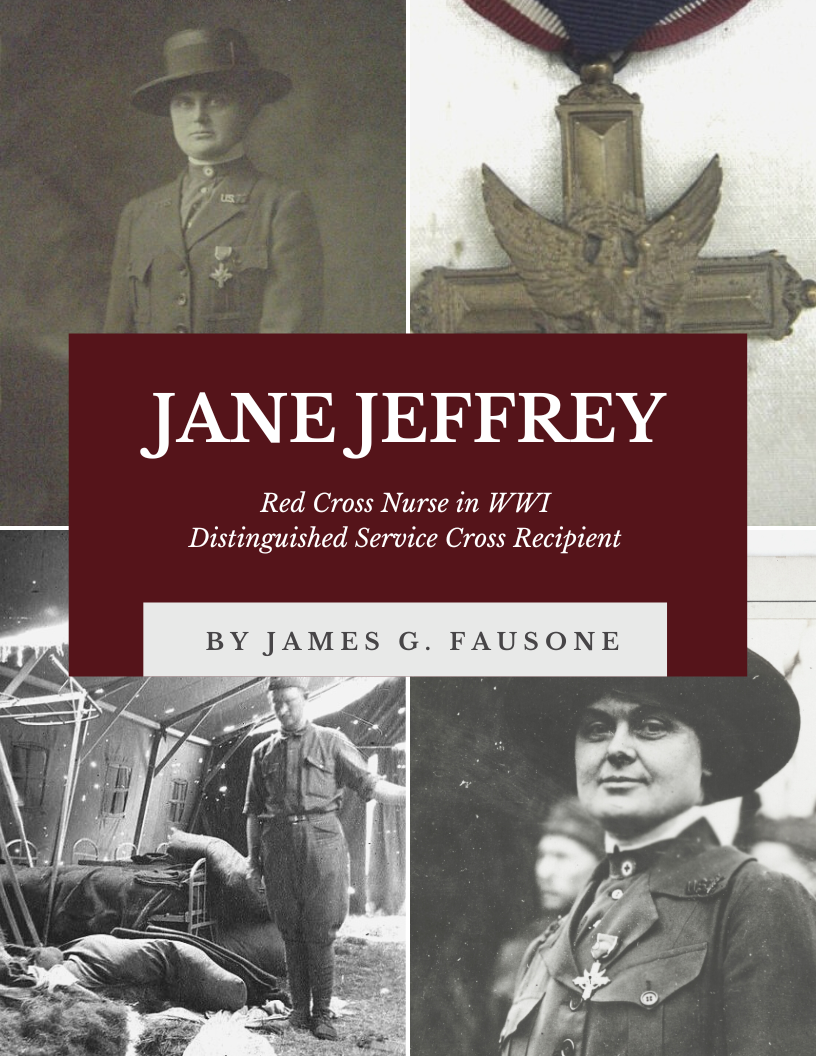

Jane Jeffrey

Jane Jeffrey

WWI Nurse & DSC Recipient

By: James G. Fausone

Jane Jeffrey was a Red Cross nurse during World War I. She followed in the footsteps of giants in the profession and proved again that women in war are patriotic and do their duty in the face of danger. To understand Jane, one must understand the context of her life in nursing, women’s progress, and world conflict.

English Roots & 1900’s Nursing

Jane Jeffrey was born on September 28, 1881, in Newmarket, England. Newmarket is a market town in the English country of Suffolk, approximately 65 miles north of London. It is generally considered to be the birthplace and global center of thoroughbred horse racing. This region dates back to the early 1200s. English royalty has been visiting the area since the 1600s as thoroughbred horse racing became known as the “Sport of Kings.” Even today, Queen Elizabeth II visits the region for its thoroughbreds and racing.

Nursing was not always the most trusted profession it is today. In the United States for over two decades, according to a Gallup Honesty and Ethics poll, it is the most trusted profession. (The only year it was not rated first was 2001 when firefighters received that honor post-9/11). Everyone seems to have a favorite nursing story. Maybe it was a school nurse, a doctor’s office nurse, or one working in the hospital that demonstrated compassion, empathy, care, and concern. Those collective actions make nursing the top-rated profession for 81% of the population. However, respect for the profession only began in the 1900s. At that time, it was an all-female profession, low-paid, and building on the nurturing disposition of women.

The most famous nurse of the century was Florence Nightingale, an Italian who grew up in England. In 1844, Florence decided to work at a hospital but her parents were opposed to this idea. In England in the middle of the nineteenth century, nursing was not a decent job. In July 1850, she went to Germany and France to work as a volunteer in hospitals. Then in 1853, she returned to London and worked as a manager in the “Institue for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen.”

In 1854, Britain, France, and Turkey were all at war with Russia, another Crimean war. The Russians were defeated but England suffered many casualties. There was a lack of medical facilities and high mortality in British military camps. Sydney Herbert, the minister of war, was a friend of Nightingale; so, she offered her services. Nightingale, with 38 nurses, went to a military camp of British soldiers located on the outskirts of Constantinople (Istanbul). She observed the unsanitary conditions in the camps drawing a conclusion: in every thousand injured soldiers, six hundred were dying because of communicable and infectious diseases.

Nightingale’s interventions were simple. She tried to provide a clean environment. She provided medical equipment, clean water, and fruits. With this work, the mortality rate decreased from 60% to 42%, then to just 2.2%.

Her nursing attracted the attention and support of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and Prime Minister Lord Palmerston. Florence asked them for permission to conduct an official investigation into the context of the military hospitals. The request was granted and the Royal Institute of Research on the Health of the Military was established. Jane Jeffrey was a humanitarian, medical scientist, and statistician.

Nursing in the United States was critical to military campaigns since the Revolutionary War but was not recognized. Prior to the Civil War, nursing had not yet established itself. The Civil War changed all that once it began in 1861. It provided women with a specific opportunity to contribute. The Battle of the North and South influenced the development of healthcare; as a result, increased health needs during the war, and many new institutions and organizations were formed during this period. When the war ended in 1865, there had been 600,000 casualties with approximately 10 million cases of illnesses, significantly higher than any other American war.

During the 1898 Spanish-American War, the Army hired female civilian nurses to help with the wounded. Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee was the Acting Assistant Surgeon in the U.S. Army at the time. After the war ended, McGee pursued the establishment of a permanent nurse corps. She is now known as the founder of the Army Nurse Corps. In all, more than 1,500 women worked as contract nurses during this conflict.

As the country and its conflicts moved through the late 1800s it became obvious a more formal structure was necessary to adequate nursing care for soldiers. The U.S. Army Nursing Corps was established in 1901, with just barely enough time to establish and populate the fledgling corps by the start of the Great War in 1914.

Significant developments in nursing, and its intersection with military conflicts, were rapidly progressing in the 1850-1917 period. Jane Jeffrey would have been drawn into this new and exciting profession that was necessary in times of peace and war. Little did she know that by coming to the United States in 1908, her vocation was going to be called upon again to serve in the military.

World War

Never before had war spread across the entire continent of Europe, let alone dragged other non-European countries into the fold. The Great War was beyond comprehension and certainly was not considered by the military and medical planners. War creates disruption and opportunity. Many women seized the opportunities created by war and advanced the cause of women and nursing.

Madame Marie Curie took her radiation experiments and created a mobile x-ray machine to be used in the field. Curie invented the first “radiological car” – a vehicle containing X-ray and photographic darkroom equipment – which could be driven right up to the battlefield where army surgeons could use X-rays to guide their surgeries. She recruited 20 women for the first training course, which she taught along with her daughter Irene, a future Nobel Prize winner herself. She also recruited women as drivers and mechanics for the fleet.

The Great War created a great nursing expansion. Women were encouraged to answer the call for nurses at home and abroad. The U.S. Army and American Red Cross were calling out for help. Jane heard that call and happily answered it to help in the Great War effort.

Following in Nursing Footsteps to War

Little is known of Jane Jeffrey’s birth, family, upbringing, or early education in Newmarket, England. Her initial voyage to America is not recorded. Records exist of a trip she took from England to the United States to nurse a family member in Massachusetts.

From Red Cross archives, here is what we know about Jane Jeffrey’s work experience:

- Graduated from Taunton State Hospital School of Nursing, Taunton, Massachusetts – 1905

- Received extra training at Providence Lying-In Hospital, Rhode Island – 1906

- General Memorial Hospital, New York City – 1909

- Head nurse for 6 years at Channing Sanitarium, Brookline, Massachusetts

- Nine months in private duty nursing

For some of this time, she was also caring for her aunt, Mrs. James Baldwin of 36 Bellevue Meeting House Hill, Dorchester, Massachusetts. Jane was a registered nurse in good standing in the Massachusetts State Nurses Association.

She returned to England for a visit home. Then in September 1908, sailed on the RMS Etruria from Liverpool, England to New York. Etruria was a ship of the Cunard line. The ship epitomized the luxuries of Victorian style. The public rooms in First Class were full of ornately carved furniture and heavy velvet curtains hung in all the rooms, and they were cluttered with bric-a-brac that period fashion dictated. By the standard of the day, the Second Class accommodation was moderate but spacious and comfortable. The ship’s manifest lists Jeffrey’s age as 28 and her occupation as nursing. No other Jeffrey was traveling with her on that voyage.

From afar, Jane Jeffrey watched as her homeland became embroiled in war in 1914. She was unmarried and likely underpaid as a nurse. At 37 years old, she was poised to help when America declared war in April 1917.

American Red Cross in the Great War

The Great War also created a period of extraordinary growth for the American Red Cross. Unexpectedly, the war also helped spread the Spanish Flu. The war and this flu required the services of the American Red Cross and all the nurses and doctors it could provide. The Spanish Flu claimed 22 million lives worldwide and an estimated 500,000 in the United States. The Red Cross’s war efforts involved establishing approximately 50 hospitals overseas, mostly in France.

Already established as an important branch of the Red Cross before the war, the Nursing Service greatly expanded with the coming hostilities. Its principal task was to provide trained nurses for the U.S. Army and Navy. The Service enrolled 23,822 Red Cross nurses during the war. Of these, 19,931 were assigned to active duty with the Army, Navy, U.S. Publish Health Service, and the Red Cross overseas. The Red Cross also enrolled and trained nurses’ aides to help make up for the shortage of nurses on the home front due to the war effort.

In an American Journal of Nursing article in November 1917, Jeffrey was included with a group to help in the war effort organized by Elizabeth Sullivan of Children’s Hospital, Boston. This group was assigned to the American Red Cross Children’s Bureau.

Within weeks of the American declaration of war, the Red Cross sent “The Mercy Ship” with 170 doctors and nurses to Europe to assist with combat casualties on both sides of the war. The Geneva Conventions required strict observance of neutrality and impartiality by the Red Cross medical personnel.

This duty with the Red Cross was not without risk. There were reported to be 330 female Red Cross war casualties – assuming all are nurses – it was 1.5% of all nurses working for the Red Cross. Also, the Red Cross noted that “the casualty rate among American nurses in military service” was high principally from disease.

Jeffrey was sent to Bordeaux, France, where she served before being transferred to a military hospital in Jouy-sur-Marne. Jouy is east of Paris about 50 miles along the Grand Morin River. She was assigned to ARC Hospital #107. It had previously been a French-staffed military hospital. She found difficult conditions, including tents that housed the hospital wards and no plumbing. Wounded soldiers arrived in large numbers, straining the ability of doctors and nurses to treat them.

Just nine months after joining the American Red Cross her hospital was bombed. On July 15, 1918, the hospital at Jouy was attacked by German aviators. Two hospital orderlies were killed, and 14 persons were injured, of whom nine were orderlies, four patients and one American Red Cross nurse. Jeffrey is the one ARC nurse.

No possible doubts exist as to the deliberate character of the raid as the hospital was marked by an immense white canvas cross on the lawn. The signage had been proven by photographs taken from an airplane, to be distinctly visible several thousand feet in the air. Seven witnesses agree that the German pilots were down to within several hundred feet to make observations before dropping their bombs. Shrapnel is indiscriminate, not adhering to the Geneva Convention protocols.

American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress)

The Stars and Stripes byline: “France, Friday, July 19, 1918” reported “Two Hun Planes Drop Bombs on A.R.C. Hospital… Four Wounded Men Hit… One is Struck in Spot from Which Piece of Shrapnel Had Just Been Removed.” The newspaper report found that bombs were dropped and two fell squarely on the roofs of the hospital tents. Furthermore, there were no military buildings nearby and the railroad tracks were three kilometers distant. The article goes on to report:

“Miss Jane Jeffrey, the only Red Cross nurse who was wounded, was struck near the spine by a piece of metal which traversed the entire length of a ward only a few inches above a long row of mostly surgical cases and penetrated the end wall of the tent outside of which she was standing.”

(Courtesy: valor.militarytimes.com)

Stars and Stripes further reported the irony of the attack as the hospital, until recently, 60-wounded German prisoners who received exactly the same treatment accorded to other patients.

During and immediately following the attack, Nurse Jeffrey, being true to her profession, continued to administer aid to those in the hospital and just wounded. Her extraordinary efforts did not go unnoticed. She was awarded the Legion of Honor, which is France’s premier order for military and civil service. The Legion of Honor was created by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802 to recognize extraordinary service.

This unprovoked and deliberate attack would have ended Jane Jeffrey’s nursing efforts during the war. She was hospitalized in Paris for a few months before heading back to the United States.

When she came back to the United States, she was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) for her work. The DSC citation reads:

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Nurse Jane Jeffrey, a United States Civilian, for extraordinary heroism while she was on duty at American Red Cross Hospital No. 107, at Jouy-sur-Morin (Seine-et-Marne), France, 15 July 1918. Miss Jeffrey was severely wounded by an exploding bomb during an air raid. She showed utter disregard for her own safety by refusing to leave her post, though suffering great pain from her wounds. Her courageous attitude and devotion to the task of helping others was inspiring to all of her associates.”

American Red Cross Nursing History

The “History of American Red Cross Nursing” reports on “The European War” and the attack on Jouy-sur-Morin this way:

“At Jouy-sur-Morin, on the night of July 15, Jane Jeffrey, an American Red Cross nurse transferred from the Children’s Bureau, was severely wounded. A French dispatch contained the following comment:

Located in a quiet, remote spot, three kilometers from the railroad, the hospital at Jouy-sur-Morin not only bears the distinctive marks of the sanitary service but on a nearby grass plot there has been spread a huge cross made of white towels, its arms measuring thirty meters. Shortly after the inauguration of the hospital, one of the Allied planes flew over the spot taking photographs to show that the cross was plainly visible from a height of many thousand meters. Shortly after the inauguration of the hospital, one of the Allied planes flew over the spot taking photographs to show that the cross was plainly visible from a height of many thousand meters.

During the night of July 15, two German aviators flew above the American hospital; volplaning, they descended to within a few hundred meters of the buildings and dropped four bombs. It was midnight.

In the operating room, the surgeons were at work. At the moment the first bomb struck, Major McCoy held in his forceps the femoral artery of the patient he was operating on. The lights went out, and two more bombs fell, the third failing to explode. In one room, an orderly was killed as he was giving a drink of water to a patient Nine were wounded… one of whom was an American Red Cross nurse.

We remember that recently sixty German prisoners were treated in this hospital at Jouy-sur-Morin, where they received from perhaps the very nurse whom they have wounded the same care and attention which she was giving our soldiers.

Miss Jeffrey was on night duty attending her patients when a fragment of shell struck her. She showed great spirit and was only concerned because she felt she was causing more trouble to the already overworked staff of doctors and nurses. When I told her the next day we were going to bring her into a hospital here in Paris, she was greatly disappointed. She had hoped to be able to go on duty again in a few days.”

(Maine H.S.)

Post-War Life of a DSC Nurse

After the war, she had a period of poor health after her experiences in France. Jeffrey joined the U.S. Public Health Service in New York City but had to resign for health reasons. She had back pain and stress-related issues among other problems. Her records are quite different from newspaper accounts.

The American Red Cross Historical Program and Collection shared a handwritten note from Jeffrey dated April 1921 talking about the effect of her war injuries and wondering about compensation:

“I am writing to ask you if the American Red Cross made any provision for the Red Cross nurses who were disabled or physically injured during the late war.

I was wounded at Jouy-su-Morin on July 15, 1918, while on night duty during an air raid. Unfortunately, while I was working under the direction of the Red Cross instead of the U.S. Government. Otherwise, I would have received compensation or provision made for vocational training as I am incapacitated from continuing my profession.

You may have heard that the U.S. Government conferred the honor of the D.S.C. upon me, which, as you know carries no remuneration & in no way compensates me for my inability to earn my living.

After my return to America & my discharge from the Red Cross which took place immediately after my arrival & without any physical examination, I took treatments for one year for my back at my own expense. In the meantime, I tried to do various work because it required less physical exertion but had to give it up.

For the past six months, I have been doing dental clinic work in a U.S.P.H.S. Hospital, but feel I must give it up.”

While still recovering, Jeffrey was offered a job as a nurse at the Poland Spring House in Poland, Maine, by its proprietor, E.P. Ricker. This offer was 135 miles away from Dorchester and in the Maine countryside. Poland Springs was 37 miles north of Portland, Maine, surrounded by hills and lakes. Jeffrey was unmarried, without children, and after experiencing war, she was in need of some peace, pay, and tranquility.

Long before Poland Springs was a national bottled water brand, it was a local inn. The Ricker family started building the inn around 1797, and it was a major force in Maine for generations. Over the next 100+ years, the inn was expanded and became a rest. Management of the operations passed from one Ricker generation to another. An inn pamphlet explained the history: “By 1875… Alvan Bolster Ricker, the second son, was taken into the firm, and the same year the Poland Spring House was commenced and opened in 1876. The kitchen was under Alvan Bolter Ricker’s supervision. The perfectly vented department was larger and more convenient than many major hotels. Guests were welcome to watch the food preparation and serving. A.B., as he was called, passed on all food and the dealers in New York and Boston kept the very best for the Rickers.”

Family history reports: “Poland Spring… was in need of a year-round nurse and… persuaded Miss [Jane] Jeffrey’s to accept the job and it was there that she met Alvan Bolster Ricker… whose wife, Cora Saunders Ricker, had passed away. She married Mr. Ricker on September 3, 1925.”

The celebrity age of Poland Spring’s history did not come until the twentieth century. Presidents William Howard Taft, Calvin Coolidge, and Warren Harding also visited the rest. Joseph Kennedy liked to bring his young family of aspiring politicians. Also relaxing at the resort were sports celebrities like Gene Tunney, Babe Ruth, and Sonny Liston, and entertainers like John Barrymore, Joan Crawford, Jimmy Durante, and Robert Goulet.

The American Art PostCard Company

(Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Poland Springs became famous for its water, not its Distinguished Service Cross resident. Water had bubbled up to the surface long before the Rickers arrived on the scene. Several stories circulated about miraculous cures, including one in 1844 that the water had healed Hiram’s upset stomach, which eventually took hold as the origin of the water business. Water did not become an active and viable commercial enterprise until 1860, however. That is when Hiram Ricker began advertising the water for sale and encouraging doctors to prescribe it medicinally.

In 1859, Hiram Ricker started packaging and selling Maine’s spring water. In 1980, Perrier bought Poland Spring, and then in 1992, Nestle North America bought Perrier.

Jane was 45 when she married Alvan Bolster Ricker, who was 65. She had married late in life into a privileged Maine family. This was a long way from Newcastle, England. A.B. Ricker passed away in 1933 at 83 years old. The couple had been married for 18 years.

Jane herself lived to the age of 79, passing away in 1960. Jeffrey was an unlikely Distinguished Service Cross recipient and an unexpected heiress. She honored her husband upon her death bequeathing funds to establish the library in Poland Spring.

The construction allotment was $60,000 plus funds in trust for its perpetual operation and maintenance. The library was to be called “The Alvan Bolster Ricker Memorial Library and Community House” in memory of Alvan B. Ricker, husband of Jane and the grandson of Wentworth Ricker, who constructed the Mansion House in 1797 to start the famed Poland Spring resort.

Jane Jeffrey Ricker was posthumously awarded a citation by the Editors of Who’s Who in America on March 30, 1966. The citation was awarded to Mrs. Ricker “as the donor of the most substantial gift in relation to the total annual income of an American library.”

She was undoubtedly thinking of the well-being of generations to come when making her bequest, just as you would expect from a nurse. Jane Jeffrey lived a full and unexpected life. The compassion and empathy of a nurse coursed through her veins her entire life.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment that you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Heroes Stories Index

All Major Military Award Recipients (PDF)

Our Sponsors