Neel E. Kearby

Fire & Ice: Race to Become First Top-Gun

C. Douglas Sterner

It was late June 1943, and a lone American P-38 Lightning circled leisurely over Amberley Field near Townsville, Australia. In the cockpit was Lieutenant Colonel George Prentice, a solid combat veteran with two aerial victories, including one shoot-down four months earlier during the critical Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

Lieutenant Colonel Prentice had arrived from New Guinea the previous day where he had flown regular and highly dangerous air missions for nearly a year. At Amberley Field, he was now to assume command of the new 475th Fighter Group. Organized on May 15, it was to be the first Fifth Air Force All-P-38 fighter squadron. In the preceding year, the P-38 had proven itself superior in combat, not so much for its sleek design and great maneuverability, which were indeed valuable assets, as for the daring prowess of the young men who flew them.

The night before there had been a celebration of sorts to welcome the new commander, and Colonel Prentice had celebrated in style with his men. A little hung-over the morning after, as he circled Amberley Field in the clear, early morning skies, the veteran pilot knew he was not at the top of his game. Nonetheless, with a keen eye and a sense of duty borne out of his combat experience, Prentice felt confident that he would rise to any challenge. Besides, Amberley Field was 600 miles from New Guinea, where little remained of the once invincible Japanese air force.

On the ground, scores of American airmen watched the sleek frame of the distinctive twin-engine, twin-tailed, American combat plane as it flew an erratic but confident patrol over Amberley Field. All of them knew that a battle was brewing; few of them believed that the experienced Lieutenant Colonel Prentice would have anything to fear. For the moment the American fighter pilot was alone, commanding the air space from an altitude of 12,000 feet where very little could harm him.

Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a second fighter appeared. Incredibly, the invader was diving from above… instantly and with deadly precision, in a lethal attack on Colonel Prentice’s P-38. Powered by a single, 2,400-horsepower radial engine and with the added inertia of a seven-ton monster of a fighter plane, the attacker screamed in for the kill at more than 400 miles per hour. Four large machine guns were mounted on each wing, every one of them ready to fill the doomed P-38 with hundreds of 50-caliber rounds in less than a minute. Looking out his cockpit window, Lieutenant Colonel Prentice cursed his over-confidence, winged over, and tried to shake the barrel-shaped behemoth off his tail. It was too late – the attacking enemy couldn’t be shaken. Lieutenant Colonel Prentice, flying his first mission as commander of the 475th Fighter Group, knew he was dead.

Twenty minutes later the victorious enemy fighter plane taxied to a stop on the ground at Amberley Field. The canopy opened and the smiling pilot emerged wearing the uniform of an American airman, with the silver leaf of a Lieutenant Colonel. Neel Kearby hopped down from the wing of his new P-47 Thunderbolt to exchange handshakes with a slightly-humbled P-38 group commander.

“Congratulations Kearby,” Colonel Prentice announced good naturedly. “You shot me down in flames more than once.” Then, looking around at the group of fellow pilots who had witnessed the mock-combat over Amberley he announced, “I still think the P-38 is the best fighter we’ve got, but boys, don’t sell the ‘Jug’ short!”

Perhaps at that moment, the only person happier to hear those words than Neel Kearby was the two officers’ boss, General George Kenney. But the Fifth Air Force commander had little time to gloat in his success before he heard Prentice announce, “I think I’ll hit the sack early tonight and get some rest. Neel, what do you say we have another go at it tomorrow.”

“I interfered at this point,” Kenney wrote later, “and said I didn’t want any more of this challenge foolishness by them or anyone else and for both of them to quit that stuff and tend to their jobs of getting a couple of new (fighter) groups into the war.”

No doubt Prentice was disappointed that he would not get a chance to avenge his loss, but he and his boys would have many a re-match with Japanese Zeroes during which they would further validate the combat prowess of the Lightening. Kearby accepted the prohibition against additional mock-combat gracefully, knowing that at last, he had earned a measure of respect for his own favored P-47 Thunderbolts. Now it was time to teach that same measure of respect to the Japanese.

Both commanders parted amicably and with broad smiles. Of the two, only Lieutenant Colonel Kearby knew that the entire exhibition had, in fact, been the brainchild of General Kenney himself and that the Fifth Air Force commander had done his best to ensure the desired outcome.

Neel E. Kearby

Probably the only thing about Neel Kearby that didn’t shout the name “Texan” was his stature. Unlike the stereotype: tall, rugged, fearless, and filled with attitude–Neel stood only 5’9″ tall. The rest of him more than adequately fit the mold.

Born in the rural North Texas town of Wichita Falls along the Oklahoma border in 1911, Neel was the son of Dr. and Mrs. J. G. Kearby of Dallas. He grew up in Arlington, a thriving metropolis sandwiched between Dallas and Fort Worth, where he first attended high school and later North Texas Agricultural College, before transferring to the University of Texas at Austin. He graduated there in 1937 with a degree in Business Administration.

As a boy, Kearby had always been fascinated with aviation. He earned his first flight by agreeing to wash a neighbor’s private plane. But Kearby’s interest was not only in flight but in aerial combat. His boyhood heroes were the pilots of the last great war, the aces of World War I. He compiled a personal collection of albums featuring the great aviators who had inaugurated aerial warfare and dreamed of someday being like them. Such dreams compelled him to enlist as a flying cadet after earning his degree, and he received his commission as an Army Air Corps aviator in February 1938.

Neel Kearby was an easily likable man, reserved on the ground but a tiger in the air. From his early days of learning to fly in aged AT-6 Army trainers in Texas in 1937, to his tour of duty flying P-39s in Panama during the first year of World War II, Neel Kearby was known to take his flying seriously–and competitively. In the cockpit, he was a skilled airman, cool under pressure, and driven to excel. He was also a keen tactician and a natural leader. By the time Kearby received orders to depart Panama and assume command of the new 348th Fighter Group at Westover Field, Massachusetts, in October 1942, he had risen to the rank of Major in fewer than four years.

P-47 Thunderbolts

Under Major Kearby, the 348th Fighter Group began training for combat, equipped with the newest advancement in fighter aircraft, the P-47. Built by Seversky Aircraft Corporation (later renamed Republic Aviation), the Thunderbolt was designed specifically for the air war in Europe as an escort fighter for high-altitude bombers. For this reason, maneuverability was sacrificed for greater fire-power, heavier armor, greater durability, and a larger engine. The end result was a nearly 7-ton fighter framed within a bulky, barrel-shaped fuselage. The ungainly airplane was quickly renamed the “Jug” in derision by other pilots who saw it as ugly and unsuitable for combat. To make matters worse, the heavy fighter was very slow taking off and had a very poor rate of climb. Other pilots joked that if Army engineers built a runway all the way around the planet, “Republic (Aviation) would build an airplane that needed every foot of it (to get airborne.”)

Neel Kearby the tactician looked beyond the engineering nightmare that was the P-47 and found a flying arsenal. Featuring eight, forward-firing, heavy 50-caliber machineguns, the Thunderbolt was a flying warhead that could dive with impunity into the most fearsome enemy formation and emerge unscathed. The P-47 was designed to withstand a six-ton impact, making it virtually indestructible. Kearby continued to acquaint himself with the capabilities of the Thunderbolt and to train his pilots to take advantage of the aircraft’s natural abilities for the high-altitude air war over Germany. By May his men were ready for combat in Europe.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, General Kenney’s P-38 pilots had been writing an impressive resume for their fast, highly maneuverable Lockheed Lightnings. Outnumbered more than two-to-one by the Japanese less than a year earlier, and supplemented primarily by aging and battle-damaged P-39s and P-40s, Kenney’s fighter pilots now ruled the skies over eastern New Guinea.

• “A” for Attack (Diver Bombers)

• “O” for Observation Airplanes

• “C” for Cargo Airplanes • “G” for Gliders

• “CG” for Cargo Gliders

• “AT”, “BT”, “PT” for Trainers

The Fifth Air Force had played a key role in the highly successful campaign to secure the north side of the Papuan Peninsula and establish air bases east of Lae, then had crushed the Japanese effort to reinforce Lae during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. Kenney’s Fifth Fighter Command was victorious but badly bruised. In March 1943 General Kenney made his first visit to Washington, D.C., since taking command of the Fifth Air Force less than a year earlier. A key part of this trip, beyond briefing Hap Arnold and the General Staff on the progress in the Pacific, was to plead for replacement pilots and new aircraft. The Fifth Air Force had accomplished what a year earlier was considered impossible, but the toll left the command worn, torn, bleeding, and struggling to keep airplanes in the air. The combat toll had been so extensive it was not unusual for more than half of the aircraft-mounted for a mission to be forced to abort, not because of enemy fire, but because of mechanical failure.

Kenney quickly learned that among the top Allied war planners, despite his tremendous success in the Southwest Pacific, defeating the Japanese was a “war on the back burner.” Most Allied efforts were focused on defeating the Axis in Europe. This was not a message Kenney wanted to hear or a decision he would accept. He continued to plead for new pilots and aircraft, and the effort finally paid off. On March 22, less than ten days before Kenney’s return to Port Moresby, Hap Arnold called him to his office. He advised the Fifth Air Force commander that he had “squeezed everything dry to give him some help.” That help was to come in the form of:

• One new heavy bombardment group

• Two and a half medium bombardment groups

• Three new fighter groups–and, “Oh, one of those groups will have to be a P-47 group. No one else wants them.”

Desperate for anything, despite all the negatives he had heard about the P-47, and ignoring his own misgivings about the ungainly Jugs, Kenney said he would gladly take anything Hap chose to send.

Major Kearby took a badly needed break from making his squadrons ready for combat in Europe on April 3, two days after George Kenney left Washington to return to his own command. That seven-day leave gave Kearby the opportunity to spend a little time with his children and his beautiful wife Virginia, whom he affectionately called “Ginger.” When he returned to work on April 9, it was to find something unusual going on. The 348th Fighter Group was being readied for deployment.

Within 30 days the group moved to Camp Shanks, New York, to begin their final preparations before leaving for overseas combat. On May 14 both pilots and planes were boarded on the Army Transport Henry Gibbons. On May 21 the Henry Gibbons passed through the Panama Canal, and the men aboard who were headed for war, at last, knew what many had begun to suspect, that the 348th Fighter Group with its P-47 Thunderbolts was not headed for Europe. They were, in fact, the group no one else wanted that Hap Arnold had promised General Kenney.

The 348th Fighter Group was headed for war in the Pacific with their unwanted, untested, and oft-derided, P-47s Thunderbolts.

Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby reported for duty with the Fifth Air Force at Brisbane, Australia, on June 20. Meanwhile, his ground crews and crated P-47s continued on to their final destination further north at Townsville. General Kenney recalled meeting Kearby for the first time quite well. The newly-arrived group commander made a solid impression, not only for his resume as a seasoned pilot with 2,000 hours of flight time already on the books, but for his eagerness for combat. From the moment of that first meeting, something clicked between the two men, and they became very close friends.

Neel Kearby’s boyhood heroes had been the great aces of World War I, men who admired and hoped to emulate. Perhaps Kenney saw in Kearby the same fire, ability, and hunger that had marked one of those men, the pilot even Eddie Rickenbacker had proclaimed the “the greatest airman of World War I,” the unstoppable Frank Luke. Kenney had flown combat in that earlier war, shooting down his first German plane on the same day Luke began his incredible string of aerial victories by bagging three balloons in a day on September 15, 1918. Kenney knew well the story of Luke’s competitive personality, his daring braggadocio, and the skill as a pilot that had enabled him to accomplish what he proclaimed he would do. (In all, Kenney netted two confirmed kills in World War I, earning the Distinguished Service Cross for his second aerial victory on October 9.)

Kenney wrote of that introduction:

“Kearby, a short, slight, keen-eyed, black-haired Texan about thirty-two, looked like money in the bank to me. About two minutes after he had introduced himself he wanted to know who had the highest scores for shooting down Jap aircraft. You felt that he just wanted to know who he had to beat.”

In the summer of 1943, General Kenney had plenty of seasoned heroes under his command of whom he could be…and was…justifiably proud. There was Captain George Welch who had shot down four Japanese airplanes at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, earning him the Distinguished Service Cross. Still knocking down enemy airplanes, Welch scored his ninth victory the day after Kearby reported.

Captain Tom Lynch and First Lieutenant Richard Bong were tied at eleven victories each and looked to be poised for many, many more. The previous December, Eddie Rickenbacker himself had visited the Fifth Air Force, promising to match Kenney’s proffered case of Scotch to the first airman to beat the World War I Ace of Aces’ unequaled twenty-six aerial victories. Kenney had no doubt that one of his young pilots would eventually reach that benchmark, and any one of his three veteran aces was capable. But Kenney recognized a difference in the attitude of the young Lieutenant Colonel before him, who had reported for duty by inquiring who he had to beat for the top spot on the victory list.

Though Welch, Lynch, and Bong were each capable of breaking Rickenbacker’s record, none of the three felt pressured to do so. For them, aerial combat was a daily job of shooting down enemy planes. Theirs’ was not a race to the top. They were simply doing a job to be done, and they were all three very good at doing their jobs. Neel Kearby, on the other hand, had a hunger in his eyes. It was a drive perhaps fueled by his boyhood adoration of the World War I top guns, coupled with the boyhood dream to emulate, and even exceed, the accomplishments of his personal heroes. Beyond the hunger that fueled his intensely competitive spirit, Lieutenant Neel Kearby had both the skill and tactical prowess to accomplish his goals. Perhaps the only real difference between Neel Kearby and the great balloon-buster Frank Luke was that, while Luke’s braggadocio turned off his fellow pilots and relegated him to being a lone-wolf, Kearby was an easily likable man. No one, least of all General Kenney, took offense when the 348th Group commander began to proclaim that he intended to shoot down fifty Jap planes.

Of course, before Kenney’s newest would-be ace could get started, General Kenney had to get him into combat. That, despite Kearby’s eagerness, was no small matter. First and foremost, it would take a month to assemble the crated P-47s at Townsville. Once assembled, the small fuel tanks would limit the range of combat operations, necessitating additional delays until supplemental “wing tanks” could be manufactured and installed. To further complicate matters, the veteran pilots of the Fifth Fighter Command weren’t all that confident that the P-47 Thunderbolts were even capable of combat operations.

“I told Kearby that, regardless of the fact that everyone in the theater was sold on the P-38, if the P-47 could demonstrate just once that it could perform comparably I believed that the ‘Jug,’ as the kids called it, would be looked upon with more favor.

I told him that Lieutenant Colonel George Prentice would arrive that afternoon from New Guinea to take command of the new P-38 group which I had formed and had started training at our Amberley Field. He would probably celebrate a little tonight. I told Neel to keep away from Prentice, go to bed early, and the first thing in the morning to hop over to Amberley in his P-47 and challenge Prentice to a mock combat. Neel Kearby was not only a good pilot but he had several hundred hours’ playing time with a P-47 and could do better with it than anyone else. Prentice was an excellent P-38 pilot, but for the sake of my sales argument I hoped he wouldn’t be feeling in tiptop form when he accepted Neel’s challenge.

General George C. Kenney

General Kenney Reports

It was this critical situation that led to the early morning of mock-combat over Amberley where General Kenney’s gamble paid off, resulting in Kearby shooting down Prentice’s P-38 several times. Kenney, for his own part, was pleased with the outcome and quick to nix any hopes for a rematch. The single clash between P-38 and P-47 had achieved its necessary goal. In a rematch, with Prentice at the top of his form, the results might be reversed.

For the moment it was sufficient to know that at last the Thunderbolts had been accepted, even if still dubiously so, as a part of the combat inventory of the Fifth Air Force. The real test would come later when they faced the Japanese in the air. Kenney could only hope that the P-47 would again prove itself a capable fighter, despite its many deficiencies.

During the last week of July, Lieutenant Colonel Kearby began moving his fighter squadron to Port Moresby. Even as they were arriving, Kearby’s competition was growing. On July 26 Lieutenant Bong had his single-best day of the war, shooting down four enemy planes and earning the Distinguished Service Cross. Two days later he bagged another, bringing his score to sixteen.

If Dick Bong wasn’t counting, Neel Kearby certainly was. He saw his competition increase at the same time he and his men were relegated to generally uneventful duty at Port Moresby, missions that offered little chance for combat. Kearby’s P-47s were still on a short leash for lack of supplementary wing tanks. Besides that fact, the slow-to-takeoff Jugs made them well-suited to the defense of Port Moresby. Radar provided up to an hour of advance warning before incoming bogies arrived and, even at their slow climb speed, an hour was ample to get the Thunderbolts in position to meet an incoming Zero or bomber.

During the first two weeks of August, the Japanese began reinforcing New Guinea by moving hundreds of fighters into airfields west Lae, on the north coast of the island, in and around Wewak. Kenney responded at mid-month with the most sweeping raids since the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. It was during these missions on August 18 that Major Ralph Cheli was shot down while piloting his B-25, earning him a posthumous Medal of Honor.

That same day, a new would-be top gun with a fire akin that which burned within Neel Kearby got his first, and second…and the third victory. Two days later the newly arrived Tommy McGuire became an ace in his P-38.

Dick Bong missed the action around Wewak in mid-August when the Fifth Fighter Command had some of its best hunting. The leading Army ace in the Southwest Pacific had suffered battle damage in a July 28 mission, and his plane was out for repairs. Kenney promoted Bong to Captain and sent him to Australia for R & R while his P-38 was being repaired. In Bong’s absence, Tom Lynch took up the slack, shooting down two enemies on August 20 and bringing his own total to fourteen. He scored another victory the following day.

While Kenney’s Lightning’s had a “field day” in the skies over the Huon Gulf and around the airfields near Wewak in the latter weeks of August, Kearby’s Thunderbolts continued to fly nondescript missions–protection patrols at Port Moresby and Dobodura, and routine convoy escort operations. The one-piece of good news in the month came on August 16 when sixteen P-47s flying close escort duty for Army transports bound for Marilinan were attacked by a dozen enemy Oscars. Captain Max Wiecks and Lieutenant Leonard Leighton each scored a victory, the first for the 348th Fighter Group.

Lieutenant Leighton was himself shot down and was last seen parachuting into the jungle below. Several months later an Allied patrol found his body, confirming him as the Group’s first combat casualty.

When the month of August ended, Dick Bong was in Australia, Tom Lynch was two victories behind Bong with fourteen kills, and the rookie Tommy McGuire’s tally was up to seven. Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby, who had yet to prove the true value of his P-47s despite the Groups two victories, was still fifty victories shy of the mark he had set for himself. And for the most part, Kearby and his pilots were still stuck in convoy escort duty, far from the fertile hunting grounds around Wewak.

September 4, 1943

First Blood

After the fall of Buna and Gona in January, Allied attention focused on routing the last Japanese stronghold at Lae, near the Huon Gulf. Early in the Spring General Kenney established an airfield at Tsili Tsili, just forty miles from the large and critical port of Lae. Then, on September 3, he dispatched twenty-three heavy bombers to unload 84 tons of bombs on Lae’s gun defenses while nine strafers followed with more than 500 fragmentation bombs and 35,00 rounds of machine-gun fire. It was preparation for the final showdown to at last capture Lae.

The following morning two dozen B-24s dropped another 96 tons of bombs on Lae. Meanwhile, Major General Wooten’s 9th Australian Division, departing out of Buna, landed in U.S. Navy LSTs on Hopoi Beach a short distance east of Lae. The invasion date had been selected based on suitable weather, cloud cover, and fog to keep enemy planes based on nearby New Britain Island from interfering with the landing. Unfortunately, that same weather masked events on the surface of the ocean from the fighter cover flying just above the haze. When the transports neared the beach, enemy shore batteries opened up with a withering fire. Simultaneously, enemy airplanes hidden in the nearby jungle managed to slip in beneath the haze to attack the landing force.

LST 473 was approaching the beach with its cargo of Australian infantrymen, tanks, and supplies even as a torrent of deadly shells erupted in the waters around it. The transport continued its course towards the beach, determined to brave the maelstrom. Suddenly one of the Japanese dive bombers came in low and released a torpedo directly into the path of the landing craft. Seaman First Class Johnnie David Hutchins glanced quickly to the pilothouse to warn the steersman when, in an instant, a bomb-shattered LST 473. The explosion killed the steersman and mortally wounded Seaman Hutchins, leaving the barge nearly dead in the water. LST 473 was helpless and the ship and the men it carried were doomed by the incoming torpedo.

With only seconds to react, and with the last vestiges of life vanishing from his battered body, somehow Johnnie Hutchins managed to stagger to the wheel and turn the ship clear of the torpedo’s path. Then he died, still clinging to the wheel.

Around him combat-hardened Australian soldiers who had seen the act were awed by the sheer resolve and determination they had witnessed. They could not forget the smiling, blond, 21-year-old sailor from Texas who had sacrificed his last ounce of ebbing strength to save their lives. One year later at the Sam Houston Coliseum in Houston, Texas, Rear Admiral A. C. Bennett presented Johnnie Hutchin’s well-deserved Medal of Honor to his mother.

Despite the hail of enemy fire from the beach, General Wooten’s Rats of Tobruk, so-named for their own heroic stand a few years earlier in North Africa, landed together with their tanks and supplies. Before noon the transport convoy began the return trip to Buna, save for Johnnie Hutchins’ and one other transport so damaged that it would only get as far as the port at Morobe.

The returning convoy was faced with new dangers when the afternoon sun burned off the haze, exposing the ships to enemy flights out of New Britain. At the airfield at Dobodura near Buna, Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby was unaware that enemy pilots had killed a fellow Texan, but he was well aware that a fight was brewing. Word reached Dobodura that enemy aircraft had been sighted moving into the Morobe, Salamaua, and Finchhafen areas, which were near the invasion site at Hopoi Beach. It was the anticipated enemy response to the landing of Australian troops on the doorstep of their fortress at Lae.

Kearby’s Thunderbolts began taking off around two o’clock in the afternoon, Yellow Flight from the 342d Squadron, followed by seven more airplanes of Blue and Green Flights. The last flight of twenty P-47s was led by the Group commander himself.

Half-an-hour later Kearby’s formation of four fighters were fourteen miles south of Hopoi Beach, cruising easily at 25,000 feet, when Neel saw what appeared to be two fighters and a flying boat flying close-formation miles below. At that distance it was impossible to identify the bogeys and Kearby knew if he dove, he would lose precious altitude that would be difficult to recover if the dark blips beyond turned out to be American. Kearby noted the signs of bomber damage around Morobe and several fires in the water near Cape Ward Hunt, and decided the possibility that the unidentified airplanes were enemy made it worth the risk. With his wingman trailing, he nosed into a steep dive at more than 400 miles per hour, closing the gap in less than a minute.

At 2,000 feet Kearby and Lieutenant George Orr, his wingman, closed to within three-hundred yards behind and to the left of the three aircraft. The large flying boat in the center was a Betty bomber, protected by a Zero and an Oscar close on each wing. The red orbs of the rising sun confirmed their identity as Japanese.

Adrenaline filled every fiber of the would-be super-ace at the prospect of his first combat. Perhaps it was buck fever, it was doubtless not by design, that rather than making a nearly sure-shot at one plane, Neel Kearby unleashing his eight 50-caliber machineguns on two enemy at once. Even before Lieutenant Orr could trigger his own guns, the wingman watched in amazement as the Betty bomber exploded. One wing ripped away from one of the escorting fighters, causing it to also plunge into the sea below. Kearby knew he had been lucky–his first victory had been a double-punch. Chalk one up for the highly touted increased firepower of the P-47. There could be no more doubts.

The P-47s zipped past the flaming, falling debris that had been two enemy planes before they could sight on the third fighter. Struggling against the inertia of their diving seven-ton Thunderbolts, Kearby and Orr banked and tried to pursue the now vanishing Oscar. Kearby tried to line up for a third kill, but the Japanese pilot executed a nimble climb, leaving Kearby’s sights filled only with blue sky and white clouds.

Nearly thirty enemy aircraft were destroyed on September 4, six by the anti-aircraft guns in the convoy, twenty-one of them by General Kenney’s P-38s. Neel Kearby scored the only victories for the 348th squadron. Kearby also realized that his over-eagerness had disrupted what could have been a near-perfect attack, one that would have netted all three enemy planes.

The keen tactician mentally noted his mistakes, which could not take away from his celebratory mood upon returning to Ward’s Drome. Not only was he at last in the race for Top Gun, he had demonstrated the soundness of a tactic he had preached to his pilots since they received the first P-47s back in the states. Despite its weight, its clumsiness at low altitudes, and its slow rate of climb, the Thunderbolt could be deadly when tactically deployed. Kearby would leave it to lighter, more nimble fighters to dog-fight at low altitudes. Proper use of the Thunderbolt meant free-roving flights at high altitude, where they were designed to fly, and where they could track enemy formations unseen. When the moment came for combat the Thunderbolt’s unequalled diving speed would put its guns within range of destroying that formation, long before the enemy even knew American pilots had spotted them.

The battle for Lae was the focus of the Fifth Air Force efforts for nearly two weeks. On September 5 Kenney’s bombers continued to pound enemy positions in support of the ground operations. This further including dropping Australian paratroopers into Nadzab west of Lae. For the Australians, it was their first jump ever. After a last-minute decision to insert them by air, their pre-jump training had consisted of nothing more than brief instructions on how to pull the ripcord that deployed the chutes. The operation was surprisingly successful and by nightfall Nadzab was in Allied hands.

The following day air operations continued with Fifth Air Force C-47 transports flying General Vasey’s 7th Australian Division into Nadzab. To protect the troop movement, bombers continued to pound enemy fortifications around Lae, and fighters did their best to keep enemy aircraft out of the battle. Dick Bong, recently returned from Australia, claimed two more enemy aircraft shot down. Neither was ever confirmed or added to his score–which is ironic. If Dick Bong claimed he shot something down, it was no exaggeration. The intrepid Captain had a reputation, not of padding his score, but of frequently giving credit for his own victories to other pilots. Unfortunately, on returning to Marilinan airfield, Bong made a difficult crash landing. Though he survived uninjured, he was again temporarily out of action.

The ground combat to take Lae continued unabated and with great success by the determined Australians in the week following the landings at Hopoi Beach and Nadzab. Air operations, on the other hand, were greatly hampered by a week of poor weather. Towards mid-month the weather began to clear slightly, and increased air combat followed. Neel Kearby’s double victory on September 4 brought to four the total number of aerial victories for his fighter group. On September 13 Major Bill Banks and Lieutenant Larry O’Neill each scored while flying routine transport cover, upping the P-47 tally to six.

The following day, while leading a similar mission at 20,000 feet near Nadzab, an unidentified aircraft was spotted about 9:45 a.m. above and to the right of Kearby’s formation. When the bogey saw the American planes it began a desperate race for the clouds, a quick indication to Kearby that it was enemy.

Kearby’s P-47s were now operating with disposable drop tanks to extend their range. These supplemental fuel cells were normally released only before combat, at which time they were lost forever. Realizing he was still short of drop tanks, Kearby ordered his other pilots not to drop their tanks. Instead, he would drop his own and pursue the enemy alone. It was too late. With an eagerness for combat that Kearby could now identify with, six of his seven pilots had already dropped their tanks to follow their commander into combat. (Kearby later learned that the seventh pilot would have dropped his as well, but the mechanism jammed.)

Kearby got there first, closing in at three-hundred yards on what he could now identify as a Japanese Dinah. A single, three-second burst from eight machineguns sent the enemy plane down in flames, and Kearby had upped his score to three. It would be his last for the month, indeed the last for a dry spell lasting nearly 30 days. Meanwhile, in that first full month of combat, his Thunderbolt fighter group had claimed eleven confirmed victories, at least another dozen probable but unconfirmed, and with the loss of only two of their own.

On the day Neel Kearby got his third victory, Tom Lynch became a triple-ace. The following day, September 16, while the Australian forces marched victoriously into Lae, Lynch scored again. He was now tied at sixteen with Dick Bong, who was returning to action.

Before Bong pulled back into the lead with his seventeenth victory on October 2, Tommy McGuire had upped his own score to seven, with two victories on September 28. Despite the dry spell for all of them over the following week, things were shaping up to erase any lingering doubts about the combat prowess of the P-47 Thunderbolt.

October 11, 1943

The weather over Papua, New Guinea, improved greatly after the first week in October, and several flights of Kearby’s P-47s were busily engaged in routine and uneventful escort cover for transports to Nadzab. The morning sky was clear, and with most of his pilots protecting troop and supply movements, Lieutenant Colonel Kearby believed it might be the perfect moment for a free-roving patrol to seek out enemy aircraft in the Wewak area.

In preceding weeks Kenney’s fighters had so dominated the air that it was getting harder and harder for his pilots to find targets and score victories. Kearby had long been a proponent of using his fighters not only defensively, as protection for troop movements, but as offensive tools to freely roam the region tempting the Japanese to come out and fight. The morning of October 11 seemed the perfect moment to test that strategy.

Captain John Moore, as operations officer for the 341st Squadron, was not scheduled for any of that day’s missions and volunteered to fly as Kearby’s wingman. Major Raymond Gallagher, who commanded Kearby’s 342d Squadron, volunteered to join the two men, and Captain Bill Dunham agreed to fly wing for Gallagher. Thus, were the circumstances that saw the Group’s ranking officers depart Ward’s Drome at 9:30 a.m. for a flight Brigadier General Uzal Entht west to Wewak, while the rest of the Groups pilots were tending to their mundane patrols around Nazdab.

Cruising west at 28,000 feet, by eleven o’clock Kearby’s flight of four Thunderbolts had a clear, panoramic view of the Wewak area fifty miles ahead and five miles below. Kearby instructed his pilots to drop their wing tanks and prepare for action. With fuel now limited, he hoped that the enemy would rise quickly to the bait.

In fact the enemy had already risen to the bait. Lieutenant Colonel Tamiya Teranishi, commander of the Japanese 14th Fighter/Bomber group, was visiting Wewak when radar picked up the incoming Thunderbolts from fifty miles out. He ordered numerous fighters airborne from their fields in the vicinity, then climbed in an Oscar himself and took off to lead the intercepting force. Once rendezvoused with the other fighters he had called into action, his flight would number more than two dozen armed fighters: nimble Oscars and deadly Tonys.

At 11:15 Lieutenant Colonel Kearby became aware of a lone plane more than a mile below him and off to the left. The Jap plane apparently could not see the incoming Thunderbolts, which were flying east-to-west out of the sun. There was no evasive action by the enemy pilot. Kearby went into a screaming dive, closing in to positively identify the lone airplane as Japanese by the bright, red meatballs on its wings. Kearby opening fire when he had closed to within 300 yards. The devastating fire tore holes in metal and ruptured the fuel tanks, sending the Oscar and surprised pilot plummeting earthward like a flaming comet. (Post-war Japanese reports of the October 11 combat action indicated that the last communication the fighters rushing to join Lieutenant Colonel Teranishi in the air received from their commander came at 11:25 a.m. Neel Kearby had not only claimed his fourth victory, but most probably was responsible for the death of a Japanese hero and group commander.)

Kearby’s trailing Thunderbolts had nothing left to shoot at as they passed through the trailing smoke of Teranishi’s falling Oscar, moments behind their leader. Then Major Gallagher spotted a lone fighter off the coast, a few miles out to sea and heading towards Wewak. Diverting from his three comrades, he sped off alone to try and claim what would be his first victory. The enemy fighter spotted the incoming Thunderbolt moments before Gallagher reached combat range and wisely ducked into a nearby cloud. Disappointed, Gallagher headed back towards the island to rejoin his comrades. Below he saw nothing but jungle, to the right and left he could see nothing but blue sky. He had spent too much time chasing the elusive enemy fighter and now was far behind Kearby and the two other American pilots. It was a cruel turn of luck, for even at that moment the ranking officers of the 348th Fighter Group were about to engage in the fight of their lives–and an historic one at that.

After shooting down the Oscar, Kearby lead his formation back up to 26,000 feet for one final pass over Wewak. There were no more planes in sight, including Major Gallagher’s, so he planned to make one final sweep and then head for home. Kearby assumed they would rendezvous with Gallagher en route.

Any mission where a flight got even a single victory without losing one of their own was a successful mission, and Kearby would not lament the lack of additional targets, or make the deadly error of staying too long and running out of gas on the way home. The mission appeared to be complete when he heard Captain Dunham’s voice over the radio announcing, “We’ve got bogeys coming in from the coast…lots of ’em!”

“I see them,” Captain Moore answered back. “I count about a dozen of ’em, maybe more…mostly Tonys I think, with a few Zekes and Oscars.”

Kearby looked off in the distance towards the enemy field at Boram and it was hard to miss the large formation of fighters, cruising at 15,000 feet two miles below. A quick count revealed more than a dozen of them. Undoubtedly, they were the aircraft that had scrambled earlier on Lieutenant Colonel Teranishi’s alert, and which were now looking for any sign of their silent Japanese commander. None seemed to be aware of the Thunderbolts in the distance and miles above them.

Four miles out to sea and about fourteen miles from the airfield, Kearby saw another flight of at least a dozen Japanese bombers. They were probably returning from a mission and flying casually home at 5,000 feet. The air was suddenly filled with targets. It was the kind of shooting gallery any hot-shot fighter pilot would love to find, unless… he was outnumbered at least eight-to-one as Kearby and his two other Thunderbolts were.

“Let’s take ’em,” Captain Dunham said eagerly. He had not yet scored his first victory and Moore had only one. Suddenly, it seemed, they had the whole Japanese air force in their sights, and both young officers were itching for a fight. Kearby understood their eagerness, recognized the excitement in their voices, and recalled the moment he had sighted his own first target. He also remembered how, in his adrenaline-soaked eagerness, he had nearly endangered the mission. Kearby the tactician would not make the same mistake twice. Before issuing orders, he reviewed the combat situation that was building, and this time he remained cool and calculating.

“Hang on guys. We’ll get them, but let’s get in position first. Follow me. They don’t see us. We’re miles above them. This is the moment we’ve been waiting for, the chance to dive out of the ceiling on an unsuspecting enemy and tear them apart.” At last, after routine missions and luck-of-the-draw air battles limited by the tactic of waiting for enemy fighters to attack, Kearby’s Thunderbolts had the opportunity to do what they had been designed to do–go on the offense.

Kearby moved his flight behind the fighters, leveling off 8,000 feet above them. Still unseen, the P-47s were poised to strike. When they did, the attack came with unstoppable fury, three Thunderbolts screaming downward and into the enemy formation at 425 miles per hour. A dozen 50-caliber machine guns spewed lethal, half-inch rounds. Before the enemy pilots even knew they were under attack the lead Oscar burst into flames and spiraled into the surf along the New Guinea coast. Neel Kearby had just become an ace!

Even as the first victim fell and Kearby turned to attack and destroy his third Oscar of the day, one of the trailing Jap pilots recovered quickly and slipped his armed Tony in on Kearby’s tail. Moments before the enemy pilot could unleash his guns on the American flight leader, the Tony itself began to shudder under a withering hail of machine-gun bullets. Captain Dunham had been on his commander’s wing when the Thunderbolts went into a dive, and had quickly slipped in to cover Kearby’s tail. As the enemy formation scattered, there was no time for Dunham to exult in his own first victory. That would come later. The Thunderbolts were now at lower altitudes where their maneuverability could not match that of the remaining enemy planes. The celebration would have to wait…right now it was time to fight.

Captain Moore resisted the urge to dive into the fray. It was hard to watch the ongoing fight and not be a part of it but, as the trailing aircraft, it was Moore’s responsibility to hang back far enough to see everything that was happening and pounce immediately if another enemy fighter got on Kearby’s tail. Mentally he ticked off the tally: one for Dunham, three now for Kearby, and the unstoppable Texan wasn’t ready to let any enemy pilot prematurely lay claim to the title “survivor.”

Even before Dunham’s kill hit the ground to explode in the jungle, another Oscar felt the wrath of Kearby’s guns, spiraling downward to start its own fire in the foliage below. “My God, four of them,” Captain Moore said to himself in amazement. “And all in less time than it takes to light a cigarette.”

Before the enemy could scatter further, Moore finally got a kill of his own. It was his second in three weeks, bringing the day’s total to SIX for the three pilots. And then, with all enemy opposition fading quickly into distant clouds for protection from the man who had shot down four of their comrades in mere seconds, Moore executed a series of lazy circles through the area, counting fires and confirming his victory and those of his two friends.

When the last targets vanished, scattering for safety, Major Gallagher flashed in from the sea. He located his flight leader from the signs of combat but it was too late to engage the enemy. Below him, both surf and jungle burned with at least half a dozen fires, mute testimony to the great battle that had just taken place. The fight was over and low on fuel, Kearby, Gallagher, and Dunham headed for home.

Behind the lead fighters and still out of visual contact, Captain Moore climbed to 16,000 feet to catch up to his three comrades. It was twenty miles before he, at last, saw caught sight of one of the homeward-bound Thunderbolts. It appeared to be alone, 4,000 feet below him and surrounded by a swarm of Jap fighters. Moore saw the P-47 pilot destroy one of the attacking Tonys but it was obvious the American had bitten off more than he could chew when he had single-handed attacked the formation. Any man that gutsy had to be Kearby, and if it was, then the pilot below him had just destroyed his fifth enemy aircraft -an ace in a day!

Diving to the rescue, Moore lined up on the last Tony in a flight of three. His first burst ruptured oil lines and the fighter began trailing smoke. A second volley turned the Jap fighter into flaming, molten metal, devoid of an airfoil and dropping like a rock.

“Bingo!” He shouted in exuberance. It was his second victory of the day, third so far in the war. Then he looked in his mirror and his celebration turned to horror. The other two Tonys were lined up on his tail and closing fast. Almost within firing range, Moore felt the hairs rise on the back of his neck and dove as hard and fast as his seven-ton fighter would fall. He expected at any moment to feel the wrath of the enemy guns shredding his body.

In the distance, Neel Kearby saw Moore’s desperate dive and was amazed that the two Tonys were keeping pace. For all its diving inertia, the Thunderbolt couldn’t shake the two Jap fighter’s intent on salvaging some honor from this day of battle. Kearby was extremely low on fuel and ammunition but it wouldn’t stop him. Winging over, he put his own airplane into a desperate dive, coming up quickly on the last of the two Tonys in pursuit of his wingman.

Kearby was still 1,000 yards out, well beyond the range for even the best aerial gunners, but he couldn’t wait any longer–it was now or never. He triggered his guns, feeling his downward motion braked by the recoil of the eight huge 50s, throwing him forward to strain against his shoulder harness. The guns on one wing chattered to a halt, out of ammunition and threatening to skew his forward momentum against the unequal force. Kearby fought the controls to stay in line with the enemy while the remaining guns nearly cut Tony into two pieces. Diving through the exploding shrapnel he continued to fire, unsure if his bullets were striking the last attacker. Winging over, he came in from the 10 o’clock position for a final pass at it but the angle seemed wrong. Kearby was pretty certain he hit the Tony; thought he saw smoke trailing from what would be his seventh victory of the day.

Whatever the case, whether falling in death or retreating in utter fear, the last fighter vanished and Kearby couldn’t stick around to confirm his final kill. Slipping alongside his wingman, the two victorious pilots headed for home.

The fact that Lae was now in Allied hands may have been the only thing that got all four men home safely. With an average of 50 – 75 gallons of fuel remaining, they would have had difficulty reaching Marilinan or Dobodura. After landing and refueling at Lae, the four officers flew up and over the Owen Stanley range to land at Port Moresby. Before leveling off to land, each man took the time to fly over and perform the traditional victory rolls. Captain Dunham made one roll, Captain Moore two rolls, and Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby an unprecedented seven rolls.

After taxiing to a stop Kearby reported to General Kenney, who at the moment was engaged in a planning session with General MacArthur, who had flown in the previous day. After hearing Kearby’s report of the mission Kenney advised MacArthur, “The record number of official victories in a single fight so far is five, credited to one of the Navy pilots, and he was awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor for the action. As soon as I can get witnesses’ statements from the other three pilots and see the combat camera-gun pictures if Kearby got five or more I want to recommend him for the same decoration.”

General MacArthur advised Kenney that if Kearby’s tally was verified, he would approve the recommendation and forward it to Washington. Both top commanders extended hearty congratulations to Kearby for his unprecedented, historic one-day combat action.

By the time of Neel Kearby’s great air battle over Wewak, a total of sixteen Army airmen had earned Medals of Honor, eight of which had already been presented. All sixteen of these heroes, however, had been bomber pilots or crewmen (with the exception of Hamilton and Craw who received their awards for actions on the ground.)

By the fall of 1943, the U.S. Navy had fighter pilot heroes like Butch O’Hare and John Powers, both of whom were dead or missing. The Marine Corps had posthumously honored the heroism of fighter pilot Henry Elrod at Wake Island in the opening weeks of the war, as well as other fighter pilot heroes like Richard Fleming. The Cactus Air Force, flying out of Guadalcanal, had produced a number of Marine Corps Aces, several of whom earned Medals of Honor in the fall and winter of 1942. One of them, Joe Foss, had tied Eddie Rickenbacker’s record twenty-six victories before being sent home to receive the Medal of Honor. In fact, during World War II only three Medal of Honor heroes had the distinction of appearing on the cover of Life magazine. Two of them were Marine fighter pilots who had battled at Guadalcanal in the early days of the war, John L. Smith and Joe Foss. (The other, in 1945, was Audie Murphy.)

The Army Air Force was certainly not without heroes of its own, from Buzz Wagner to Richard Bong, whose tally was up to seventeen. But for whatever reason, nearly two years into the war and with hundreds of Japanese planes overgrown in ruin on the jungle floor, or resting at the bottom of the ocean, not a single Army Air Force fighter pilot had yet earned the Medal of Honor.

Furthermore, though Kearby’s unofficial tally of seven victories in a single battle was the greatest single-day effort in Fifth Air Force history, it was not unprecedented. Nearly a year earlier, on October 26, 1942, Navy pilot Stanley Swede Vejtasa had shot down seven Japanese planes in defense of the USS Hornet & Enterprise during the Battle of Santa Cruz. Two days before Kearby’s historic air battle, one of his closest friends from his days stateside Major Bill Leverette shot down seven enemy aircraft in a single battle in the Mediterranean. Neither of those two super-aces received the Medal of Honor.

From a historical standpoint, there are some who look at Neel Kearby and compare him to leading aces of his day like Bong and Lynch, or the air hero of the Day of Infamy George Welch. Some will quickly point out that Kearby’s Medal of Honor nomination was a result of his close friendship with General Kenney. Certainly, from the day Kenney met the cool-as-ice fighter pilot from Texas and saw the hunger in his eyes, Kearby earned something akin to a favored son status with the Fifth Air Force Commander. That relationship blossomed, perhaps, because General Kenney saw in Kearby a ghost from his own past, the personality and abilities of a World War I pilot hadn’t been afraid to set goals for himself, and then used his aerial prowess to make believers out of anyone who doubted him…until the day of his untimely death.

Whatever the motivation, Neel Kearby’s action on October 11, though not unprecedented, was a new benchmark in the Fifth Air Force. Ultimately, only six of his victories over Wewak were confirmed. The seventh, if indeed it had been a legitimate shoot-down, had come late in the action when all four pilots were attempting to break free and head for home. The gun cameras confirmed Kearby’s first six victories beyond doubt. The film, however, ran out just as Neel’s bullets began to strike his seventh target. Kenney recalled, “I wrathfully wanted to know why the photographic people hadn’t loaded enough film, but they apologetically explained that this was the first time anyone had ever used that much (film.) They hadn’t realized that enough film to record seven separate victories was necessary but, from now on, they would see that Kearby had enough for ten Nips.”

The true value of Kearby’s accomplishment was not reflected, however, in the six victories he was officially credited with. Rather, it was reflected best in the after-action report written by 342d Fighter Squadron Intelligence Officer, First Lieutenant Bernhard Roth:

“….A total of 9 (enemy) fighters destroyed without a scratch on a single Thunderbolt demonstrates that this type of plane has come into its own in this theater, and that its terrific speed both in the dive and straightaway, its flashing aileron roll, and murderous firepower will henceforth strike terror into the hearts of the little yellow airmen.

“In conclusion, it should be noted that this plane flew well over 300 miles, fought for one hour, and returned, the whole mission consuming about three hours and one half. About 3500 rounds of ammunition were expended and over 100 feet of film taken.”

On January 23, 1944, Colonel Neel Kearby received his Medal of Honor from General Douglas MacArthur in his office in Brisbane, Australia. Kenney recalled: “The General did the thing upright and so overwhelmed Neel that he wanted to go right back to New Guinea and knock down some more Japs to prove that he was as good as MacArthur had said he was.”

On the day Colonel Kearby became the first Army Air Force fighter pilot to receive his country’s highest honor in World War II, his score had increased to twenty-one victories. More importantly, in five months of combat Kearby’s Thunderbolts had knocked down an incredible total of 164 enemy planes (confirmed,) and scores more that were probable but unverified victories.

The value of the once derided Thunderbolt would never again be questioned. It would emerge one of the greatest pursuit airplanes of World War II, legendary in is an accomplishment and exceeded perhaps, only by the legend of the man who led them…

and his plane Fiery Ginger

At the same time General Kenney submitted his report verifying Kearby’s six single-day victories in support of a recommendation for the Medal of Honor, Kearby was promoted to Colonel. In the weeks that followed Neel pushed himself, not only to try and catch the elusive Dick Bong but to achieve his personal goal of fifty aerial victories. Five days after his big day over Wewak, Kearby upped his score to ten. He brought it to a dozen with a double victory on October 19.

In addition to the promotion, and during the months before his Medal of Honor was approved, Kearby was decorated again and again. In all the driven fighter pilot earned two Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, and five Air Medals.

On October 29 Dick Bong returned to action, adding two more victories to his own score. On November 5, a second consecutive double-punch victory brought the leading Fifth Air Force ace’s total to twenty-one. Kearby, at that time, remained at a dozen.

General Kenney had promised Bong a leave to return home when he reached twenty victories, and Dick Bong wasn’t hesitant to accept the offer. In December Bong departed for the quiet life of Wisconsin, or at least as quiet a life as his newfound fame would allow. For Kearby, it was the opportunity to catch up. He wasted no time getting to work. General Kenney had reassigned Kearby to the Fifth Fighter Command, a position that left him free to fly–and to roam–all areas of operations at will. It was Kearby’s opportunity to at last engage in the kind of unrestricted, offensive combat he had yearned for since his arrival six months earlier.

On December 3 Kearby had his best day since the October 11 battle, destroying three Zekes twenty miles northwest of Wewak. Single victories on December 22 and 23 increased his score to seventeen. On January 3 a double victory put him at nineteen, and another double victory on January 9 brought the total to twenty-one. Kearby and Bong were tied on January 23 when MacArthur pinned the Medal of Honor on Colonel Kearby’s chest.

General Kenney did attempt to slow Kearby down, fearful that the intense drive that pushed the young pilot nearly beyond reason would ultimately become his downfall. More and more he tried to keep Colonel Kearby occupied with administrative duties, but there was no keeping the man who wanted to be the greatest fighter pilot of all time out of the air. Kenney noted the difference between the personalities of Kearby and Bong when he wrote his memoirs after the war.

“I told Kearby not to engage in a race with that little Norwegian lad. Bong didn’t care who was a high man. He would never be in a race and I didn’t want Kearby to press his luck and take too many chances for the sake of having his name first on the scoreboard. I told him to be satisfied from now on to dive through a Jap formation, shoot one plane down, and come on home. In that way he would live forever, but if he kept coming back to get the second one and the third one he would be asking for trouble.

“Kearby agreed that it was good advice but that he would like to get an even fifty before he went home. I said I wished he would try to settle for one Nip per week.”

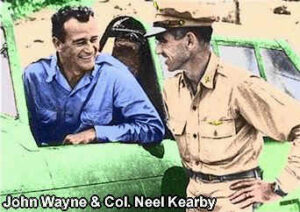

Colonel Kearby would have been wise to heed Kenney’s advice, but with his status as the hottest gun in the Pacific, Neel felt personal pressure to live up to his reputation. Throughout the month of February, it was as if he was flying with abandon, setting the standard for the younger pilots to follow, while striving to attain the standards he had set for himself. Kearby was a celebrity among his men, in the newspapers back home, even to other up-and-coming celebrities like John Wayne who visited the theater on a goodwill tour. Neel Kearby was determined to be worthy of that celebrity status.

By this point in time in early 1944, the Fifth Fighter Command had nineteen squadrons, eleven of which were equipped with the hottest fighter in the Pacific, P-47 Thunderbolts. Seldom were they any longer called “Jugs.” Colonel Kearby’s leadership skills were becoming increasingly more important than his personal combat skills, especially with the infusion of new pilots. The squadrons of the 348th Fighter Group were now led by seasoned, combat veterans. The pilots themselves continued to rack up an impressive record of victories, including one young pilot named George Davis who by February had two victories and would go on to become an ace among Kearby’s Thunderbolts, then repeat the feat a few years later in Korea where he would earn a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Such administrative and training responsibilities aside, when Dick Bong returned and was assigned to Fifth Fighter Command on the same free-lance status as Neel Kearby, the pressure on Neel mounted. Bong wasn’t threatened by the existing tie between Kearby and himself, in fact, had the two men flown together and attacked the same aircraft at the same time, Bong would never have argued the point–he would simply have allowed Kearby the credit. This was the difference in their personalities. Bong was having fun. Kearby was pushing himself to prove something.

Jap fighters were becoming more and more scarce as the Fifth Fighter Command took control of the sky, and Kearby was finding fewer and fewer potential targets. Time and again during the month of February he flew with various groups, hoping to get lucky. On the rare occasions when enemy fighters were found, the best Kearby could claim was probable here and there. None were confirmed. Bong’s fun in the air put him back in the lead with a victory on February 15.

When Tommy Lynch returned from R & R, he too was assigned to Fifth Fighter Command under the same free-to-roam status. In fact, Lynch and Bong began flying missions together–two of the three top Pacific aces hunting together and covering each other’s tail. On one such joint incursion into enemy territory near Tadji on March 3, each of them scored twice.

March 5, 1944

Dick Bong and Tom Lynch were out hunting together again early on the morning of March 5. The day was quiet enough and there was no action to be found. The two men were nearing Dagua, southeast of Wewak, at about 1:30 in the afternoon. The two aces, at last, found a lone Oscar and, within minutes, Tom Lynch had closed to within one victory of Kearby.

Frustrated with his own lack of success, and realizing that Bong was within two victories of tying Rickenbacker and three of becoming the first pilot to exceed the World War I Ace of Ace’s record, Kearby was feeling the pressure to act quickly. It is important to note that the pressure was purely self-induced, heaped upon the man’s mind only by his own personal drive to be the very best. Everyone else, from General Kenney to Kearby’s closest friends, had done their best to rein him in and talk him out of continuing his fearless, headlong dives into enemy formations. It seemed that Kearby felt invulnerable in his mighty Thunderbolt. The other pilots who admired the brash and skillful Texan feared that he wasn’t, despite the aura of strength, determination, and near super-human ability that surrounded him.

Perhaps encouraged by the fact that Lynch had managed to find an enemy Oscar in the Wewak area, and certainly pressured by the fact that not only might Bong beat him to Rickenbacker’s benchmark but that Lynch was quickly moving towards the second place, Kearby had to get airborne. According to some reports, Kearby’s legendary airplane Fiery Ginger IV was down for repair and the unrestrainable airmen borrowed another P-47. (To this day there remains some controversy as to what plane Neel Kearby was flying on that fateful, last mission. More recent investigations tend to support the idea that Kearby actually flew his last mission in Fiery Ginger IV, his famous P-47.)

Kearby induced Major Sam Blair and Captain Bill Dunham to follow him in a late afternoon sweep over Wewak. Kearby led them into the air at 4:30 in the afternoon and headed east, where two days earlier Bong and Lynch had each scored twice. Fifty minutes later, en route to Tadji, Kearby was patrolling the coastline near Wewak from an altitude of 22,000 feet when he spotted a lone Tony approaching the Dagua airstrip. Positioning himself for the kind of dive that had repeatedly granted him victory over the enemy, Kearby felt his excitement turn to disappointment when the Tony leveled off to land. The enemy pilot would be on the ground before the American ace could get within firing range, and the only kills that counted on the scoreboard were aerial victories, not airplanes destroyed on the ground.

Kearby and his two wingmen continued their patrol, hoping to salvage something from the mission before the shadows of dusk crept over the jungle. Suddenly Dunham’s voice crackled over the radio. “There they are…I make out three of them, coming in low.”

“I see them,” Kearby announced. “Nice little V formation. Drop your tanks guys, and let’s nail them.”

Glistening orbs of near-empty wing tanks fell away as the three Thunderbolts nosed down into a lethal dive. Four miles passed in less than a minute, the formidable fighters gaining speed as the gravity sucked them earthward even as mighty engines whined in protest to the extreme speed. The three enemies were circling less than 1,000 feet above the jungle floor, apparently planning to land at Dagua, Before Kearby and his men reached firing range the Jap pilots saw them coming and scattered. Kearby pointed his nose at the lead fighter, opening fire when the two were down to 200 feet above the ground.

As he dove past the scene of the initial action hot on the tail of the fighter on the right, Major Blair saw what looked like two aircraft burst into flames on his left. While Kearby had been firing on the lead fighter, Dunham was flaming the outside wing of the V formation. Blair stayed on the tail of his own target, opening fire 200 yards out and watching a stream of bullets sending it down in flames. At the extremely low altitude, it took only seconds for the Jap fighter to explode into a fireball on the jungle floor. Blair banked and climbed quickly to avoid driving his own fighter into the foliage below.

Kearby was breaking to the right and trying desperately to climb, an Oscar on his tail. The Americans had initially attacked three planes, Japanese Nell or Lily bombers. Behind these, there had apparently followed three more Vs, each with at least three enemy aircraft. Several of them were now on Blair’s tail as he dove for the protection of some low-hanging clouds. Before he disappeared into the white mist he saw Dunham streaking in from the front of Kearby’s besieged Thunderbolt, laying a head-on burst into the Oscar that was bent on claiming victory over the second-leading Army ace in the Pacific. Flashing past his commander as the two P-47s crossed in opposite directions, it looked for a moment as if Kearby’s canopy was opening. And then the two fighters were out of visual range. Dunham continued on to join up with Blair.

It was dangerous to remain in the area, but the two men circled as they climbed, scanning the distance for their third man. No sign of Kearby’s Thunderbolt could be found in the fading twilight. Low on fuel, the two pilots headed home, hoping to find Neel Kearby waiting for them on the ground.

It was not to be.

The minutes ticked slowly away while scores of American airmen stood by at the airfield, scanning the darkening horizon and expecting to see a P-47 limping in. It was inconceivable that the indestructible Neel Kearby was gone. By the time full darkness had fallen over the South Pacific, however, even the most optimistic among the believers had to confront reality — Neel Kearby was gone.

Two years after the end of World War II a RAAF search party found the wreckage of a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt near Pibu, a small village on the northern coast of New Guinea. After inquiring from local natives, the Australians learned that an American airman had parachuted to the ground shortly before his Thunderbolt crashed. Reports varied. Some claimed the airman was dead when he hit the ground, having jumped from an extremely low altitude. Other reports claimed the airman had got caught in the trees and died from gunshot wounds. The natives had stripped the body, then buried him nearby.

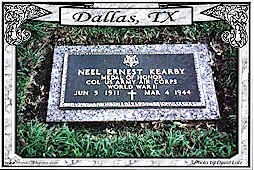

For two years the skull and a few bones recovered by the natives and turned over to the Australians were marked “Unknown X-1598” and kept at the American Graves Registration Service Mausoleum in Manila. In 1949 they were at last formally identified as the remains of Colonel Neel Kearby, the first Army fighter pilot of World War II to receive the Medal of Honor.

Colonel Neel Kearby came home on an Army Transport on June 16, 1949. Six Army Colonels flew to Dallas, Texas, to act as pallbearers for the World War II legend whose belated return was little noticed.

Neel Kearby was buried with honors at Hillcrest Memorial Park in Dallas on July 23, 1949. In an ironic twist of fate, over the years that followed, all three of Neel and Virginia’s children also died in aircraft accidents.

The loss of Colonel Neel Kearby was felt throughout the Army Air Forces. The tragedy was compounded four days after Kearby’s death when, while on a sweep over Tadji, Dick Bong watched in horror as Tommy Lynch parachuted to his death from his flaming P-38. In Washington, D.C., Hap Arnold sent messages to his Air Force commanders in all theaters of operation, questioning whether it was wise to continue to allow leading aces to fly combat, “When their loss may become a national calamity…We are getting a rash of aces and we are losing them in many cases because the individual score means more than the squadron score.”

Perhaps the most rational response was written by the new Eighth Air Force Commander in England, General Jimmy Doolittle, who had been the first airman of the war to earn his nation’s highest honor. He wrote Hap to note:

“Inevitably, some heroes develop, for in a large number of officers there are always a few whose capabilities and accomplishments make them outstanding. A combat leader must lead to maintain the excellence of his unit and the respect of his subordinates. Some leaders will therefore inevitably be killed.”

Deeply saddened by the loss of his close friend Tommy Lynch and the hard-charging Neel Kearby, Dick Bong managed to emerge from his own grief without self-doubt. Despite the fact that aerial combat had never been a race for him, after a single victory on April 3 and a triple victory nine days later, Dick Bong became the first airman to surpass Eddie Rickenbacker’s record with 28 victories. Before his own war ended, the young man from Wisconsin would emerge as the new Ace of Aces with a total of 40 victories.

In many ways, not the least of which was the fact that like his predecessor Dick Bong didn’t see himself in a race for first place but simply as an airman doing his job, the young man was a World War II incarnation of the Ace of Aces of the first World War. During that first war Eddie Rickenbacker had watched a more competent gunner than himself, a man with uncanny skill in the cockpit and a master tactician, drive himself to prove that he was the best fighter pilot in the Army Air Corps. At the time Rickenbacker noted,

“Luke will be the greatest pilot that ever flew…if he lives long enough.”

If then, Dick Bong was the second war’s Eddie Rickenbacker, one might well understand the forces that drove Neel Kearby by realizing he was World War II’s Frank Luke–fearless, skilled, and driven to prove he was the best. For both men, it was that drive that ultimately led to their death. In fairness, it was also that same drive the caused them to indeed be the greatest fighter pilots alive–while they lived.

About C. Douglas Sterner

In 1998, C. Douglas Sterner launched the Home of Heroes website to document the citations and biographies of our Nation’s Medal of Honor recipients. His research led him to expand the site's mission to include other medal recipients that have been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, and others.

Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC took over the site in mid-2018. We are grateful for Doug's faithful management of the site and vow to maintain the site with the same integrity.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED