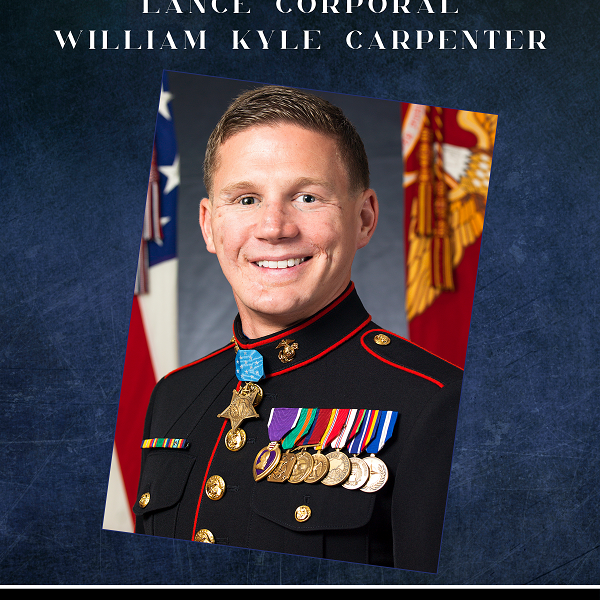

LCpl. William Kyle Carpenter

Lessons From Marine That Jumped on a Grenade

By James G. Fausone

Lance Corporal William Kyle Carpenter is one of two incredible Marines that performed similar acts of heroism that resulted in being awarded the Medal of Honor. Both men have their own stories but the lessons to learn are similar. What compels a young Marine to risk his life by jumping on a grenade to save his buddies? Is it their upbringing before the Corps or is it the training received while in the Corps? After reading about these men you will ask yourself, could I have done what they did? Was the reaction simply a result of training, instinct, or a higher power?

For action in 2010 in Afghanistan, Lance Corporal William Kyle Carpenter was the youngest Marine to ever receive the Medal of Honor. For action in Iraq in 2004, Corporal Jason Lee Dunham was the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor since the Vietnam War. Both made a decision to protect their fellow Marines by jumping on a grenade.

Lance Corporal William Kyle Carpenter

William "Kyle" Carpenter (born October 17, 1989) is a medically retired United States Marine who received the United States' highest military honor, the Medal of Honor, for his actions in Marjah, Helmand Province, Afghanistan in 2010. Kyle Carpenter was the youngest living Medal of Honor recipient at the time.

Kyle grew up in a loving household where spots, hard work, and dedication were supported. While this is a Marine that, as he says, "cuddled a grenade" and lived to tell about it, he is another example of how good men answer the call. His is also a story of overcoming the devastation of war with family love and hard work.

He was born in Mississippi and spent some time in Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. His family ended up in South Carolina, which he calls home. He had the typical "young boy in the south" upbringing. Football was his passion, younger twin brothers looked up to him, and he felt like he had a solid upbringing with loving parents.

Like many kids at the end of high school, their choices are college or military service. In March of 2009, he went off to Marine boot camp at Parris Island. He explained to VeteransRadio.net in a 2019 interview why he joined the Marines:

"William Kyle Carpenter: I wanted to do something bigger than myself. Regret and unfilled potential is, besides hand grenades now, my only two fears in life. I just wanted to do something that was bigger than any one individual and I wanted to do it and not have the fear of waking up one day when I had missed my opportunity and have regret about not joining and not committing myself, and now my body and my life, to something greater than myself or any one person or individual.”

On November 21, 2010, Carpenter's life changed forever.

"William Kyle Carpenter: Roughly, a day and a half to two days before, on November 19, myself and the rest of my squad moved to a village in a rotation south of the small patrol base that we had been living and operating out of for the first four months so far in our deployment. Looking ahead, we were over the halfway point and for anyone not completely familiar with how things work, combat zones are when other units are coming to relieve you. Before those next units come in and you go home, what you want to do is expand your presence from how you found it and took it over from the unit that you relieved. We went into Marjah. We wanted to push out and expand our presence. That helps not only to continue to push the enemy further out, but also makes things safer, more comfortable for the locals. Then once the threats are gone, people start coming out more, they want to take advantage and, hopefully one day be able to send their children to school and have paved roads and running water. Just pushing that out to create more and more stability.

We had pushed out to a village south of our position, and within the hour, very soon after we took over that compound, the first grenade attack came. For the next 24 to 36 hours, we were attacked constantly by AK47s, small arm fire, snipers and multiple attacks with hand grenades. When all was said and done, it was time a few days later for my squad after myself and many of my fellow Marines were injured to go back to the base where we had initially started out at. We were almost at 50% casualties and we had barely left our 4 walls of safety of the base that we were currently occupying.

The day I was injured, November 21, 2010, myself and a fellow Marine, one of the most amazing and greatest Marines that I had ever had the pleasure of serving with and someone I am thankful to call a best friend, Nick Eufrazio, we were on top of a roof together on post. Post is essentially, for those not familiar with military terminology, it’s a look out position. We were on this roof looking for more hand grenade attacks. Any attacks that might injure the Marines who are not vigilant and on watch and either cleaning their weapons, eating or resting inside the compound. We were at the end of our 4 hour shift, which was the afternoon of November 21st.

Unfortunately, I don’t remember anything in the moments leading up to that daylight grenade attack. The only thing I remember from the day before is that morning, rolling out of my sleeping bag around 7:45 or 8:00 am, we were getting attacked. It was a day break attack with AK47s. That had kind of become our alarm clock over there. I remember unzipping my sleeping bag and rolling out and kind of thinking, here we go, another day in Afghanistan.

Fast forward to that afternoon, and really the only thing I remember from that day and the attack is, after the grenade exploded, I remember physically how I felt. At first, I was extremely disoriented and I was reeling from the blast. I just felt that I had got hit really hard in the face and I was trying to put the pieces together. I was thinking, okay, I was in Afghanistan, the last thing I remember was on a roof, but what could possibly injure me this bad from a roof? Maybe I got off and went on patrol and I stepped on an IED? Maybe this is just the last thing I can remember. Those thoughts and me trying to put those pieces together was interrupted by the feeling of what I was thinking at the time to be, warm water.

It just shows you how much Marines love each other and how much we pick on each other because I was thinking, man, in this banged up and terrible shape and state that I am in, my buddies are still messing with me. The pieces quickly and unfortunately, fell into place and gave me the surreal realization that what I was feeling was not warm water, it was blood, and I was bleeding out very quickly.”

As reported by his squad mates, there was a grenade thrown up on the roof and instinctively, Carpenter covered the grenade to protect his squad mate and his body, Kyle's Kevlar took the brunt of this grenade explosion, which blew a hole through the roof. There was this amazing effort by his squad and the medics and everybody else to save his life as he is bleeding out. The resulting medevac, multiple hospital stops in Germany & Walter Reed Hospital, is reported in his 2019 book, "You Are Worth It: Building a Life Worth Fighting For."

Lance Corporal William Kyle Carpenter's Medal of Honor citation reads:

MEDAL OF HONOR ACTION DATE: NOVEMBER 21, 2010

CITATION

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as an Automatic Rifleman with Company F, 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, Regimental Combat Team 1, 1st Marine Division (Forward), 1 Marine Expeditionary Force (Forward), in Helmand Province, Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom on 21 November 2010. Lance Corporal Carpenter was a member of a platoon-sized coalition force, comprised of two reinforced Marine squads partnered with an Afghan National Army squad. The platoon had established Patrol Base Dakota two days earlier in a small village in the Marjah District in order to disrupt enemy activity and provide security for the local Afghan population. Lance Corporal Carpenter and a fellow Marine were manning a rooftop security position on the perimeter of Patrol Base Dakota when the enemy initiated a daylight attack with hand grenades, one of which landed inside their sandbagged position. Without hesitation, and with complete disregard for his own safety, Lance Corporal Carpenter moved toward the grenade in an attempt to shield his fellow Marine from the deadly blast. When the grenade detonated, his body absorbed the brunt of the blast, severely wounding him, but saving the life of his fellow Marine. By his undaunted courage, bold fighting spirit, and unwavering devotion to duty in the face of almost certain death, Lance Corporal Carpenter reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service.”

Kyle Carpenter's story is of recovery, struggle, redemption, and perseverance. Today, Carpenter may be one of the most grateful and well-adjusted Medal of Honor recipients in recent history. This again highlights a strong supportive family structure he had before joining the Marines and its impact on his recovery. He explained to VeteransRadio.net in 2019:

“William Kyle Carpenter: Wow, where to start. …. On a foundational level, just to have someone beside you that says, hey, I support you, I love you, and I’m here for you. Veteran or not, military or not, injured or not, just as a person and as a human being, to have people and my family, and yes, the amazing staff at Walter Reed. Just from the moment I woke up to have the love and support I did. It was hard for me almost to not stay positive. I woke up and I was alive. Incredible, amazing Step #1. I just could not believe it because I truly thought when I felt myself bleeding out, that that was it.

Then I wake up to this bonus round. Yes, I’ve been fighting for my life. It was so hard and terrible to breathe through a tube for months. It took me a long road to recovery to get back on my feet. At the foundation of it all, to just be loved and supported and have a helping hand around my shoulder was enough to help me be able to continue to knock out the baby steps and strive to reach that potential in whatever recovery I was in.”

Here is this badass Lance Corporal Marine, the guy jumps on a grenade and one of the things that really helps him get through the down times is this fluffy white 9 1/2 pound dog named Sadie.

"William Kyle Carpenter: Thankfully, there are a lot of dog lovers out there so if I’m being judged … Sadie was like any great dog. After I spent my initial life-saving three months at Walter Reed, the casualty rate coming in was astronomical. At one point, there were hospital beds in the hallways at Walter Reed so when it came time for me to still need to be taken care of medically, but also I didn’t have to stay in-patient every second of every day, I was allowed by the military and the staff at Walter Reed to go home and recover until that following September. I got done at Walter Reed at the end of January, but I got to home for seven months and recover. All I could do was lay on the couch and I had the tough job of eating mom’s amazing homemade southern-cooked food all the time. I just lay on the couch. Sadie likes her personal space and doesn’t like to be bothered all the time if she is in that mode. I think she knew. She sat there with me every second of every day for those seven months and helped me get better and she’s the best.”

Naturally, Carpenter felt he was damaged goods and that nobody was going to love him. You have to work through the recovery both physically and mentally after you cuddle a grenade.

"William Kyle Carpenter: That is a great question and I’m glad you brought that up because out of everything that I talk about in the book, this one extremely low moment was not only a defining moment in my recovery but my life.

It was very shortly after I had left the hospital at the end of February, so this was spring 2011. I think, up until that point, through all of the pain, the time at Walter Reed, just the surgeries, I think that I was strong and as good as I was, I pushed as hard as I did because aside from all of my physical stuff and my injuries, it was equally as much, if not more, an emotional and mental burden on me knowing that my family and my parents, I knew how heart wrenching it had to be for them. So I tried not to show anything but positivity. My dad said he never believed me but I always would say I’m not in any pain because I didn’t want to hurt them anymore.

But I was at home, in the spring of 2011, it was about 10 o’clock at night, and it was a very movie-like setting, the lights were kind of dim, mom was the only one still up, and I was in the kitchen by myself and I hadn’t had any of my nerve surgeries on my arm, I could barely operate enough to make a bowl of cereal. I finally get this bowl of cereal made and I try to start eating it. I can barely hold the spoon and that’s a challenge. Up until a couple of weeks before this point, my mom was still brushing my teeth, putting on my underwear, tying my shoes. My doctors, I can’t even express how amazingly they rebuilt and put my face and my jaw back together, but the grenade blew most of my teeth out on the bottom and some on the top, and really just completely destroyed my entire lower jaw and part of my upper jaw, pretty much everything from my eye socket down.

I’m sitting here trying to eat my cereal with no teeth. I can’t feel my chin because my nerves are severed. I noticed milk is all over my face, dribbling down my chin, and something inside me completely broke.

I started crying harder and harder until I was borderline hysterically crying. My mom rushes in and her first thought is, of course, I’m in pain and what is wrong? I just looked at her and said, “who is ever going to love me again?”

Yes, it was a low moment and so hard. At the time, I regretted saying it because I could see that it absolutely tore her in two. My book is essentially lessons that over time, and reflection, and personal growth, I realized a life lesson that I wanted to convey to people.

Now looking back, I’m so thankful for that moment, that low, terrible moment at the kitchen counter because I realized that as upset and down as I was, that I could either get up, take one small step and put one foot in front of the other, and continue to push through not only my recovery, but the rest of my life and make the best with the cards that I have been dealt. Or, the only other option that I had, and that we have in life, is when we are knocked down… I could have sat at that kitchen counter for the rest of my life.

I’m thankful I made the choice that I did and I didn’t know exactly what I was doing at the time, all I knew was that I could have got up and made the best of it and pushed forward. Or, I would have stayed right there, down and out, crying and trying to eat that bowl of cereal for the rest of my life. The turning point in my recovery, and really where I have decided that I was always going to move forward and never look back, and what happened, happened, is right there sitting at that kitchen counter.”

Amazingly, Kyle lived after his selfless act of covering a grenade. How you are going to live after a tragedy is a choice. He had to decide how to live and if he was going to hide his scars.

"William Kyle Carpenter: At one point in my recovery, I tried scar revision therapy. After I got out of surgery, the doctors kind of said, hey, we have this laser treatment and we can smooth a lot of these scars out on your face. I was there for three years. It was there and available, so I said, why not, I’ll try it. I came out of that and my face was swollen. It really looked like I stuck my head in a beehive. I got back to my room and I was looking at myself in the mirror and I had a “what am I doing” type moment.

I asked that to myself for two reasons. One, trying to smooth out the scars on my face, would that be possible? Yes, with a certain number of treatments, it would probably make me a little bit prettier. It would be hard, but it might make me look a little bit prettier. Then you go down and you get to a massive scar on my neck that goes from my ear all the way to the other side of my neck. My trach scar … then we don’t have enough time the rest of the day to talk about the scars from the neck down.

I tell people to own their scars, who am I if I sit here trying to get scar revision therapy and trying to get rid of the things that I am telling people to be proud of and to own?

Through that thought process, I kind of solidified in my thought process that as far as scars, they are really beautiful. And people may see them as physically different or physically ugly, but scars show our physical representation that you have not only lived but you’ve been knocked down, or you’ve been injured, or you bled, or you had these hard times.

Scars can be absolutely just as mental and emotional, as physical. Those are much tougher, obviously, because people can’t see them for a lot of time, and people might not want to talk about them. But as far as my physical scars, and people’s physical scars, be proud of those. They show that you have lived life and you pushed through whatever gave you those scars. Now, you might have a scar but you have the knowledge, experience, more reliance, and perseverance when the next challenge or the next life obstacle comes your way. Above that, not only for yourself, but you can connect with other people who have struggled.

The struggle was kind of my lightbulb term. When I realized that the angle that I could take is struggle because everyone on this planet, that is that common thread through us all. Mental, physical, and emotional. Scars – own them. Be thankful for them because you are still living and you are still breathing. You are better and stronger than you were before.”

Sacrifice often leads to struggle. Carpenter's sacrifice led to immense pain, surgeries, and scars. He and his family had to work out these struggles. But they had the joy that he lived and was now again living. He embraced his scars.

These men - LCpl. William Kyle Carpenter and Cpl. Jason Lee Dunham - who cuddled a grenade, acted in a way that is beyond belief. Such acts of valor often come with the cost of life. On occasion, the men survive and have to live with the resulting scars and struggles. They remind us of the importance of family and foundational values. We can learn from them both in their acts of heroism but also in putting the pieces of life back together.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment that you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com

Listen to Veterans Radio's interview with William K. Carpenter

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED