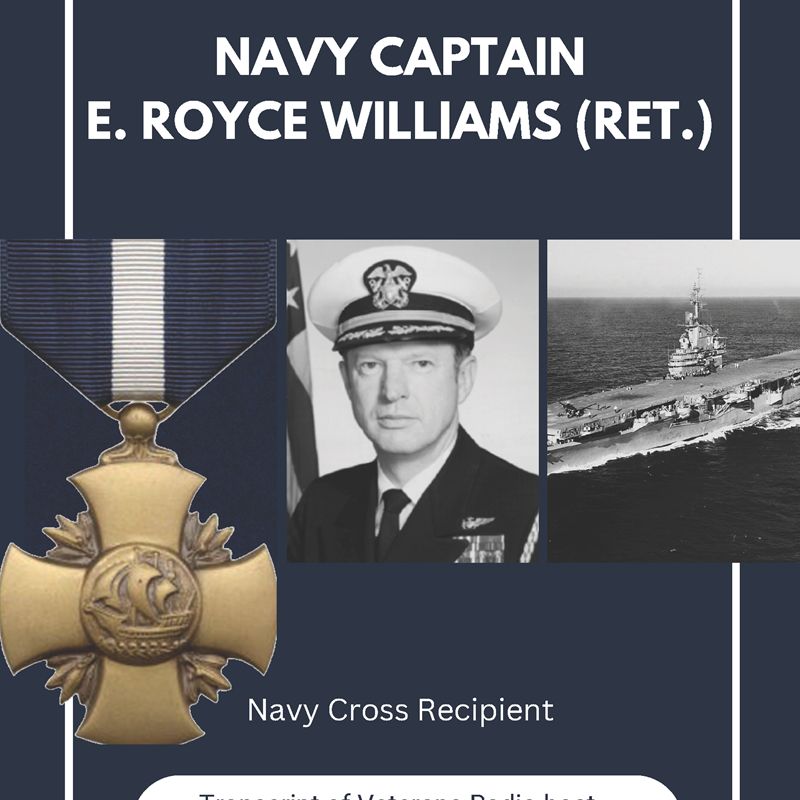

Elmer Royce Williams

Captain, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

Transcript of Veterans Radio Host Jim Fausone's Interview with Navy Cross Recipient Capt. Elmer Royce Williams (March 21, 2023)

VIEW ELMER ROYCE WILLIAMS' NAVY CROSS CITATION!

James G. Fausone: We want to welcome to Veterans Radio today Navy Captain (ret.) E. Royce Williams. Royce, welcome to Veterans Radio.

E. Royce Williams: Thank you very much. I'm pleased to be here.

Fausone: Royce has been retired for a long time. He’s currently a 97-year-old California resident, and he is back in the news because he recently was awarded the Navy Cross for certain combat valor in Korea back in 1952, of all times.

Let's start here though Royce, how did a nice kid like you from Wilmot, South Dakota end up in the Navy for a career? I always get a kick out of these guys who live in states where there isn't an ocean anywhere nearby, but they go into the Navy and stay for a career.

Williams: I supposed I was enticed by a movie, but I had an early flight in an airplane when I was four. I had a relative flying out of Fargo, North Dakota for the weather service who did amazing things with open cockpit biplanes back in that day going to extreme altitudes for the equipment he had - 32,000 feet or such - without communication and instrumentation. Sometimes, he would be above the clouds and then have to search for blue sky somewhere to get back down, often leaving him in Canada. My brother and I both started early on thinking about what next, some years hence, and carrier aviation was a large part of the goal.

Fausone: It was certainly brand new at that time. It took nerves of steel to fly at that point. Was that a family trait, as well?

Williams: My dad was World War I, and one tremendous guy. My early ventures were just kind of like a young wild man running around, damming up a creek to make a swimming pond, building wikiups, and fighting with swords following the Crusade movie. I had a lot of excitement fun and freedom.

Fausone: You were looking for adventure and you certainly found it in the Navy. As I said, he's a retired Captain, so he retired after 70 missions in Korea and 110 missions in Vietnam. So, plenty of miles and hours logged there, Captain Royce Williams.

Williams: I don't know if that adds up properly. I think my total combat missions were 227.

Fausone: OK, great! That's even better to get the record correct. Let’s talk about the dogfight in Korea that kind of brought this back to attention after it was kept confidential for so many years. Tell us about this dogfight in North Korea with what, I think, was seven Soviet fighters and you shot down four of them ultimately.

Williams: Yes. We were rather new amongst the carriers to arrive in the Korean War. The Navy pretty much owned the eastern half of North Korea. It extended all the way to the Yalu River, which was the border between China and Korea North, and also a portion of it Soviet Union and North Korea. Some of the juicier targets were a little bit out of our range and deserved to be hit to carry out our responsibility.

Admiral Jocko Clark, who was on the Missouri, designed the mission that we were on. The morning of the 2nd of November in 1952, we arrived at Chongjin, a major city in North Korea about 100 miles south of Vladivostok, Soviet Union. Being at that location permitted us to hit targets otherwise left pretty much alone. I was on the first mission of the day in good weather and conducted a strike against manufacturing and warehousing in Hoeryong City pretty much right on the Yalu River across from the Soviet Union, followed by strikes from two other carriers. I was in the near wing on the Oriskany, but we also had two other ship carriers, plus maybe 20 escort ships, including the battleship Missouri.

We had a cruiser, the Helena, whose first mission for the NSA was with a team of experts in radar and communications with Russian-speaking personnel. This strike, for all three carriers, was pretty disturbing to the Soviet Union. We were close by, bombing targets and they got rattled and launched a lot of airplanes. There was a lot of chatter of communications going on. I arrived back from that attack and was notified to get a quick lunch and come back because I was going on the next combat Air Patrol.

Fausone: You’re a 27-year-old pilot at that point, right? Flying into that space was relatively new. Talk to people about the jet that you were flying which today most folks wouldn't even know the know the name of.

Williams: I was flying the latest in carrier jet aviation for the Navy carriers, it was an F9F-5 Panther. It had the capability of carrying external weaponry, bombs rockets, etc. It had internal guns of 420-millimeter in the nose of the airplane. As such, we could seek a variety of targets and though we had an air-to-air capability, our assignment was primarily air-to-ground of trucks and trains and any type of logistic problem -- bridges and train tracks and also close air support for our troops on the ground.

Fausone: That’s what makes this dogfight with the MiGs so interesting in many regards. As you say, the Soviet Union wasn't really happy with you guys flying that close on the first mission and striking some things. Then we get into the second mission and they decide they're not going to let you go undisturbed. Tell us about that.

Williams: You're correct. We were not at war with the Soviet Union. We did not expect any threat to come out of this strike against North Korea, but on the other side of the river, people were making up their minds evidently not let the United States get away with this. I didn't expect any type of actual engagement on my combat air patrol mission.

We were launched, and by this time bad weather had moved in, and we were facing a blizzard. The ship was bouncing around quite a bit and there was a low ceiling of clouds. We launched and rendezvoused under 400 feet and then went climbing through the clouds with our direction and altitude control by our combat information center aboard the Oriskany in this climb through the clouds to on top of them at 12,000 feet, we were advised of inbound Bogies, meaning unidentified airplanes, headed toward the task force. We were aware of that while climbing, and once on top and in the clear, we could see seven contrails headed directly at us. These were coming directly out of the Vladivostok area, which was not very far away from us.

Fausone: We’re talking to Captain Royce Williams, who recently was awarded the Navy Star for this upcoming dogfight. These seven Soviet MiG 15 fighter jets are coming your way. You start out with four planes in your squad, two have to turn back because of some mechanical problems, and you and a wingman now have yourself faced with Soviet MiGs. Tell us a little bit about their maneuverability and air-to-air capability as compared to what you're flying in the Panther.

Williams: At this time in history, this was the world's best fighter airplane. I had a great airplane in that it was Grumman and tough built with good capabilities, within the limits not to match the MiGs in aerial combat. We didn't really expect to be combating them, but as it turned out they chose to fight and it happened.

Fausone: You and your wingman were in that fight. I think I've read it was about a 30-minute dogfight. Tell us what went on and what's going on in your mind at that point.

Williams: These contrails flew over us. They were at extreme altitudes, I would guess 50,000 feet at least. Once they passed over us, they turned back North and I thought probably heading home. I assumed they were Soviets out of Vladivostok. I was instructed to climb and to intercept, if possible if it came to that, but to be ready. I immediately charged and fired my guns so that all my fighting capability was ready to go, and my wingman and I climbed keeping them in sight.

We got to 26,000 feet and they were by this time about halfway between us and Vladivostok and they split into two groups and dived out of the contrails. I thought they were probably going to go into land, but I was wrong. And in short order, saw four of them in loose formation attacking me and all of them firing.

Fausone: From the carrier, as I understand it, the original thought was to have the Navy Jets protect the US warships. The commanders on the carrier thought “Don't engage, the Soviets aren't going to engage.” But, all that thinking down on the on the ship was wrong, wasn't it?

Williams: Entirely correct, yes. I didn't expect them. I saw the airplanes and once they flew over and I saw they were MiGs, I knew they were not friendly. I was prepared for what eventually happened, but I didn't expect it. When they came in shooting, I knew I could not, should not, run away.

I maneuvered rather hard and ended up in firing range on the tail of the number four airplane in that group of four. The other three were coming in from the other direction, so seven were in the fight. I just fired a short burst of 20-millimeter at four and it started smoking and dropped out of formation.

At that point, my wingman chose to follow him instead of sticking with me. I continued to trail the remaining three as they climbed abruptly, amazingly with ease well above me, and reversed to come back and fire at me. While that was happening, I was going to fire at the number three guy that just lost his wingman.

I saw the other two -- the lead of the whole flight of seven -- heading directly in and firing. I trained my weapon system on them and when I thought they were in range, I fired a short burst and that airplane stopped firing, did a turn off to the left while I was noticing his wingman now in and shooting at me. I trained my guns on him and a short burst, he quit firing and did maneuver and slid right underneath me, indicating to me that he was probably dead.

Fausone: As you reflect back on this Captain Williams, how much of this do you attribute to training, good luck, good equipment or the grace of God?

Williams: Well, put the influence of God number one. I was trained for this sort of thing in that we were going to war and our mission was primarily the support of our troops on the ground. We did very little in the way of training for air to air combat, but I had always had an interest in this and on my own with my wingman did do some practice.

Fausone: As this event unfolded, Royce, over the 30 minutes or so, I believe I've read you used up all the ammunition you had.

Williams: That's right.

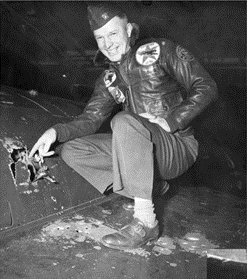

Fausone: So this ended at the right time because you were getting out of ammunition. You took on a lot of shots. Your plane had something like 263 holes in it when it finally got back to the ship, does that sound about right?

Williams: Yes. My plane captain went out with a grease pencil and circled each one and counted them and that 263 is the number he reported.

Fausone: Captain Williams here used all 760 rounds of his 20-millimeter cannon shells on his airplane. Again, with the grace of God, training and good equipment came out on the positive side of that. But it wasn't over yet, you had to get back to the carrier. That was a little harrying as well it sounds like.

Williams: I realized that this fight took 35 minutes. A usual air-to-air fight is seconds or maybe a few minutes at most, and never one airplane against being so outnumbered. So this was a different type of thing. I was there for a long time and I fired only when I had a gun solution in range, so I wasn't wasting anything. I ran out of ammunition when I had an airplane smoking and it was descending and not maneuvering. I think that eventually the plane that the pilot ejected from was not recovered in time to save his life.

Fausone: Before I get to the confidentiality of this dogfight, go back and tell us about trying to get this back on the carrier because of fuel and holes in it and decreasing weather conditions. Tell us about that, because quite frankly I can't imagine landing on a carrier.

Williams: The MiG that hit me with a 23 -23-millimeter exploded in the accessory section of the engine and destroyed the hydraulics. It put the airplane pretty much on a rig and severed the cables to the rudder, so I was left primarily with an elevator which gives you the capability of going up and down, that's very limited as far as turn.

After I was hit, I happened to be pointed in the direction of the task force and the clouds that were delivering the blizzard. This fight took place in clear air. I headed for that and the guy settled right behind me at perfect range to shoot me out of the sky, and I jammed the stick using my available elevators which did work. I would zoom up and then down, doing it as drastically as I could, which caused the guy to put a bunch of bullets over me, then under me, and then over me. I just kept dodging got lucky, and gave credit to God. I had reached the clouds -- they were very dense -- and I got in there and we lost sight of each other. My attention now came to thinking about how I was going to get back aboard a carrier.

Fausone: That wasn't easily done in this situation. It took both your skill and the carrier Captain’s skill to get you lined up, because you didn't have all the normal controls you would have had for an aircraft carrier landing.

Williams: Exactly right. I knew where the bottoms of the clouds were, so I carefully on my own descended under instrument conditions. I gave up the idea of parachuting because I wouldn't be rescued in time to save my life under the ocean conditions. I arrived and came in sight of the task force and they were at general quarters. That means, those who are in the perimeter and have anti-aircraft capability, are free to shoot at anything unidentified if they feel it's a threat. I hadn't been coordinated to where they knew I was friendly, and unfortunately, our ships fired at me. My commanding officer had just been launched to be my relief and engage if it were to happen. It didn't happen, but that was the idea -- he saw what was going on and he got him to cancel firing.

Then I just worked on studying my problem, seeing what I would have to contend with in the way of flight, and discovered that anything below 170 knots and the airplane would stall out. Having to work with two hands on the stick because of the out-of-rigid conditions of the airplane, I experimented to see what I could do in the way of control to get aboard the ship. I kept my speed up and when the aircraft carrier was ready to receive me, which meant that they had a lot of airplanes in the area where I was going to land, they were there preparing to launch another fight. So they had to clear all those out of the way because this was a straight deck, not an angled deck as we have the carriers today. They had to move it all forward. When that was done and they gave me the signal “Charlie” -- meaning you clear the land – I was somewhat in the right area to start my approach which would not be a turning approach, which was the difficulty I had.

I was lined up and the carrier was in the wind, and I was talking to them about my speed and they said any speed I wanted. They had 30 knots available that the ship could make at its own speed and there was probably about that amount of natural wind in the storm. The captain said, “Bring him in any speed he wants.”

Fausone: Let me explain that for the non-aviator types here, Royce. You couldn't get your airspeed down to where it should have been for a normal landing. You were going faster than you should have, but accommodations were made because if you went too low, the plane would stall out and plunge into this frigid ocean and that would be the end of it. You and the carrier had to work together based on the condition of the plane to be able to get on board. I read somewhere that the ship had to turn a little bit to help line you up because, as you said, you had up-and-down control but not side-to-side control. They had to help out in that regard.

Williams: That’s right. I was pretty much able to maintain the altitude control, but as far as lining up I wasn't able, and I told them that. The commanding officer of the carrier was a pilot and he understood the problem. As I got in close, pointing at the ship but not lined up to make a landing, he turned the ship to line it up with me just as I needed it. I made a pretty much normal landing.

Fausone: You caught the first wire then, right? Normal landing, you hit the first wire, and all was good. Was that how it worked?

Williams: Well the first wire is nice. But, the perfect landing would be the third cross-deck pennant wire, and that's the one I did capture.

Fausone: Any stop is a good stop, let's face it.

Williams: You got it.

Fausone: Again, there was no expectation that the Navy would have to take on these Russian MiGs and so this became a publicity problem with, “We don't want to drag the Soviet Union into the Korean War.” So, the decision was made -- I guess this went all the way up to the Secretary of Defense and the President -- that this dogfight had to be kept secret. I guess they explained that to you right from the get-go.

Williams: I wasn't dealing with people at that level at that time, but they knew about it right away and had a great interest in filling in the blanks and were trying to find out from the ship what happened. The ship didn't know what happened, but the people on the Helena – on the cruiser -- had these people from the time they took off from their base until they said, “The remnant came back.” They followed it all, but they were the only ones besides the Russians that knew what was happening. On our side, because they wanted information immediately, our intelligence officer -- a poor boy -- had to make up a story and it wasn't true. I was told to report to Admiral Bristol. This was our last online combat for that period.

We were about to go into base at Yokosuka, Japan, and re-arm, and get the supplies, and for some of there was an R & R opportunity. On getting there, I was told to report as soon as possible to Admiral Bristol, who was the senior Naval officer of the Western Pacific. And I did. On arrival, I was guided to his office, and the door closed behind me and we were greeted. He then asked where the Oriskany, my carrier, got that information which was made public and was not true -- which the intelligence officer, under great pressure, made up. He knew a little bit about it. They were in our ready room which has a screen and the information passed from our combat information center, but they had very little to report. He knew a fight was engaged and he eventually gave in to pressure and went to the center on the carrier where the communications were set up with Washington and made that false report.

Fausone: Ultimately, you got debriefed, all the way up I understand. You got meetings with or were interviewed, however, you want to put it, by not only a bunch of the Admirals but the Secretary of Defense and also President Eisenhower. All along the way they're saying they don't want to pull the Soviets into this, keep this classified. And it was classified for almost 70 years.

In 1953, a year later, you received the Silver Star for this engagement although it only mentions three kills. The fourth wasn't known until Russian records were released in the 1990s. How does a young hot shot pilot, who's going to have a long career in the Navy and reach the ranks of Captain -- how do you keep this secret?

Williams: Well I was told and I obeyed. It was a bit of a problem because I knew what was being said about the whole thing was not true. Of course, it would influence my career if they knew the facts and it became well known. Whereas, it was more or less a brief moment in time, not true and more or less forgotten.

Fausone: You kept this secret, not only professionally, but personally I understand. Only after it was declassified and after some efforts to increase the recognition from a Silver Star to maybe as high as a Medal of Honor but ultimately settling on the Navy Cross, did you get it opportunity to tell this whole story to your family, including your wife.

Williams: True.

Fausone: Did they believe it or did they say, we know you're just telling another fib.

Williams: No. I just told my wife and she was more or less shocked. Her comment was, “Oh Royce.” That did it.

Fausone: It’s probably better she didn't know and worry all those years about the next mission because you flew a lot of missions after that as well.

Williams: Yes.

Fausone: You spent a long career in the Navy and serving the country and now you've had a long time to be in retirement and enjoy that. What did you learn from that experience of testing yourself in North Korea that maybe you'd pass on to other people as a little pearl of wisdom?

Williams: I probably learned what I would have had it not happened. It may sharpen the learning experience. I was a professional and dedicated. Whatever the mission, I think I always tried to do my best. We still had a lot of war ahead of us and it was different, but in support of the troops and all, it was important.

Fausone: I think today sometimes we don't hang on to some of those core, rock solid values like doing the mission, being a professional, living up to your word if you're told to keep it confidential, you keep it confidential. Those those are all good lessons for everybody to learn, even today I believe, don't you?

Williams: Yes. Of course, it deepened my faith in God.

Fausone: Absolutely. I know there was some effort to get it upgraded to the Medal of Honor, and just this year in 2023 you've received the Navy Cross. Talk to us about what receiving this second-highest award for valor in combat felt like to you and what you think it symbolizes.

Williams: Well, I had been teased with the Medal of Honor and when it didn't make it because of a turndown in the Senate, my congressman got in touch with the Secretary of the Navy who miraculously came out and visited with me for about an hour and a half. He came well prepared to have his questions answered and he went away believing there had been a miscarriage of justice and he had the authority to correct that.

In a very short time, a few weeks following that, he made up his mind that the Navy owed me a higher medal and he saw to it in a wonderful ceremony that was just amazing. It would have made quite some difference in my career, I imagine, had I been given that credit while I was on active duty. But that was not so. Whatever happened after that time had to be based on the circumstances and the performance at that time.

Fausone: Many stories of valor probably should get the nation's highest award, but don't, for any variety of reasons. I always think it's important to get recognized on these sorts of things, like for the Navy Cross, so that your larger community - whether that's where you live now, back in South Dakota, the family, other Naval aviators - so that the larger community can share in that recognition.

Based on what I saw from the ceremony, there was a lot of community support and recognition for the Navy Cross ceremony. I think that must have felt positive for you.

Williams: Well, yes indeed. I had a lot of friends out in the community at the event and quite a few that I did not know. They were all supportive and I've had follow-up conversations where it seemed to mean a lot to them -- probably not as much as to me, but it impressed a lot of people.

There were active duty personnel there and they did not know what they were facing, but who knows They may call upon it and if this means anything to them, they'll be as prepared and in the best equipment that their country has for them. So, they may get their turn.

Fausone: I've also got to say, Captain Royce Williams, you are undoubtedly at 97 years old, the best-looking Captain in uniform for that age.

Williams: You lie!

Fausone: I'm sure it was fun to be with all those folks who were looking up to you. They're not your peers, they're all younger, they're all from a different era, but looking at you thinking, “Man, there's a man's man. There's an aviator's aviator.” Again, well deserved. The story was untold for over 70 years, so we're glad Captain Royce Williams that you got a chance to receive the Navy Cross and tell a little bit of this story to our listeners here on Veterans Radio.

Williams: Well, I'm pleased to do so.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED