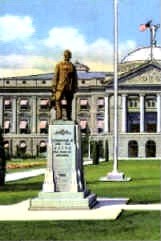

Frank Luke

Frank Luke

The Balloon Buster

Second Lieutenant Frank Luke nursed the engine of his French Spad-13 as twilight was falling over the field at Coincy near the Western Front. He was late again, the rest of the planes from his squadron had returned much earlier from their evening protection patrol for two photographic Salmsons from the 88th squadron. So, what else was new? Luke was always returning late, and usually alone, after being separated from his squadron on most of their missions.

Second Lieutenant Frank Luke nursed the engine of his French Spad-13 as twilight was falling over the field at Coincy near the Western Front. He was late again, the rest of the planes from his squadron had returned much earlier from their evening protection patrol for two photographic Salmsons from the 88th squadron. So, what else was new? Luke was always returning late, and usually alone, after being separated from his squadron on most of their missions.

The 16-plane patrol including three from Luke’s 27th Aero Squadron had left shortly after five o’clock that evening on what would be a frustrating, but uneventful patrol. Shortly after takeoff, the American pilots began dropping out of formation one-by-one as they struggled with the temperamental engines of their Spads, (most of them less than two weeks old). In very short order, the only airplane still flying was that of 27th Squadron Commander Major Harold Hartney.

Hartney was furious as he headed back to the airfield at Coincy. These new Spads were proving to be an airborne disaster. Mechanical problems were knocking far more of his planes out of the sky than the Germans were. An Ace with five kills while flying with the British Royal Air Force before transferring to the new American First Pursuit Group, Hartney was one of the few experienced pilots in the air that day. Despite his experience, he never noticed the four enemy aircraft that slipped up on his tail or heard the rattle of machinegun fire from the one other Spad still flying. He didn’t even know he had an ally behind him, single-handedly taking on four enemy planes, as Hartney banked and headed safely home to land at Coincy.

On the ground, thirteen pilots paced, cursed, and kicked the tires of their Spads while denouncing the day the “lumbering bricks” had replaced their semi-trustworthy French Newports. To make matters even worse, a fourteenth pilot had made it back in his faltering Spad, but would never be going home. As Lieutenant Ruliff Neivius came in at 6:45 he misjudged his landing, crashing to his death. The one moment of relief came when the pilots, fearing the loss of their commander when he had not returned, saw Major Hartney’s Spad land and taxi to join them. That left only one airplane unaccounted for, the Spad flown by Lieutenant Frank Luke of Arizona. Not to worry…Luke was always late! And if worse came to worse, none of them would shed any tears over the grave of the brash young rookie who had been with the 27th for only three weeks. Already the Arizona cowboy had worn out his welcome.

Coming in above the field, Lieutenant Frank Luke felt the cool evening wind whip through his long blonde hair as he banked towards the airstrip. He knew the guys below didn’t like him, in fact, had gone out of their way to shun him. They called him The Arizona Boaster because of his brash, matter-of-fact talk of what he would do when at last he saw combat. Perhaps on this evening, in the early stages of Frank Luke’s career as a fighter pilot, he still held some hope that he could win them over. It was dangerous work, flying almost daily in skies patrolled by German airmen intent on shooting you down. It was doubly difficult to come back home and find that even your allies were your enemies.

Luke gunned his engine, tipped his wings, and leveled for a landing. He was used to being cheered for his guts and accomplishments. Back in Arizona, where Luke had been an athletic star in track, baseball and football at Phoenix Union High School, the 5’9″, 155-pound young man would never quit. Starting tailback and captain of his football team, he played with an energy and abandoned far beyond his size. When he broke his collar bone in the first half of one football game, the crowd cheered at the opening of the second half to see the injured but determined young man come back in to ignore his pain and finish the game. On this day, Luke had finished the game once again, so let the cheering begin. With a loud whoop he stepped out of the cockpit and excitedly shouted:

“I got me a Hun!”

There were no cheers…only blank stares.

“You hear me? I got a Hun! There was four of them, right there coming in on the Major’s tail when I opened up. I got one and sent the others hightailing it for home.”

More dead silence followed. Then, one of the pilots looked Luke in the eyes and asked, “Who saw you shoot down this plane?” More dead silence followed.

No one, not even Major Hartney, had seen Luke’s purported battle with the German airplanes. With grunts of disdain and only half-concealed words of contempt, the pilots of the 27th Aero Squadron turned to head for the mess hall. The Arizona Boaster was not only a loud-mouth, he was now a bald-faced liar! There would be no cheers for Frank Luke on this day

The Western Front – 1918

Three years of warfare had given the Allies little hope against the Central Powers when at last the United States entered the war and began sending soldiers to Europe. By May 1918 however, only about 500,000 of what would eventually be a force of 1.2 million combat troops had arrived in France. The American presence that Spring gave the Allies little more than a hope for change, and some badly needed moral support.

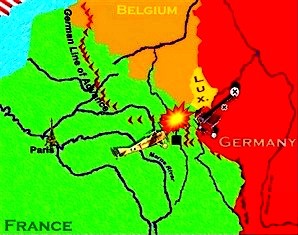

On March 21 the Germans launched a major offensive to pre-empt any success the newly arrived American doughboys might afford, shifting some 40 divisions to the effort along the Western Front. By May they held a line only 56 miles from Paris, and the French were reeling from the series of sudden attacks. Poised to deliver a crushing blow, the Germans pushed their advantage in the Marne region on May 27. The following day American troops of the AEF’s First Division met the Germans at Montdidier, repulsed their attack, and then pushed on to capture the strategically located town of Cantigny. It was the first major American action of the war, and the first victory, despite American losses of 187 killed in action, 636 wounded.

On March 21 the Germans launched a major offensive to pre-empt any success the newly arrived American doughboys might afford, shifting some 40 divisions to the effort along the Western Front. By May they held a line only 56 miles from Paris, and the French were reeling from the series of sudden attacks. Poised to deliver a crushing blow, the Germans pushed their advantage in the Marne region on May 27. The following day American troops of the AEF’s First Division met the Germans at Montdidier, repulsed their attack, and then pushed on to capture the strategically located town of Cantigny. It was the first major American action of the war, and the first victory, despite American losses of 187 killed in action, 636 wounded.

German forces continued their Spring offensive, driving through the Belleau Wood in the first days of June. A full American division was moved up to stop the German Seventh Army. The bloody battle of Chateau-Thierry was the worst fighting for American soldiers since the battle of Five Forks in the Civil War, much of it borne by the men of the 5th Marines who struggled with the enemy in often hand-to-hand combat. Fighting in the Belleau Wood continued throughout the month of June until the American forces launched their final assault on June 25. Despite nearly 10,000 casualties in the AEF’s Second Division, the brave marines and doughboys had defeated four enemy divisions.

Throughout this period, aviators from both sides slugged it out in the skies. On April 21 with their Spring Offensive one-month-old, the German “Ace of Aces” Baron von Richthofen was killed after 80 victories for the homeland. One week later, Lieutenant Eddie Rickenbacker of the 94th Aero Squadron shot down his first enemy airplane. On May 19, just one week before the first American victory at Cantigny, Allied Ace Raoul Lufbery was shot down. On May 30 Lieutenant Rickenbacker downed his fifth confirmed enemy aircraft (he had at least two unconfirmed kills), becoming an Ace for his own 94th Aero Squadron. Throughout the period, a young Second Lieutenant named Frank Luke was sitting out the war in combat flight training at Issoudon, followed by gunnery school.

On June 1, the 27th Aero Squadron became operational in the relatively quiet Toul sector of France as a part of the 1st Pursuit Group. The 1st PG consisted of four squadrons, populated by veteran pilots and commanded by respectable leaders.

|

||||||||||

| . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| Aero Squadrons | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

*In the closing weeks of the war the 185th “Bat” Squadron, a night-pursuit squadron, was added to the 1st PG

The day before the 27th Aero Squadron became operational, 21-year old Frank Luke got his first assignment. To him fell the inglorious task of being a ferry pilot for American Aviation Acceptance Park No. 1 at Orly. His duties consisted of flying new aircraft to the aerodromes on the lines, to be used by the men who were fighting the air war. His return trips consisted of nursing badly shot up airplanes back to Orly for repairs. These were bullet-riddled with windscreens shattered and fabric torn. All too often bloodstains and pieces of human tissue were spotted throughout the cockpit, grim reminders that aerial combat was not a game.

On July 20, the Eagle Squadron fielded a 5-plane patrol from which only three returned. Three pilots, including Second Lieutenant John MacArthur (6 victories and the 27th’s only Ace) and Zenos Miller (4 victories), were wounded and shot down. The third pilot wound up in a hospital in France, leaving the squadron very short on manpower. Five days later a group of replacements received orders for the 27th Aero Squadron. Among the young pilots was the brash Arizonian Lieutenant Frank Luke.

July 25-26, 1918

It was close to midnight when the seven pilots arrived at the 27th Aero Squadron’s headquarters near Saints. Of the seven men, all were rookies but one, Lieutenant Donald W. Donaldson who was transferring from the 95th. The move took the young rookie would-be fighter pilots from an insulated world that saw combat only through the tales of others, to the real world of blood, horror, and sudden death. Squadron commander Major Hartney was quick to point this out the following morning in his welcome speech to the new recruits:

“You are in the 27th in name only. When you have shown your buddies out there that you have guts and can play the game honestly and courageously, they’ll probably let you stay. You’ll know without my telling you when you are actually members of this gang. It’s up to you.

“If you survive the first two weeks you’re well over the hill. I’m not trying to discourage any of you, but you may as well know what you’re up against from the first. Some of you are certain to be washed out during the first two weeks. If you get through that period safely and your own personal god continues to strap himself in with you, you’ll probably accomplish things. That’s all, gentlemen.”

Throughout his brief speech, Hartney couldn’t help but notice one of his rookies. “In a way, I resented his attitude,” Hartney later said. “He seemed to be saying, ‘Don’t kid me. I’m not afraid of the bogey man.’ When I had finished talking, he was grinning. That ruffled me, too.”

On his first day with the squadron, Frank Luke was already off on the wrong foot, and with the squadron commander no less.

The fact that Major Hartney’s welcome speech dealt more with “belonging” than with fighting is no mere coincidence. Hartney knew the men of his squadron well, knew that the word “fraternity” perhaps defined them more appropriately than the word “team”. His words were a cautionary note to the new pilots, designed to help them fit in.

The Good Ol’ Boys

Major Hartney himself wasn’t necessarily a member of the “Good Ol’ Boy” network, didn’t in fact, need to belong. He was the “Old Man”…the boss, and an experienced pilot with the title “ACE”, which in and of itself commanded some respect. Thirty years old when he commanded the squadron, he was older than any of his pilots by several years. After serving with the Royal Air Force, the Canadian-born aviator had assumed command of the 27th Aero Squadron in September 1917 when it was sent to Toronto to train for war.

When his new replacements arrived on July 25, they joined a squadron of 16 other men, three-fourths of whom had been together since the Kelly Field, Texas muster of the squadron on May 8, 1917. That dozen had been together through initial training, further training in Canada under Hartney, the long trip to Europe, and the early days of aerial combat during Germany’s Spring Offensive of 1918. They were a tight-knit group that knew each other well, had learned to trust each other and found unity in the things they had in common. One of the common denominators was that all had college educations, most from prestigious Ivy League institutions. Their enlistment in the Army’s Air Service had been for most of them, simply a move from one fraternity to a new one.

If the aerodrome at Saints had been a University Campus, the B.M.O.C. would probably have been First Lieutenant Alfred “Ack” Grant. During his tenure at Kansas State Agricultural College, Grant had served in the campus military cadet corps. Though not necessarily impressive in either resume or combat flight, Grant had a little more military bearing than the others and tended towards leadership. He also had two confirmed victories in combat.

In contrast was the hard-working Lieutenant Jerry Vasconcells, born and raised in the small Kansas town of Lyons, then working his way through an education at the University of Denver in Colorado. (With one confirmed victory when the replacements arrived, Vasconcells would go on to become Colorado’s only ace of World War II, yet vanish into obscurity in his home state.) The military bearing that marked Grant, was more than made up for by the engaging personality of Vasconcells.

Neither Grant nor Vasconcells had ever attained the Ivy League status held by most of their contemporaries, but both were able to find their niche in the 27th Aero Squadron. The Good Ol’ Boy Fraternity consisted of a dozen young men in their early twenties, who had traded their fraternity sweaters for a pair of goggles and their walking sticks for ailerons. It was into this mix that the green but eager young replacements were thrown.

The Arizona Boaster

Asking the 21-year old kid from Arizona to become a part of this fraternity was akin to trying to mix oil and water.

Asking the 21-year old kid from Arizona to become a part of this fraternity was akin to trying to mix oil and water.

To begin with, though a college education was required even among the earliest US Army aviators, no one knows when, where, or even if Frank Luke attended college. He graduated from Phoenix’s Union High School somewhere around 1915-16, where yearbooks described him as “Too happy-go-lucky to know his own talents.” What he did in the two years following is not generally known. If he did not attend college, he must have pulled some fancy strings to get into pilot training.

Frank, Jr. was born and raised in Arizona Territory, in its own way “the new kid on the block” having only achieved statehood six years before Luke arrived in Europe. Frank Luke, Sr. was a respected man in the community, a shopkeeper before turning to politics where he served as the Phoenix City assessor, Maricopa County Supervisor, and finally as a member of the Arizona State Tax Commission. In 1917 the family patriarch moved his family (there were nine children with Frank, Jr. squarely in the middle), into a new home at 2200 Monroe Street, one of the city’s finest homes in one of its best neighborhoods.

In September 1917, Frank, Jr. trained at the School of Military Aeronautics at Austin, Texas where he managed to get orders for flight school. On a two-week leave that fall he returned to Phoenix to visit the new family home on Monroe Street. During that brief period, he was rushing off to watch a football game one night when his mother called for him. Tillie Luke was busily turning the new house into a home and wanted her son to plant some lily bulbs before he left. Hurriedly Frank dug up a few holes, randomly placing the bulbs, covered them neatly, and rushed off to catch his game. It was a simple act, one of those common occurrences in life that, in Frank’s case, would ultimately add a touching appendix to his legendary life.

On January 23, 1918, he got his wings and a commission as a second lieutenant at Rockwell Field in San Diego. After another leave, he was off to catch his ship in New York and find his war.

August 1, 1918

When Frank Luke and the other replacements arrived at 27th operations on July 25, the squadron’s only Ace was Commander Hartney, who had got his kills flying with the R.A.F. No other pilot in the squadron had more than two victories.

In that last week of July, Hartney wasted no time getting his new pilots in the air, often leading them himself on combat patrols. Despite almost daily flights, not a single combat report was filed by any of the pilots. The mission on August 1 would change all that and give the new pilots a rude welcome to the unfriendly skies.

The early dawn mission was an 18-plane protection patrol for two Salmsons darting in and out of German territory to photograph enemy positions. After three successful passes, on the fourth incursion, the American planes were jumped by eight Fokkers of the Richthofen Flying Circus. In the initial attack, Lieutenant Charles Sands went down in a fatal dive…dead his first week on the front. A short time later he was joined by Lieutenant Oliver Beauchamp who had arrived with Sands. Neither man had survived Hartney’s “two-week” benchmark. But the rookies would not be the only casualties on the most disastrous day the Eagle Squadron would suffer in World War I. A charter member of the 27th, Lieutenant Jason Hunt was also killed in action.

The Eagle Squadron pilots claimed six victories that day, three of them by Lieutenant Donald Huston who now had raised his total to 4 victories and was close to becoming the only ace in the Squadron. Jerry Vasconcells also got a victory, bringing the future Ace’s total thus far to 2 confirmed victories. But three more 27th Squadron pilots also fell that day, bringing the American losses to six. Veteran Lieutenants Richard Martin and Clifford McIlvaine and rookie Frederick Ordway were shot down in enemy territory and captured. With a 33% casualty rate for the day, Major Hartney’s squadron was decimated and would not fly another mission for more than a week. Frank Luke had missed the battle due to engine problems.

It was in the days following the August 1 disaster that the 27th Aero Squadron started getting its new Spads to replace the aging Neuports. Though the Spads became popular with the fliers of the 94th and 147th Squadrons, the men of the Eagle Squadron hated them for their unreliable engines. On August 9 a 13-plane reconnaissance flight was mounted to boost Hartney’s pilots from the doldrums the August 1 disaster had dealt them. Four of the Spads had so many problems they had to make forced landings, including the one piloted by Frank Luke. Luke’s was the only of the four Spads that was salvageable.

The squadron continued flights over the coming days, finally engaging in their first combat action in two weeks on August 14. Though neither side scored a victory, the bullet holes in the canvas of the returning Spads proved that the 27th Aero Squadron was back in the battle. It was a badly needed morale boost, especially in view of the recent victories of now ACE Eddie Rickenbacker and the “Hat in the Ring Squadron”. The competition was fierce among the squadrons of the 1st Pursuit Group, but it seemed that the 94th was the perpetual front-runner.

From the arrival of Frank Luke on July 25 until his purported victory on August 16, the only victories scored by the entire 27th Aero Squadron were the six enemy planes claimed in the August 1 battle.

August 17, 1918

Frank Luke’s victory the previous day had not only failed to earn him the respect of his fellow pilots, it had the opposite effect. Despite the disbelief of the others, Lieutenant Luke filed his combat report and then went into isolation. Major Hartney seemed inclined to believe Luke’s claim, but among the Good Ol’ Boy network, there was only derision. For his unauthorized flight over the lines, Luke was grounded for three days and ordered to act as airdrome officer from 4 a.m. until 10 p.m. each day. Two of the rookies stood with Luke, Lieutenant Joe Wehner who had arrived with Frank on July 25, and Lieutenant Ivan Roberts who had joined the 27th in May. Beyond those two, however, Luke was a man alone.

Luke’s misfortune took a devilish turn on August 21 when orders arrived assigning Major Hartney to the post of Group Commander. Though Hartney had been more than miffed by Luke’s reaction to the welcome speech, even more, upset at the young man’s demeanor on the ground, he seemed to have an almost paternal understanding for the troubled young flier. After the war, Hartney would describe Luke as: “Bashful, self-conscious, and decidedly not a mixer…his reticence was interpreted as conceit. In fact, this preyed on his mind to such an extent that he became almost a recluse, with an air of sullenness, which was not that at all.”

Other pilots recall Hartney saying of Luke during the war: “He was the damnedest nuisance that ever stepped on to a flying field.”

Whatever Hartney’s true feelings, he at least was the one person in authority who could view Luke rationally, to the point that the other pilots ribbed their commander by referring to Luke as Hartney’s “boyfriend”. Hartney’s promotion left a void in the Eagle Squadron’s command structure that was quickly filled by Lieutenant “Ack” Grant. There would be no slack cut on behalf of Frank Luke in the days ahead. After one of his solo missions, Grant called him in to straighten him out. “I don’t know what you got away with under Hartney,” he told Luke, “But things will be different now. You will get with the program, fight this war by the book, or so help me I’ll have those shiny wings of yours.” Then, to emphasize his point, he made Luke the engineering officer…one of those dreaded details that consisted of menial tasks and long hours.

In the weeks that followed, Luke avoided the other pilots when he could, taunted them to fisticuffs when he could not. To pass the daylight hours he began honing his marksmanship. On a motorcycle he would bounce across the field at Saints with a pistol in each hand, firing simultaneously at targets mounted on nearby trees. With his mechanics, he would work on his Spad, honing the engine and tightening turnbuckles to try and increase its maneuverability. The most hated man in the U.S. Army Air Service didn’t seem to care if no one liked him. He was a loner…and had carried that reputation since his first day on the lines.

In the weeks that followed, Luke avoided the other pilots when he could, taunted them to fisticuffs when he could not. To pass the daylight hours he began honing his marksmanship. On a motorcycle he would bounce across the field at Saints with a pistol in each hand, firing simultaneously at targets mounted on nearby trees. With his mechanics, he would work on his Spad, honing the engine and tightening turnbuckles to try and increase its maneuverability. The most hated man in the U.S. Army Air Service didn’t seem to care if no one liked him. He was a loner…and had carried that reputation since his first day on the lines.

That, at least, was how the legend of Lieutenant Frank Luke would be told for future generations. It is probably a very inaccurate explanation for the complexity of the young aviator’s psyche.

Of course, Luke had become known for weeks as the pilot who was always dropping out of formation to strike out on his own. The fact of the times was, dropping out of formation was a regular occurrence for all pilots of the 27th, more so after the arrival of the hated Spads. If another pilot developed engine trouble, dropped out, and made a forced landing, it was chalked up to mechanical problems. Where Luke was concerned, mechanical problems became an excuse for those who disliked him for his boisterous talk, to label him independent, rebellious against authority, and a loner.

Luke was independent and quick to ignore orders if he had a better idea. But it is safe to assume that prior to August 16 the Arizona cowboy had still hoped to win over his fellow pilots. Had he not expected his victory to earn him a new niche in the Squadron, the negative reaction would not have affected him so deeply. In the weeks after his first victory, Luke did drop out often to visit with the French fliers. Everybody needs someone, and Frank Luke found his only human solace among these French pilots who seemed to welcome his company. Similarly, were Frank Luke a true loner, he would never have developed the friendship that would help him generate a legend and ultimately turn him into a “madman”.

The German Spy

When the new replacements arrived at the 27th Aero Squadron on July 27, one of the enlisted men, Corporal Walter “Shorty” Williams wrote in his diary: “We suspect a couple of German spies are in our outfit.” Somehow, the reputation of Lieutenant Joseph Frank “Fritz” Wehner had preceded him to the Western Front in France.

When the new replacements arrived at the 27th Aero Squadron on July 27, one of the enlisted men, Corporal Walter “Shorty” Williams wrote in his diary: “We suspect a couple of German spies are in our outfit.” Somehow, the reputation of Lieutenant Joseph Frank “Fritz” Wehner had preceded him to the Western Front in France.

Wehner was indeed German by heritage, the American-born son of immigrant Frank W. Wehner who had risen from poverty to the American Dream in Everett, Massachusetts. The elder Wehner’s sons had benefited from the Land of Opportunity and had taken advantage of every opportunity presented to them. Like Frank Luke, Joe had been a stand-out athlete in high school, captaining the 1913 Everett High School football team to an undefeated season. When he graduated in 1914, his football prowess netted him a two-year scholarship to the Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, where he earned honors as a member of the Kappa Delta Pi fraternity.

Joe Wehner was indeed the All-American young man, bright, athletic, and dedicated to all things well. Upon finishing his education at Exeter, he went to Berlin as the private secretary to an official in the Young Men’s Christian Association. There he reportedly worked to help Allied prisoners of war until April 1917 when the United States severed diplomatic ties with Germany. He promptly returned home to learn that his surname made him suspect as an enemy spy, allegations further enhanced by his time living in Berlin.

Such charges were not uncommon during World War I, even famed race driver Eddie Rickenbacher (he changed the Arian spelling to Rickenbacker during his military service, partially due to this prejudice), had been suspect and repeatedly tailed and investigated…even after joining the Army and going to Europe with the A.E.F.

Wehner joined the Army Air Corps during the summer of 1917 and was preparing for war at the Aviation Corps in Bellville, Illinois when the F.B.I. launched an investigation on October 8th. On October 14th the cadets received Sunday passes, and while they were out of the billets the assigned agent went through Wehner’s belongings. Nothing incriminating was found, but the suspicion continued to hang over Joe Wehner for the rest of his military career.

As Joe was preparing to leave New York for duty in France in January 1918 he was again detained. It took a judge’s order to free him so he could the February departure.

When Joe joined the 27th Aero Squadron, the suspicions followed him and denied him close friendships save for Frank Luke, a fellow first-generation German-American with a personality as different as could be scripted as that of Joe Wehner. Luke seems never to have suffered much of the suspicion endured by Rickenbacker, Wehner, and others (perhaps his father’s political influence back in Arizona spared him); but among the pilots of the Eagle Squadron Luke’s friendship with the spy, Wehner made him guilty by association, and gave Grant and his buddies even more fuel to fan their hatred of the boisterous Arizonian.

St. Mihiel

After August 16 the flights by pilots of the 1st Pursuit Group were all routine. Rarely did the pilots even see an enemy plane, and not a single victory was scored by any of the four squadrons. It was just as well. Colonel William Billy Mitchell was gearing up for the greatest American air show of the war, and until the opening guns, he wanted his aerial armada well concealed.

After August 16 the flights by pilots of the 1st Pursuit Group were all routine. Rarely did the pilots even see an enemy plane, and not a single victory was scored by any of the four squadrons. It was just as well. Colonel William Billy Mitchell was gearing up for the greatest American air show of the war, and until the opening guns, he wanted his aerial armada well concealed.

On August 29 the Eagle Squadron got orders to move to a new aerodrome at Rembercourt near the Marne River. From the small grass field hidden by a ring of trees and artificial camouflage, the 1st Pursuit Group would be launching support for the first American offensive of World War I near the town of St. Mihiel.

The 27th began moving on September 1 and completed the transition on September 6, one week before the opening salvos of the offensive were scheduled to begin on September 12. For air power, it would be a defining moment if Colonel Mitchell could pull it off. For months the Colonel had argued for a unified aerial role in the war, and the St. Mihiel offensive would give him that moment. Half a million American soldiers and Marines, supplemented by 110,000 French, were poised to strike at eight German divisions along the line from St. Mihiel. Mitchell himself would command more than 500 fighters, observation, and bomber aircraft in support of the offensive.

A key role for the fighters would be to deny the German tacticians intelligence information on Allied troop movements. If the enemy did not know the Allied strength, the position of its elements, the location of artillery units, and the movement of troops, the offensive might well be a great success and turn the tide of the war once and for all. Such information could only be denied if the fighter pilots could somehow keep the German observation balloons out of the sky.

Drachen Observation Balloons

Perhaps no other type of aircraft was as important to either side during World War I than the large observation balloons…called “Drachen” by the Germans and “Sausages” by the Americans. From a well-placed balloon near the front lines, an observer could watch enemy troop movements and direct deadly and devastating artillery fire with pinpoint accuracy. Where a well-placed machinegun might kill dozens of soldiers, a bomb perhaps even a hundred, a good balloon could account for thousands of deaths in a matter of hours. To the infantryman struggling to survive the horrors of war near the front lines, the appearance of an enemy balloon rising on the horizon was perhaps the most dreaded of all sights.

Because of their great value to warfare, both sides took extreme efforts to protect their balloons. Balloons were costly, scarce, and ultimately vital to success on the ground. One might think that the large orbs would be an easy target, stationary and far too big to miss. In fact, the most difficult victory for any flier on the Western Front was a balloon kill.

First and foremost, one could not bag a balloon without flying beyond friendly lines. Because they were stationary and tethered to the ground, they were hoisted only in an area controlled by their own forces. Furthermore, to protect the valuable balloons, anti-aircraft guns were concentrated around them on the ground, to fill the skies with deadly explosions (called “Archie” by the Americans). This heavy concentration of fire built a literal protective wall around the gas-filled balloons that would quickly destroy any would-be attacker in the sky. Finally, if any pilot was foolish enough to fly into the deadly curtain of anti-aircraft fire in his quest to destroy one of the prized balloons, there was usually a flight of fighter planes lurking above to sweep in and quickly destroy him.

Attacking observation balloons was a suicide mission, and every pilot knew that. If somehow a daring soul succeeded in his mission, and occasionally one did, the flaming eruption of the gas-filled airbag would all too easily engulf the attacker, taking him with it in its final throes of death.

“Any man who gets a balloon has my respect,” Lieutenant Vasconcells said as the officers chatted in the mess hall on the evening September 11. “I think they’re the toughest proposition a pilot has to meet. He has to be good, or he doesn’t get it.”

The other pilots nodded in ascent, adding their own small chatter to the subject of balloon hunting on the eve before the St. Mihiel Offensive was to begin. All participated in the discussion that is, except for Lieutenants Luke and Wehner, who sat by themselves in the distance.

September 12, 1918

September 12, 1918

At 5 a.m. the countryside near St. Mihiel reverberated with the sound of artillery as the first American offensive of World War I began. At Rembercourt anxious pilots wolfed down a quick breakfast, eager to become airborne and do their part to support the men on the ground. Their orders were to take to the skies to protect American balloons, but not to cross the trenches to engage enemy aircraft over hostile territory unless it was to conclude an engagement that had begun over friendly lines. Enemy balloons were to be identified, their location noted, but there was no standing order to attack beyond the trenches.

The early morning jitters were not helped by the steady rain that grounded all early aerial patrols for the 27th, and not until 7:30 a.m. did the squadron get any of its pilots in the sky. When at last the first Spads took off, the flight consisted of eight pilots streaking out towards…and (despite earlier orders) across, the lines of battle. Instead of flying in previously ordered three-man formations, all eight Spads hit the heavens like spreading shots.

One of the first pilots out was Joe Wehner. Shortly after takeoff he sighted a balloon near Montsec and fired 100 rounds into it. Quickly the German ground crew began winching the Drachen to the ground, and by the time Wehner had turned to make another run, the sausage was safely in its nest.

Lieutenant Leo Dawson sighted a line of enemy balloons but avoided them after duly noting their position. He did manage to strafe enemy trenches before landing to refuel at Erize. Less than three hours after the patrol began, he was back at Rembercourt where he was quickly joined by the 27th’s leading pilot Donald Hudson, who had seen no action other than to fire on a few vehicles in the city of St. Mihiel.

The day would not be totally uneventful for Allied fliers, however. First Lieutenant David Putnam of the 139th Pursuit Squadron was America’s top pilot with thirteen victories (8 of these flying with the French before transferring to the US Air Corps), a role he had held since the death of Lieutenant Frank Bayless back in June. On the opening day of the offensive, the American “Ace of Aces” was shot down and killed. Though Allied pilots would claim more than a dozen victories that the first day, Wehner was unsuccessful in his efforts to get credit for his balloon, leaving only one man to gain a victory for the entire 1st Pursuit Group. It would be the only confirmed balloon victory for any American pilot that day.

Lieutenant Frank Luke was near Marieulles, well out of his sector, when he saw the large black shape hanging steadily in the morning skies. Banking and turning 180 degrees, he climbed high above the Drachen, intent on fulfilling the statement he had made before he took off that morning, that he was going to bag a balloon.

High above now, he pushed the stick to the firewall, stood his Spad on its nose, and began his dive. The air around him shook with explosions as a curtain of Archie was hastily put around his target. Shrapnel ripped through the canvas of his wings and taught wires strained and snapped. Staring straight ahead he continued his dive, straight into the enemy balloon, opening up with his guns only when he was so close it would take great skill to avoid a collision. In the wicker basket hanging below the large black sausage, Lieutenant Willi Klemm tried to jump and parachute to safety, only to become fouled in the rigging. Below, the ground crew was anxiously winching the Drachen to its nest, as Luke banked to come back for another pass.

The skies continued to explode around the balloon and heavy machinegun fire tore through the skies, as Frank Luke made a loop and a half-roll to come in on his second pass. Moving even closer this time, he opened fire to rake a line of holes across the Drachen’s side. Still, the balloon refused to die as he hammered it with every round he could until both guns jammed. Circling for a third pass, he reached under his seat, pulled out a hammer, and slammed it against his guns to clear them.

Few pilots dared to attack balloons, much less make a second pass if the first attack failed. Frank Luke would not be denied. Climbing in a chandelle as he hammered at his guns to free them, he flipped over on his back and came in again, machineguns blazing at the rapidly descending orb. Suddenly a white cloud erupted upward, nearly engulfing his Spad as intense heat threatened to burn him alive. Coaxing all the RPMs his now ailing engine could muster, he burst through the explosion to see the enemy balloon collapse in a sea of flame. With a smile, he turned towards friendly lines.

The Spad’s engine sputtered and struggled as Luke watched the trenches pass below as he crossed into friendly territory, then landed near Dieulouard. American infantrymen rose from their positions, running in the direction of his battered plane. “What’s wrong, you hit?” asked one of the first to arrive.

“I’m okay,” Luke replied. “Did you see me nail that balloon over there?”

“See it?” The soldier responded. “How could any of us miss it? How you ever managed to get out of there….”

“Here, sign this then,” Luke interrupted as he held out a piece of paper and a pen to first one man, then another.” This time, no one would deny him his victory for lack of witnesses. Minutes later, a hand full of witness statements tucked in his pocket, Lieutenant Frank Luke climbed back in his Spad to return to Rembercourt. It was not to be. His engine had taken hits, along with the rest of his airplane, and would fly no further.

Luke spent the day and that night with the men on the ground, weary infantrymen, and the crew of an American balloon. Increasingly in the weeks ahead, he would finally find among them, the crowd that cheered when he came onto the field. These men appreciated the work he was doing, eliminating the enemy balloons that could bring sudden death upon them. These were the men who fought it out in the trenches, who struggled often in hand-to-hand combat, to defeat their enemy and to try and survive one more day. These men appreciated the Arizona flier’s tenacity, his raw courage to press his attack until he achieved victory. Without a doubt, they loved the show as well.

Lieutenant Luke didn’t return to Rembercourt until the following morning, and then only after hitching a ride in a motorcycle’s sidecar. It was Friday the 13th, but it would be a great day for American pilots…more than three dozen victories. The 103rd Aero Squadron alone scored 7 victories without a single loss. Among the four squadrons of the 1st Pursuit Group, however, not a single victory was recorded. Among the three-dozen Allied victories for the day, not a single enemy balloon victory was listed.

Luke fretted the time away, waiting for Spad No. 26 to be patched up. The mechanics towed it back to Rembercourt and shook their heads in amazement. “I’ve seen lots of planes come in,” the chief mechanic stated, “but when they come in this way, the pilot that flies ’em doesn’t climb out of the cockpit.” From the wings, more canvas had been shot away than remained. The top left wing was nothing but air, wire, and three stringers. The empennage was a sieve and a huge gash had been ripped through the pilot’s seat, less than six inches from where Luke’s body would have been seated.

Smiling, Luke stuck his finger in the hole in the seat and said, “You take care of the aircraft, chief. I’ll take care of myself. If I were going to get killed, this would have been it.”

If Frank Luke swaggered a little more than usual on September 13, he had good reason. His balloon victory was more than verified (though strangely enough it wouldn’t be officially credited for two weeks), and the condition of his Spad showed all too well the evidence of a man fearless in battle. His success did little to endear him to the rest of the squadron, more so in light of the fact that once again Luke had disobeyed orders, flying beyond the lines and poaching in another squadron’s area. It also probably helped little that in two days, the entire 1st Pursuit Squadron had scored no victories other than Luke’s.

Saturday the 14th would be a different matter, however, a banner day for the entire Group. Second Lieutenant Wilbert White of the 147th knocked down one enemy Fokker and one Drachen. Eddie Rickenbacker, the most popular pilot in the Hat in the Ring Squadron (he had become an Ace by the end of May but hadn’t had a confirmed victory in three months), brought down number six.

Luke left Rembercourt in a 12-plane patrol, armed for sausage. After his experience two days earlier, he had loaded his left machinegun entirely with tracers, hoping they would quickly ignite any balloon he encountered. Breaking away from the squadron with Lieutenant Leo Dawson, the two men attacked a balloon near Boinville. Luke’s stream of tracers crippled the balloon but failed to ignite it. In the first pass, the German observer leaped out to parachute to the ground, while Luke continued his dive to strafe the soldiers on the ground that were now pouring all their fire towards Dawson as he dived at the balloon. Lieutenant Thomas Lennon came in to deliver the coup de grace, the balloon collapsing slowly to the ground but never erupting.

The fate of the German observer who had parachuted to safety gives a unique insight into Luke’s attitude towards his war at the time. Later asked why he hadn’t strafed Sergeant Muenchhoff of German Balloon Company No. 14, Luke replied: “Hell, the poor devil was helpless.” For Frank Luke, balloon hunting despite its danger was still something of a sporting event, not a killing field.

Luke, Dawson, and Lennon, each tried to claim credit for the balloon victory when they arrived back at the aerodrome. The squabble became just one more of those annoying disturbances Frank Luke would cause his new commander, Ack Grant. (Ultimately, each of the three men would receive credit for the victory.) After playing referee between his three pilots, Grant got an idea. Ignoring the one victory his squadron had scored that day, he threw a gauntlet before the swaggering blonde pilot that gave him so many headaches.

Pulling out a map, Grant drew a circle around the town of Buzy near the front lines of the ongoing offensive. “There’s a balloon there that has been giving us hell,” he said. “Corps has given our squadron the task of taking that balloon out. Luke, if you think you’re so damn good, go get that balloon. It is heavily protected, not only by Archie but by a whole flock of Fokkers. I’m going to send up a flight under Lieutenant Vasconcells. I want you to drop out of formation at Buzy and get that balloon. You can take one man with you.”

It was more than a challenge; it was a solution. Chances that Luke would succeed were slim at best, this job was a suicide mission at worst. If Luke failed, that might take some of the swaggers out of him. If he got killed in the process, well, no one but Wehner and Roberts would shed any tears.

The Drachen at Buzy was concern enough that Major Hartney himself came over from Group that afternoon to visit the 27th. Flight Leader Lieutenant Kenneth Clapp informed him, “Grant and I are going to send your boyfriend, Luke, on that assignment. Now, here’s the proposition: If he gets it, he stays on the 27th. If he fails and still comes back alive, you agree to transfer him to another outfit. Luke’s a menace to morale.”

Hartney didn’t say much, just nodded his head. Meanwhile, Frank Luke was preparing for his flight with the one other pilot he had been allowed to select to accompany him, Lieutenant Joe Wehner. The two men mapped out their mission in detail, like teamwork. Luke had loaded his guns with incendiary rounds, while Joe would arm with a mixture of tracers and slugs. Frank would fly in low to stitch a line of flaming rounds across the large black orb, while Wehner flew up high to pounce on any Fokkers diving on the balloon buster. It was a well-laid plan, but still fraught with danger.

At 2:30 in the afternoon, Vasconcells led his seven-planes as they lifted off from Rembercourt, followed by Luke and Wehner. As they neared Buzy, Frank banked his wings towards Joe, and then the two men broke away from formation to do their thing. This was the kind of stuff that had branded Luke an independent loner, only this time he was doing it under orders.

It was a stunningly clear afternoon, and even from a distance, Luke could see the Buzy Drachen hanging brazenly in the sky. In the distance near Waroq he noticed a second balloon. That would be his encore performance. High above him, Joe Wehner lurked, waiting for the dogfight that was sure to follow. Frank Luke knew Joe was going to have his hands full. In the distance, he counted eight enemy aircraft speeding in his direction to intercept his attack. Frank opened his engine wide, angling forward until he was rolling into a dive directly into a wall of exploding Archie and the looming shape of the German sausage. Gravity allowed his dive to reach speeds up to 160 mph, 30 miles per hour faster than the top speed of the Spad in normal flight. At such a dive, while holding fire until he was well within killing range, there was a very good chance he would take out the balloon in a collision instead of with bullets. Finally, at point-blank range, he opened fire with both machineguns. A stream of deadly fire ripping through the fabric…and then, his guns jammed…cooked by the rapid-fire of the incendiary rounds.

As his Spad passed the enemy balloon, he again felt the sudden rush of intense heat as gasses exploded and the balloon nearly disintegrated. As he passed the point of danger, his airplane began to shake under a horrible pounding to the side, as the bullets of an enemy Fokker raked him from prop to tail. The lead Fokker had nailed him and a second was coming in right behind him. Bullets splintered his instrument panel, shredded the canvas of his wings, and sailed furiously around his body in the exposed cockpit. Lieutenant Luke rolled to gain some distance, then tried to break for safety with the enemy on his tail. Both of his guns out of commission and his airplane damaged to the point of nearly falling from the skies, it would be up to his partner now.

Joe Wehner had seen the explosion and knew that his partner had accomplished what no other pilot expected him to do. Now he watched as Luke rolled toward the ground with enemy machinegun fire ripping his Spad to pieces. Despite the odds, the brave little kraut from Massachusetts tapped his own machine guns and headed out of the sun to surprise the Fokkers. The ferocity of his attack startled the enemy squadron, which quickly dispersed. By the time they realized that they were being assaulted by but a single American pilot, it was too late. Luke had disappeared, and Joe Wehner was hightailing it back to join Vasconcells and the other seven Spads for the flight back to Rembercourt.

“After the second patrol I had scarcely landed and made my way to Group headquarters when Grant, Clapp, and Dawson came galloping up, highly excited,” Hartney later wrote of that day. “Dawson was the spokesman:

“Listen Major, we want to take that all back. Boy, if anyone thinks that bird is yellow, he’s crazy. I’ll take back every doubt I ever had. The man’s not yellow; he’s crazy, stark mad. He went by me on that attack like a wild man. I thought he was diving right into the fabric. Then, even after it was a fire, I saw him take another swoop down on it. He was pouring fire on fire and a hydrogen one at that.”“Said Clapp, with tears in his eyes: ‘Gosh, Maj. Who spread that dribble around that Luke is a four-flusher? I’d like to kill the man that did. He’s gone, the poor kid, but he went in a blaze of glory. He had to go right down to the ground to get that…. balloon and they’ve got the hottest machine-gun nests in the world around it. They couldn’t miss him.”

The Arizona Boaster had lived, and died, up to his brag. Three balloons in three days. It was unheard of. In death, Frank Luke finally earned the respect of his fellow pilots, the admiration that had eluded him in life.

And then the field phone rang. It was the 27th Headquarters.

“Major, you’d better come down here quick and ground this bird, Luke. He’s ordered his plane filled up with gas. He just runs over to Wehner’s ship and he says they’re going out to attack that balloon at Waroq. His machine is full of holes, two longerons are completely riddled and the whole machine is so badly shot up it’s a wonder he flew her back at all. He’s crazy as a bedbug, that man.”

The Arizona cowboy was back in the saddle.

There was no third kill for Luke that afternoon. After an argument between Grant and Hartney ended with Grant posing the question to his Group Commander, “Who’s running this outfit (the 27th Aero Squadron) Major, you or me?” Hartney had backed off to leave the man who had replaced him at the helm of the Eagle Squadron to command in his own rigid way. A good senior commander doesn’t undercut those beneath him, and Hartney was a good senior commander.

That didn’t prevent him from telling Luke in private, “I appreciate all you’re doing. I’m so proud of you I hardly know what to do. It’s only a few hours since the army called for the destruction of those balloons and you did it. No outfit can beat that.”

Grant did allow Wehner to fly after the balloon at Waroq, but by the time Joe got there, it had been reduced to flames by French Ace Rene Fonck. It was probably just as well. Ack Grant temperament could probably have handled no more heroics from the two outcasts of the Eagle Squadron on this day. A dose of jealousy might have only added fuel to his previous hatred of Luke and his partner, and it was no consolation that Frank Luke was now the Group Commander’s fair-haired boy.

Things would only get worse for Grant on Sunday.

September 15, 1918

The three-day rampage of the balloon buster did indeed send ripples throughout the 1st Pursuit Group that reached all the way to the top of the Air Service Command. Colonel Billy Mitchell labeled the 27th his “balloon platoon”, and Luke had a friendly and open ear in Hartney to whom he could pitch his ideas. The Major was thinking about Luke’s ideas for twilight balloon hunts when his planes began taking off in the morning. Soon, another ripple of excitement spread through Group Headquarters; 94th Aero Squadron pilot Eddie Rickenbacker had just shot down his eighth confirmed airplane. The Hat in the Ring Squadron was now the home of America’s newest Ace of Aces.

Meanwhile, the balloon platoon was grudgingly preparing to carry out its own orders. Thanks to Luke’s success, the squadron had received orders that morning via courier assigning it the task of taking out three balloons at Tronville and the fourth balloon at Villers-sous-Paried. The squadron’s reputation, built by one daredevil pilot, seemed now to destine all of them to suicide missions.

Wehner was late taking off, so he was pushing his engine to catch up before Frank Luke broke away from the formation to do his work. Racing towards Etain (Boinville), Joe watched the mid-morning sky turn suddenly brilliant. Luke had beat him to the punch and nailed the first balloon on his own. Instead of flying towards the brilliant fire in the distance, Joe turned towards the second target he and Frank had marked that morning, the Drachen at Bois d’Hingry. Again, as he approached the area, the sky was filled with a bright orange flame and billowing white smoke. The Balloon Buster had struck again…two balloons and it wasn’t even lunchtime.

This time Joe continued towards the scene of the explosion, concerned that his partner might be under attack from enemy fighters. He arrived just in time to find Luke streaking for home, seven Fokkers on his tail. Wehner opened fire to give his friend breathing room, shooting down one (the kill was unconfirmed and never credited the soon-to-be Ace), and then both men raced for the American lines.

Frank had to land for repairs, but Wehner returned for a solo patrol to attack a balloon near Barq. After destroying it and shooting down one of its protecting Fokkers (neither victory was ever confirmed or officially credited), while returning he noticed eight enemy Fokkers attacking a single American observation plane. As he had defended Frank Luke against all odds, again Joe Wehner went into action, shooting down one and forcing the other to land out of control. For that action, he would ultimately be awarded his first Distinguished Service Cross, though he was officially credited with one kill…his first confirmed victory. (Wehner is also believed to have shot down one Fokker the previous day when he had covered Luke’s attack on the balloon at Buzy.)

Shortly before 5 that evening Luke and Wehner went out with yet another patrol in this busiest of days. As they neared the lines, the two pilots again split off from the main flight to hunt enemy balloons, but soon were separated. Northeast of Verdun Joe Wehner found his sausage hanging in the evening sky, and filled it with incendiary rounds, getting his second confirmed kill for the day…2 for Wehner (1 balloon and one Fokker) and 2 for Luke (both balloons). Yet the two flew once more on this day of days.

Luke was eager to test his ideas of hunting balloons in the earliest stages of advancing nightfall, and it was nearly eight o’clock when the skies lit up near Chaumont, and Frank Luke became a 6-kill Ace with three balloon victories in a single day. The feat was unprecedented, eventually earning Lieutenant Luke the Distinguished Flying Cross, though there would be no celebration back at Rembercourt. Attempting to return to his aerodrome, Luke became lost in the darkness and landed in a wheat field near Algers to spend the night, returning to the aerodrome afternoon the following day.

September 16, 1918

The St. Mihiel offensive ended its run with American soldiers pushing the Germans more than 10 miles backward in four days, the number of prisoners in the tens of thousands. Not only were the Kaiser’s ground forces in total disarray, but his airmen were also reeling from the loss of more than 100 planes and balloons in the period. The normally invincible balloon companies were especially shaken, nervous now at the site of two lone Spads in the sky. Luke and Wehner had become a legendary team among both friend and foe.

The newfound respect the enemy had for them was posing its own set of problems. The duo flew two separate hunting patrols on the afternoon of the 16th, but every time they neared a potential target, the German ground crews were winching the large Drachen to the ground well ahead of the hunters. It was frustrating for two men making aviation history, and Luke approached Major Hartney once again about flying dusk patrols. He and Joe had noted balloon positions as they were hauled safely into their nests at the approach of their Spads earlier, and now Frank was promising the Group commander a triple-punch victory in 20 minutes if only he would authorize the flight.

In the boisterous manner of speech that had made him the most despised man in the squadron, he pointed to a map and said, “Wehner can get one about 7:10, I’ll get another about 7:20, and between us, we ought to get the third about 7:30. Just start burning flares and shooting rockets here on the drome about that time (to light up the field) and we’ll get back all right.” This time, fellow pilots took Frank Luke and his big talk seriously.

Not only was the experiment approved, but it was also publicized and even closely watched by the commander of all the aerial forces, Colonel Billy Mitchell himself. Rickenbacker himself, his new title of Ace of Aces in jeopardy, watched the events unfold in admiration and fascination, later recording the evening’s activities in his autobiography, Fighting the Flying Circus. (Different accounts are written after the war detail events and actual times with some discrepancies, but the basic facts of the balloon attack of September 16 are generally accurate.)

“Just about dusk on September 16th Luke left the Major’s headquarters and walked over to his machine. As he came out of the door, he pointed out the two German observation balloons to the east of our field, both of which could be plainly seen with the naked eye. They were suspended in the sky about two miles back of the Boche lines and were perhaps four miles apart.

“Keep your eyes on these two balloons,” said Frank as he passed us. “You will see that first one there go up in flames exactly at 7:15 and the other will do likewise at 7:19.”

“We had little idea he would really get either of them, but we all gathered together out in the open as the time grew near and kept our eyes glued to the distant specks in the sky. Suddenly, Major Hartney exclaimed, ‘There goes the first one!’ It was true! A tremendous flare of flame lighted up the horizon. We all glanced at our watches. It was exactly on the dot!

“The intensity of our gaze towards the location of the second Hun balloon may be imagined. It had grown too dusk to distinguish the balloon itself, but we well knew the exact point in the horizon where it hung. Not a word was spoken as we alternately glanced at the second-hands of our watches and then at the eastern skyline. Almost upon the second our watching group yelled simultaneously. A small blaze first lit up the point at which we were gazing. Almost instantaneously another gigantic burst of flames announced to us that the second balloon had been destroyed. It was a most spectacular exhibition.”

It had indeed gone like clockwork; Luke and Wehner both attacking the first balloon over Reville (for which each would get credit). Even as the flames from that first victory were fading into the darkness, Luke was single-handedly dropping the second balloon at Romagne in burning refuse over its ground crew, while they, in turn, filled the sky with deadly bursts of Archie and machinegun fire. Minutes later Joe Wehner was completing the triple-play as he flamed the Drachen at Mangiennes.

As the third balloon exploded, the ground crews at Rembercourt lit the sky to mark the field for their returning heroes, a fireworks display befitting the encore performance of the St. Mihiel offensive. For Joe Wehner, it was four confirmed victories in two days. For Frank Luke, it was an incredible eight balloons in five days…and the new title American Ace of Aces. Eddie Rickenbacker said he didn’t mind being supplanted by the action, “We all predicted that Frank Luke would be the greatest air-fighter in the world if he would only learn to save himself unwise risks.”

Madman from Arizona

In the myriad of stories that were told and written about the Great Balloon Buster after the war, Frank Luke is often referred to as a “Madman” for the fearless abandon with which he attacked the Germans. On that night in September, as well as in the battles of the previous day, Lieutenant Frank Luke was far from MAD. Independent, yes. A loner, to some degree, though his friendship with Joe Wehner shows he understood teamwork to some degree. But Frank Luke did not wage warfare with crazy abandon, however. His incredible string of victories was the result of skillful flying, careful planning, and cunning calculation. All of that changed two nights after the famed triple-play.

America’s new Ace of Aces was a phenomenon, worshipped by the infantrymen who witnessed his amazing displays over enemy lines, revered by the mechanics who patched up his Spad after each action while marveling at his survival and envied by pilots of both the Allied and German air forces. If Luke had any competition for first place in the ace category, it would come from Joe Wehner, not Eddie Rickenbacker or one of the other great fliers of the day.

Indeed, after the night of September 16 when Frank Luke bagged his eighth balloon, Joe Wehner could only claim four victories. In fact, had they all been confirmed and counted, Joe might have been one victory ahead of Frank. But where Frank and Joe were concerned, there wasn’t a competition but a sense of teamwork. Rickenbacker described them thus:

“There was a curious friendship between Luke and Wehner. Luke was an excitable, high-strung boy, and his impetuous courage was always getting him into trouble. He was extremely daring and perfectly blind and indifferent to the enormous risks he ran.

“Wehner’s nature, on the other hand, was quite different. He had just one passion, and that was his love for Luke. He followed him around the aerodrome constantly. When Luke went up, Wehner usually managed to go along with him. On these trips Wehner acted as an escort or guard, despite Luke’s objections. On several occasions he had saved Luke’s life. Luke would come back to the aerodrome and excitedly tell everyone about it, but no word would Wehner say on the subject.

“Wehner hovered in the air above Luke while the latter went in or the balloon. If hostile aero planes came up, Wehner intercepted them and warded off the attack until Luke had finished his operations. These two pilots made an admirable pair for this work and over a score of victories were chalked up for 27 Squadron through the activities of this team.”

To say that Frank Luke was a loner who didn’t need anybody on the night he became America’s Ace of Aces would be to ignore one of military history’s legendary friendships. The day following their spectacular night show, the two men went souvenir hunting together in the trenches and villages near the front lines. For the 27th, as well as most of the other squadrons, the successful conclusion of the St. Mihiel offensive warranted a day off.

To say that Frank Luke was a loner who didn’t need anybody on the night he became America’s Ace of Aces would be to ignore one of military history’s legendary friendships. The day following their spectacular night show, the two men went souvenir hunting together in the trenches and villages near the front lines. For the 27th, as well as most of the other squadrons, the successful conclusion of the St. Mihiel offensive warranted a day off.

Frank had always wanted to capture an enemy airplane with machineguns intact to send home as mementos of his service in France. As the two scoured the battle-torn countryside, they located a bombed-out-house containing the bodies of a dozen Germans and two machineguns. Like kids, Luke and Wehner loaded the guns in their car to return to Rembercourt. There they cleaned and polished their trophies and shipped them to Paris to be held for them.

Shortly after 5 o’clock on the evening of Wednesday the 18th, the American infantrymen in the trenches heard the sound of two airplane engines. Looking skyward, they noticed two lone Spads crossing the lines and heading into enemy territory. The tempo seemed to pick up on the ground, and all eyes strained towards the east in anticipation of what they all knew was coming. High above Luke and Wehner could not hear the excited shouts of encouragement or see the waves of the weary soldiers. Instead, their attention was focused on Three Fingers Lake, the largest body of water in the area and a position the Germans had fiercely held since the earliest days of the war. With the doughboys driving them ever backward, the Boche had hoisted two important balloons, carefully placed near the lake where they could easily observe the American troop movements and report back to the military planners on the ground.

While Wehner remained hidden high above, Luke went into a dive on a balloon tethered above a swampy area at the northwest edge of the lake. Echoes of heavy anti-aircraft fire rolled across the countryside as Luke pointed his Spad at the first target, never wavering as deadly missiles swarmed around him. At the last minute, before it would seem his plane would disappear into the side of the Drachen, Luke opened fire and banked away for a second pass, then a third. Rickenbacker wrote, “Three separate times he dived and fired, dived and fired…constantly surrounded with a hail of bullets and shrapnel, flaming onions and incendiary bullets.” Suddenly the eruption of the volatile gasses mushroomed into the heavens and Lieutenant Luke banked, leveled off, and pointed his Spad east towards the second target.

To the west Luke noted six German Fokkers rushing to cut him off, but chose to withdraw by way of the second balloon in hopes of destroying it with a casual burst as he passed. Flying east towards his target, the six Fokkers managed to flank Luke to the south as he boldly dove at the second Drachen as the ground crew frantically tried to winch it down. Luke’s success could not be missed…the lights of the exploding German sausage being witnessed all the way back to the American trenches. And then the six Fokkers were on him, supplemented by three more that had slipped in from the north to catch him in a classic crossfire.

Whether by crafty design or by simple opportunity, the German fighter pilots had drawn the two American Aces into a well-laid trap. When Wehner dove to the rescue of his partner, he failed to see the three Fokkers that broadsided him from the north. In a moment the thrill of victory turned to horror as Luke watched his partner’s Spad rollover, and then begin to fall, flames issuing from its fuel tank. And then, suddenly, Lieutenant Frank Luke did become a madman.

At the moment the intrepid Frank Luke should have finally said “enough” and broke for home, a rage built up inside of him at the loss of his one friend. Banking his Spad, he hurled himself with abandon at the three Fokkers, both guns filling the heavens with deadly missiles of death.

Diving on the enemy plane to the left, Luke fired until it burst into flames and dropped from the sky. The other two enemy fighters were on his tail and zipped past with their own machine guns blazing. Luke ignored the hail of death, banked, and dove in on the second enemy Fokker. In his rage, the fusillade was both intense and accurate. In the space of ten seconds, the Balloon Buster had destroyed two enemy fighters and sent the third running for home. His wrath still unabated, Luke banked again to seek out the remaining six Fokkers. They too were gone, fading into the east.

Diving on the enemy plane to the left, Luke fired until it burst into flames and dropped from the sky. The other two enemy fighters were on his tail and zipped past with their own machine guns blazing. Luke ignored the hail of death, banked, and dove in on the second enemy Fokker. In his rage, the fusillade was both intense and accurate. In the space of ten seconds, the Balloon Buster had destroyed two enemy fighters and sent the third running for home. His wrath still unabated, Luke banked again to seek out the remaining six Fokkers. They too were gone, fading into the east.

In frustration, Luke scanned the horizon. North of Verdun he could see the allied anti-aircraft fire in the twilight, indicating there was a German plane somewhere over the Allied sector. Luke banked and headed for the action, heedless of six more Fokkers that dashed to the rescue of their low-flying Halberstadt. The two-seater was an observation plane, taking photos of the American positions at low altitude.

Luke zoomed past five French Spads, leaving them to deal with the Fokkers, as he dove on the German observation plane, both guns firing incessantly. The large enemy airplane shivered against the pounding, then nosed over and plummeted to the ground. Luke was out of fuel and quickly switched to his 10-minute reserve tank, coasting into the forward advance field at Verdun. The field itself was under the command of Jerry Vasconcells, and it was there Luke spent his first tortured night after the loss of Joe Wehner. The victory was hollow in the face of his great loss, and Frank Luke would never be the same again.

That night General John J. Pershing receives a telegraph that read: “Second Lieutenant Frank Luke, Jr., Twenty-seventh Aero Squadron, First Pursuit Group, five confirmed victories, two combat planes, two observation balloons, and one observation plane in less than ten minutes.” It was an accomplishment almost unprecedented in the history of aerial combat.

Thursday morning Major Hartney himself drove out to pick up Lieutenant Luke and bring him home. Knowing well the young man would be fighting the weight of emotion brought on by the loss of his friend, Hartney asked the stable and reliable Eddie Rickenbacker to join him. (Hartney also took along the Group’s YMCA girl, Mrs. Welton).

They found Luke in a morose state, unsatisfied with his incredible record of combat. His first question was, “Has Wehner come back?” Rickenbacker and Hartney just looked at each other in silence. Frank Luke had known the answer, even before he’d asked the question. Still hoping against hope, the two men who had lost friends of their own, personally drove Frank to military headquarters in Verdun to see if any word of Wehner’s fate had been uncovered. There was no word of the missing Ace, now credited with six kills (some records list him with only five, omitting the very plane he received the DSC for destroying on September 15th.) For his part in the September 16th triple-play that had been witnessed by so many, Wehner did receive a second posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

While at Verdun HQ, Luke was informed that not only had his previous night’s five kills been confirmed, but that three earlier victories had also been confirmed. The man from Arizona was credited with knocking down 14 enemy balloons and airplanes in only eight days. “The history of war aviation, I believe, has not a similar record,” wrote Rickenbacker in Fighting the Flying Circus. “Not even the famous Guynemer, Fonck, Ball, Bishop, or the noted German Ace of Aces, Baron von Richthofen, ever won fourteen victories in a single fortnight at the front.

“In my estimation there has never during the four years of war been an aviator at the front who possessed the confidence, ability and courage that Frank Luke had shown during that remarkable two weeks.”

That night the entire 1st Pursuit Group held a dinner in honor of Frank Luke, now a reluctant hero. When Major Hartney introduced him and asked the young lieutenant to say a few words, Luke stood quickly to his feet and simply quoted the father of one of the squadron’s fallen comrades, “I’m having a bully time.” Then he sat down amid a round of laughter, forcing a smile he really didn’t feel in his heart. Frank Luke was a changed man.

Somewhere in the two days following his fourteenth victory and Joe Wehner’s death, the Army sent a photographer to Rembercourt. The pictures probably comprise the best recollection the world would have of the Balloon Buster and the most accurate look into his soul. Traveling into the countryside near Verdun, the wreckage of the Halberstadt that had been Luke’s last victory was located. It was the only of Frank’s victims to ever fall inside friendly lines. There, Frank Luke posed for what is perhaps his most famous photograph. A closer look at his face reveals not the smile of a victorious hero, but the haunting gaze of a tortured soul.

Somewhere in the two days following his fourteenth victory and Joe Wehner’s death, the Army sent a photographer to Rembercourt. The pictures probably comprise the best recollection the world would have of the Balloon Buster and the most accurate look into his soul. Traveling into the countryside near Verdun, the wreckage of the Halberstadt that had been Luke’s last victory was located. It was the only of Frank’s victims to ever fall inside friendly lines. There, Frank Luke posed for what is perhaps his most famous photograph. A closer look at his face reveals not the smile of a victorious hero, but the haunting gaze of a tortured soul.

Conspicuous by its absence in any of the written records by Hartney, Rickenbacker, and others are the reaction of Luke’s commander Alfred “Ack” Grant. It is safe to assume that Grant never overcame his personal dislike for Frank Luke, and resented, even more, the successes that endeared him to Colonel Mitchell and Major Hartney. The brewing clash of personalities would resurface again.

For the moment, Major Hartney could see that Frank Luke was near the breaking point. At the dinner in Ace’s honor, Hartney presented Frank with the most coveted prize in the Group – a seven-day pass to Paris. While Luke languished alone with his thoughts in the French capital, the entire world was learning of his exploits. Headlines in the September 21 New York Times read:

11 GERMAN BALLOONS

HIS BAG IN 4 DAYS

“The Last Straw”

Not even the magic of Paris could soothe the tortured soul of Lieutenant Frank Luke, and he returned from his leave early, probably much to the consternation of Lieutenant Grant. Ack had been at a loss as to how to deal with Luke for weeks. He was convinced the Arizona Balloon Buster had no respect for authority, no regard for orders, and was bent on becoming a one-man show in the air. At least with Luke in Paris for a week, the problem had a temporary solution. Luke’s early return was not entirely a welcomed one.

While Luke had been gone, the ever-steady Vasconcells moved his B-Flight to the advance field at Verdun. On September 26, the day after B-Flight’s arrival, the Allied forces opened their Marne offensive. It was to be a push to drive the Germans out of the Argonne Forest, and ultimately lead to the end of the war within six short weeks. Eddie Rickenbacker had done his part by knocking down three planes the previous day, the same day he also became commander of the famed Hat in the Ring Squadron. Despite his impressive record for the day, Frank Luke’s position as Ace of Aces was intact, and Rickenbacker’s intent according to his own autobiography had not been to compete with the Eagle Squadron’s leading pilot, so much as to compete with the entire squadron. Prior to that date, thanks to Frank Luke, the 27th Pursuit Squadron was the top squadron in the 1st PG by six victories. Almost since the inception of 1st Pursuit Group, under the leadership of the great Raoul Lufbery, the 94th had always led the pack. Rickenbacker was determined to see his squadron reclaim their position.

Frank Luke was back for the opening day of the offensive, flying out with Lieutenant Ivan Roberts, one of his few friends from the early days before the Arizona Boaster had been transformed into America’s greatest hero of the air. It was Luke’s first combat mission since the death of Joe Wehner seven days earlier.

While looking for balloons, Luke spotted a formation of five Fokkers near Consenvoye and Sivry and attacked. Though he claimed one victory and flamed a second, neither was ever officially credited to his already impressive tally. Ivan Roberts never returned from the mission. The last time Luke had seen his new wingman, Roberts had been tangling with two Fokkers on his own. The loss of two wingmen, both counted among his few friends, in two consecutive combat missions, was the final straw in the fragile psyche of Frank Luke. Never again would he fly in formation with, or endanger the life of, another American pilot. In Frank’s own mind, though he might be the greatest curse on enemy aircraft along the Western Front, he was a jinx to any Allied pilot who flew with him.

Returning to Rembercourt Frank thought about his new policy to only fly solo from that point on, fully aware that his vow would in all probability result in the loss of his wings or perhaps even courts-martial at the hands of his by-the-book squadron commander. Bypassing the chain of command, Luke went directly to Major Hartney, requesting permission to transfer to Vasconcells’ field near Verdun, where he would operate independently…and alone. Hartney agreed to discuss the matter with Grant, and Luke returned to his squadron to await the decision.