The Sullivan Brothers

Written by C. Douglas Sterner

Des Moines "Register", January 4, 1942

Five husky Waterloo brothers who lost a "pal" at Pearl Harbor were accepted as Navy recruits yesterday at Des Moines. All passed their physical exams "with flying colors" and left by train last night for the Great Lakes (Ill.) naval training station. "You see," explained George Sullivan, "a buddy of ours was killed in the Pearl Harbor attack, Bill Ball of Fredericksburg, Iowa." "That's where we want to go now, to Pearl Harbor," put in Francis, and the others nodded.

Five husky Waterloo brothers who lost a "pal" at Pearl Harbor were accepted as Navy recruits yesterday at Des Moines. All passed their physical exams "with flying colors" and left by train last night for the Great Lakes (Ill.) naval training station. "You see," explained George Sullivan, "a buddy of ours was killed in the Pearl Harbor attack, Bill Ball of Fredericksburg, Iowa." "That's where we want to go now, to Pearl Harbor," put in Francis, and the others nodded.

"Which one?" Thomas Sullivan asked. It was early on the morning of January 11, 1943, and Tom was the only one moving about the kitchen of the house at 98 Adams Street in Waterloo, Iowa. He had awakened that morning to prepare for work and, while fixing breakfast, noticed the black sedan arrive. The three men in Naval uniforms had been welcomed inside. The Sullivan patriarch knew before they spoke that they were bringing news of his sons. He also knew the news wouldn't be happy news.

Lieutenant Commander Truman Jones swallowed hard. It was the saddest, most disagreeable task of his Navy career. "I'm sorry. All five," he said matter of factly. There was no other way to break this kind of news.

As the rest of the family gathered in the living room, mother Alleta, sister Genevieve, and Katherine Mary, wife of the youngest of the five Sullivan brothers; it was a moment filled with sorrow and grief. Commander Jones steeled himself to finish his unenviable task.

"The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your sons Albert, Francis, George, Joseph and Madison Sullivan are missing in action in the South Pacific."

The news wasn't completely unexpected. Over the last month, there had been hints of something amiss. The lack of mail from boys accustomed to writing home regularly, the neighbor a week earlier who had received a letter from her own sailor son stating "Isn't it too bad about the Sullivan boys? I heard that their ship was sunk", and perhaps even the sense of a mother's intuition had left the family with the reason for concern.

Within the hour, the Naval officers were gone. Thomas Sullivan began to deal with the impact of the statement that morning while going about his tasks aboard a trainload of war supplies headed east. It had been a difficult decision, leaving for work, but Tom Sullivan had seldom missed a single day of the important freight runs. If Tom's trains didn't run on time, important war supplies might be delayed, and other American boys might die. "Shall I go?" he had asked his wife that morning.

"It's all right, Tom," Alleta had replied. "It's the right thing to do. The boys would want you to, there isn't anything you can do at home."

The big house at 98 Adams Street seemed suddenly very empty. Only the women and 22-month old Jimmy Sullivan, son of the youngest Sullivan brother Albert, remained. The Sullivan women pulled together as the family always had. "Commander Jones only said 'missing in action'," Alleta struggled through her own doubts to reassure her daughters. It was a shallow hope, but it was hopefully just the same. If only one survived then perhaps there would be hope for a second, a third, who knew for sure. One thing was certain, if hope existed for even one, hope existed for all. The Sullivan Brothers had been close, looking out for each other, enlisting together and living by the family motto they had echoed to a Naval recruiter only a year earlier: "We Stick Together"

Friday, November 13, 1942

Off the shores of Guadalcanal

The yellow-black smoke of battle had cleared from the skies as the sunset in the South Pacific on that fateful day in November. The deep swells of the ocean, however, still bore the scars of the previous night's battle and the early morning of death and disaster. A thick, black layer of oil moved with the currents, and in the midst of the oil floated the debris of an American light cruiser, the last remnants of the USS Juneau. Desperate sailors clung to the debris, most of them wounded, all of them frightened. They were all that remained of USS Juneau's crew of 698 American boys. It was impossible to count the survivors, probably somewhere between 90 and 140, but such a count would have been worthless anyway. Wounds, injuries, and the unforgiving sea diminished their numbers with each passing hour.

The heat of the tropical sun gave way to a bone-chilling night, pierced by the moans and cries of men suffering unimaginable horrors. The cries and moans added an eerie atmosphere to a scene already beyond human comprehension. The sounds would haunt the dreams of survivors for the rest of their lives, assuming that any of the men should survive. And then, across the waters, could be heard another desperate voice crying hopelessly into the darkness: "Frank?" "Red?" "Matt?" "Al?" It was the voice of George Sullivan, the oldest of five brothers who served on the Juneau. George had survived and now sought desperately for his younger brothers.

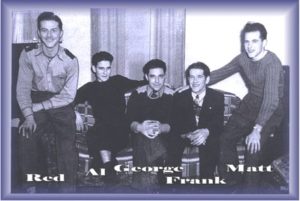

Born and raised in Waterloo, Iowa; the five Sullivan brothers had always stuck together. From George, the oldest, to Al, the youngest; there was only a 7 year age difference. They had lived together at the plain, large house at 98 Adams Street, along with one sister Genevieve, and their parents Thomas and Alleta, and grandma Mae Abel. The longest period of time the boys had ever been separated had been the four years prior to World War II when George and Francis Henry, second oldest of the quintet and usually called "Frank", had served in the Navy. Even then, the two brothers had served most of their hitch together, on the same ships.

George Sullivan was discharged after fulfilling his four-year commitment on May 16, 1941. Eleven days later, Frank received his own discharge and both boys returned to the family home. Six months later they listened intently to reports of the attack at Pearl Harbor. Former shipmates and friends still on active duty and serving in the Hawaiian port, not to mention two brothers from nearby Fredericksburg, were under fire and both Sullivan boys felt both a sense of helplessness and anger. They determined that night to return to service. This time Joseph Eugene whom they all called "Red", Madison Abel "Matt", and even Albert Leo "Al", insisted on joining them. Their resolve was further strengthened when, just prior to Christmas, they learned the fate of the Fredericksburg brothers, Bill and Masten Ball. Masten had survived the day of infamy, but Bill, who had frequented the Sullivan house and perhaps even "been sweet" on sister Genevieve, had gone to a watery grave aboard the U.S.S. Arizona.

The five brothers who had always done everything together walked into the local Navy recruiting station together. Though Al, just nineteen years old and married less than two years would have qualified for a deferment from combat service, he insisted on being with his brothers. He would leave behind not only a young wife but little Jimmy Sullivan, his ten-month-old son. The Navy was desperate for men in the early days after the destruction at Pearl Harbor and quickly welcomed the Sullivan brothers until the determined young men threw a new "wrinkle" into their enlistment plans. George had echoed the sentiment the night of December 7th when the five young men had made their decision. "Well, I guess our minds are made up...when we go in, we want to go in together. If the worst comes to worst, why we'll all have gone down together."

As they stood in the recruiting office, they demanded that the Navy assure them that they would be allowed to serve together on the same ship. When they couldn't get the guarantee that day, they took their demands all the way to Washington, D.C. In a letter to the Navy Department they explained their desire to defend their country but insisted that if the Navy wanted the Sullivan brothers, it would have to be a package deal. "We stick together!" Finally, the Navy agreed. The transcripts of all five Sullivan brothers reveal that each was "Enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve on 3 January 1942" and together they were "Transferred to the Naval Training Station, Great Lakes, Illinois." Exactly one month later, the individual orders for each of the five sailors read, "Transferred to the receiving ship, New York, for duty in the USS Juneau detail and onboard when commissioned."

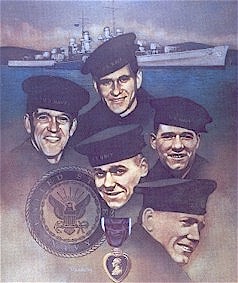

Eleven days later, on February 14, 1942, the USS Juneau was commissioned. The five Sullivan brothers became instant celebrities when photographers captured the photo seen in the background of this page, a photograph that symbolized not only the sense of brotherhood among those who volunteered to defend our Nation but the commitment of an entire family from the heartland of America. George, Frank, Red, Matt, and Al enjoyed the spotlight that day. They also shared the spotlight with four other brothers, Joseph, James, Louis, and Patrick Rogers. In time, a total of 9 sets of brothers would serve on the USS Juneau. But no family in America could match the record of the five Sullivans.

Eleven days later, on February 14, 1942, the USS Juneau was commissioned. The five Sullivan brothers became instant celebrities when photographers captured the photo seen in the background of this page, a photograph that symbolized not only the sense of brotherhood among those who volunteered to defend our Nation but the commitment of an entire family from the heartland of America. George, Frank, Red, Matt, and Al enjoyed the spotlight that day. They also shared the spotlight with four other brothers, Joseph, James, Louis, and Patrick Rogers. In time, a total of 9 sets of brothers would serve on the USS Juneau. But no family in America could match the record of the five Sullivans.

Late in May, George, Matt, and Al came home one last time. It gave Al the opportunity to say farewell to his young wife, Katherine Mary. For her, it must have been a time of mixed emotions. She had lost her mother at the age of seven. Now she was losing her husband, if even for a brief few years, possibly forever.

In order to survive on Al's small Naval salary, she had moved in with Tom and Alleta. She could have kept her husband out of harm's way, used his role as husband and father to defer him from combat. But she knew the Sullivan brothers well, loved Al enough, not to come between the brothers. "Don't worry," perhaps he reminded her, "We stick together!"

In order to survive on Al's small Naval salary, she had moved in with Tom and Alleta. She could have kept her husband out of harm's way, used his role as husband and father to defer him from combat. But she knew the Sullivan brothers well, loved Al enough, not to come between the brothers. "Don't worry," perhaps he reminded her, "We stick together!"

A sixth Sullivan joined the Navy that day, though he was only 15-months old. Little Jimmy donned his uniform cap to pose with his father and uncle Matt for local media. Then it was time for a final farewell. On June 1st the USS Juneau sailed out of New York and into history, carrying nearly 700 sailors including Joseph, James, Louis, and Patrick Rogers (James & Joseph Later transferred to another ship), William and Harold Weeks, Russell and Charles Combs, Albert and Michael Krall, George and John Wallace, Curtis and Donald Damon, Richard and Russell White, Harold and Charles Caulk & The Five Sullivan Brothers.

Thursday, November 12, 1942

The war in the Pacific was not going well. Despite the "moral victory" of Jimmy Doolittle's bombing raid on Tokyo in April and the victory at Midway in June, the Japanese seemed almost invincible. The Philippine Islands had fallen, and the one thread of hope rested with the battle-weary Marines who clung tenuously to a small Pacific Island called Guadalcanal. Though the Marines controlled most of the island, the Japanese still ruled the surrounding seas and rained nightly death from their heavy guns on warriors who had suffered too much for too long. On this night a Japanese fleet of twenty ships formed in two columns began a run through the narrow passage called "the slot", from which they could bombard the Marines on Guadalcanal.

Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan sailed out to meet them on his flagship cruiser U.S.S. San Francisco. He's outnumbered, the outgunned force consisted of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers. Shortly before 2 A.M. on Friday the 13th the two forces met. Rear Admiral Callaghan did the unthinkable, forging his way up the middle of the two enemy columns, his ships firing in both directions. The half-hour battle was unlike any in Naval history, close quarters with friend and foe nearly ramming each other in the darkness, the skies exploding in brilliant flashes that could be seen by war-weary Marines in their muddy fox holes on Guadalcanal. Then, as silence fell once again upon the South Pacific, the Americans assessed the damage. The U.S.S. San Francisco was badly damaged, Admiral Callaghan killed in action. Below deck Captain Cassin Young, one of only five living Medal of Honor recipients from the Pearl Harbor attack was also wounded and later died. Four of the eight destroyers had fallen to the enemy guns, a fifth left limping towards safety. Of the five cruisers, four were badly damaged, among them the USS Juneau.

As daylight dawned, the Juneau joined the floundering San Francisco, the cruiser Helena and destroyers Sterett, Fletcher, and O'Bannon. Save for the floundering Portland and the destroyer Aaron Ward which was being towed to the refuge, they were the only survivors of the battle.

Aboard the Juneau the wounded were being tended, George Sullivan among them. Below deck, a torpedo hit had killed as many as twenty sailors and badly crippled the cruiser. Daylight revealed the Juneau sitting about 4 feet lower in the water and Captain Swenson was concerned that the keel might have broken. Three pharmacists mates were exchanged to the more badly damaged San Francisco to tend the wounded. George Sullivan, his injury treated, returned to duty near the depth charge racks. Below deck, his brothers went about their jobs, Al and Matt in the loading room and Frank and Red in damage control parties. Death, fear, and the smell of leaking fuel filled the broken body of the Juneau.

Anxious eyes watched the skies for enemy planes. The real threat lay below the surface, where Commander Minoru Yokota of the Japanese submarine I-26 scanned the San Francisco through his periscope. The heavy cruiser was a prime target, an easy kill. At 11 A.M. on that Friday morning, he issued the command to launch two torpedoes. Alert lookouts aboard the San Francisco noticed the wake of the underwater warheads and the San Francisco began a turn. Both barely missed the cruiser and continued on. The first ran out of steam, broke water, and then sank to the bottom of the ocean. The second continued its course on a direct line with the Juneau. Less than a minute later, it struck the Sullivan Brother's ship and exploded. The Juneau didn't sink, it vaporized!

Anxious eyes watched the skies for enemy planes. The real threat lay below the surface, where Commander Minoru Yokota of the Japanese submarine I-26 scanned the San Francisco through his periscope. The heavy cruiser was a prime target, an easy kill. At 11 A.M. on that Friday morning, he issued the command to launch two torpedoes. Alert lookouts aboard the San Francisco noticed the wake of the underwater warheads and the San Francisco began a turn. Both barely missed the cruiser and continued on. The first ran out of steam, broke water, and then sank to the bottom of the ocean. The second continued its course on a direct line with the Juneau. Less than a minute later, it struck the Sullivan Brother's ship and exploded. The Juneau didn't sink, it vaporized!

George Sullivan slowly began to realize where he was, what had happened. The Juneau no longer rode the swells of the South Pacific, only debris was left of that once-proud Naval cruiser. The explosion was so intense that it ripped apart the Juneau, and witnesses to the disaster aboard the San Francisco were certain there had been no survivors. Crippled beyond defense, aware of the danger from the submarine that had destroyed Juneau, and convinced there were no living sailors to rescue, the battered convoy faded on the horizon in search of safety.

Amazingly, there had been survivors, perhaps more than one hundred out of the 700 man crew. The violence of the explosion that had severed a 5-inch gun turret and hurled it more than half a mile, had catapulted the bodies of the sailors on deck through the air and into the ocean. Slowly they bobbed to the surface, breaking through a black layer of oil several inches thick to grab floating nets and other debris to cling too. Almost all were severely wounded, broken limbs with bones protruding, deep lacerations, and deadly internal injuries abounded. Across the waters could be heard the cries of pain, moans of despair, and shrieks of fear. Amid the cacophony of an unbelievable hell rose the voice of George Sullivan. "Al! Are you there? Red, where are you? Frank, Matt, please answer me."

Slowly the survivors began to pull the debris together, three donut-shaped life rafts and assorted floating nets. Wounded sailors desperately swam to join their fellows, and George continued to call out in agony, searching each face for the features of one of his brothers. Among the floating debris, he had found rolls of toilet tissue and quickly stripped away the oil-covered outer layers. It was a pitiful sight as he moved from raft to raft, net to net, slowly wiping the black oil from the faces of stunned and wounded sailors and peering into blank, frightened eyes for any sign of recognition. He was the oldest, the "big brother", and he had to find and help his younger brothers. They had to be there, somewhere. Despite his own wounds, he continued his fruitless search.

Throughout the day, many sailors died of their wounds. Others, too tired to find within themselves any reason to go on, slipped away from the nets, and sank beneath the black ocean swells to meet their former shipmates. As night fell, fewer than a hundred survivors remained. Throughout the night men died, at least one an hour. And throughout that long, cold night, all could hear the voice of George Sullivan continuing to cry out: "Al, Matt, Red, Frank? Where are my brothers?"

The breaking sunrise on the morning of November 14th brought some relief. Slowly the layer of oil began to thin and move away. The men crowded into the donut-shaped life rafts had stood in three feet of water throughout the night, their legs now were swollen and their bodies chilled. Others sat on the edges of the crowded rings, dangling their legs over the edges. As the water cleared, new dangers were revealed. Slowly the sharks moved in, hesitant at first. Then came screams as the first one, then another sailor was dragged from the nets and shredded by the predators of the deep. Some men were "fortunate" to lose only an arm or leg to the new enemy, others were dragged screaming completely beneath the surface to be devoured. New panic set it. George Sullivan continued to search for his brothers. He had to find them before the sharks did, offer the protection of a "big brother". To no avail, he searched and searched.

Towards noon a patrol plane appeared and dropped an inflatable raft. Seaman Joseph Hartney and Jimmy Fitzgerald braved the sharks in a desperate swim for the precious bundle. Amazingly they survived and returned to load the more severely wounded into the dry bottom of the new raft. The appearance of the plane provided more however than the raft, it signaled hope of rescue. But as the day dragged on, the hot tropical sun became yet another enemy, frying the flesh of men whose clothing had been literally ripped from their bodies by the explosion that destroyed the Juneau. Before nightfall, Hartney, Fitzgerald, and a badly injured officer left the group of survivors in a desperate effort to find land and mount a rescue effort.

By the fall of darkness on the second night, hope was vanishing for survival. Without food or freshwater, men began drinking saltwater and becoming delirious. Into the night the cries of despair continued, and even though that second night with all hope seemingly gone, George Sullivan continued to call out for his missing brothers. When dawn arrived on the third morning, it brought no relief. The pitiful remnants of the Juneau had to choose between a blistering sun that left their flesh as if it had been "shaved with a razor", or sharks that moved in with razor-sharp teeth.

Finally, the survivors chose to split into three groups. Lieutenant John Blodgett, one of only three surviving Juneau officers, set out with 7 of the strongest survivors on one raft. Nineteen other survivors set out in a second raft. The third carried almost a dozen survivors including George Sullivan and Allen Heyn. By the fourth day, George Sullivan became more and more delirious. He continued to cry out for his brothers to no avail, but his voice became weaker, his cries less frequent. As darkness fell over the South Pacific he turned to Allen Heyn and said he was going to swim to shore and take a bath. Quickly he stripped off his clothes and plunged into the darkness of the ocean, swimming desperately for an imaginary shoreline. From a distance, Allen Heyn could only watch helplessly the desperate struggle of George Sullivan against the elements. Then screams as the sharks moved in, the sound of thrashing in the water. Then, silence. In the depths of the South Pacific, George finally found his brothers: "We Stick Together".

Finally, the survivors chose to split into three groups. Lieutenant John Blodgett, one of only three surviving Juneau officers, set out with 7 of the strongest survivors on one raft. Nineteen other survivors set out in a second raft. The third carried almost a dozen survivors including George Sullivan and Allen Heyn. By the fourth day, George Sullivan became more and more delirious. He continued to cry out for his brothers to no avail, but his voice became weaker, his cries less frequent. As darkness fell over the South Pacific he turned to Allen Heyn and said he was going to swim to shore and take a bath. Quickly he stripped off his clothes and plunged into the darkness of the ocean, swimming desperately for an imaginary shoreline. From a distance, Allen Heyn could only watch helplessly the desperate struggle of George Sullivan against the elements. Then screams as the sharks moved in, the sound of thrashing in the water. Then, silence. In the depths of the South Pacific, George finally found his brothers: "We Stick Together".

Seven days after the sinking of the Juneau, on November 20th, an American destroyer found George Sullivan's raft. Allen Heyn was the only survivor. Lieutenant Blodgett succumbed to sharks only 4 hours before his raft was sighted and rescued on November 19th. Five sailors: Wyatt Butterfield, Lester Zook, George Montere, Frank Holmgren, and Henry Gardner, survived. Seaman Arthur Friend was the only member of the third raft to defeat the elements and be rescued. Jimmy Fitzgerald, Joseph Hartney, and the wounded Charles Wang reached land on November 21st. Of 695 sailors aboard the Juneau when the torpedo struck at 11:01 A.M. on November 13, 1942, only ten survived. Both of the Rogers boys, as well as all seven other sets of brothers, gave their lives that day.

Freedom Isn't Free

The story of the Sullivans is more than a true story about five brothers, it is the story of the courage and patriotism of an entire family. Despite the pain of their own tragic loss, Tom and Alleta Sullivan endured the invasion of their personal grief by a sympathetic Nation to promote the war effort. In April 1943 sister Genevieve enlisted in the Navy's WAVES. A year after the death of the Sullivan Brothers, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the launch of a new destroyer called "The Sullivans." Christened by the first mother since the Civil War to lose five sons in defense of freedom, The Sullivans served in World War II and Korea and is now on display in Buffalo, NY.

The story of the Sullivans is more than a true story about five brothers, it is the story of the courage and patriotism of an entire family. Despite the pain of their own tragic loss, Tom and Alleta Sullivan endured the invasion of their personal grief by a sympathetic Nation to promote the war effort. In April 1943 sister Genevieve enlisted in the Navy's WAVES. A year after the death of the Sullivan Brothers, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the launch of a new destroyer called "The Sullivans." Christened by the first mother since the Civil War to lose five sons in defense of freedom, The Sullivans served in World War II and Korea and is now on display in Buffalo, NY.

In 1995, a new Aegis Destroyer named U.S.S. The Sullivans were christened. It was commissioned two years later on Saturday, April 19, 1997. Among those in attendance was Lester Zook, one of Juneau's ten survivors. Three years later on November 12, 1998 (almost 56 years to the day after the sinking of the Juneau), Mr. Zook was tragically killed in an automobile accident.

In 1944. Hollywood released a movie titled "The Fighting Sullivans." The black and white film is shown on television from time to time and is available at most local libraries. We encourage you to take the time to view it.

In 1995, the story of the Sullivan brothers, their family, and the crew of the U.S.S. Juneau was published in the book, We Band of Brothers. Written by John R. Satterfield, it is a moving and historically accurate account of events far beyond what we can share in these web pages. We highly recommend it to all people, but especially to those who work with American youth, the heroes of tomorrow.

The Sullivan Brothers are not forgotten in their home town of Waterloo, Iowa. A special acknowledgment is made to the Grout Museum for their assistance in preparing these pages. They maintain the history and heritage of the Sullivan Brothers for future generations.

Special acknowledgment is also due to Mr. Mike Magee who contributed considerably to our story as well as to the book by Mr. Satterfield. There has been an unsuccessful campaign to get a U.S. Postage Stamp issued to commemorate the sacrifice of the Sullivan family. You can lend your support to the project by contacting Ron Glessner, a former crewman of the U.S.S. The Sullivans DD 537.

Finally, a special thanks to Kelly Sullivan Loughren. The deaths of the Sullivan brothers, more than 75 years ago, marked only the beginning of the sacrifices made by the Sullivan family. In the face of such tremendous loss, one can only marvel at the continued service and patriotism of the surviving family. Kelly presently serves as a director for Region 4 of Friends and Family of the Congressional Medal of Honor.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED