Leon "Bob" Vance

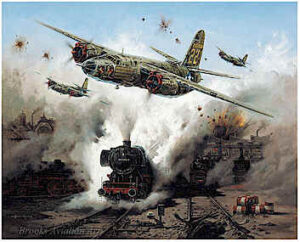

Crash Landing in the Channel

Lieutenant Colonel Leon Vance bit his lip and grimaced against the lingering pain as he recovered in an Air Force Hospital in England. During his better moments, he reflected on all that had happened, the mission that had almost killed him as well as the amazing series of unbelievable happenstances that had spared his life. Back home his beautiful wife and young daughter had learned that he had been wounded and anxiously awaited his return. In his mind, he could picture them, eagerly waiting for his homebound flight to return, then rushing towards him as he walked down...

Lieutenant Colonel Leon Vance bit his lip and grimaced against the lingering pain as he recovered in an Air Force Hospital in England. During his better moments, he reflected on all that had happened, the mission that had almost killed him as well as the amazing series of unbelievable happenstances that had spared his life. Back home his beautiful wife and young daughter had learned that he had been wounded and anxiously awaited his return. In his mind, he could picture them, eagerly waiting for his homebound flight to return, then rushing towards him as he walked down...

Then the difficult moments of his convalescence would creep in as reality forced itself upon his tortured mind. Bob Vance would not be walking anywhere; his right foot was gone--severed on his second combat mission. With the loss of that foot, Vance realized, a budding and bright military career had also vanished.

Throughout the month of June 1944, the most important news of the war flooded the airwaves, newspapers, and casual conversations. One day after Vance's second, and final air mission, Allied forces had stormed ashore at Normandy. It was the fulfillment of three years of planning, training, and intensive air warfare. Lieutenant Colonel Vance, the man who had trained so many young airmen to make this day possible amid promises that he would not only join them in combat but earn the Medal of Honor, was confined to a hospital.

Initially, Vance had tried to deal with his loss through an exaggerated sense of humor, asking the doctors to not only preserve his severed foot but to have it mounted for him. "It was sort of crazy, I suppose," he recalled, "but I really wanted the damned thing." On other days he found himself, quite naturally, fighting intense feelings of self-pity. And then, while struggling through all these emotions, he received news from the States that his father had died. Despite the fact that Bob Vance was alive, only because of what most people might consider an unbelievable series of small miracles, it was nearly impossible to see any positive side of life.

As the weeks passed, Vance began to move about more, hobbling from place to place inside the hospital on a pair of crutches. Eventually, he ventured outside, into the streets of London where he felt alone, conspicuous, and nearly helpless.

Stumping clumsily down a London avenue one day late in June, a British woman and her 8-year-old son passed by. The boy's eyes took note of the crutches and then traveled down the airman's body to the empty space below the right pant leg.

"You'll never miss it, Yank!" the boy hollered as he passed, his words reverberating inside Bob Vance's mind like a horrible epithet. The British mother looked sharply down at her son, turned, and walked back to the wounded airman.

"(She) came up to me and apologized," recalled Vance in an interview for True magazine. "Then she explained that he had lost his own foot in the blitz and was getting along fine with an artificial one. That was the biggest boost I got.

"(I) felt a devil of a lot better after that."

The Making of a Model Officer: Leon Robert Vance

The meteoric rise of Leon Robert Vance in becoming one of the Army Air Force's stellar officers and commanders was no surprise to those who knew him in his youth. Bob Vance possessed all the finest qualities of leadership and combined these with a sense of self-confidence that enabled him to go from Second Lieutenant to Lieutenant Colonel in little more than four years.

The meteoric rise of Leon Robert Vance in becoming one of the Army Air Force's stellar officers and commanders was no surprise to those who knew him in his youth. Bob Vance possessed all the finest qualities of leadership and combined these with a sense of self-confidence that enabled him to go from Second Lieutenant to Lieutenant Colonel in little more than four years.

Born in Enid, Oklahoma, on August 11, 1916, Bob Vance was the hometown kid that excelled in virtually everything. His father, Leon R. Vance, Sr., served as the principal of Enid's Longfellow Middle School and believed strongly in the importance of a good education. Young Bob followed the advice of his father, studying hard and becoming an honor student. He challenged himself in high school with the most difficult classes and scored a 94% average in mathematics. The younger Vance was also strong, healthy, and gifted, excelling in virtually every sport.

After graduating from Enid High School in 1933 Vance enrolled at Oklahoma University, where his scholastic abilities qualified him to become a member of Phi Delta Theta. At OU, Vance continued to shine as an athlete, and also joined the university's ROTC program. During Vance's sophomore year one of the incoming freshmen and comrades in the ROTC program was John Lucian Smith. After graduating from OU in 1936 Smith would enter the Marine Corps to become one of the leading airmen of World War II, earning the Medal of Honor and gracing the cover of Life magazine.

While Vance excelled at OU, his goals lay more in line with the military. Bob Vance's uncle had been a decorated veteran of aerial combat who was killed in World War I. Vance's father had furthered his son's interest in following his uncle's footsteps by his own enthusiasm for flying. In addition to his role as a middle school principal, the senior Vance was also a flight instructor. While attending classes at OU, Bob Vance took a competitive exam for an appointment to a military academy. He scored very high and "Was given his choice, and chose Annapolis," recalled his wife Georgette. "True to tradition.... (he) was sent to West Point."

Vance entered West Point in 1935 where he was promptly nicknamed "Philo," for the popular fictional detective Philo Vance created by author S.S. Van Dine. During his four years at the Point, Vance continued to excel. His appearance was always immaculate, his sense of discipline keen and well-honed, his academics placed him in the top third of his class, and he excelled in virtually every sport. It was also while attending West Point that Vance met Georgette Drury Brown of nearby Garden City, New York. The two dated, romance blossomed, and the two of them began planning for a future. It was, however, a future that had to wait. Academy cadets were not allowed to marry while still attending classes.

Vance graduated in 1939 and was commissioned as an Infantry Second Lieutenant. The day following graduation he and Georgette were married at the Catholic Chapel on the Academy grounds. The young couple lived with Georgette's parents in their Garden City home while the young officer awaited further orders. It was for that reason that Garden City, New York, became the home of record for the young man who would one day earn the Medal of Honor, instead of his hometown of Enid, Oklahoma.

Vance graduated in 1939 and was commissioned as an Infantry Second Lieutenant. The day following graduation he and Georgette were married at the Catholic Chapel on the Academy grounds. The young couple lived with Georgette's parents in their Garden City home while the young officer awaited further orders. It was for that reason that Garden City, New York, became the home of record for the young man who would one day earn the Medal of Honor, instead of his hometown of Enid, Oklahoma.

When Lieutenant Vance's first orders, at last, came down, they sent him back home to attend the Spartan School of Aeronautics in Tulsa. After graduating on September 13, he was assigned to Randolph Field in Texas for Primary FTS training, graduating the following March. From there it was on to Kelly Field (Texas) where he joined Class 40C, earning his wings on June 21, 1940. When he returned to Randolph Field as an instructor in Advanced Flying Techniques, the crossed rifles of his Infantry commission had been replaced by the wings and propeller blade of an Army Air Corps Officer. On the opposite collar, the gold bar of a second lieutenant was replaced by a silver bar.

In 1935, the General Headquarters Air Force (GHQ AF) was established at Langley Field, Virginia, marking the first time that the air arm became almost autonomous within the U.S. Army. In 1938 General Henry Hap Arnold was named Air Chief and, with the prospects for a war looming, the following three years marked rapid changes in the growth of American Air Power. (In June 1941, the Air Corps was renamed the Army Air Force, though it continued to be called Air Corps throughout the war in many circles.)

Part of the expansion was the opening in January 1941 of Goodfellow Field at San Angelo, Texas, under Colonel George M. Palmer. That base was to become a training ground for many of the young men who would become the greatest air heroes of World War II. On February 4, 1941, Lieutenant Vance and Georgette moved to San Angelo where the young officer assumed command of the 49th Squadron. One of the members of the squadron's ground crew was a local boy named Mark Mathis. Mark convinced his brother Jack, who at the time was a corporal writing for the unit newspaper at Fort Sill, to transfer to Goodfellow so the two could serve together. Mark Mathis became one of the clerks in Lieutenant Vance's squadron.

Part of the expansion was the opening in January 1941 of Goodfellow Field at San Angelo, Texas, under Colonel George M. Palmer. That base was to become a training ground for many of the young men who would become the greatest air heroes of World War II. On February 4, 1941, Lieutenant Vance and Georgette moved to San Angelo where the young officer assumed command of the 49th Squadron. One of the members of the squadron's ground crew was a local boy named Mark Mathis. Mark convinced his brother Jack, who at the time was a corporal writing for the unit newspaper at Fort Sill, to transfer to Goodfellow so the two could serve together. Mark Mathis became one of the clerks in Lieutenant Vance's squadron.

The two young men worked for Lieutenant Vance for nearly a year until on January 11, 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, they departed together for aviation training at Ellington Field near Houston. Vance would never see them again, but the story of their valor in the air over Europe would come back to alternately inspire and haunt him. Both were killed in action only months apart in 1943. Mark, the younger brother, would become the first airman to earn the Medal of Honor in Europe.

The year-and-a-half the Vances spent at San Angelo provided the young couple their first stable home. Since their marriage in 1939, Lieutenant Vance's assignments had regularly shifted him from post to post. At San Angelo, they became friends with Lieutenant Horace S. Carswell and his new bride Virginia. Carswell was a native Texan who had earned his wings the previous November and was subsequently assigned as an instructor at Goodfellow Field. Virginia was a native of San Angelo and was quick to show the Vances around the area. Over the following year, the couple would develop a close personal friendship, often entertaining each other for dinner and games of Bridge. Both airmen would eventually leave San Angelo to fly combat in B-24s. Each of them would arrive in different theaters of combat in the same month in 1944 and would earn the Medal of Honor within six months of each other.

In a cruel twist of fate, both Georgette and Virginia would also become widows.

Life was good at San Angelo. Lieutenant Vance was a capable squadron commander, admired by his officers, respected by his superiors, and most of all Georgette recalled, "he was very well-liked by his enlisted men." While juggling a blossoming career, a solid social life, and building a family, Lieutenant Vance still found time to state his passion for rugged outdoor living. The backwoods of the small central Texas town afforded excellent hunting and fishing, two sports Vance had always found alternately relaxing and exciting.

"One amusing incident occurred in San Angelo when colonel Vance, who had been on a hunting trip, brought a deer back sitting in the back seat of his basic training," Georgette later recalled. "Landing at dusk it threw the ground crew into a panic as to the condition of his 'passenger'."

On December 7, 1941, the United States declared war on Japan. Two days later war was declared on Italy and Germany, and Lieutenants Vance and Carswell were confronted with the fact that the young men they trained would soon be flying into harm's way. It was a deadly serious responsibility that both officers took quite seriously, as the tempo of their lives and responsibilities took on a new urgency.

In January 1942, the Mathis brothers departed Goodfellow Field to become aviators, and the following month Horace Carswell was promoted to First Lieutenant. On April 6 Vance was promoted to Captain, and just three months later on July 17, he received the gold leaves of a Major. Regarding Vance's promotion from Second Lieutenant to Major in but three years, author Chaz Bowyer notes:

"Vance's case was made on sheer merit. An exceptional officer in every sense of the description, Vance could not be faulted in his appearance, attitudes or sheer instinctive ability to lead and inspire respect and confidence in others, be they subordinates or rank superiors. He was, in every way, an excellent living example of the 'West Pointers', yet without any blind adherence to the military 'book of rules. Off-duty, nothing pleased him more than a day of peaceful fishing--usually alone--or spending a few days teaching elementary shooting techniques to the boys attending the summer camp in Minnesota run by his father."

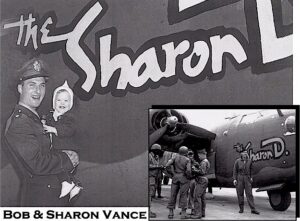

In the fall Lieutenant Carswell left for the Combat Crew School at Hendricks Field, Florida, while Major Vance continued to prepare a new wave of young men for combat duty overseas. Amid all the changes in the life of Leon Robert Vance in 1942 however, the most blessed was the birth of a daughter. Bob and Georgette named her "Sharon."

In the fall Lieutenant Carswell left for the Combat Crew School at Hendricks Field, Florida, while Major Vance continued to prepare a new wave of young men for combat duty overseas. Amid all the changes in the life of Leon Robert Vance in 1942 however, the most blessed was the birth of a daughter. Bob and Georgette named her "Sharon."

In December Major Vance was sent to Strother Field at Winfield, Kansas. Over the following nine months while he served as Director of Flying at the Basic Pilot School, he would learn that both Mathis brothers had been killed in combat and that Jack Mathis had been posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. It was presented to his mother in her hometown of San Angelo in September 1943.

Continuing reports of combat actions and the heroics of American airmen served not only to inspire Vance but also to stir in him a desire to get out from behind a desk and join the hundreds of men he had trained in aerial combat. In September Vance was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and offered assignment at Fort Worth for a one-month training in 4-engine bomber conversion; specifically training for the Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber. Lieutenant Colonel Vance, though unsure of the value of the large, multi-engine aircraft, accepted the training as a potential step towards a combat assignment. "He decided he made a wise choice when flying over Lake Worth in a P-39 whose motor kept conking out and nearly ditching itself in the lake," Georgette recalled. "His wheels were actually wet when he landed. He figured it was right smart to have a few extra motors aboard after that."

Following his training at Fort Worth, Vance was posted to duty for one month with the 29th Bombardment Group at Gowen Field in Boise, Idaho. The Very Heavy Bombardment Group was training for combat in the Pacific with B-29s, and would later include among its ranks a young Staff Sergeant named Henry Erwin, who would earn the Medal of Honor on a bombing mission over Japan.

Following his training at Fort Worth, Vance was posted to duty for one month with the 29th Bombardment Group at Gowen Field in Boise, Idaho. The Very Heavy Bombardment Group was training for combat in the Pacific with B-29s, and would later include among its ranks a young Staff Sergeant named Henry Erwin, who would earn the Medal of Honor on a bombing mission over Japan.

For his own part, despite increasing frustration that the war might end before he saw combat, the Medal of Honor was never far from Lieutenant Colonel Vance's thoughts, or personal goals. "While still trying to get out of the Training Command for combat duty," Georgette recalled, "and having no decorations except the 'Yellow Fever' and an Expert Pin with numerous bars for prowess with various types of firearms, he would look enviously at the personnel in the 2nd AF Hqs with all their war decorations and maintain that someday he would have all that the MH too..."

During the month Vance was assigned to the 29th Bombardment Group in Boise, German pilots and ground gunners in Europe were demonstrating there was still plenty of wear remaining. The fateful October 17 mission over Schweinfurt during which sixty American bombers fell to enemy guns both in the air and on the ground, demonstrated clearly that the war was far from over. Meanwhile, virtually everyone on both sides of the Atlantic whether civilian or military was keenly aware that the long-anticipated landing of Allied ground troops in occupied France could not be far away. In fact, in the most secret enclaves of the Allied high command, D-Day had already been set for May 1944, just six months away. The date had been agreed upon when President Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin met for the Teheran Conference in late November.

With American bombers falling in record numbers, with the "Point Blank" directive to neutralize the Luftwaffe and gain aerial superiority over France behind schedule, and with the imminent demand for aerial support for the coming D-Day invasion, the Army Air Force worked quickly to reinforce its 8th and 9th Air Forces in England. Scores of new bombardment groups were being hastily assembled and trained to support Operation Overlord. One of them was the 489th Bombardment Group (Heavy) at Wendover Field, Utah.

In December Lieutenant Colonel Vance was reassigned to the 489th as Deputy Commander of the Group. He was tasked with preparing the B-24 Liberator pilots and crews for actions in support of the D-Day landings. In only four months the group was combat-ready, and by April Lieutenant Colonel Vance said his last goodbyes to Georgette before flying to England. His own aircraft was named for his daughter Sharon, and with the year-old toddler, he posed for one final photograph before heading for war in a Liberator named...

The Sharon D: Bombs Over Berlin

Lieutenant Colonel Vance and the men of his 489th Bombardment Group were in the final phases of their training when headlines announced news of the March 6, 1944, raid on Berlin. Prior to the war Luftwaffe commander, Hermann Goering had boasted that no bombs would ever fall over Berlin. The Nazi capital was the most-heavily-defended city in the world. Even as American bombers began striking closer and closer into the heart of Germany in the fall of 1944, Goering reassured his Fuhrer and the people of Germany, "If enemy bombers ever appear over Berlin you can call me Meier."

By 1944 the "Big B," as the target was known among airmen of the Mighty Eighth, was ringed by hundreds of anti-aircraft guns. Thousands of German fighter aircraft, piloted by some of the Reich's most seasoned and skillful pilots, were prepared to shoot down anything that ventured towards Berlin by land or air.

By 1944 the "Big B," as the target was known among airmen of the Mighty Eighth, was ringed by hundreds of anti-aircraft guns. Thousands of German fighter aircraft, piloted by some of the Reich's most seasoned and skillful pilots, were prepared to shoot down anything that ventured towards Berlin by land or air.

In fact, the R.A.F. had conducted night-bombing missions against Berlin since early in the war. These dangerous raids, despite the damage they inflicted, were more of a nuisance than a threat. But when General Jimmy Doolittle had the audacity to dispatch some 700 bombers to attack Berlin in broad daylight, it was a certain sign that the Luftwaffe was in demise and that the Reich continued to exist, only on borrowed time.

In fact, though hailed at the time as the first American bombers to hit the Big B, the March 6 raid was not the first. On March 4, buoyed by the tremendous success of "Big Week" the previous month, the first daylight attack was mounted. Deteriorating weather forced the mission to be recalled, but 29 bombers did not get the recall order and continued on to Berlin with their P-51 escorts. Their impact was minimal. Two days later, however, 660 heavy bombers appeared in the skies over Berlin to drop their lethal cargo. Doolittle lost 69 bombers, the highest single-day loss of the war by the Mighty Eighth, along with 11 fighters lost. Nonetheless, the mission was a tremendous success, both militarily and psychologically. For the American public, it provided news that the third of the three major Axis Power capitals had been struck by American bombers. To the German people it had a very demoralizing effect, confirming that the tide of the war had turned against Hitler and his Reich.

For General Doolittle, it was a bitter-sweet victory. Nearly two years earlier, on April 16, 1942, Doolittle's Raiders had been the first to bomb Tokyo. The following year on July 19, as commander of the 15th Air Force in the Mediterranean, General Doolittle had led the first bombing raid over Rome. He argued long and sincerely for permission to make it a trifecta by leading the first raid over Berlin. It was one of the few battles the gutsy pilot ever lost. With plans well underway now for the cross-channel attack, and with the highly classified knowledge of that mission the new 8th Air Force commander carried in his head, Tooey Spaatz refused to succumb to Doolittle's persistence.

The initial Battle of Berlin, a bombing campaign that might well be seen as "payback" for the Luftwaffe's 1941 Battle of Britain, lasted only from March 4 to 9. Before the end of World War II, however, the air war over Berlin would resume with such fury that 75% of the city was destroyed. But in the spring of 1944, there were greater priorities than turning Hitler's headquarters into a pile of rubble. With the D-Day invasion scheduled for May, the top priority was placed on continuing to hit aircraft production facilities and petroleum production facilities. With Allied ground troops preparing to land on German-held soil, it was critical to keep the Luftwaffe from replenishing the hundreds of airplanes already lost and to deny fuel to those aircraft (as well as ground vehicles and tanks) that remained.

The Mighty Eighth kept the pressure on, mounting near-daily missions throughout March and April. Missions were still occasionally mounted against targets deep inside Germany, but the majority of missions were flown against targets in France, Belgium, and Holland. In addition to the destruction wreaked on the ground by Allied bombs, Luftwaffe fighters continued to fall in great numbers as they fought in vain to stem the Allied air advance. On March 18 alone, American pilots claimed 84 enemy aircraft were destroyed. Indeed, in virtually every mission American B-17s, B-24s, and escorting fighters were also lost. But American factories continued a steady stream of new airplanes into Great Britain. With the attacks on German factories, however, the Luftwaffe never recovered from their losses after Big Week.

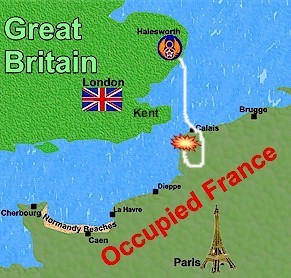

On April 3 Lieutenant Colonel Vance assembled the crew of his B-24 Liberator "Sharon D." With Lieutenant Baker in the co-pilot's seat, Vance turned his airship south, then east, and then north. The route to England, and into a still-deadly war, was made by the southern ferry route: South America, then across the South Atlantic to Africa, and then north to the 489th's new home at Halesworth in Great Britain.

Leon Vance's Crew

Standing (L-R) Pomles, Vance, Baker, Winfield, Holub, Denyes

Kneeling (L-R) Mersch, Shippe, Brieda, Lewis

The aircrews' first weeks in England were filled with additional training while awaiting the arrival of the ground crews who traveled to England from New York aboard the USS Wakefield. Each day Vance's men would watch as hundreds of bombers took off from airfields like their own to form up and cross the channel to fly into deadly flak and fend off German MEs and JUs to reach their targets. All of the men were keenly aware that some of the bombers that departed in the early morning sunshine would not be coming back. Each of them also knew that the day was not far away when "Sharon D" would be in the midst of one of those formations.

All across England, it was difficult not to be aware that something big was in the wind. In anticipation of the May D-Day invasion that everyone, both civilian and military; whether American, British or German, knew was coming, there was an eagerness to get out of the training rooms and into the battle. In those months more than 3 million men streamed into England for their assigned roles in Operation Overlord. Based across the island were 80,000 trucks, 10,000 tanks, 5,200 bombers, 2,400 transport planes, and 5,500 fighter aircraft. Only half-jokingly it was often noted that Great Britain was in danger of sinking into the sea under all the weight. Offshore there were 1,200 naval ships, 2 battleships, 23 cruisers, 105 destroyers, and 2,500 landing craft. The only thing secret about D-Day was when and where. As for the when everyone knew it would be soon.

On April 22, a top-secret rehearsal for D-Day was held near South Devon. Codenamed Exercise Tiger; it was as real as preparation for the landings at Utah Beach as could have been planned. The surf and sandy beach at Slapton Sands were nearly identical as could be found to one of the five planned Allied invasion sites. For five days 30,000 American soldiers loaded on the same ships and in the same ports from which they were planned soon to depart for Northern France. On the night of April, 26 minesweepers led the main force into the friendly waters of Lyme Bay, and the American soldiers hit the beach with the dawn on April 27. A second assault force was scheduled to land with dawn the following morning. In the pre-dawn darkness of April 28 however, nine German E-boats (similar to American PT-Boats) slid into Lyme Bay to unleash a torrent of torpedoes. In minutes two LSTs were sunk and a third heavily damaged. In all, 551 soldiers and 198 sailors were killed. To the few who were aware of the incident (it was neither reported nor was casualty information released until the following August), it presented a foreboding omen to the planned, real invasion.

By early May the continuing poor weather, the recent lessons of Exercise Tiger, and unfolding events in the Italian campaign convinced the Allied High Command to postpone Operation Overlord for a month and D-Day was set for June 5. The postponement gave critically needed time for dealing with the heavy logistical demands of 3 million troops. It also gave important time to the Allied disinformation specialists, tasked with deceiving German spies as to the date and more importantly, location, of the impending invasion. Furthermore, it gave the men of the 8th and 9th Air Forces one more month to hammer German facilities and to shoot down enemy fighters.

"Because the tempo of our attacks increased," General Doolittle recalled, "the Luftwaffe was well aware that an invasion was imminent. To prevent the enemy from knowing where it would take place, we did not focus on any single target system within the invasion arc. In the 15 days prior to D-Day, the 8th attacked 52 airfields, 45 marshaling yards, and 14 bridges. In addition, six attacks were made on coastal fortification and four on gun positions."

Among those missions in the last two weeks before D-Day was a May 30 mission against the airfield at Oldenburg, Germany. The Eighth Air Force sent 135 heavy bombers across the North Sea to hit that target a few miles south of Wilhelmshaven, while equally large formations struck at other targets in Europe. It was the first combat mission for the 489th group, a mission that was highly successful despite the loss of one 489th Liberator. It was the Group's first casualties with two men killed and eight captured after parachuting to safety and the only loss of the 135 bombers from various groups dispatched to Oldenburg. Group leader for the 42 B-24s from the 489th Bombardment Group assigned to the Oldenburg raid was Lieutenant Colonel Leon Bob Vance in "Sharon D." It was destined to be not only his first but last combat mission in the bomber named for his infant daughter.

Prelude to Overlord

In November 1943 Adolph Hitler appointed Field Marshall Erwin Rommel to be the Inspector of Coastal Defenses in France, and then later appointed him Commander of Army Group B which occupied these coastal defenses along the northern coastline. The legendary German hero of North Africa arrived in France in December and immediately began improving these defenses. He endeavored to create an impassable zone, initially 100 meters deep, along the whole channel coast with hopes to eventually extend its depth to a kilometer by the laying of 200 million mines. He dramatically accelerated the rate at which beach obstacles were constructed and by May 11th, more than half a million had been raised along the channel foreshore and on likely glider and parachute landing zones behind the beaches. Additionally, some areas immediately behind the beaches were inundated with water to further inhibit any movement off the beaches and to contain the attacker’s beachheads.

Hitler's plan to thwart the impending Allied invasion that he knew would come early in the next year was outlined in the same November 3 directive giving Field Marshall Rommel this new role. Fuehrer Directive 51 noted:

"The threat from the East remains, but an even greater danger looms in the West: the Anglo-American landing! If the enemy here succeeds in penetrating our defenses on a wide front, consequences of staggering proportions will follow within a short time. All signs point to an offensive against the Western Front of Europe no later than spring, and perhaps earlier...I have therefore decided to strengthen the defenses in the West, particularly at places from which we shall launch our long-range war against England. For those are the very points at which the enemy must and will attack; there-unless all indications are misleading-will be fought the decisive invasion battle."

The sustained Allied bombing campaign of early 1944 seriously curtailed German production of war materials, and the effective aerial prowess of newly arrived P-51s had taken a serious toll on the Luftwaffe's resources to resist the coming invasion from the air. Nonetheless, occupied France remained a stronghold of Nazi military might and by May 1944 Hitler had 59 Divisions spread across the region. The Fuehrer and his top commanders, however, could only guess at the when and the where of the impending invasion.

American air missions leading up to the invasion, therefore, had to be multifaceted. Foremost, they were practical missions--bombing raids to further weaken the enemy supply of war material and infrastructure: vehicles, railroads, bridges, and petroleum. Secondarily but equally important, they were tactical missions, assigned to strike a balance between targets in the vicinity of the planned landing and diversionary targets to avoid exposing the secret of that landing site.

The precarious balance of these assigned missions is quickly evident in Eighth Air Force Field Order 709 for the June 2 air missions. It stated:

"All objectives were located in the Pas de Calais (Fortitude) area, the attacks having as their purpose deception of the enemy as to the actual assault area. (Cover Plan.) It was provided that in these operations immediately preceding D-Day only one-half of the available heavy bombers were to be employed in order to conserve the force for an all-out assault in direct support of the troop landings."

The practice and goals established in that June 2 Operations Order reflect the manner in which all air operations were planned and conducted in the final week before D-Day. The term "Fortitude" mentioned in that order referenced a top-secret effort to deceive the German intelligence effort to correctly predict the site of the Allied invasion. That effort was code-named "Fortitude South."

Beginning in 1943, a skilled team worked to create the illusion of a large invasion force being massed at Kent in England. Dummy tanks and aircraft were built of inflatable rubber and placed in realistic-looking "camps". Harbors were filled with fleets of mock landing craft. To German reconnaissance aircraft, it all looked real, even down to attempts at camouflage. Knowing that German intelligence would be trying to find out more, double agents planted stories and documents with known German spies. General George Patton was supposedly commander of the non-existent force and realistic radio transmissions were broadcast as if a large army were being organized.

Beginning in 1943, a skilled team worked to create the illusion of a large invasion force being massed at Kent in England. Dummy tanks and aircraft were built of inflatable rubber and placed in realistic-looking "camps". Harbors were filled with fleets of mock landing craft. To German reconnaissance aircraft, it all looked real, even down to attempts at camouflage. Knowing that German intelligence would be trying to find out more, double agents planted stories and documents with known German spies. General George Patton was supposedly commander of the non-existent force and realistic radio transmissions were broadcast as if a large army were being organized.

The overall effect was to convince German intelligence that the invasion would be launched against Pas-de-Calais, the French port situated at the point where the English Channel is at its narrowest point. Ultimately, the ruse was successful far beyond what Allied commanders could have hoped. The bulk of the German defensive forces were concentrated near Calais. So convinced was the Nazi high command that Calais would be the site of the D-Day invasion when the actual landings did occur but far to the southwest at Normandy, the Nazis continued to prepare to defend Calais in the belief that the Normandy landings were a diversion. As a result, in the first critical 24 hours of D-Day, tens of thousands of German troops were kept in their fortifications at Calais, rather than rushed to the site of the actual invasion.

The overall effect was to convince German intelligence that the invasion would be launched against Pas-de-Calais, the French port situated at the point where the English Channel is at its narrowest point. Ultimately, the ruse was successful far beyond what Allied commanders could have hoped. The bulk of the German defensive forces were concentrated near Calais. So convinced was the Nazi high command that Calais would be the site of the D-Day invasion when the actual landings did occur but far to the southwest at Normandy, the Nazis continued to prepare to defend Calais in the belief that the Normandy landings were a diversion. As a result, in the first critical 24 hours of D-Day, tens of thousands of German troops were kept in their fortifications at Calais, rather than rushed to the site of the actual invasion.

Air missions, such as the June 2 raid against targets in the vicinity of Pais de Calais, helped to further reinforce the aims of Fortitude South in convincing the enemy that the attacks were bombardments preparatory to an amphibious assault on the region. These diversionary missions were code-named Operation Cover and would continue until D-Day. The fact that they were diversionary in nature certainly did not, however, decrease their danger. So effective had the Allied deception become that the Calais area was the most fortified and heavily armed Nazi stronghold outside of Berlin. On June 2, the 489th Bombardment Group flew the third of its total 106 missions of the war. In a total of 2,998 sorties over enemy territory from May 30 until the end of the war, the group lost 26 bombers. On June 2 they suffered their heaviest single-day casualty rate of the war: 4 bombers destroyed, 3 badly damaged, 21 airmen killed, 5 wounded, and 6 captured by the Germans. One entire crew bailed out over England. Lieutenant Colonel Vance was not on the schedule for the operation and missed the action.

On June 3, (then) D-Day minus 2, two separate Operation Cover missions were flown. The 489th Bombardment Group got a day of rest, while more than 500 heavy bombers from other groups attacked coastal defenses near Calais in two separate missions. Despite heavy and accurate anti-aircraft fire over the heavily defended region, no bombers were lost.

Sunday, June 4, was supposed to be the day prior to the invasion, "D-Day minus 1." Eighth Air Force assets were divided between two missions: Operation Cover to continue bombardment in the Calais area, and Operation Neptune, the actual channel-crossing phase of Overlord. Poor weather continued across the channel, however, and with a low ceiling, heavy rain, and high seas, the D-Day landing was postponed for 24 hours. The Neptune air missions were canceled, but more than 900 bombers in three separate operations, attacked northern France. The first two waves hit targets in the Calais area. Later in the day the third, with more than 400 heavy bombers, attacked railways and bridges throughout northern France. Again, despite the heavy anti-aircraft fire, no heavy bombers were lost. Twenty-six Liberators of the 489th Bombardment Group joined in these assaults, but also again, Lieutenant Colonel Vance was not on the roster. Instead, he was scheduled to lead the following morning's raid.

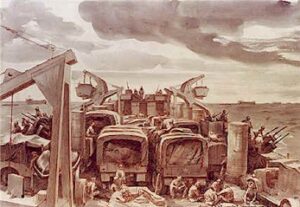

By sunset on the evening of June 4 the troops, trucks, tanks, and other supplies had been loaded for transport across the English Channel. Nervous young men crammed the decks, some sleeping inside covered trucks to try and remain dry, others forced to survive the continuing rainfall. Under the most favorable of conditions, however, sleep would have been nearly impossible. All involved knew that within 24 hours they would most likely be embarking on the most dangerous venture into the unknown that they would ever experience.

By sunset on the evening of June 4 the troops, trucks, tanks, and other supplies had been loaded for transport across the English Channel. Nervous young men crammed the decks, some sleeping inside covered trucks to try and remain dry, others forced to survive the continuing rainfall. Under the most favorable of conditions, however, sleep would have been nearly impossible. All involved knew that within 24 hours they would most likely be embarking on the most dangerous venture into the unknown that they would ever experience.

At 0415 Monday morning General Eisenhower and the top Allied commanders of SHEAF gathered for an update on weather conditions. The forecast was promising, though not as good as the commanders had hoped. In fact, so marginal was the weather at that moment that ultimately it convinced the Germans that the Allied invasion could not be accomplished in the coming days, prompting Field Marshall Rommel to travel to Berlin, where he was meeting with the Fuehrer at the moment the first Allied soldiers waded ashore at the five Normandy invasion beaches.

After hearing the reports and discussing the options with his commanders, General Eisenhower announced his decision with a smile: "All right boys, we'll go."

Meanwhile at airfields all across England, in the predawn chill, scores of B-24 Liberators and B-17 Flying Fortresses began warming their engines for one last mission before D-Day. In all some 629 heavy bombers were assigned to attack coastal defensive installations at Cherbourg to the west of the invasion beaches, similar targets in and around Calais northeast of the invasion site, as well as 3 V-weapons sites and a railroad bridge further inland. Mission 4 for the newly arrived 489th Bombardment Group was shaping up to be a "milk run." Thirty-six of the Group's Liberators were scheduled to lead the attack on enemy coastal defenses at Wimereaux a few miles south of Pais de Calai. From their airfield at Halesworth is was barely 100 miles to target, most of the trip over the water of the channel and with very little time over occupied France where some remaining Luftwaffe fighters were poised for a final, desperate attack.

Lieutenant Colonel Leon Vance had been assigned air group commander for this mission, his second combat mission since arriving in England. In this role he would ride, not pilot, the lead bomber--and his aircraft was not the Sharon D. The lead bomber had been christened "Missouri Sue" but bore no markings to identify it other than the tail numbers 42-294830 and the white letter "A" in a circle, indicating that it was from the 44th Bombardment Squadron.

Flying Eight Balls

The 44th Bombardment Group, the first B-24 group in the U.S. Army Air Force, was based out of Shipdham some 40 miles west of Halesworth. It was a veteran group that had distinguished itself in combat since its arrival in October 1942. Adding the two "fours" from their Group number the airmen achieved a sum of "8" and therefore called themselves the "Flying Eight Balls." Early on their rivals in the 93d Bombardment Group, a Liberator group that was organized after the 44th but that had preceded them in combat by one month took to calling them the "Flying Odd Balls." In the years and missions that followed the 93d and 44th would maintain a constant rivalry. To many of the Flying Odd Balls, it seemed like the 93d, known as the Traveling Circus, got all the media attention, while the 44th got all the dangerous missions and suffered the highest casualties.

The 44th Bombardment Group, the first B-24 group in the U.S. Army Air Force, was based out of Shipdham some 40 miles west of Halesworth. It was a veteran group that had distinguished itself in combat since its arrival in October 1942. Adding the two "fours" from their Group number the airmen achieved a sum of "8" and therefore called themselves the "Flying Eight Balls." Early on their rivals in the 93d Bombardment Group, a Liberator group that was organized after the 44th but that had preceded them in combat by one month took to calling them the "Flying Odd Balls." In the years and missions that followed the 93d and 44th would maintain a constant rivalry. To many of the Flying Odd Balls, it seemed like the 93d, known as the Traveling Circus, got all the media attention, while the 44th got all the dangerous missions and suffered the highest casualties.

The Group earned its first Distinguished Unit Citation eight months after it entered combat while flying in the wake of the main formation during a daring May 14, 1943, raid against enemy shipping installations at Kiel. In June, the group was one of three Eighth Air Force Liberator Groups, including the 98th BG, detached for service with the 9th Air Force in North Africa. On the daring August 1 low-level raid over Ploesti, Rumania, the Group suffered heavy casualties including ten aircraft lost and earned a second Distinguished Unit Citation. Their commander, Colonel Leon Johnson was one of five airmen in that one massive air mission who earned the Medal of Honor.

The Group earned its first Distinguished Unit Citation eight months after it entered combat while flying in the wake of the main formation during a daring May 14, 1943, raid against enemy shipping installations at Kiel. In June, the group was one of three Eighth Air Force Liberator Groups, including the 98th BG, detached for service with the 9th Air Force in North Africa. On the daring August 1 low-level raid over Ploesti, Rumania, the Group suffered heavy casualties including ten aircraft lost and earned a second Distinguished Unit Citation. Their commander, Colonel Leon Johnson was one of five airmen in that one massive air mission who earned the Medal of Honor.

Following the Ploesti raid, the group remained in North Africa in support of the Salerno operations for two months. Following the heavy losses over Ploesti, new bombers and crews began arriving quickly, including Captain Louis Mazure. Mazure flew missions in September before the 44th Bombardment Group returned to the Mighty Eighth in England in October, one year after they had arrived initially to begin combat operations.

Captain Mazure and other airmen of the 44th BG flew during Big Week, as well as throughout the early Spring 1944 campaign to pave the way for Operation Overlord. The Flying Eight Balls had been seasoned by both triumph and tragedy. On a March 14 mission eight heavy bombers were lost, and the following month on April 8 the Group suffered its heaviest single-day losses of the war when eleven out of twenty-seven bombers dispatched on a mission over Germany were lost. Ultimately the group would end the war with the highest Missing in Action loss (153 heavy bombers) of all the 8th Air Force's B-24 Groups. Conversely, the Group operated out of England longer than any other Liberator Group and was credited with shooting down 330 enemy fighters, the Mighty Eighth's record for any B-24 group.

The winter weather in Europe seemed to ally itself to the Axis. Constant cloud cover often grounded Allied bombers, which normally made their runs into the target using the visual capabilities of the Norden Bomb Sight, for four out of every five days during the months of November through April. The problem led to the development of radar for identifying ground targets through the overcast. To facilitate "Blind Bombing," sometimes called "BTO" (Bombing Through Overcast), the Eighth Air Force established a Pathfinder Force (PFF). The technique called for a highly-skilled aircrew in a modified aircraft to lead the way, identify the target, and unleash its load. The trailing aircraft in the bomber stream then "bombed on the leader," trusting the skill of the PFFs to ensure that they had not flown all this way and risked their lives in vain--only to unload on barren land or empty water.

The B-24s of the 44th Bombardment Group's 66th Squadron were modified with the equipment necessary for radar identification of targets. Special, highly trained navigators were assigned to these bombers, and the most experienced aircrews were assigned to pilot and defend what was to become the 44th Bomb Group's, Pathfinder Force. In May Captain Mazure was assigned to pilot one of these PFFs, and given a crew that had flown 14 missions with the 93d Bombardment Group before being sent to the 66th squadron. They were joined by Lieutenants Bernard Bail and Nathaniel Glickman, both of whom were highly trained in radar and navigation.

On the early morning of July 5, Captain Mazure's crew was preparing for their third PFF mission after more than a month of specialized training in May. Their first two PFF missions had been on June 2 and 3, followed by a single day of rest. With the arrival of several new and inexperienced Bombardment Groups in England, crews of the 66th Bombardment Squadron were regularly assigned as PFFs for the new arrivals. Such was to be their role in the mission the 489th BG had been tasked with leading into Wimereaux.

Captain Mazure's co-pilot Lieutenant Earl Carper, known to his friends as Rocket, wasn't too excited about taking aboard the Air Group commander, a Lieutenant Colonel from the 489th Bomb Group that none of them knew. This reluctance, however, was not because the man was unknown. Rocket knew that the air group commander usually flew in the right-hand seat of the lead PFF, forcing the co-pilot to "stand by" at the waist. It made for an unusually cold and almost always uncomfortable sortie. Rocket tried to comfort himself with the knowledge that today's target lay only 100 miles distant. In all, the round trip would take less than two hours, a welcome break from the eight-to-ten-hour missions he had flown all too often.

Dawn was beginning to break as Captain Mazure's crew gathered at their bomber and looked off into the distance. The briefing had been at 0400 with the announced target as Wimereaux, and the bomb load identified as ten 500-pound bombs. Four-and-a-half hours after the briefing began the crew had assembled. In the early haze, they noted the arrival of a tall, lean lieutenant colonel who walked with confidence and had the immaculate appearance of a classic West Pointer. Lieutenant Colonel Vance introduced himself to Captain Mazure, then shook hands with the other officers and enlisted crew of the lead bomber for the day's mission. Then Vance gave

Rocket a totally unexpected surprise when he announced, "You'll fly in your normal position as co-pilot. I'll stand behind to observe."

The crew then boarded to prepare for their 0900 takeoffs, Lieutenant Bernard Bail (Lead Radar Navigator), and Lieutenant John Kilgore (Navigator) taking their positions on the flight deck behind the pilot and copilot. Lieutenant Milton Segal (Bombardier) assumed his position in the clear Plexiglas nose alongside Pilotage Navigator Lieutenant Nathaniel Glickman. As the PFF lead upon whose bomb drop the following Liberators would unload their own ordnance, these specialized officers numbered two more than a typical bomber crew.

The radioman was Technical Sergeant Quentin Skufca, and Technical Sergeant Earl Hoppie was the flight engineer, stationed in the top turret. Waist guns were manned by Staff Sergeants Davis Evans and Harry Secrist, while Staff Sergeant Wiley Sallis slipped his slim frame into the small compartment behind the tail turret. With Lieutenant Colonel Vance positioning himself behind the pilot and co-pilot in the cockpit, it meant that the lead bomber would carry a crew of twelve, two men more than the typical Liberator compliment.

Captain Mazure warmed his engines while awaiting the signal to take off. Then, into the early morning skies, he led the way up above the low clouds, climbing to 10,000 feet. A short time later Lieutenant Colonel Vance released the flare to assemble the formation while Captain Mazure headed south for the brief trip over the English Channel, climbing to the 22,500-foot bombing altitude the mission had specified. "We're on our way," Lieutenant Kilgore announced over the interphone, and then in what seemed only a few minutes, they were over enemy-held territory.

The bomber stream continued inland as if their target lay beyond the coast, Lieutenant Bail plotting their course and then ordering a turn to approach Wimereaux from the south. Flak was light and nearing the IP, control of the aircraft was turned over to Lieutenant Segal who ordered the bomb bay doors opened. Minutes later he announced, "Bombs away," and from that point on it was a straight shot back to England, the following Liberators preparing to unload their own bombs as they headed for home.

Then over the interphone came the voice of Sergeant Hopie announcing, "Bombs away, hell. They didn't release." The malfunction not only spared the enemy emplacements on the ground below from Missouri Sue's 5,000-pound bomb load but the from the loads carried by every bomber that followed. It was the PFF's bombs that were the signal to that behind, and lacking that signal, the entire formation was winging out over the English Channel to jettison their cargo into the water as previously ordered during the morning briefing.

"Take her back around for another pass," Lieutenant Colonel Vance advised Captain Mazure. Slowly the lead bomber began a 360-degree turn, the rest of the formation following as the stream prepared for another pass.

This time the enemy defenses were on high alert. Positioned in the nose turret, Lieutenant Glickman could see that they were flying into a maelstrom of deadly accurate anti-aircraft fire. In the radio room Sergeant Skufca, the following procedure during the bomb run, turned off his radios and sat down on the step just outside his mid-fuselage compartment. Suddenly hot metal streaked upward through the floor, destroying the radio equipment and knocking away Skufca's oxygen mask by its brute force. Pain stabbed at his legs, now torn by multiple fragments of metal. Fighting a rush of dizziness, he staggered towards the waist to get oxygen from the auxiliary supply, nearly falling in the process.

This time the enemy defenses were on high alert. Positioned in the nose turret, Lieutenant Glickman could see that they were flying into a maelstrom of deadly accurate anti-aircraft fire. In the radio room Sergeant Skufca, the following procedure during the bomb run, turned off his radios and sat down on the step just outside his mid-fuselage compartment. Suddenly hot metal streaked upward through the floor, destroying the radio equipment and knocking away Skufca's oxygen mask by its brute force. Pain stabbed at his legs, now torn by multiple fragments of metal. Fighting a rush of dizziness, he staggered towards the waist to get oxygen from the auxiliary supply, nearly falling in the process.

Sergeant Siegrist reached out to steady his friend while gasoline began to spray from ruptured fuel lines as if the waist position were a shower room. "Skuf was lying on the waist floor in gas," he recalled. "I put the spare parachute under his head and immediately after I stood up, a large burst of flak came through the side of the waist and passed between Skuf and me. It made a hole in the wall about ten inches wide, then it made several holes in the left side of the waist." On the flight deck, Sergeant Hoppie was standing on his flak vest when more shrapnel ripped through the floor, knocking him off his feet. Only the cushion of the vest spared his life.

"At this same instant my nose turret took a series of bursts that shattered the Plexiglas and cut open my forehead, as well as hitting the base of my spine," recalled Lieutenant Glickman. "Our plane continued to be hit as we stayed on the bomb run. My primary concern was the possibility of our bomb bays being hit before the bombs were released." Another burst turned the turret to the side. "I can't see," Glickman shouted into the microphone as blood flowed from his forehead and into his eyes, while anxious arms tried to crank the turret back around.

By now Missouri Sue was over the target and Lieutenant Segal hit the salvo released to jettison the load. Nine 500-pound bombs began their rapid freefall as more flak shook the bomber. Over the interphone came the voice of Sergeant Siegrist announcing, "Skufca's been hit. His legs are in a bad way."

But the worst damage had occurred in the cockpit. Hot shrapnel from a blast beyond the left wing tore into the cockpit, slicing into Captain Mazure's head just below the helmet. It happened in the same moment that Segal, following the downward path of the bombs announced, "We hit it right on the nose!"

"Good boy," Mazure managed to shout into his microphone. They were his last words as he slumped forward, instantly dead.

Lieutenant Carper immediately took control, fighting to steady the flying wreckage that moments earlier had been a stout B-24. Colonel Vance shouted into the microphone, "Pilot to engineer: Number One engine is smoking. Shut off the fuel." Then came more explosions, one of them ripping into the floor and sending a ripple of pain through the air group commander's right leg as he stood behind the two seats in the cockpit. Through the window he could see that the Number One engine had ceased turning, one propeller blade sheered away and the remaining three dangling helplessly. Two more engines were out and the fourth engine appeared about to fail. Lieutenant Carper had his hands full just trying to keep the bomber level, so Vance leaned forward to try and feather the engines before the bomber could go into a stall.

Leaning forward with all his strength, something seemed to be holding him back, denying him the necessary few inches required to shut down the engines. Looking quickly backward he found the reason for the pain he had felt moments earlier. His ankle had been nearly severed when the flack ripped through the floor. The useless foot, attached now to his leg by only the Achilles tendon, was wedged between the ship's armor plate and the turret wreckage. In a supreme effort of will Vance lunged forward again, this time reaching the controls and shutting down the engines.

The bomber had cleared the target area and was now headed out over the English Channel. Though it had dropped 5,000 feet in the scant seconds during which the bombs had been released, three engines had been shot out, the pilot killed, and at least three crewmen wounded, the sturdy Liberator was responding to Rocket's skillful mastery of the controls in an effort to glide closer to England. Because of the short distance, despite the fact that a B-24 was far too heavy to be an effective glider, Carper hoped to reach the distant shores for an emergency crash landing. Then the news became even worse. Fuel continued to spray through the fuselage and the bomb bay doors were still open with one 500-pound bomb that had failed to release hanging precariously.

Lieutenant Kilgore recalled, "Hoppie, our engineer, literally 'slithered' out of the top turret, grabbing what I thought was a flight jacket and trying to stem the flow of gasoline with one hand, turning off the fuel transfer valves with the other... I got up from my seat and looked into the cockpit area, found Mazure slumped in his harness and his instrument panel was covered in blood. Carper was in the co-pilot position, doing what all good co-pilots do, trying to keep the plane flying. I then jumped down into the 'well' of the flight deck alongside Hoppie--not that I could assist him in any way, but to be first in line. Hoppie didn't need any help as he was a true professional and knew his job well."

Sergeant Hoppie was indeed occupied at this point in a critical effort to keep his airplane from erupting into flames. Gathering rags from whatever he could find, he began stuffing them over ruptured fuel lines to stem the continuing shower of gasoline. Aviation fuel sprayed into his eyes with a stinging fury that threatened to blind him. Suddenly the bomb bay doors began to close. Fearing the action would ignite a spark or worse, detonate the armed bomb that still hung in place, Hoppie grabbed the manual crank to reopen the doors while Kilgore shouted into the intercom to warn of the precarious situation.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Bail managed to reach Vance and begin administering first aid. The bomber was nearing land and Carper rang the bail-out bell. One by one the members of the crew began to jump from their damaged airplane. Sergeant Sallis had crawled forward from the tail and helped the injured Skufka to the bomb bay where both stepped into the void to fall earthward. Sergeant Davis went out the right waist window and Sergeant Secrist jumped from the left. One by one the officers made their exits as well, save for the dead pilot, the badly injured Command Pilot, Lieutenant Bail who was still treating Vance's wounds, and Lieutenant Glickman who was still trapped in the nose turret. Technical Sergeant Hoppe was preparing to jump from the open bomb bay doors when he noticed that his parachute pack was soaked in gasoline. It was too late to try and find a spare so, taking his chances, he tucked his body into a ball and rolled downward to begin his freefall.

Even in their exit, the crew continued to be plagued by misfortune. After opening his chute Sechrist narrowly missed colliding with a barrage balloon before at last landing--in a minefield. Perhaps his only good fortune was that in landing he broke his leg. The fracture kept him from trying to walk out, an act that would surely have killed him. Skufca recalled regaining consciousness as he plummeted earthward. "It was like awakening from a snooze on a hot summer afternoon and finding yourself falling out of the hammock," he recalled. "I clutched for something solid. There was nothing solid to hold on to. The funny part of it is that I actually laughed-- like all hell when I pulled that ripcord and saw the thing open." Lieutenant Kilgore also broke a leg, in two places, upon landing.

Technical Sergeant Hoppe went into a free-fall for quite a distance before reaching for the ripcord. Aware that his clothes and parachute were soaked in gasoline, he prayed that the free-fall would accelerate the evaporation of the flammable mixture while also hoping that static electricity in the air would not ignite it. When at last he pulled the ripcord…nothing happened! The wet silk remained tightly bundled inside its sodden pack.

Fighting to think clearly and remain calm, Hoppe began to claw at his pack, removing the silk in handfuls as it began to steam out above him. Then he felt a sudden relief when the canopy snapped open with a loud pop. "I can't remember what I yelled. It was the way you yell when you're on a roller coaster. It helped me realize that I was still alive," he later told a journalist.

Looking around as he floated earthward, Hoppe counted the other parachutes around him. There were seven open canopies counting his own. Above, the doomed Missouri Sue had turned towards the sea with five men still aboard.

In the cockpit, Lieutenant Bail had used a belt as a tourniquet to stem the flow of blood from Lieutenant Colonel Vance's nearly severed foot and sprinkled sulfa powder over the exposed flesh. With time running out, Lieutenant Carper, believing that the rest of the crew had safely jumped, ordered Bail and Vance to prepare to exit themselves. The co-pilot went first, landing in the water where he became entangled in the shrouds of his chute and would have drowned had not a Spitfire pilot who was circling the area remained where he could guide a rescue boat to the barely afloat co-pilot.

Lieutenant Bail recalled, "When only Colonel Vance and I remained, I told Col. Vance that we must now jump as there was no way to land that damaged plane, especially with those bombs hung up in the bay, armed and ready to explode on impact. Not being a doctor then, I was not fully aware that the Colonel was in shock. When the Colonel shook his head and said he wouldn't jump, I knew that there was no way I could drag him to the bomb bay, and assist him out. I knew, too, that the plane was losing altitude fast, and we didn't have much time. I checked his tourniquet, shook his hand, and made my plunge through the open bay."

In fact, one other crewman remained aboard. Lieutenant Glickman stated, "I was the last man to bail out inasmuch as I was trapped in the nose turret after it had been shattered by flak and the power to turn it in position for me to fall backward had been cut off. I was forced to break my way out although I was wounded and hit in several places...I crawled to the nose wheel area, snapped on my chest chute, and because my legs were useless, crawled through the tunnel under the flight deck to the bomb bay catwalk. The only men I saw on board at that time on the flight deck were Col. Vance and the dead pilot, Captain Mazure."

The chronology of events and the accounts of the individual members of the crew that flew Missouri Sue to Wimereaux on the day before D-Day sometimes appear confusing and contradictory. Such is to be expected when twelve men endure such extreme trauma in so short a time. Sergeant Hoppie recalled looking at his watch as he touched down from his parachute drop. The time was 10:02 a.m. From takeoff through the determined effort to successfully bomb the target, followed by the desperate challenges to get home safely, only 62 minutes had passed.

The facts of the mission are these:

1. When Missouri Sue's bombs failed to release on the first run over the target, Lieutenant Colonel Vance ordered a 360-degree turn for a second pass.

2. Somewhere in the process of the second bomb run Missouri Sue was repeatedly hit by flak, killing the pilot, wounding several members of the crew, and nearly severing Vance's right foot.

3. Three of the bomber's engines were destroyed and the fourth had to be shut down to prevent a stall. Damage throughout caused a shower of gasoline, and throughout the trip home the bomb bay doors remained open with an armed 500-pound bomb dangling precariously therefrom.

4. Through a valiant team effort under the leadership of Vance and with the deft skills of co-pilot Rocket Carper, the B-24 reached the coast of England, enabling ten men to successfully parachute to safety.

5. By 10:05 a.m. the powerless Missouri Sue was still gliding ever downward along the English coastline at about 10,000 feet. Only the dead pilot and seriously wounded command pilot remained inside her.

Lieutenant Bail's reference to Vance suffering from shock aside, the Command Pilot later gave two additional reasons for his decision not to parachute from the falling bomber. In a subsequent BBC Radio interview, Vance recalled the earlier interphone message that Sergeant Skufca had been wounded in the legs and said, "I found out that Sgt. Skufca was in the waist area and badly injured, and couldn't bail out. So, naturally, I couldn't leave him." At that time Vance had no way of knowing that the tail gunner had dragged the unconscious radioman to the bomb bay and helped him out, or that Skufca had revived during his fall.

"All of the rest did bail out and I flew the ship down to crash-land in the Channel," Vance continued in the radio broadcast. "The windshield was cloudy with vapor and foggy, so that you could hardly see through it. I was lying on my stomach between the pilot and co-pilot seats with my hands on the wheel. I tried to get up but my foot was lodged around the flight deck. I could not take my hands off the controls to get my leg loose, as the plane would have stalled. It was hard to hold the ship level because the right elevator was shot away."

Beyond the fact that Vance was still trapped in the cockpit with his nearly severed foot wedged so tightly he could not maneuver, and beyond his concern for what he thought was a wounded airman unable to parachute to safety, there may have been a third reason for his valiant efforts. Vance himself never spoke of it, but it was widely reported in subsequent news and other reports.

Missouri Sue remained a serious threat as long as it was over England. Had the bomber fallen into a populated area the combination of the bomb still hanging from the open bomb bay doors and the fuel-soaked fuselage, and an awful explosion might have killed hundreds of people on the ground. In fact, following the sight of ten parachutes falling from the bomber, indicating what would normally have been the FULL crew of a returning B-24, there was every reason to believe Missouri Sue was a pilot-less missile of dangerous proportions.

Years later Lieutenant Glickman attended a reunion of members of the Second Air Division at the U.S. Air Force Academy where he met the pilot of one of the returning, undamaged aircraft. "He had witnessed the damage to our plane and had counted the number of our crew that had bailed out," Glickman related. "Our plane was still airborne and headed inland, but as you know, was losing altitude. Someone had contacted the authorities, which, in turn, were concerned that the plane might crash into a built-up area and allegedly, gave orders to them to shoot it down. Just as they turned to follow those instructions, our plane began its very slow turn to the left back towards the Channel where both Segal and I bailed out. The order, of course, was canceled, when it was noted that the plane was still under control and attempting to turn."

Just how Lieutenant Colonel Vance continued to control Missouri Sue at that point defies belief. His trapped foot had been stretched out nearly twelve inches from the leg, still hanging on to the tough sinews of the Achilles tendon. Somehow Vance had to glide the bomber away from land, yet put her down in water shallow enough for him to free himself and reach and rescue the wounded man he believed was still in the waist.

"I had been scared on my first mission and I was scared on this one," Vance recalled for an article in True magazine. "Some people say they get scared before the take-off and forget about it when they get in the air. Some say they don't get scared until it's all over. Well, I was scared all the time."

"I began to get furious at the ice on the windows. Once or twice I lifted my right hand and tried to hit them. Then it struck me that I was acting like a little boy--like a youngster who hits the table because he has bumped his head."

"For some reason or other, this struck me as highly amusing and I began to laugh. It was hysterical laughter, I suppose, but I think it helped clear my head. There was no definite pattern to my thoughts, but they were reasonably clear."

"Things came flooding into my brain. All sorts of things. My daughter Sharon--she's about two--laughing as she had laughed one day back home. My wife. Small things we had done together. Things that didn't mean much at the time came back to me--clear and vivid."

"And then I would try to calculate my landing speed. Three hundred, I'd say, 'Hell, no, one hundred and sixty. Don't forget this is a Liberator, not a fighter.' And then I'd get mad as the devil at myself again for being so stupid. That's the way my thoughts were--mixed up, but clear and sharp."

"Deep down, I really believe I knew I was gone. I think if I had been alone--if I hadn't thought there was another man somewhere in the ship--I might have given up and just let things go. I'm not sure of that, of course, but I do think that fighting for two instead of one might have helped a little."

Stretched out nearly prostrate between the pilot and co-pilot seats, Vance strained against the tendons that still trapped him to control Missouri Sue as it dropped towards the water. Ignoring horrible pain and fighting back nearly uncontrollable fear, he operated the controls while fighting for any angle that would allow him to peer out the one small, open window to judge the moment of impact. As the waves grew closer, he pulled his parachute pack over his head "so that I would not break my neck with the shock of impact." Moments later the bomber hit hard, the nose slamming into the crest of a wave.

"When the ship hit the water, the top turret came off, pinning me down," Vance recalled. "I was lying on my back and I was under about six feet of water. I figured that was the end of the line for me."

"That (being pinned down) was the worst part of the whole thing. I was certain that I was gone. But I was honestly past the point of being frightened. I just felt sad--horribly sad--sad as hell."

"Then I did something rather odd. I knew pilot Mazure was dead, but I reached over with my left and released his safety belt and pulled him up over my head toward the escape hatch. My lungs were hot and bursting and I know I must have been near the very end when it happened. I still don't know what it was. It couldn't have been the five-hundred pounder still in the bomb bay, because that would have blown me to bits. It might have been one of the small oxygen bottles."

"At any rate, something exploded and I found myself again in the outside world with the sun shining down in my face. I remember the disbelief in the whole few seconds. I absolutely couldn't believe that I was still alive. I thought that this must be a part of death. There was nothing in sight. The water was very calm and there was a slight ground haze over everything."

"After I got out, I tried to climb back over the top of the ship to get Sgt. Skufca, the injured radio operator, but I just didn't have the strength. But it was just as well because, unbeknown to me, the two waist gunners had bailed him out."

"The only thing that connected me with the living world was the sun, shining hot through that haze. I knew there was something I should do, but I couldn't think what it was. I began swimming. Nothing happened when I kicked my right foot and I realized then for the first time that there was something wrong with it."

"I saw an oxygen bottle floating near me and tried to climb up on it. Did you ever try to get on one of those rubber horses in the water? That was the way this was. I kept slipping and falling off, getting weaker and weaker. I think I had some kind of an idea of tying myself to it, because I was afraid now that I would lose consciousness and roll over on my face."

To maintain consciousness Vance stared into the sun and, every time he felt his mind starting to blur, kicked himself with his one good leg or punched himself to inflict enough pain to keep him cognizant. An official Army press release issued four days later noted, "In a test of physical stamina that defies explanation the one-legged man swam for three miles in the icy water for forty-five minutes before he was picked up by a rescue (sic) ship." Quickly but carefully the British crew of the launch pulled the barely-conscious American officer from the water, his right foot still dangling on its tendons. Vance managed a quick smile and joked, "Don't forget to bring my foot in."

Then he mercifully passed out.

June 6, 1944

Five minutes into the new day, July 6, 1944, D-Day began to unfold when three gliders carrying soldiers of the British 6th Airborne Division landed near the Pegasus Bridge over the Seine River. By 2 a.m. additional gliders carrying American paratroopers of the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions began landing across occupied France. Meanwhile, some 5,000 ships negotiated the still-rough waters of the English Channel to carry the first of 3 million soldiers to the enemy shoreline in Operation Neptune.

Operation Overlord, what was then and what remains today as the largest amphibious invasion in world history, had at last begun.

Preceded by more than an hour of intense naval bombardment on enemy shore emplacements, the first Allied soldiers waded ashore at Utah Beach at 0630. Five minutes later the landings began at Omaha Beach, led by the 116th Infantry Regiment, composed largely of National Guardsmen from Bedford, Virginia. The regiment suffered nearly 99% casualties in fifteen minutes, but the stream of determined young men of the 1st Infantry Division continued to assault Omaha Beach to reach their objectives.

Preceded by more than an hour of intense naval bombardment on enemy shore emplacements, the first Allied soldiers waded ashore at Utah Beach at 0630. Five minutes later the landings began at Omaha Beach, led by the 116th Infantry Regiment, composed largely of National Guardsmen from Bedford, Virginia. The regiment suffered nearly 99% casualties in fifteen minutes, but the stream of determined young men of the 1st Infantry Division continued to assault Omaha Beach to reach their objectives.

Further east British and Canadian forces made similar landings at Gold, Juno, and Sword. In all, the long-anticipated invasion involved the cooperative efforts of a dozen Allied nations: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The great success of the dangerous gamble that was D-Day was only possible because of the great cooperation of all involved. The same could be said for the various branches of military service.

The Normandy Invasion was the greatest example of multi-branch cooperation in our Nation's history of warfare. Covert activities by OSS agents employed by Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and airmen paved the way. Naval PT Boats made daring night-time, pre-invasion landings on the beaches to determine landing conditions. When the mission unfolded the crossing employed servicemen and servicewomen of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Merchant Marines, and Army Air Force. Storming ashore in the pre-dawn raid were Army Infantrymen, Navy Seabees, Coast Guard landing craft operators, Artillerymen, Armor, as well as clerks, truck drivers, cooks, medical personnel, chaplains--and more. The D-Day effort drew its success from the great sense of cooperation of everyone involved.

The opening day of Operation Overlord placed great demands on airmen of the 8th and 9th Air Forces in efforts to fulfill their own areas of responsibility. In support of Neptune, more than 1,400 C-47s and C-53s from the 9th Air Force delivered gliders, troops, and paratroopers into the combat theater. In support of Overlord, more than 800 A-20 and B-26 bombers attacked German defensive batteries in and around the landing sites. Some 2,000 fighters were employed flying escorts for bombing missions as well as sweeps and dive-bombing raids on enemy ground installations, troop movements, and other targets throughout France. Considering the high number of aircraft employed, the 30 American airplanes the 9th Air Force lost represented a strikingly low casualty rate.

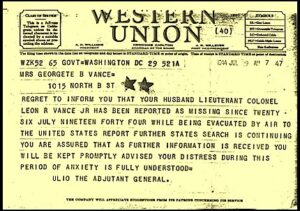

The Mighty Eighth mounted four bombing missions on June 6, including an early morning attack when more than 1,000 heavy bombers attacked enemy beach installations, while 47 attacked transportation checkpoints in Caen. The second mission sent more than 500 bombers to attack transportation points around the landing site to inhibit the enemy's ability to reinforce their defensive positions at Normandy. Many of the third waves were unable to bomb targets because of the cloud cover, but 553 heavies returned to bomb through the overcast in the day's fourth bombing raid, demolishing much of the German communication center at Caen. In all, on D-Day, the Eighth Air Force dispatched 1,729 heavy bombers to unleash 3,596 tons of ordnance. Only three bombers were lost, one to ground fire and two in a mid-air collision.