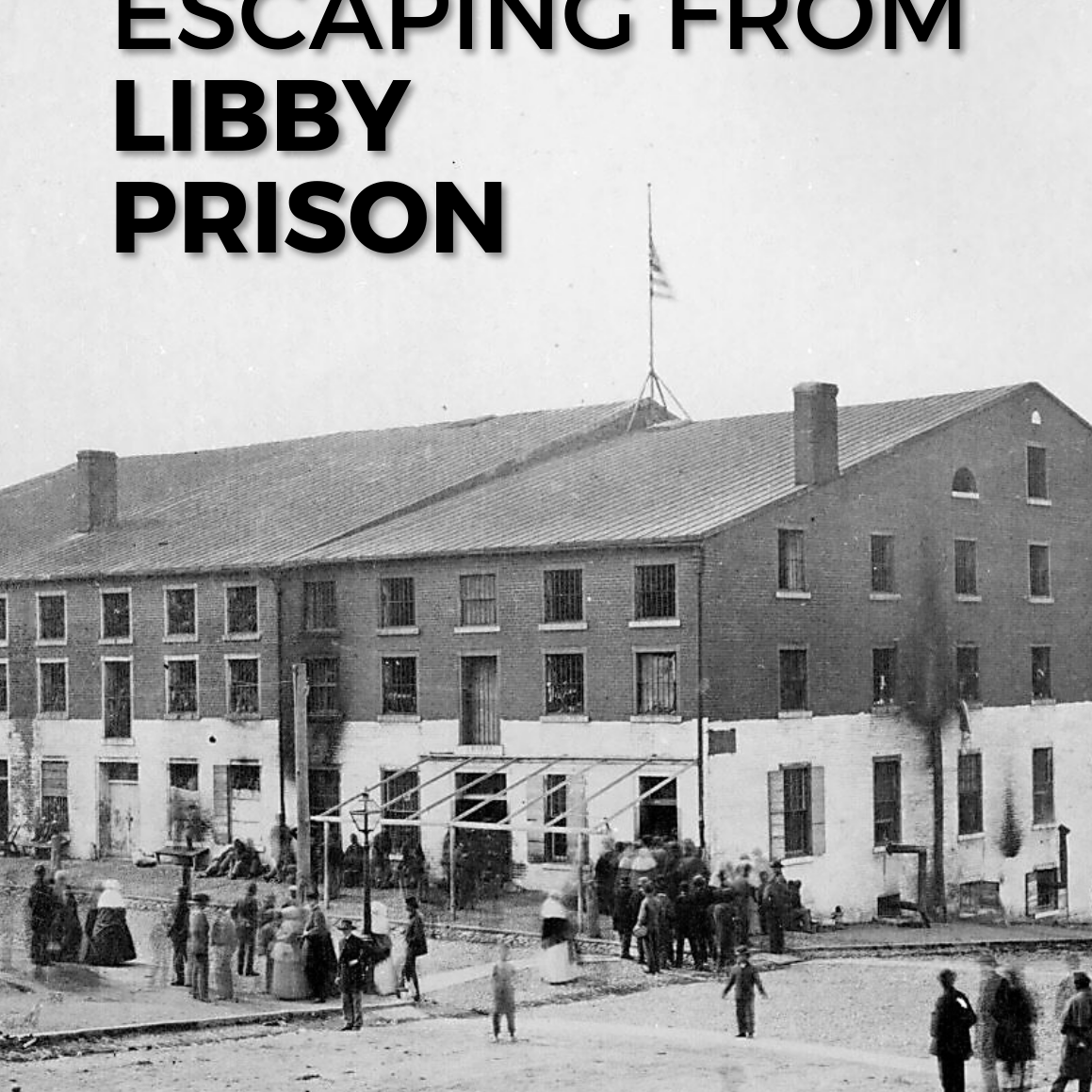

Escaping from Libby Prison

By James G. Fausone, Esq.

The desire to escape capture is a response as old as humankind. Stories of escape from prison and captivity are found in the Bible; such as Peter's escape from King Herrod. Greek mythology has numerous stories of escape from captivity including Prometheus and Persephone, the sweet daughter of goddess Demeter who was kidnapped by Hades and later became the Queen of the Underworld. Therefore, it is simply human nature to plan and dream of escaping if you are a prisoner of war.

This was true during the American Civil War. This was a conflict among states, families, and siblings. This brutal war for America centered around slavery, it's estimated that 620,000 soldiers died between 1861-1865. Waging war in such close geographic quarters, using the military techniques of the day, it is estimated 400,000 Union and Confederate POWs were held in 150 different prison sites. This story is about the escape at one Confederate prison in particular - Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia.

Libby Prison

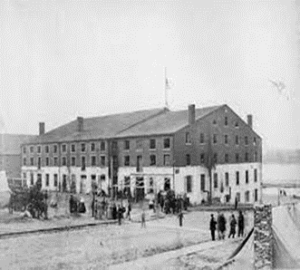

The Libby Prison complex began as a tobacco warehouse in Richmond, Virginia. It was a large brick complex with multiple floors and basements.

James Libby, a Virginia businessman, built the five-story warehouse in 1855. What began as the "Libby & Ryland Tobacco Warehouse" was designed by architect Alexander Parris. It served as a storage and processing facility for tobacco, a major commodity in Richmond. The warehouse was appropriated by the Confederacy for prison-use and rented from him for $100/year.

The legacy of the property would be associated with its use as a prison. It became notorious for its harsh conditions, overcrowding, and lack of sanitation. The cramped quarters, inadequate food and medical care, and rampant disease led to suffering and death among the prisoners.

After the war, the building was removed brick-by-brick and shipped to Chicago for a war museum, which ultimately closed after eight years and was torn down. The bricks were sold as ghoulish souvenirs at the time.

The Context

The Civil War was originally intended to be resolved quickly; it did not go that way. In fact, the stubbornness of the South and North surprised many. The call for troops was answered on both sides of the split by amazing numbers. Young men from Michigan, Ohio, and New England found themselves marching south to a portion of the country they did not know.

The high number of casualties and captives caught each military command off-guard. In July 1861, after the First Battle of Manassas (known as the Battle at Bull Run in the North), the former tobacco warehouse was utilized as a prison holding captured Union officers. This battle resulted in 1,312 captured or missing Union troops. Officers were sent to Libby Prison and enlisted men to a nearby island prison.

As the war dragged on and more prisoners were captured, there was a growing need on both sides for housing, food, and medicine. Neither military command could handle the mass number of captives in their custody. As the South became more trade-isolated, caring for the population became problematic, with the captives suffering even more.

This was a time when no Geneva Convention existed or even knew how to handle prisoners. However, humanity required basic needs in exchange for prisoners. For example, surgeons and chaplains were easily exchanged between both sides. Rules were developed for other exchanges of prisoners, those with connections, officers, etc. Their dilemma was whether exchanged prisoners would seek retaliation for the miserable conditions they endured. It's reported that the Confederate soldiers were better treated, fed, and cared for, than the Union POWs. These exchanges were irregular and stopped for long periods when political or public relations disputes arose. Prisoners could not hope to be in an exchange, or may not even live to see the next round. The fleeting hope for inclusion in an exchange was not strong enough to prevent the Libby prisoners from looking for an escape route. Some escapes were as simple as dressing like a Confederate soldier and walking out the main gate. The rag-tag uniforms made this possible, but highly unlikely.

The Big Plan

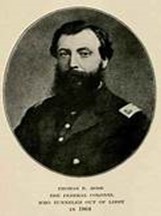

Boredom is one of the main features of captivity. A man has to find something to do to make the endless hours pass from sunrise to sunset. Naturally, the men engaged in games, lectures, music, and any other distraction they could dream up with limited resources. Some men spent their time thinking about how to escape. Thomas Ellwood Rose was one of those men and Alexander Campbell Hamilton was a kindred spirit.

Thomas Ellwood Rose was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, studied law and was a teacher before the Civil War. He enlisted in the Union Army in 1861 and quickly rose through the ranks, becoming Colonel of the 77th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment in 1862. Rose led his regiment with distinction throughout the war, participating in major campaigns like Antietam (September 1862), Fredericksburg (December 1862), and Gettysburg (July 1863).

Rose commanded the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment who participated in the Chickamauga campaign (September 1863). After being captured in battle, he was detained at Libby Prison. That fall and winter, Rose conjured a plan that would result in the ultimate escape in February 1864.

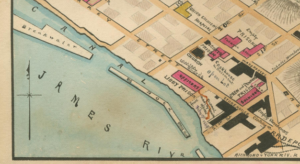

Any escape begins with formulating a plan, executing the groundwork for the escape, the day of the escape and the aftermath of the scape. Rose was particularly good at dreaming up a plan and executing it. He was not the highest-ranking officer in the prison nor one likely to be in an exchange. As he pondered a way out of the rat-infested prison, Rose noted how close the building was to the river. He knew that there must be a large sewer that connected the buildings to the outside and into the James River. By mid-November 1863, Rose had convinced himself and fellow prisoner and officer, Major Alexander Campbell Hamilton, that digging a tunnel from the basement of the building to the outside sewer system was worth attempting.

Who Was Hamilton

Andrew Graff Hamilton was Rose's close confidante and second-in-command during the tunnel planning and digging. Hamilton played a vital role in recruiting allies, managing tunnel work schedules, and maintaining morale among the prisoners. Hamilton was born in Wisconsin Territory (present-day Minnesota) in 1817. He graduated from West Point in 1841 and served in the U.S. Army before the Civil War. He distinguished himself in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican-American War, rising to the rank of Captain by 1861. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Hamilton joined the Union Army and was eventually promoted to Major of the 3rd Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Like Rose, Hamilton was captured at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863 and imprisoned in Libby Prison. Hamilton played a key role in the escape plan, assisting Rose with meticulous calculations and ensuring the tunnel reached the correct destination outside the prison walls.

While Rose is often credited as the mastermind, Hamilton's contributions were indispensable to the success of the escape. When he escaped on February 9, 1864, he did not reach Union lines. He was recapture,d and eventually did escape from Libby Prison and rejoined the Union Army. Hamilton was the guest of honor at Libby Prison National War Museum, at the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. He was murdered on April 2, 1895 by Sam Spencer in Morgantown and is buried in the Bethlehem Cemetery in Reedyville, Kentucky. Dedicated June 15, 2013.

The Big Dig

Digging a tunnel to escape certainly seemed delusional for there were no tools to excavate such a tunnel and the risks were enormous from discovery and collapse. Over time the idea became the central focus of Rose, Hamilton, and others. The logistics for these non-civil engineers were considerable. There was no map of where the sewers ran. No one had any survey tools to keep straight lines during the tunneling, either. The further the tunnel progressed, the less oxygen was available below ground. Tunneling required laying in the mud and muck, which was the home turf of ubiquitous rats. The digging tools were fashioned from spoons, knives, and a broken shovel. The dirt that was excavated had to be removed and disposed of so as not to catch the eye of Confederate guards.

Tunneling required Rose and Hamilton to work at night in the prison basement. It was divided into three segments from its warehouse days when keeping different tenants' goods separated was important. The basement areas served as kitchens and storage when the prison was full. It was too dark, dank, and infested for regular use by the prisoners or guards. There would be four attempts to tunnel out.

The first attempt at penetrating the walls and into the outside prison was successful but ill-advised. This first attempt proved it could be done, but the short first tunnel that just opened up on prison grounds was a no-go. The open grounds were patrolled, and any movement was easily discernible. As Rose poked his torso above the ground, he saw the guard. As he got back inside the building, the guards apparently thought he was a civilian contractor sleeping in the building.

A second attempt was foiled by guards in the prison that continued to patrol and made the escape route ill-advised. By this point, some 400 men knew of the plan. They were sworn to secrecy, but Rose and Hamilton abandoned the plan as too many concerns of safety and security existed.

One of the challenges was to find a way into the basement that did not attract the guards. The idea became tunneling from behind the kitchen fireplace into the east cellar, which would be hidden from the guards. It took 11 days to scrape away at the fireplace bricks and break into the east cellar. A chute into the basement was created so that men could wiggle themselves through. Rose was the main tunneller and learned that a rope tied to his legs allowed Hamilton to signal him and even pull him out when too exhausted or overcome with lack of oxygen.

With limited success, each failed attempt was a learning experience. Rose and Hamilton believed they could tunnel from the basement into a small sewer that would connect to a larger sewer from which to escape. The digging began in earnest with teams working from 9:00 p.m. to 4:00 a.m. in shifts. This work was conducted with the constant fear of spies or traitors among the prisoners.

It is not surprising that with no instruments to guide the digging and just intuition, this third attempt was ill-fated as water poured in suggesting the angle was on too steep of a downward slope. In another attempt in the same direction, the angle was on an upward slope causing a cave-in under a heavy outside brick furnace. The guards, noticing the cave-in, believed rats had undermined the soil beneath the old furnace.

Rose and Hamilton were depressed but determined to make an escape route. In early February 1964, a rumor spread that the Confederates were going to move 13,000 Libby prisoners further south as the Union was pressing attacks on Richmond. They thought if Union troops made a lightning raid on the capital of Richmond they could capture President Jefferson Davis, the Confederate cabinet, and end the war.

All Libby prisoners knew that if they moved south to another prison, it would be even harder to escape and if they did, it would be a longer trek to Union forces. This added fire in the men to find a way out. One of the alternative prisons was the infamous Andersonville Prison, which was a 16-acre site between Plains and Americus, Georgia. The area was to become famous, 113 years later, as the hometown of the Navy Veteran and 39th President of the United States, James (Jimmy) Earl Carter, Jr.

4th Tunnel & Escape

Rose and the team believed in, "If at first you don't succeed, try, try, try, try again." Each failure taught them something to be used in the next tunneling effort. Author Joseph Wheelan discusses at length these efforts in, "Libby Prison Breakout: The Daring Escape from the Notorious Civil War Prison." The team's focus had to be accomplishing the task, not its enormity. A good 50-feet had to be excavated, one tiny spoonful of soil at a time. Progress was measured in half inches. The frozen ground yielded to the constant scraping and digging ever so slowly.

The tunnel was 24" x 18" x 16" wide. It took 17 days to excavate the fourth tunnel. By that point, the Rose team had been digging tunnels at night for 53 days. Failure was so close that the fourth tunnel was opened up and to the disgust of Rose, he popped up to find the tunnel was short of the prison fence. Heartbroken, the tunnel exit was plugged and digging continued. The next attempt would put the tunnel outside the prison fence.

Rose got out and was on Canal Street. He had to be torn whether to return to prison or simply continue to walk to freedom. Rose, having a moral compass, went back into the tunnel and into Libby Prison. The team was excited. After discussion, it was agreed to wait one night before escaping. The risk of discovery was great and the fear of being turned in was real.

No one could sleep or eat in anticipation of nightfall on February 9 into the morning of February 10, 1864. The team deliberated on how to execute the escape on this 30-degree winter night. Men would be sent into the tunnels in groups of 15. There was little space and time allotted for the men to exit the tunnel and walk away without raising suspicions. For over 5.5 hours there was a steady stream of beleaguered men crawling away from captivity. By agreement, at about 3:30 a.m., the entrance to the tunnel was rebricked. One hundred nine men used the tunnel that night. Majors and colonels numbered 21; the escaping captains were 35 and the lieutenants were 53. The men quickly scattered in small groups each of which had discussed, "What next?" Some of the groups headed for the countryside. Some of the groups had decided to stay in Richmond with the help of sympathizers such as Elizabeth VanLew, a well-known Richmond socialite and northern sympathizer. In 'Libby Prison Breakout", Wheelan recounts stories of the escapees bumping into Confederates that first night and barely escaping, or telling fantastic tales of near misses.

All the escapees knew they had hours to get to safety, in whatever fashion that was defined. As sunrise occurred on February 10th, the prison guards realized the morning headcount was significantly off. This naturally led to an all-out effort to uncover the means of escape and by late afternoon the tunnel entrance was uncovered by the guards and no further escapes were made through the fourth tunnel.

As reprisals were being handed out in Libby, the Confederate soldiers were scouring Richmond and the countryside to hunt down the 109 escapees. Recalling that the men were malnourished and not clothed for the weather, running was not a realistic option. The odds were in favor of the hunters. By the end of February 11th, 22 of the escapees had been recaptured. The Confederates were concerned about the information the Union officers could give about the security of Richmond. In the end, two men drowned trying to escape and 48 were ultimately recaptured. The organizer of the effort, Rose and Hamilton, were both recaptured. Rose was caught on Day 5 and spent 38 days in isolation as punishment.

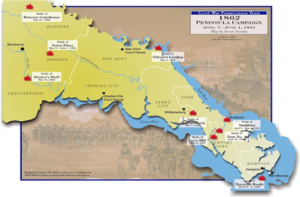

There were 59 that did escape and made it back to Union lines. The first men made it to Williamsburg, southeast of Richmond, after 5 days. As the crow flies, the distance between Richmond (Libby Prison) and Williamsburg is approximately 55 miles. However, escaping prisoners could not have followed a straight path. Navigating wooded areas, rivers, and potentially Confederate patrols would likely have made the journey significantly longer, possibly 75-100 miles.

The terrain included rolling hills, forests, farmland, swamp land, and the James River, presenting diverse challenges in terms of navigation, obstacles, and potential exposure. Escapees from Libby Prison were typically malnourished and weakened from their imprisonment. This, coupled with the physical demands of traveling long distances on foot through difficult terrain, would have severely tested their endurance. Lack of adequate food and water would have been a constant concern, forcing them to scavenge for sustenance or risk encounters with civilians or Confederate patrols. Navigating without maps or proper guidance would have increased the risk of getting lost or disoriented, potentially leading them deeper into enemy territory. The constant threat of discovery added another layer of danger, necessitating stealth and vigilance throughout the journey. Weather conditions could have further exacerbated the difficulty, as this was winter in the south. The success of reaching Williamsburg depended on a combination of factors, including physical resilience, resourcefulness, luck, and assistance from Union sympathizers or escaped enslaved individuals familiar with the terrain.

Beyond the Libby Prison Escape: Boosted Union Morale

After years of Union defeats, the successful escape of over 100 Union officers served as a major morale booster for the North. It showcased the indomitable spirit of the prisoners and demonstrated their unwavering determination to regain freedom. This fueled a renewed hope and resilience within the Union ranks. The escape exposed glaring security vulnerabilities within Libby Prison and the broader Confederate prisoner management system. It highlighted inadequacies in infrastructure, guard vigilance, and intelligence gathering, prompting the Confederacy to tighten security measures and reevaluate its prisoner policies. The escape garnered attention across the nation, drawing public attention to the harsh conditions endured by Union prisoners of war. The audacity of the escape and the plight of the captured officers generated sympathy and criticism towards the Confederacy's treatment of POWs, potentially influencing public opinion and war sentiment. The escape transcended its immediate success and became a powerful symbol of defiance and resistance against Confederate authority. It represented the unwavering commitment of Union soldiers to their cause and their refusal to be cowed by captivity. This spirit of resistance resonated with the larger struggle for freedom and abolition during the Civil War.

Impact on Prison Management

The Libby Prison escape serves as a cautionary tale for both sides, contributing to the evolution of POW treatment during the Civil War and beyond. It emphasized the importance of humane conditions, proper infrastructure, responsible management of POW camps, and influencing future policies and regulations. Beyond its historical context, the escape continues to inspire for its display of remarkable ingenuity, teamwork, and unwavering determination under dire circumstances. It serves as a reminder of the human capacity for overcoming seemingly insurmountable challenges and the power of collective effort in achieving seemingly impossible goals.

Life After Libby

Libby Prison was symbolic of the hardship and depravations of war. As mentioned earlier, the building was moved to Chicago and was a museum for a short period.

After escaping, Rose continued to serve in the Union Army until the end of the war, earning a brevet promotion to Brigadier General for his gallantry and leadership. Despite being mustered out with the 77th Pennsylvania on December 5, 1865, Rose re-enlisted in the United States Army on July 28, 1866, as a Captain of the 11th Infantry Regiment. Rose was brevetted Major and Lieutenant General on March 2, 1867, before retiring on April 23, 1894.

During the last 13 years of his life, Rose lived a relatively quiet life, residing in various locations and holding different positions between 1894 and 1907. He lived primarily in Washington, D.C., residing at different addresses throughout the city, with some time spent in Philadelphia and Bucks County, Pennsylvania, near his hometown.

Rose's primary occupation during this period appears to have been related to veterans' affairs. He served as a Special Examiner for the Pension Bureau of the Department of the Interior. This role involved investigating and adjudicating pension claims filed by veterans and their dependents. Additionally, he held leadership positions in various veterans' organizations, including serving as Commander of the District of Columbia Department of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a prominent fraternal organization for Union veterans. Rose died in Washington, D.C., on November 6, 1907, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Lydia C. Trumbower Rose (1831-1922) is buried with him.

While the 109 men who escaped Libby Prison may have been forgotten, the spirit they embodied remains in the soul of every American soldier who has been captured and who dreams/schemes of a way to escape.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED