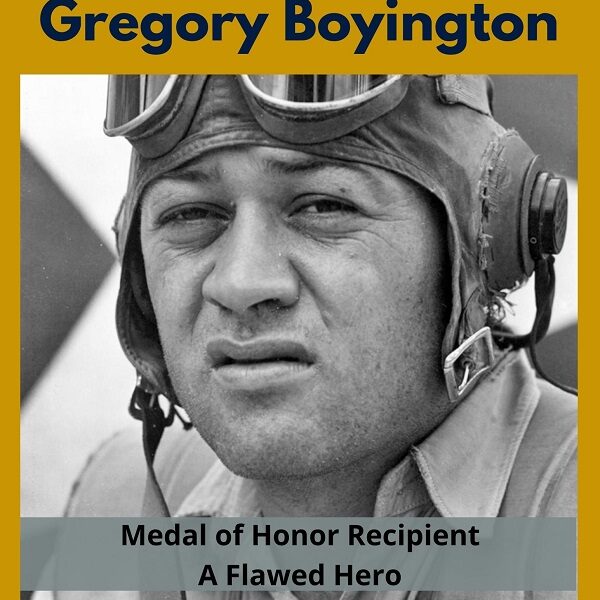

Gregory Boyington

A Flawed Hero

By James G. Fausone

It may be polite to only focus on the positive exploits of Marine heroes, but to tell the true story it is important to recognize the faults and flaws that many of our Marine heroes had to overcome on the road to fame. Gregory Boyington certainly had many faults and flaws. He also had the capacity to recognize his faults, if not overcome them, and learn from other men when given good advice. Those faults and flaws never stood in the way of him serving the country and meeting his duties as a United States Marine.

Col. Gregory "Pappy" Boyington (ret.), USMC was the "bad boy" hero of World War II that America needed in the Pacific Theatre. He led an ad hoc squadron of fliers known as the Black Sheep. The exploits of Pappy and his cohorts were captured in Boyington's autobiography, "Baa Baa Black Sheep," in 1958. He writes well after World War II when he has had time to reflect on his combat actions and time being a prisoner of war. But Boyington acknowledges the bad boy reputation was warranted and maybe cultivated. He proves there is hope for greatness even through the screw-ups, daredevils, and drunks.

A television show in the 1970s made Pappy's Black Sheep wildly known to new generations. In 1970, Boyington and his squadron's unusual and often insubordinate antics were brought to life in a popular television show. Released as "Baa Baa Black Sheep," with Robert Conrad starring as Boyington; it was renamed "Black Sheep Squadron" in its second and final season. The series itself was part military drama and equal part comedy, due in no doubt to Boyington's unusual but true-to-life characteristics. If some of the antics seem incongruous, those who knew Pappy Boyington knew that it was an uncannily realistic portrayal of an uncommon man and a unique Marine Corps Hero.

The Pacific Northwest Culture

Greg was born on December 4, 1912, in beautiful Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. The panhandle of Idaho has more in connection with Washington state than southern Idaho. It is dominated by a deep and pretty lake and is now considered up-and-coming. In the 1900s, it was very rural and known as a timber country. He had Irish and Brule Sioux (a Lakota tribe) blood and genetics.

Native Americans have demonstrated their patriotism and war spirit by defending the United States of America for decades before they were recognized as citizens. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship to the indigenous peoples of the United States. It was enacted partially in recognition of the thousands of Native Americans who served in the armed forces during World War I. The Irish are also known for their patriotism and willingness to mix it up, particularly when alcohol is involved. An overly broad generalization, but one has to wonder if Boyington's genetics may be a reason he was such a fighter and a drinker.

The family ultimately moved to Tacoma, Washington, where he was a wrestler at Lincoln High School. After graduating from high school in 1930, Boyington attended the University of Washington in Seattle, where he was a member of the Army ROTC. He was on the Husky wrestling and swimming teams, and for a time he held the Pacific Northwest Intercollegiate middleweight wrestling title. Wrestling was to be part of his life after the war. He spent his summers working in Washington in a mining camp, a logging camp, and with the Coeur d'Alene Fire Protective Association in road construction.

He graduated from college in 1934 with a bachelor's degree in aeronautical engineering. Aviation was clearly in his blood as he took his first plane ride when he was 6 years old. Boyington married in the fall of 1934 for the first time. His wife, Helen Clark, was 17 years old and bore him three children. Greg married Helen under his then-name of Gregory Hallenbeck. He worked as a draftsman and engineer for Boeing in Seattle. His parents, the Hallenbeck's, maintained an apple ranch in Okanogan, Washington.

Bending the Rules

Hallenbeck had been a member of the Husky's Army ROTC program. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Reserve in June 1934 after graduation and then served two months of active duty with the 630th Coast Artillery at Fort Worden, Washington. In the spring of 1935, he applied for flight training under the Aviation Cadet Act, but he discovered that it excluded married men. Boyington had grown up as Gregory Hallenbeck and assumed his stepfather, Ellsworth J. Hallenbeck, was his biological father. However, upon receiving his birth certificate, Greg learned that his biological father was actually Charles Boyington, a dentist, and that his parents had divorced when he was an infant.

Greg really wanted to fly. Less than a year after being married, he used the name "Gregory Boyington" to enroll as a U.S. Marine Corps aviation cadet. There was no record of Gregory Boyington being married. That also meant he could not claim any benefits of having a spouse or dependents at that time. But Greg wanted to fly, so he left his Army commission life behind.

By June 1935, he was in the U.S. Marine Corps Reservist on inactive status. He was assigned to Naval Air Station Pensacola for flight training. Boyington was designated a Naval Aviator on March 11, 1937, then transferred to Marine Corps Base Quantico for duty with Aircraft One, Fleet Marine Force. He was discharged from the Marine Corps the following day. Boyington attended The Basic School in Philadelphia from July 1938 to January 1939. On completion of the course, he was assigned to the 2nd Marine Aircraft Group at the San Diego Naval Air Station. he took part in fleet operations off the aircraft carriers USS Lexington and USS Yorktown. Promoted to first lieutenant on November 4, 1940, Boyington returned to Pensacola as an instructor in December.

Boyington was always looking to hop from one exciting possibility to the next. As Boyington wrote in his book, "I never completely got out of one situation before getting into another." This was a challenge for the family and the three children he had with Helen. He was away a lot, even before the war, seeking the next adventure and paycheck. While he remained married for seven years, the financial burdens of family life always trailed him. Boyington, a father who was never around, claimed Helen neglected the children and they were placed with his parents. Their divorce naturally followed in 1941.

Flying Tigers

The next crazy opportunity came along in August 1941. Boyington resigned from his commission in the Marine Corps to accept a position with the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO). CAMCO was a civilian firm that contracted to staff a Special Air Unit to defend China and the Burma Road from the Japanese. This later became known as the American Volunteer Group (AVG) or more commonly known as the "Flying Tigers" in Burma.

This was not about flying, fighting the Japanese, or defending the Chinese. Boyington was sure that between his financial problems and drinking he would be passed over for captain in the Marine Corps. This opportunity was simply about a paycheck. Boyington, as always, was in trouble with creditors and the IRS and needed to make some quick cash. He was convinced that flying for CAMCO would lead to easy money. The group had contracts with salaries ranging from $250 a month for a mechanic to $750 for a squadron commander, roughly three times what they had been making in the U.S. Military.

The AVG was the brainchild of retired Army Air Corp Officer Claire Chennault. About 300 men were recruited by CAMCO - about 100 of whom were pilots from the Navy, Marines, and Army Air Corps. Boyington was told that upon resignation from AVG, he could be reinstated with rank in the Marine Corps. This 28-year-old believed that bonus pay from shooting down ill-equipped Japanese planes would get him above water financially and then he would come back to the Corps. He is credited with six air-to-air victories in his time with AVG. Like most of military life, it is a lot of time waiting around. Boyington filled those hours up arguing with his commanding officer, drinking copious amounts of whiskey, and enjoying the local women.

During his time with the Flying Tigers, Boyington became an accomplished flight leader but he was frequently in trouble with his commanding officer, Claire Chennault. This pattern would repeat itself during his military career. In April 1942, he broke his contract with AVG and returned on his own to the United States. The roughly eight months in AVG did expose Boyington to real dog fights, that Japanese pilots were skilled and certain flying techniques would save your life. While he became a better pilot, he did not become a better man.

During his time with the Flying Tigers, Boyington became an accomplished flight leader but he was frequently in trouble with his commanding officer, Claire Chennault. This pattern would repeat itself during his military career. In April 1942, he broke his contract with AVG and returned on his own to the United States. The roughly eight months in AVG did expose Boyington to real dog fights, that Japanese pilots were skilled and certain flying techniques would save your life. While he became a better pilot, he did not become a better man.

Back in the Marine Corps

While in AVG, the United States declared war after Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Boyington was itching to get back in the fight with the Marines. His expectation was that the paperwork he signed prior to AVG was a golden ticket, but it was never going to be that easy. He sought reinstatement and was told to go back to Washington State and wait. Without a paycheck, clothes, or a purpose, the next three months found Boyington parking cars for 75 cents per hour, the same job he had in high school. After a fifth of bourbon, he wrote a three-page letter for reinstatement and sent it to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. That ranting letter may be lost to history, but it had the impact of getting him active duty orders and ultimately back in the fight in the Pacific.

The Solomon Islands

Major Boyington found himself sent to the Solomon Islands where the Allies were stopping the Japanese advance and attempting to turn the tide and attempting to turn the tide and regain land acquired. In late January 1943, the battle for Guadalcanal wrapped up and Operation Cleanslate, the occupation of Russell Islands, was next up. U.S. forces saw the capture of these islands as the first step in controlling the Solomon Islands. It was the first stepping stone to pushing the Japanese army out of their strongholds in the region.

A major target in the Solomons was New Georgia, located 170 miles further north. Because of this, the Russells had an advantageous position - at only 25 miles from Guadalcanal. Furthermore, once in U.S. possession, the Russells offered potential airfields, PT boat bases, and staging areas for future operations. The airfields became particularly important. Finally, the Allies could simply not let the Japanese occupy the islands as they would pose a huge threat to Guadalcanal and American operations to the north. The Marine assault on the Russell Islands was not the grind of Guadalcanal but the airstrips were important to the Allies.

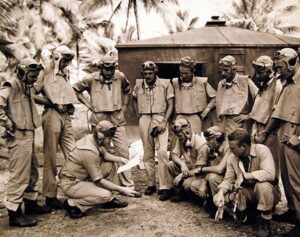

As the air strike efforts were jumping from island to island, providing transport support and other duties, Boyington was still without a squadron or an opportunity to engage Japanese fighters. He seized an opportunity to reconstitute a squadron that had been shut down due to a lack of planes, parts, and pilots. VMF-214 was reconstituted in August 1942 on the island of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, and its 27 pilots came under Pappy Boyington's command for the first time. At 31 years of age (thus known as "Grandpa" or "Pappy"), Boyington's experience made him an unusual and unorthodox commander.

The VMF 214, known as the Black Sheep, got their hands on the Vought F4U F Corsair fighter. This beautiful and swift machine was a pilot's dream. It was fast and responsive and dove well when in a tight spot. The fighter's inverted gull wings gave the aircraft an unmistakably recognizable outline and were designed to provide ground clearance for the massive 13-foot propeller. This cobbled-together squadron, without the normal stateside training, found the Corsair ideal for the situation. Its 2,000 horsepower engine with a top speed of 4,465 MPH made it one of the fastest planes in the Theatre. The Corsairs flown by VMF-214 were seldom flown by the same pilot every day. In fact, in a show of leadership that endeared him to his pilots, Pappy would always fly the plane in the poorest condition on every mission. The Black Sheep is credited with shooting down 97 Japanese aircraft and damaging another 103 during the squadron's two-six week tours of duty, making the Black Sheep one of the highest-scoring flying outfits in the South Pacific at that time.

Boyington wanted to mix it up. He had command and experience that should have resulted in a headquarters billet. Not Pappy.

In fact, he regularly mixed it up with one of his group commanders, Colonel Lard, to the edge of insubordination. Pappy writes about Lard but acknowledges that his book and the TV show used the name "Lard" rather than his real nemesis at the time, Lt. Colonel Joseph Smoak.

The two had crossed paths back at flight school and the hostility intensified over time. Boyington saw Lard as an overweight, bureaucrat, paper pusher. Lard-sized Boyington up as a rule-breaking drunk. At one point, he ordered Pappy not to drink or he would be removed from flying. Once when Lard removed Pappy from company squadron command, General James T. Moore interceded, countermanded the order, and chewed out Lard. Many years later, in 2017, Pappy stated in a History Net interview, "Lt. Col. Joseph Smoak, operations office of Marine Air Group 11 was a real by-the-book Marine, but unlike most of the characteristic backstabbers, he had pulled his time when it counted. He had served in China, and I respected him for that. I was simply the kind of officer he could not understand. I have no ill will toward him or anyone."

Fate put in Pappy's path, good men who kept him between the rails. Men like General "Nuts" Moore, Admiral Halsey, General Chesty Puller, and unnamed Chaplains. Boyington reflects on the conversations with these men and many others in, "Baa Baa Black Sheep." He relates that Chesty Puller told him "there is only a hairline's difference between a Navy Cross and a general court-martial." Pappy was a wildcard but did listen to advice from those that he respected. His respect for Nuts was real and deep. Pappy wrote, "What I appreciated so much was that Nuts Moore told you the problem and then would sit back and listen while you told him how to go about getting it done."

Boyington lived by the leadership principle, "Never send somebody out on a mission that you, as squadron commander, would not go on yourself and always take the first of what promises to be ugly or bad missions." This endeared him to the squadron, but he was constantly at risk. That stress played into the drinking, carousing, and insubordination. But it also led to fast aerial combat pitting Zeros and Pappy against less experienced Japanese pilots. He racked up kill after kill. At times, he worried he would not have another chance to mix it up.

As he approached WWI ace Eddie Rickenbacker's record of 26 kills, the pressure of the media and press to predict when he would get that tie-breaking kill mounted. The original "Fast Eddie," Rickenbacker was the United States' most successful fighter ace in the war and is considered to have received the most awards for valor, including the Medal of Honor, by an American during the First World War. After the war, Rickenbacker was a race car driver.

Fate is a funny thing, and karma is often a bitch. On January 3, 1944, on Bougainville, Major Boyington explains, "I was to lead a fighter sweep over Rabaul, meaning two hundred miles over enemy waters and territory again." With the protection of a wingman, Captain George Ashmum of New York City, Pappy splashed a Zero but in minutes the wingman was shot down. The two had been jumped by about 20 planes. "I could feel the impact of enemy fire against my armor plate, behind my back, like hail on a tin roof. I could see the enemy shots progressing along my wing tips, making patterns" recalled Boyington. His Corsair engine went up in flames with no options, pulling up would direct the flames into the cockpit, and too low to bail out properly, he pulled the eject stick and flew through the canopy. The chute popped but did not have time to open and then he was in the ocean submerging to avoid strafing by the Zeros. As he floated in the ocean, he took inventory of his injuries which included his left ear being almost torn off, shrapnel holes in his arms, shoulder, and left ankle shattered, and a large chunk of left calf muscle missing. He was not thinking of the ace record, but of surviving. He asked himself why a Higher Power would save a bum like him. After 8 hours, he was recovered from the ocean by a submarine. As fate would have it, it was a Japanese submarine.

Five days after Pappy was shot down, the Black Sheep Squadron concluded their second combat tour in the Solomons and the squadron was disbanded. The pilots were assigned to other squadrons and the legend of VMF-214 took on a life of its own. Pappy was assumed to be dead.

Twenty Months as a Prisoner

When retrieved by the submarine, his emergency backpack was collected with his name stenciled on the pack. The Marine aviator ace's reputation preceded him. He was to serve 20 months in two different camps on the mainland of Japan. Like all prisoners in Axis camps, he was starved, tortured, interrogated, and treated inhumanely.

Ofuna Camp

The first camp was in a suburb of Yokohama at a Japanese naval camp known as Ofuna. This camp kept 70-90 "special prisoners" who the Imperial Navy felt had military intelligence that could be extracted. He spent March 1944 until April 1945 at Ofuna. At this secret intimidation camp, the prisoner's names were never revealed to the Red Cross so the family did not know that someone was alive and no communications or packages were received from the Red Cross. It was during this time he was shown a press release telling his story and his receiving the Medal of Honor and that his mother had christened a new carrier. He was pleased to hear about his mother and was shocked when the interrogator said Japan appreciates heroes and offered him a cigarette. There were small acts of kindness along with the brutal conditions that led to a badly healed ankle, beriberi, malnutrition, and losing 80 pounds plummeting his weight to 110.

Over time, Pappy would be tasked with working in the camp kitchen with a civilian cook preparing meals for the guards. This created the opportunity to steal food for himself and other prisoners. Two of the civilian cooks were aware of what was happening and either assisted or turned a blind eye. The additional food helped him and others regain weight, health, and survive.

Omori Camp

The special prisoners were moved out of Ofuna, an intelligence camp, to Omori, a labor camp. Omori prison camp was on an artificial island in Tokyo Bay connected to the main city by a bamboo-slat bridge. This labor camp meted out physical punishment on a daily basis and had some of the most-feared guards in the country.

Other special prisoners at Ofuna and Omori with Pappy included former 1936 Olympic track athlete Louis Zamperini. At the Berlin Olympics, Zamperini was a teammate of Jesse Owens and even met Adolf Hilter. Louie was the subject of the bestselling book and hit movie, "Unbroken." He also struggled after the war and getting back to the United States, but ultimately Louie turned to religion to find peace. He credits his wife with taking him to a Billy Graham revival that opened his heart and allowed him to release the hate and pain he held.

At Omori, days involved picking up or breaking up the rubble in the surrounding Yokohama area. The prisoners were in rags and lacked the strength to efficiently perform such labor-intensive work but falling behind or taking a break resulted in beating and berating from the guards. Boyington always remembered the horrible conditions the regular Japanese who he saw on the streets were in and wrote these civilians treated the prisoners honorably.

It was at Omori that the end of the war started to become clearer to the prisoners. As American B-29 planes flew by, the area was pounded. The prisoners rejoiced in the bombing, which they called "Music" so the guards would not punish the prisoners. As a new airframe, the B-29s had never been seen by the prisoners but caused awe and hope. Even though the end was in sight, it became difficult for some to hang on. The ultimate atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unknown to the Omori prisoners in August 1945. While Omori prison guards tried to explain, it was incomprehensible to the guards and the prisoners. A guard with relatives in Nagasaki tried to explain it, but he did not speak English, and Pappy wrote, "I didn't fully believe it until after the war." The lack of information was a byproduct of being a special captive.

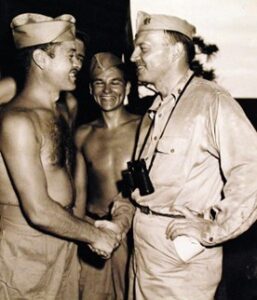

On August 29, 1945, the special prisoners of Omori were released by way of Tokyo. The men were taken to a Tokyo POW Camp (Shinjuku) Tokyo Bay Area 35-140 until September 12th and then flown to Hawaii before being transported back to California. Their health and well-being were of major concern, along with military debriefing and attending to financial and legal matters.

Awards and Declarations

Boyington learned he received the Medal of Honor while in captivity by the Japanese. The nation thought he died when his plane was shot down. After the war in December 1945, Boyington was awarded the Navy Cross, which he considered a "booby prize" presented with a two-minute ceremony.

Navy Cross Citation

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Major Gregory "Pappy" Boyington (MCSN: 0-5254), United States Marine Corps Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer and a Pilot of marine Fighting Squadron TWO HUNDRED FOURTEEN (VMF-214), Marine Air Group ELEVEN (MAG-11), FIRST Marine Aircraft Wing, during action against enemy aerial forces in the New Britain Island Area on 3 January 1944. Climaxing a period of duty conspicuous for exceptional combat achievement, Major Boyington led a formation of Allied planes on a fighter sweep over Rabaul against a vastly superior number of hostile fighters. Diving in a steep run into the climbing Zeros, he made a daring attack, sending one Japanese fighter to destruction in flames. A tenacious and fearless airman under extremely hazardous conditions, Major Boyington succeeded in communicating to those who served with him, the brilliant and effective tactics developed through a careful study of enemy techniques, and led his men into combat with inspiring and courageous determination. His intrepid leadership and gallant fighting spirit reflect the highest credit upon the United States Naval Service.

The words describing Pappy as a "daring," "tenacious," "fearless," and "effective" tactician certainly captures Major Boyington. So would "hard-headed," "stubborn," "daredevil," and "drunk"; but as said at the outset in polite society one should ignore faults and flaws and only recognize heroism.

Medal of Honor Citation

For extraordinary heroism above and beyond the call of duty as Commanding Officer of Marine Fighting Squadron TWO FOURTEEN in action against enemy Japanese forces in Central Solomons Area from September 12, 1943, to January 3, 1944. Consistently outnumbered throughout successive hazardous flights over heavily defended hostile territory, Major Boyington struck at the enemy with daring and courageous persistence, leading his squadron into combat with devastating results to Japanese shipping, shore installations, and aerial forces. Resolute in his efforts to inflict crippling damage on the enemy, Major BOYINGTON led a formation of twenty-four fighters over Kahili on October 17, and persistently circling the airdome where sixty hostile aircraft were grounded, boldly challenged the Japanese to send up planes. Under his brilliant command, our fighters shot down twenty enemy craft in the ensuing action without the loss of a single ship. A superb airman and determined fighter against overwhelming odds, Major Boyington personally destroyed 26 of the many Japanese planes shot down by his squadron and by his forceful leadership developed the combat readiness in his command which was a distinctive factor in the Allied aerial achievements in this vitally strategic area.

The following day the Medal of Honor, which had been first issued posthumously by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was presented by then-President Harry S. Truman. He felt the Medal of Honor ceremony with other recipients was appropriately solemn and dignified. President Truman stated, "I would rather have this honor than be President of the United States."

Truman had served in the Missouri National Guard and in World War I, had been sent to France with an artillery unit. Pappy probably did not know that Truman at the end of WWI told his unit, "Right now, I'm where I want to be - in command of this battery. I'd rather be here than the President of the United States."

Final Years in the Military

His faults and flaws were in remission for a while. He recognized that capture prevented him from drinking and that was a terrific benefit to him both mentally and physically. He had every stated intention to stay sober.

In the Honolulu stopover, Pappy once again met up with Major General Nuts Moore who tried to give him good advice about post-war fame and challenges. Moore was ending his career and had civilian opportunities. Boyington was thinking he was staying in the Corps, but because of his physical condition and the fact he had been out of operations for over two years, his military future had an expiration date on it, even if he did not know it.

A war bond tour for the Marines did occur, as Medal of Honor recipients were often put on a parade. These month-long bond tours always became boring, tedious, and stressful. As he tried to envision a future, he had to again deal with financial hardships. Prior to the war, he placed his service pay in a trust for his children. He entrusted a female friend, a "drinking gal," to manage it, only to learn upon return that it was not done well. Neither he nor the children were getting all the money due. He should have known you could not trust the promises of a drunk.

As a Medal of Honor recipient, Lt. Col. Gregory Boyington was in-demand for parades, speaking engagements, and meet and greets. With that demand came all the trappings of instant and temporary celebrity. There is a long list of MOH recipients that find the stress of such celebrity status to result in alcoholism and bankruptcy. Pappy had brushes with both prior to his celebrity status and was pulled back into the bottle by the Medal of Honor fame.

The expiration of his military career came before he expected it. The Medical Board, probably prompted by enemies from within the Corps, scheduled a review of his physical condition to continue to serve. The combat injuries and the POW-caused medical conditions certainly provided good grounds for his ultimate medical retirement. He was promoted to "bird' or full Colonel prior to his medical retirement in August 1947. This was a graceful end to the military career of a Medal of Honor recipient and WWII ace that was always precarious at best.

Final Four Decades

One lesson learned from those awarded the Medal of Honor, and life in the Marine Corps is that life goes on for the living long past the fleeting time when valor and heroism are demanded and Semper Fi is the daily motto.

Back in the civilian world at age 35, this hero had to face the most frightening enemies of all, his faults and flaws. His story is not the happy ending of Louie Zamperini who found God and a purpose in Christian ministry focused on at-risk youth, which he had been. Louie received the Distinguished Flying Cross but did not carry the burden of alcoholism or multiple marriages during his 97 years of life.

Financial issues would haunt Boyington constantly. He held various sales and marketing jobs, each for a few years. Companies attracted to him were often financially flawed themselves hoping his fame would make the difference. His well-known drinking exploits had him representing a brewery for a while. A drunk should not own a bar or advertise for a brewery, but he had to make a living.

For many years, he refereed "professional" wrestling matches in California and surrounding areas. His fame was promoted, the adulation of the crowds was stimulating, being around the brawling felt natural, the money was easy and he could do the job while stinking drunk.

Another fault or flaw he returned home to was the revolving marriages that cost him money and energy. Upon returning to the states, he married for the second time in 1946 to a 32-year-old woman. He married for a third time at age 47 to a 33-year-old woman. At age 66, he married a fourth and final time in 1978 to Josephine Wilson, then 51 years of age, which lasted 10 years until his death in 1988 from terminal cancer. She lived for another four years, dying at the age of 62. One can only hope somewhere along that martial road Pappy found true love or something that resembled it. While talking about press celebrity, but it seems true of his personal life, Boyington wrote: "For all this was not sufficient for a man who just wanted to be wanted, and for some reason, or another had felt that he never had been since childhood."

Pappy had been a favorite target of the press in the late 1940s and 50s because of his many faults, flaws, and marriages. But over time he fell out of regular negative press coverage and his image was burnished in the 1970s with the television release of Baa Baa Black Sheep. It helped tremendously that handsome and popular actor Robert Conrad played Boyington. Conrad found rating success from 1976 to 1978 as legendary tough-guy World War II fighter-ace Pappy Boyington in "Baa Baa Black Sheep", which is still in regular rotation on cable TV. The show's success led Conrad to win a People's Choice Award for Favorite Male Actor and a Golden Globe nomination for his performance. For a man that craved to be wanted, that had to feel somewhat like vindication to Boyington, even if he criticized the show for its lack of authenticity and "Hollywood hokum."

Pappy had been a favorite target of the press in the late 1940s and 50s because of his many faults, flaws, and marriages. But over time he fell out of regular negative press coverage and his image was burnished in the 1970s with the television release of Baa Baa Black Sheep. It helped tremendously that handsome and popular actor Robert Conrad played Boyington. Conrad found rating success from 1976 to 1978 as legendary tough-guy World War II fighter-ace Pappy Boyington in "Baa Baa Black Sheep", which is still in regular rotation on cable TV. The show's success led Conrad to win a People's Choice Award for Favorite Male Actor and a Golden Globe nomination for his performance. For a man that craved to be wanted, that had to feel somewhat like vindication to Boyington, even if he criticized the show for its lack of authenticity and "Hollywood hokum."

A decade after the television show, Pappy's health finally caught up with him. He developed terminal cancer and died in January 1988. His fourth wife was with him during hospice and at the end. He had seen one child commit suicide, but his son graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1960 and retired from the U.S. Air Force as a Lieutenant Colonel. Boyington had many things to be proud of and many things to regret.

Colonel Gregory "Pappy" Boyington's life provides both inspiration and a cautionary tale. Greatness can be accomplished by those with faults and flaws. Overcoming those faults takes greatness. Friends and allies will often provide good advice that may be hard to hear and harder to live by. Only you can come to peace and understand that you are wanted.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED