dropped five bombs over Salamaua. The first of repeated assaults on Lae did not occur until April 7 when eight Dauntless dive bombers, escorted by six RAAF Kittyhawks, bombed the airfield. That flight was led by 8th BG commanding officer Captain Floyd Rogers. His wingman was Lieutenant Raymond Wilkins. It was the young pilots' first combat mission.

April 7, 1942, was also the day the Grim Reapers suffered their first combat casualties. In the mission over Lae Lieutenant Henry Swartz and his gunner Sergeant, J. Stephenson was shot down. Three months later Buck Rogers was killed in a fateful July 29 mission. When the last bombing attack on Lae was mounted by 8th Squadron B-25Ds more than a year later on September 13, 1943, the mission was led by Captain Raymond Wilkins. He was, by then, the only pilot remaining from the first Lae mission.

At one o'clock in the morning on April 11, Big Jim Davies and Pappy Gunn led ten of their B-25s from the 13th and 90th Squadrons in a 1,600-mile flight back to the Philippines. All of the pilots and co-pilots were volunteers; ten of the twenty were former officers in the 27th Bomb Group who were returning with supplies and, hopefully, reinforcements for their beleaguered comrades who had been left behind. Sadly, the Royce Mission, named for its commander Brigadier General Ralph Royce, was too late. Two days before their departure General King had been forced to surrender his command at Bataan.

For three days Colonel Davies and his B-25s flew missions out of Mindanao, south of Luzon, while three B-17s from the 19th Bomb Group struck enemy targets near Manila. One of the Flying Fortresses was destroyed, the other two badly damaged, and the Japanese advance continued. At midnight on April 13, the two remaining B-17s and nine of the ten B-25s left Mindanao to return to Australia. Each was filled to capacity in a futile evacuation attempt, including one bomber that ferried out PT Boat Commander John Bulkeley. Bulkeley was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own heroic actions in the early days of the war, and the daring leadership he had displayed when he ferried Douglas MacArthur safely out of Corregidor.

For their role in the Royce Mission, the 3d Bomb Group was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation and Big Jim Davies was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. There was little joy in the small success of that last effort to defend the Philippines. Left behind at the mercy of an enemy who knew no mercy were more than 400 airmen of the old 27th Bomb Group. They were stranded with thousands of beleaguered American foot-soldiers and sailors, and a small contingent of Army nurses. Many would be lost in the Bataan Death March; others would vanish over the four years of war that followed. Few would ever be heard from again.

Also left behind was Captain Paul I. Pappy Gunn. For two frantic days, his crew worked to replace his shot-up, long-range fuel tanks with two tanks from a destroyed B-18. When his Mitchell landed in Australia on April 16 it was fitting--the last American bomber out of the Philippine Islands was flown by Paul I. Pappy Gunn. Left behind in Manila along with the thousands who couldn't be rescued were his wife and children.

New Guinea

Charters Towers was home for the 3rd Bomb Group, and from there the 89th Squadron operated as a maintenance echelon while awaiting the arrival of promised A-20s. Meanwhile, the 8th Squadron with its A-24s was moved to Port Moresby on the south coast of Papua, New Guinea, in late March. From there they began launching the squadron's first missions beginning on April 1. At the time Japanese troops were landing en mass on the north side of the peninsula, and regular raids were mounted against both airfields and ground forces on the north side of the Owen Stanley Range.

Charters Towers was home for the 3rd Bomb Group, and from there the 89th Squadron operated as a maintenance echelon while awaiting the arrival of promised A-20s. Meanwhile, the 8th Squadron with its A-24s was moved to Port Moresby on the south coast of Papua, New Guinea, in late March. From there they began launching the squadron's first missions beginning on April 1. At the time Japanese troops were landing en mass on the north side of the peninsula, and regular raids were mounted against both airfields and ground forces on the north side of the Owen Stanley Range.

The slow SDBs often flew into enemy territory with fighter protection from the RAAF's No. 75 Squadron, but the valiant Australian pilots were also vastly outnumbered and their Kittyhawks were old and battle-damaged. On April 11 as the 3rd Bomb Group's B-25s were flying into Mindanao on the Royce Mission, dive-bombers of the 8th Squadron were again attacking Lea led by 27th Group veteran Captain Bob Ruegg. Lieutenant Gus Kitchens and his gunner Sergeant George Kehoe never returned and the casualties continued to mount.

From April to July Captain Rogers repeatedly led his brave men in their aging Dauntless bombers over the mountains and into harm's way. His frequent wingman was Lieutenant Wilkins, who admired his squadron commander. The declassified official history of the 8th Squadron notes:

"2nd Lt. Wilkins' schooling made him an able and cool, yet determined and eager pilot and forceful combat leader. (He) came under "Buck" Rogers, in the first half of 1942, when the 8th Squadron traded blows in A-24s against infinitely superior Jap forces. His training in Squadron administration and in fair but firm dealing with his men and officers, was by Captain Virgil Schwab, Operations Officer during the same period. Many times, later in his friendly and instructive talks with younger pilots, Wilkie would refer to his two ideals,

• Bible-reading but hard-riding "Buck" Rogers as the best combat leader he had ever known, and

• Captain Schwab, as the absolute prototype of the idea army officer, always on the job, conversant with every department, with his primary thought the welfare of his men whom he inspired and led because they wanted to be as he was."

On July 29 Lieutenant Wilkins flew his last mission with both Captain Rogers and Lieutenant Schwab (both men were posthumously promoted, accounting for the difference in rank in some historical documents.) Neither man returned and for Ray Wilkins, it was a crushing moment--his two most highly-regarded role models lost in the Solomon Sea or the jungles of New Guinea. It is interesting that the 8th Squadron history goes on to note:

"When he (Lieutenant Wilkins) had matured and become C.O. of the 8th, Wilkie was the incarnation of the best in these two men he had strived to emulate. He was at times hard but always fair. He earned and held the respect of all his enlisted men and officers in a manner rare in the Air Corps."

Fifth Air Force

The tragic July 29 mission was the breaking point for the 8th Squadron, now reduced to fewer than ten pilots. Colonel Davies submitted Lieutenant Wilkins, the last survivor who had somehow managed to bring his badly damaged plane home, for the Distinguished Service Cross. (The award was still pending at the end of the war and there is no record of it being subsequently awarded.) For his actions in combat from April to the end of July Wilkie was awarded the Silver Star. It was little consolation.

Big Jim Davies ordered what remained of the 8th Squadron back to Charters Towers and, their heavy losses bearing mute testament to the inadequacies of the A-24 ended the Army use of the Dauntless. William Webster remembers the mood when he arrived to join the 8th Squadron shortly thereafter:

"The 8th Squadron Officers Mess and tent area was a very somber place for several months after that fateful July 29, 1942. In the deathly quiet you could almost, but not quite, hear the tell-tale whirring of an A-24 engine trying to get back home to the safety of the 8th Squadron."

Meanwhile, the 13th and 90th Squadrons continued their own missions, staging through Port Moresby to attack enemy airfields and shipping. The 89th Squadron was within a month of getting their first A-20s when something of vastly greater need arrived in Australia--unprecedented leadership.

On August 4 Far East Air Force Commander General George Brett returned to the United States. His replacement, General George Kenney, had arrived six days earlier. On the day Brett left Australia, Kenney flew to Charters Towers to check on his 3rd Bombardment Group.

General Kenney had initially appraised the conditions in the Far East Air Force as "The Goddamest mess you ever saw." At Charters Towers, he found a group of pilots, most of whom were still without planes. He also witnessed the ragged remnants of the 8th Squadron, devastated and demoralized by heavy losses and especially the disastrous July 29 mission. Despite these challenges and tragedies, Big Jim Davies' men were a resourceful and determined lot. In the mess that was the Far East, Air Force Kenney described the 3d Bomb Group as a "Snappy, good looking outfit."

The tragedy so recently heaped upon the 8th Squadron struck a sensitive nerve for General Kenney. This was his alma mater. From October 1919 until the following May Captain George C. Kenney had been Squadron Commander for the 8th. His keen understanding of the Group's history and mission is evident in his memoirs when he wrote of that visit:

"The 3rd, which used to be the 3rd Attack Group back home, did low-altitude strafing and bombing work. They still wanted to be called an Attack Group, so I told them to go ahead and change their name. That organization had trained for years in low-altitude, hedge-hopping attack, sweeping in to their targets under cover of a grass cutting hail of machine-gun fire and dropping their delay-fuzed (sic) bombs with deadly precision. They were proud of their outfit and they liked the name 'Attack' Now the powers that be had changed their name to 'Light Bombardment parenthesis Dive' and they didn't like it. I knew how they felt. I had been an attack man myself, had written textbooks on the subject and taught it for years in the Air Corps Tactical School. It seems like a little thing but it really isn't. Numbers, names, and insignia mean even more to a military organization than they do to Masons, Elks, or a college fraternity."

From that day forward, no matter what name the "brass-hats" at high headquarters chose to give the men of the 3d Bomb Group, they called themselves:

The 3d Attack Group General Kenney's rare insight into the importance of a name went beyond the air group based at Charters Towers. One month later the Far East Air Force became the U.S. Army's Fifth Air Force. For many war-weary, demoralized airmen, that new sense of identity provided a fresh start. They took advantage of it with a vengeance that, in a few short months, ripped aerial superiority from the Japanese.

Kenney's visit to Charters Towers turned into both a reunion and an introduction. It was a return to his roots, the unit he had commanded in his own early days. It also introduced him to the man who would bring to life some of Kenney's own radical and innovative ideas--Captain Pappy Gunn.

The first Douglas A-20 Havoc dive bombers that had been promised to the 3rd Bomb Group had arrived in May. Well-suited to low-level attack, their light armament however was too meager for the demands of the war in the Pacific. Implementation of the new aircraft was delayed while Pappy Gunn and Captain Bob Reugg began experimenting with design changes.

The first Douglas A-20 Havoc dive bombers that had been promised to the 3rd Bomb Group had arrived in May. Well-suited to low-level attack, their light armament however was too meager for the demands of the war in the Pacific. Implementation of the new aircraft was delayed while Pappy Gunn and Captain Bob Reugg began experimenting with design changes.

In August the 89th Squadron began getting its first shipments of new A-20 Havocs. These too required modification. With General Kenney's eager support Pappy began installing four, forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns in the bombardier's compartment (nose) to add massive strafing power. Two 405-gallon fuel tanks were installed in the bomb bay to increase their range, and special racks were invented so the dive-bombers could carry para frag bombs, one of General Kenney's most innovative weapons.

While Pappy was rebuilding dive-bombers, Colonel Davies began sending home the few remaining, battle-weary veterans of the old 27th Bomb Group. Lieutenant Wilkins elected to stay and was transferred to the budding 89th Squadron. Most of the other surviving 8th Squadron pilots and ground crews were relegated to status as support to the other squadrons. Their only combat missions resulted from TDY (temporary duty assignment) to the 89th Squadron. Since July 29 the 8th Squadron had ceased to exist as little more than a resource for the other squadrons.

On September 2 the first six modified A-20s flew to Port Moresby to begin operations. Four days later Lieutenant Wilkins arrived at New Guinea with six more modified Havocs. For the next six months, Wilkins flew repeated missions as a member of the 89th Squadron, many of them missions against Japanese ground troops crossing the Kokoda Trail to within 30 miles of Port Moresby. Additionally, again and again, he returned to bomb and strafe Lae, Salamaua, and other targets north of the high mountains.

When Big Jim Davies turned command of the 3d Attack Group over to Lieutenant Colonel Strickland in October 1942 and returned home, Ray Wilkins was one of the few remaining pilots from the old 27th. Only a few, like Davies, had lived to claim the well-deserved rotation home. Far too many had simply vanished into deep waters or dense jungle, their fate forever unknown.

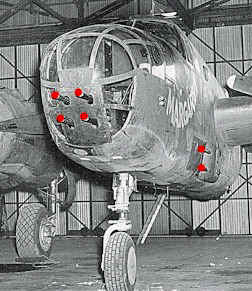

In November Pappy Gunn's remarkable talent for turning A-20s into formidable staffers was turned towards the B-25s that were the staple of the 3d Attack Group's assault on enemy airfields and shipping. First, the bombsights were removed. In a low-level, diving attack from only a few hundred feet, they were unnecessary. In the bombsight's vacant cavity in the nose of the bombers Pappy mounted four, forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns to augment the two 50s on either side of the fuselage.

In November Pappy Gunn's remarkable talent for turning A-20s into formidable staffers was turned towards the B-25s that were the staple of the 3d Attack Group's assault on enemy airfields and shipping. First, the bombsights were removed. In a low-level, diving attack from only a few hundred feet, they were unnecessary. In the bombsight's vacant cavity in the nose of the bombers Pappy mounted four, forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns to augment the two 50s on either side of the fuselage.

The prevailing theory was that with such formidable a fusillade, the bombers could come in fast and low with guns blazing to clear the deck of a ship moments before skipping a 500-pound bomb into its side. When used against enemy airfields, such formidable incoming firepower could drive anti-aircraft gunners for shelter while the B-25s made their low-level pass to drop parafrags. These small, 23-pound parachute-deployed explosives, in turn, would explode on impact or with only a brief delay, shredding enemy fighters and bombers on the ground.

Pappy's skills left 5th Air Force pilots wondering what he would come up with next. One cartoon featured a Pappy Gunn creation that was part bomber, part tank, and part battleship. Indeed, if the modified B-25s hadn't proved so successful on their own, Pappy might have actually built such a contraption. His skill attracted not only General Kenney's attention but that of North American's field representative Jack Fox. (North American was the company that built the B-25 Mitchell.) With the help of Fox, Pappy's proto-type, christened Margaret, began field tests in December.

Pappy's skills left 5th Air Force pilots wondering what he would come up with next. One cartoon featured a Pappy Gunn creation that was part bomber, part tank, and part battleship. Indeed, if the modified B-25s hadn't proved so successful on their own, Pappy might have actually built such a contraption. His skill attracted not only General Kenney's attention but that of North American's field representative Jack Fox. (North American was the company that built the B-25 Mitchell.) With the help of Fox, Pappy's proto-type, christened Margaret, began field tests in December.

Despite the success of these initial tests, and despite Pappy's legendary reputation, the men who would be tasked with flying the modified B-25s remained skeptical. Captain Jack Jock Henebry recalled the sales job Pappy had to do to convince the pilots:

"This airplane is too dangerous," someone said. "With all the guns and ammunition in the nose, you'd have too much weight forward, too far ahead of the designated center of gravity. Where's your center of gravity?"

"Center of gravity?" Pappy answered. "Hell, we took that out to lighten the ship and sent it back to Air Corps Supply."

By the time the first full year of World War II came to a close, the tide was turning in the Pacific. At Guadalcanal U.S. Marines had established a foothold in the Solomons and were turning control over to the U.S. Army while they pulled back to prepare for the next assault. On the north shore of the Papuan Peninsula, American and Australian ground forces were closing on Buna and Gona, poised to turn the strategic north side of the peninsula over to Allied control. At Port Moresby, the A-20s and B-25s of the 3d Attack Group continued their important missions against enemy targets at Lae, Cape Gloucester, Arawe, Gasmata, and against enemy ground forces still hiding in the jungles of New Guinea. Longer range B-17s and B-24s were increasingly attacking further north in deadly night-time, high-altitude bombing missions against Rabaul. Far south in Australia, Pappy Gunn was pushing his crew of mechanics and welders as they worked their magic that would turn B-25 bombers into deadly dive-bombers.

In early January 1943 Buna and Gona fell, and quickly General Kenney began moving his air assets to new fields north of the Owen Stanley Mountains, increasing the range of their reach into enemy territory. In February the 90th Attack Squadron was equipped with the first B-25C staffers rolled out by Gunn and Company at Brisbane. In the opening days of March, a Japanese convoy intent on reinforcing Lae was sighted in the Bismarck Sea, initiating one of the greatest air/sea battles in history.

On March 4 a dozen of Pappy Gunn's modified B-25s of the 90th Squadron saw their first test under squadron commander Major Ed Larner. Jock Henebry was leading the second element when the enemy ships were sighted, and recalled being "scared as hell at the thought of flying right up to their sides at water level."

On March 4 a dozen of Pappy Gunn's modified B-25s of the 90th Squadron saw their first test under squadron commander Major Ed Larner. Jock Henebry was leading the second element when the enemy ships were sighted, and recalled being "scared as hell at the thought of flying right up to their sides at water level."

He remembered:

"Larner peeled off and bore in on the lead cruiser. We watched him go in strafing, get a hit and start after the next one. Well, that instilled tremendous confidence in the rest of us. If he can do it so can we...and all hell broke loose then."

The Mitchells blazed a flaming trail of bullets and bombs across the enemy convoy. Twelve A-20s from the 89th Squadron followed. When the 3d Attack Group had finished its first major combat test of Pappy Gunn's B-25s, left behind were two sinking destroyers (Henebry had mistaken a destroyer for a cruiser), and three sinking transports. Both Grim Reaper squadrons returned to their airfields elated at the success of the first-ever daylight, low-level, skip bombing mission of the war.

The Mitchells blazed a flaming trail of bullets and bombs across the enemy convoy. Twelve A-20s from the 89th Squadron followed. When the 3d Attack Group had finished its first major combat test of Pappy Gunn's B-25s, left behind were two sinking destroyers (Henebry had mistaken a destroyer for a cruiser), and three sinking transports. Both Grim Reaper squadrons returned to their airfields elated at the success of the first-ever daylight, low-level, skip bombing mission of the war.

(On April 30 Major Ed Larner was killed in an air crash. Captain Jock Henebry assumed command of the 90th Squadron.)

After the great success of the March 4 air/sea battle, the only disappointed member of the 89th Squadron was Lieutenant Raymond Wilkins. On leave to Australia during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, he had missed out on all the action. Two of his old friends from the 8th Squadron, on temporary assignment to the 89th, did see action and were awarded Distinguished Flying Crosses.

If there was any consolation for Wilkie it was to be found in fond memories of that brief R&R in Australia. A beautiful young Australian girl named Phyllis had attracted his attention. Upon his return to New Guinea, he had his crew chief Melvin Freeman paint her nickname on the nose of his A-20. When Captain Wilkins transferred back to the 8th Squadron as Operations Officer in May and began flying B-25s, it too was named Fifi.

If there was any consolation for Wilkie it was to be found in fond memories of that brief R&R in Australia. A beautiful young Australian girl named Phyllis had attracted his attention. Upon his return to New Guinea, he had his crew chief Melvin Freeman paint her nickname on the nose of his A-20. When Captain Wilkins transferred back to the 8th Squadron as Operations Officer in May and began flying B-25s, it too was named Fifi.

That same month John Hill, Finlay MacGillivary, Bob Anderson, Ed Chudoba, and Captain Ostreicher rotated back to the United States. These five, aside from Ray Wilkins, were the last remaining 8th Squadron pilots from the dark days of the A-24 Dauntless. Captain Wilkins could have joined them in the return home, having already served fourteen months in combat, but he declined rotation to remain with his men.

Rabaul - Japan's Pearl Harbor

The spring and summer of 1943 was a busy time for the 3d Attack Group, all four squadrons of which were now based in New Guinea. The 8th, 13th and 90th Squadrons were equipped with modified B-25s and the 90th Squadron with A-20 Havocs. In desperation, the Japanese struggled to reinforce their far-flung empire in the Southwest Pacific. A steady flow of troops, supplies, and aircraft was ferried regularly from Tokyo to Rabaul at the north tip of New Britain Island. From there they were dispersed east to Bougainville and the Solomons, south to Cape Gloucester and besieged Lae, and west to the north coast of New Guinea at Wewak.

Rabaul's supply chain to the Solomons gained new precedence for Japanese war planners on June 30. Admiral Halsey landed the 43d Infantry Division on New Georgia Island northwest of Guadalcanal, and American soldiers were knocking on Bougainville's back door. From the Munda Airstrip on New Georgia, American aircraft-mounted regular missions against Bougainville, and Rabaul as well.

Meanwhile, B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators based in Australia and New Guinea continued to pound Rabaul from miles above its sheltered Simpson Harbor. The 3d Attack Group Mitchells and Havocs simultaneously did their best to intercept ships at sea. Hunting became slim-Pickin's but remained quite dangerous. Since the horrible defeat in the Bismarck Sea, seldom did ships travel any longer in convoys, and never without impressive fighter cover.

On July 9 Wilkie's good friend Bill Webster was shot down by seven enemy fighters 50 miles south of Salamaua. It was a solemn reminder to Wilkins, who had lost all of his close friends in the deadly July mission one year earlier, that there was grave danger in getting too close to the men you flew with. It was a lesson especially driven home to him by his leadership roles. Fortunately, on this rare occasion, Webster and most of his crew were rescued by an Australian coast-watcher and returned to the squadron.

Promoted to captain in February, upon his return to the 8th Squadron Ray Wilkins led repeated barge hunts and low-level strikes against Salamaua, Lae, and other enemy strongholds. On July 20 he led the attack on the Gogol River bridge near Madang, the deepest penetration by American attack bombers to that date.

Promoted to captain in February, upon his return to the 8th Squadron Ray Wilkins led repeated barge hunts and low-level strikes against Salamaua, Lae, and other enemy strongholds. On July 20 he led the attack on the Gogol River bridge near Madang, the deepest penetration by American attack bombers to that date.

On July 28 he led the squadron in an attack against two destroyers off Cape Gloucester. Without fighter cover and under an intense barrage of surface-to-air fire, he made two passes on one of the enemy ships. Returning through a melee of enemy Zeroes, his B-25 was riddled with bullets but somehow, he managed to break free and nurse it home. The very next day he returned to find one surviving destroyer, scoring two direct hits and sending it to the ocean floor. For that action, he was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross. Soon thereafter he received an Oak Leaf Cluster to wear on his DFC, this for completing 50 combat missions.

In mid-August General Kenney unleashed his heavy bombers and attack squadrons against the heavily reinforced Japanese airfields around Wewak. After a year of support roles to the 89th Squadron, and a summer of routine barge hunts and small strafing missions, this marked the first major operation for the 8th Squadron since the loss of six of seven A-24s the summer before.

All three B-25 squadrons of the Grim Reapers were all involved in the important August 17 mission led by Group Commander Colonel Donald Hall. Twelve 8th Squadron Mitchells under Captain Wilkins attacked the Boram airdrome, destroying 25 enemy fighters and bombers on the ground and destroying at least twenty more with strafing rounds and parafrags. The 13th and 90th Squadrons had similar successes. The 3d Attack Group suffered no losses.

The following day 8th Squadron Commander Major James Downs led a second attack against Boram. Again, the mission met with great success and combined with the efforts of other groups, in two days the men of the 5th Air Force destroyed as many as 200 enemy planes, most of them on the ground. Over Wewak the 38th Bomb Group lost Major Ralph Cheli, who was subsequently awarded the Medal of Honor. Over Boram, the 8th Squadron of the Grim Reapers lost two B-25s. William Webster recalls:

"This loss was the only drawback to an otherwise pair of successful missions that really marked the rebirth of the 8th Squadron, literally from the ashes of July 29, 1942. At last, we had earned respectability and self-confidence in combat after a year of virtual anonymity. Floyd Rogers et al were finally avenged."

On August 25 Major Raymond Wilkins leads his squadron in the first low-level attack on Hansa Bay. Diving into a withering hail of ground fire Wilkins hit two enemy ships, sinking one while the rest of his squadron claimed five more. Three days later he led three squadrons of Grim Reapers back to Hansa Bay where he personally scored direct hits on two more ships. For that action, he was awarded a second Oak Leaf Cluster for his Distinguished Flying Cross.

Early in September Major Downs was promoted and moved to Group Headquarters, preparatory to assuming Group command upon the departure home of Colonel Hall. Major Raymond Wilkins, the last survivor of the original 8th, became squadron commander. Always a leader, Bill Webster remembers the impact of Wilkie's new role as a commander had on him. "He (Wilkins) had a unique business-like personality, especially when compared to the happy-go-lucky styles of Ed Larner and Jock Henebry. He (had) turned down two earlier chances to end his combat tour because he felt he could personally influence the outcome of the war by his own commitment and example. Now he had his own squadron, and he'd shown everyone how to run a combat unit.

"He moved away from the other pilots, because, as he told me, 'You can't be both a good friend and a good combat squadron commander at the same time and I am choosing the latter.

"He seldom laughed or joked with the pilots at meetings. He addressed everyone by his rank, and he ran a tight ship both in Squadron Headquarters and on the flight line. He seemed to know what was going on all the time in every section."

For Major Wilkins, command and leadership were inseparable characteristics. Over the next eight weeks, virtually every mission tasked to the 8th Squadron was led by its squadron commander. These included the first mission against enemy shipping near Kairuru Island (Wewak) on September 27. Leading all three Mitchell squadrons in the mission that wreaked devastation on the enemy supply line, Wilkins personally destroyed a 4,000-ton ship in Victoria Bay. For that, and for his leadership in the highly-successful raid, he was awarded a third Oak Leaf Cluster to be worn on his Distinguished Flying Cross.

Lae, the last Japanese bastion on the Papuan Peninsula, fell to Australian ground troops supported by the Fifth Air Force on September 16. By October the enemy forces on New Guinea's north coast at Wewak, at Cape Gloucester across the Huon Gulf, and across the southern coast of New Britain were reeling from the unrelenting air attacks. Further east in the Solomons, New Georgia was in Allied hands and the captured Munda Air Field had been rebuilt to support the next step in the leap-frog advance, the long-anticipated assault on Bougainville.

Tokyo scrambled to reinforce the region, pulling task forces from other critical duty stations and sending them to New Guinea and Bougainville. Hundreds of fighters and bombers were marshaled for deployment in the region and thousands of infantrymen, tanks, and equipment were shipped south. As always, all enemy assets marked for duty in the region had to pass through Rabaul.

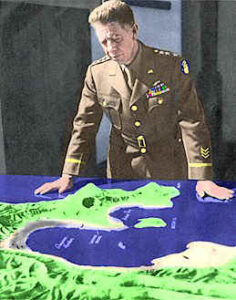

Gibraltar of the Pacific

General George C. Kenney stared intently downward, as he had one so many times in the previous year, at his large table-top mockup of Simpson Harbor and the nearby fortress that was Rabaul. From the earliest days of the war in the Southwest Pacific the critical Japanese port had been the major obstacle in Allied advances throughout the region. Kenney's boss, General Douglas MacArthur, believed Rabaul to be the key to the Philippines. It was the wall, the barrier, that had to be destroyed before his promised return.

General George C. Kenney stared intently downward, as he had one so many times in the previous year, at his large table-top mockup of Simpson Harbor and the nearby fortress that was Rabaul. From the earliest days of the war in the Southwest Pacific the critical Japanese port had been the major obstacle in Allied advances throughout the region. Kenney's boss, General Douglas MacArthur, believed Rabaul to be the key to the Philippines. It was the wall, the barrier, that had to be destroyed before his promised return.

Heavy bomber missions had targeted Rabaul again and again since the summer of 1942. The surrounding jungles and waters were strewn with the rusting hulks of American B-24s and B-17s, and the bodies of valiant airmen.

One of the earliest such missions had been mounted on August 6-7, 1942, the day U.S. Marines launched the first ground offensive of World War II at Guadalcanal. To keep enemy aircraft based out of Rabaul from attacking the Marines, a B-17 strike against the harbor had been ordered. One of the B-17s never returned. Somewhere over New Britain, after dropping its bombs, it fell to a hail of enemy gunfire from attacking Zeros. The pilot, Captain Harl Pease who had survived the fall of the Philippines, was never heard from again. Posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for that mission, he was the second Army airman (after Jimmy Doolittle) to earn the Medal.

Long-range, high-altitude bombing missions had continued against Rabaul through the last months of 1942 and into the next year. On January 5, 1943, Brigadier General Kenneth Walker was lost in a daylight bombing raid over Rabaul. He became the third Army Air Force Medal of Honor recipient of the war. His tragic loss was felt throughout the Fifth Air Force. Ultimately the highest-ranking MIA (missing in action) of World War II, Walker had been commander of Kenney's V Bomber Command.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1943 Japanese troops, aircraft, and supplies continued to flow through Rabaul. Fifth Air Force heavy bombers mounted regular missions despite heavy losses. By fall, with advanced airfields and Pappy Gunn fuel tank modifications, Kenney's fighters and light bombers were at last in the range of Simpson Harbor. In October, with Admiral Halsey's forces in the east preparing to make their next move up the Solomon Chain to attack Bougainville on November 1, Kenney mounted his largest campaign to date to knock out, or at least neutralize, Rabaul. It was a formidable assignment. Rabaul was known throughout the theater as The Gibraltar of the Pacific.

Simpson Harbor is the world's most protected seaport, a natural inlet surrounded on three sides and lying in the shadow of four semi-active volcanoes. The city of Rabaul, heavily fortified by Japanese troops in 1943, lies at the west end of the harbor. In addition to more than 100,000 ground troops to garrison the Gazelle Peninsula and man more than 350 anti-aircraft guns, five major airfields stood guard ominously at all approaches. In October General Kenney ordered his fighter and attack squadrons to begin assaults on these airfields on every day in which the weather was suitable for flying.

Simpson Harbor is the world's most protected seaport, a natural inlet surrounded on three sides and lying in the shadow of four semi-active volcanoes. The city of Rabaul, heavily fortified by Japanese troops in 1943, lies at the west end of the harbor. In addition to more than 100,000 ground troops to garrison the Gazelle Peninsula and man more than 350 anti-aircraft guns, five major airfields stood guard ominously at all approaches. In October General Kenney ordered his fighter and attack squadrons to begin assaults on these airfields on every day in which the weather was suitable for flying.

The attack squadrons that had so effectively shellacked the Japanese airfields on the northern New Guinea coast in August now called the technique of low-level strafing and para frag bombing "Wewaking." On October 12, in one of the largest raids yet mounted on the Gazelle Peninsula, the 3d Attack Group Wewaked the major airfield at Rapopo.

Major John Jock Henebry (right) led the 90th Squadron over Rapopo in his B-25 Notre Dame De Victorie. Even at low altitudes, Rabaul was clearly visible in the distance. Its sheltering Simpson Harbor was filled with enemy ships. They were "juicy, off-limits targets," he recalled. "Top priority for us then remained the destruction of the enemy air capability."

Major John Jock Henebry (right) led the 90th Squadron over Rapopo in his B-25 Notre Dame De Victorie. Even at low altitudes, Rabaul was clearly visible in the distance. Its sheltering Simpson Harbor was filled with enemy ships. They were "juicy, off-limits targets," he recalled. "Top priority for us then remained the destruction of the enemy air capability."

Joining Jock and his crew of four in Notre Dame De Victorie was an extra passenger. INS correspondent Lee Van Atta had hitched a ride for this mission and then described it vividly in the story he filed.

Eye Witness Story of Rabaul Smash

By Lee Van Atta

International News Service (October 12, 1943)

ABOARD AN AMERICAN MITCHELL BOMBER EN ROUTE FROM RABAUL

Rabaul, a key Jap bombardment base in the Southwest Pacific, was devastated today by a mighty Allied air assault, rivaling the enemy's Pearl Harbor raid. The smoking, flaming ruins of the bombardment base seared an unforgettable, crimson impression into our minds as we hurtled our way off target.

Caught apparently with only the briefest warning, the Rapopo Airdrome--nesting ground for Nippon's Western Pacific heavy aircraft strength--learned in all its devastating intensity the power of an American warplane attack.

Even as our forward guns began cutting a swath across Rapopo, other strafing Mitchell bombers could be seen racing against Vunakanau Airdrome. Seconds later the scene was etched with billowing clouds of black smoke and towers of fire.

To coin a word, Rabaul was "Wewakized." The impossible has been done again--and with the accomplishment of the impossible, months of planning and preparations and hours of tense anticipation have come to an end.

It was the first time in the history of the Pacific warfare that escorted assault and bombardment units had been sent to penetrate the Japs' fortress-like ack-ack defenses around Rabaul.

*Excerpts from the full story

All three Grim Reaper B-25 squadrons attacked Rapopo. Leading the 8th Squadron was Major Raymond Wilkins. It was his 86th combat mission in twenty-two months of combat duty, unequaled by any man in the Fifth Air Force. A fifth award of the Distinguished Flying Cross, proffered for his heroic leadership on October 12, was in acquiescence to Major Wilkins' preference awarded instead to his second-in-command.

Additional missions against enemy airfields around Rabaul continued for two weeks. They were the first combat assignments in months that the 8th flew without Wilkins. Three days after the Rapopo raid, Major Wilkins afforded himself a well-deserved R&R in Australia to spend time with Phyllis.

A few days later Wilkins cut short his respite to return to his squadron early. He had learned that the single largest, and most important mission against Rabaul was scheduled for the closing days of the month. Major Wilkins would not commit his airmen to so dangerous and critical a foray without his personal leadership.

On Sunday, October 31, virtually every plane of the Fifth Air Force was fueled and standing by for the green light that would launch the mission to Wewak Rabaul and Simpson Harbor. After three hours, a P-38 near the target reported that the weather was too marginal for the mission. The squadrons shut down their engines and returned to their tents intense anticipation of another attempt the following day. Bill Webster remembers that afternoon vividly:

"Two things happened to me that undoubtedly changed my life. First, I was notified by Group Personnel that I was eligible fore rotation back to the States and that I was being reassigned to Group Operations for a week or so while waiting air transport to Brisbane. I was speechless--snatched right out of the fire just in the nick of time. I was going home to see my wife and meet my six-month-old son!!! I started packing immediately.

"That night I got word to report to Wilkins' tent. He told me he was happy for my good news and that he had three bits of good news also.

"First, the 8th Squadron was new to receive new A-20s shortly. Next, he was scheduled to move up to Group Headquarters. Third, he and his fiancée had set a wedding date late in December.

"After mutual congratulations, he put a question to me that I'll never forget--'Will you delay your departure long enough to fly one more mission for the 8th Squadron. I need you as a flight leader and deputy commander on this upcoming Rabaul mission.'

"My immediate thought was an emphatic negative, but I remembered his twenty-two-month stint of combat flying, particularly the first six months in the A-24s and all of the times he had put his personal war effort above possible personal preferences. Against my better judgment, I said I would honor his request to fly this last mission."

On November 1 reconnaissance planes again reported unsatisfactory weather all the way from New Guinea to the north side of New Britain Island. One recon pilot over Rabaul did, however, manage to break through the clouds long enough to take photographs. When reviewed back at headquarters they depicted a stunning buildup in the Japanese port. When the mission to Simpson Harbor finally launched on November 2, Major Raymond Wilkins, Bill Webster, and the other men of The Devil's Own Grim Reapers knew they would be flying into hell itself.

Bloody Tuesday, November 2, 1943

Major John Jock Henebry sat impatiently in the cockpit of his B-25 Notre Dame De Victorie. The commander of the 90th Attack Squadron was a seasoned veteran. With 79 missions behind him, he was second in longevity only to Major Raymond Wilkins.

Major John Jock Henebry sat impatiently in the cockpit of his B-25 Notre Dame De Victorie. The commander of the 90th Attack Squadron was a seasoned veteran. With 79 missions behind him, he was second in longevity only to Major Raymond Wilkins.

This was the third straight day in a routine that had twice ended in a mixture of emotions: both disappointment and relief. The pilots of the 3rd Bomb Group had risen each morning at 4 a.m. for a breakfast of canned grapefruit juice, French toast (made with dehydrated eggs and powdered milk,) some peanut butter and cheese, and coffee. By 6:30 a.m. both pilots and crew were in their aircraft to begin the long wait for the signal to start engines and takeoff to hit Rabaul. As the hours dragged on the interior of the planes warmed with the rising sun, making them insufferably hot. Men, nervous about the mission they both feared and anticipated, became impatient to launch if for no other reason than to find cooler air.

Jock had been involved in virtually every major mission of the previous year: The Battle of the Bismarck Sea, Wewak, Lae, and the previous two weeks of assault on the airfields near Rabaul. He knew, however, that if the weather improved, this would be his most important mission to date, perhaps of the entire war. If the weather didn't improve the American ground forces that had landed the previous day at Empress Augusta Bay at Bougainville would be at the mercy of an armada of enemy aircraft based out of Rabaul.

The mission itself was to be an all P-38/B-25 effort, 84 strafer/bombers from three bombardment groups including the 3rd Attack Group, covered by an equal number of P-38 fighters. Prepared to launch from a dozen airfields on the north coast of the Papuan Peninsula, the aerial armada was to assemble over the Solomon Sea and proceed northward, skirting New Britain to slip into Rabaul from the east via St. George's channel. The tactical plan called for two fighter squadrons to sweep Simpson Harbor three minutes ahead of the second wave to neutralize enemy ground defenses.

The mission itself was to be an all P-38/B-25 effort, 84 strafer/bombers from three bombardment groups including the 3rd Attack Group, covered by an equal number of P-38 fighters. Prepared to launch from a dozen airfields on the north coast of the Papuan Peninsula, the aerial armada was to assemble over the Solomon Sea and proceed northward, skirting New Britain to slip into Rabaul from the east via St. George's channel. The tactical plan called for two fighter squadrons to sweep Simpson Harbor three minutes ahead of the second wave to neutralize enemy ground defenses.

That first sweep was to be followed by four squadrons of B-25s from the 345th Bombardment Group under Major Ben Fridge. Escorted by two more P-38 fighter squadrons, this second was to split up and drop white phosphorus bombs and strafe either side of the harbor, masking the incoming third wave's attack on the Japanese ships.

Major Jock Henebry had been tasked with leading that third wave's assault, followed by four more waves of B-25s undercover Captain Danny Roberts' 433d Fighter Squadron. If the mission went as planned, the massive raid on Simpson Harbor could severely cripple the enemy supply chain with little Allied loss. Colonel Freddy Smith of First Air Task Force estimated that the two-week campaign on the airfields around Rabaul had reduced the enemy fighter strength to as few as fifty aircraft.

What Colonel Smith did not know was that in the previous two days, during which time the mission had been delayed by poor weather, more than 150 additional Japanese fighters had been rushed into the area to cover a harbor full of ships. When at last on Tuesday, November 2, Jock Henebry got the green light to start engines and take off, he and his trailing four squadrons were flying into a hornet's nest.

Major Henebry was first to lift off, followed by Major Richard Ellis in Seabiscuit who would fly on Jock's wing. Joining Ellis in his B-25 was INS correspondent Lee Van Atta, who had flown combat missions with the 3rd Attack Group repeatedly in order to send reports of their work back home.

Following the 90th Squadron into battle was the 13th under the command of Captain Walter J. Hearn. Captain Art Small, originally tasked to lead the 13th Squadron, unexpectedly fell ill in the early morning hours before the mission unfolded. Captain Hearn was his replacement. Unfortunately, Hearn had not been involved in the briefings for the mission and accepted this backup role at a disadvantage.

Third, in rotation and leading, two squadrons from the 38th Bomb Group was Major Ray Wilkins in Fifi. Captain Bill Webster, voluntarily flying this last mission before returning home to meet his six-month-old son, was preparing to lead his own 3-plane element in the 8th Squadron formation. Both men realized that by the time they entered the harbor any hoped-for advantage of surprise would be gone. Theirs was a most unenviable position. Bill Webster recalls well that last mission:

"This was to be a maximum effort mission, and eleven serviceable aircraft were all we (8th Squadron) had left after the losses of August, September, and October. We planned to have ten planes on our strike with the 11th plane as a spare in case we had any ground aborts.

"As planned, the 8th Squadron was last to take off, and this made for another 10-12 minute delay, waiting for the other two squadrons to go. As I recall, our first eight planes took off okay, but the ninth and tenth, Bridges and Virdon, aborted because of excessive rpm drop on magneto checks. The eleventh plane (Vinson in the spare) took off to round out the three 3-plane flights. It was not an auspicious beginning, but for better or worse, we were finally on our way to Simpson Harbor.

"About 20 minutes after takeoff, Vinson apparently developed fuel transfer problems and pulled out of the formation to return to base. I am sure Wilkins was furious, but he would not break radio silence to reprimand. The other eight continued on, last in the long string of nine squadrons of B-25s heading northeast at about 3,000 feet."

"The escorting P-38s took off as planned about 30 minutes after the B-25s and soon caught up with us as we neared the IP. Wilkins used the customary visual signal, a slow fish-tailing of his aircraft, to spread out the squadron's planes to test all guns and then we formed back up in two "V"s and one two ship section behind and slightly to the east of the 13th Squadron which in turn was following the 90th."

After more than two hours of low-level flight over the waters east of New Britain Island the formation had covered most of the 450-mile distance from their airfields to St. George's Channel. By the time the narrow slot that separated New Britain from the southern tip of New Ireland came into view, the droppable turret tanks necessary for the long flight were empty and were jettisoned.

The American pilots had hoped that their attack would surprise the enemy but labored on under no delusion that their low-level approach had hidden them from Japanese radar. All hope for surprise vanished over the St. George's Channel when the lead elements sighted two Japanese destroyers passing through the narrow strip at a high speed. Jock Henebry recalls: "The temptation to make a pass at these two meaty targets was overcome in favor of keeping our flying pattern until we reached our primary targets, the ships of Simpson Harbor.