Charles A. Lindbergh

The Lone Eagle

One might have called it a "routine milk-run", that chilly night of September 16, except for the fact that any flight in 1926 was far from routine and the cargo wasn't milk but mail. As a chief pilot for the Robertson Aircraft Corporation, the pilot they all called Slim had traveled this route many evenings. It was in fact, a routine--

One might have called it a "routine milk-run", that chilly night of September 16, except for the fact that any flight in 1926 was far from routine and the cargo wasn't milk but mail. As a chief pilot for the Robertson Aircraft Corporation, the pilot they all called Slim had traveled this route many evenings. It was in fact, a routine--

- Depart Lambert field in St. Louis with bags of mail at 4:25 p.m.

- Stop at Springfield, Illinois, shortly after 5 p.m. to exchange bags of mail.

- Arrive at Peoria, Illinois, an hour later, then depart for Chicago.

- Arrive at Chicago so the mail could be routed east and west.

- Return to St. Louis to make a similar run once again.

With the onset of Autumn, darkness usually sets in during the last leg of the trip. On this evening the shadows that crept across the fields below were deepened by a heavy fog blowing in off the Great Lakes. The mist rose from the ground to an elevation of 600 to 900 feet, making it impossible to fly beneath it in search of the airfield at Maywood that served as Chicago's airmail port.

Slim took a compass reading and continued towards the general area of the airstrip. At 7:15 p.m. the top layers of fog reflected a glow indicating a city below, but there were no openings to allow the pilot to see the ground in an effort to locate the landing field. Several times he descended as low as 800 feet where the fog bank ended beneath an otherwise clear sky above. On the ground, anxious crews directed searchlights heavenward and burned two barrels of gasoline, but the saving signals could not penetrate the mist.

Slim circled for 35 minutes, then headed west to avoid Lake Michigan. Fuel was low and if he was forced down, he wanted solid earth beneath him. At 8:20 the engine of the powerful Liberty engine of his DH-4 stopped and the pilot turned on his reserve. It would allow him 20 minutes to find a hole in the fog and land safely.

Circling at 1,500 feet the fog refused to part for the faltering airmail plane. Slim stuck a flashlight in his belt, determined to jump when the reserved engine had expended the last of its fuel. He struggled unsuccessfully to open the compartment containing bags of mail to toss it earthward before his airplane crashed, then gave up on the effort. At the last moment, he noticed a brief flicker of light, the first he had seen in two hours. Dropping to 1,200 feet he released a flare, his heart sinking as it illuminated only the top of the heavy fog bank and then disappeared into the darkness below. With only seven minutes of fuel remaining, there were no other options.

The pilot climbed to 5,000 before that engine sputtered and died completely. Slim stood up in the cockpit, stepped over the cowling on the right-hand side, and jumped. Seconds later, he pulled the ripcord and felt the reassuring tug of his parachute. Pulling the flashlight from his belt, he flashed it down and across the top of the fog bank below when he heard an unexpected sound -- the roar of his airplane's engine returning to life as it began a spiral around his slowly falling chute. On its first loop, it came within 300 yards, and now Slim feared he might be knocked from the sky by his own airplane. Before jumping he should have cut the fuel switches--but didn't. Now, he guessed, as the plane nosed downward a small amount of fuel in the back of the tank had rushed forward to reinvigorate the engine.

As the fog enveloped his falling body he could still hear his airplane circling, falling at about the same rate as his own body. With each circle, however, the aircraft seemed to be moving further away in ever-widening loops. After five loops, the threat had passed and Slim prepared himself for the next danger--collision with the ground. He crossed his legs to avoid straddling a fence or other protrusion, used his hands and arms to protect his face...and waited.

He saw the ground moments before landing in a cornfield. Picking himself up he could discern no major injury, so he packed up his chute and headed out in search of a farmhouse. He found one and enlisted the aid of the farmers in locating his plane, which had crashed two miles away. Before daybreak the mail was en route by ground to the Ottawa Post Office for delivery to Chicago and Slim was returning to St. Louis to find another airplane. After all, the mail had to get through, and Slim was the main pilot on this route. Such incidents were to be expected in the early days of aviation.

Flying mail in the 1920s was a dangerous job, usually flown in aging DH-4 Flaming Coffins left over from the war and committed to the air in all kinds of inhospitable weather. Slim had been fortunate to safely jump from his own to touch earth without injury. Normally that act would have qualified him for membership in an elite fraternity...The Caterpillar Club... composed of pilots who had made an emergency jump from a doomed airplane. Slim didn't need the fateful night of September 16 to grant him membership, however. He was already a member...twice. In fact, within six weeks he would have to make yet a fourth emergency jump, making him the all-time record holder in that fraternity. That record exists even today. The caterpillar club was so named because parachutes were made of silk, spun by the silkworm caterpillar.

Any number of things could have gone wrong on that, or any other nights in the air between St. Louis and Chicago. Had the worst happened, the tragedy would have passed with little notice. The death rate among early mail pilots became so high as to eventually lead to charges of government ineptitude, and tragedy struck with such frequency that brave young pilots died in oblivion. The local paper might report the death, maybe even print the name of the pilot. Those who read the story might question what motivated these young men who laughed at danger to fly mail, and wonder what futures were lost in their untimely death.

Had the worst happened on the St. Louis-Chicago route, who would have missed the lanky young pilot they called Slim?

Because the worst didn't happen, that question can be answered -- Slim's true name would soon be written in history, for he was: Charles Augustus Lindbergh.

Slim Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan on February 4, 1902, the son of Evangeline and Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr. His father was a successful attorney who lived and practiced law in Little Falls, Minnesota. He was elected to the U.S. Congress when Charles was 4-years old and served therein for a decade until 1917.

Slim Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan on February 4, 1902, the son of Evangeline and Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr. His father was a successful attorney who lived and practiced law in Little Falls, Minnesota. He was elected to the U.S. Congress when Charles was 4-years old and served therein for a decade until 1917.

For the next several years young Charles traveled with his family as they commuted from the Minnesota home to Washington, DC, as well as elsewhere. He later wrote, "Up to the time I entered the University of Wisconsin (1920) I had never attended for one full school year, and I had received instruction from over a dozen institutions, both public and private, from Washington to California.

"Through these years I crossed and re-crossed the United States, made one trip to Panama, and had thoroughly developed a desire for travel, which has never been overcome."

Lindbergh's interest in travel took a new twist at the age of ten when he attended his first air show. It inspired an interest in air travel that was never overcome. In 1918 he graduated from Little Falls High School in his home state and enrolled as an engineering student in the University of Wisconsin in 1920. During his freshman year, he found recreation in shooting matches on the R.O.T.C. team, but aviation became more and more the focus of his dreams for the future.

Lindbergh's interest in engineering came naturally. His maternal grandfather was a dentist with an inquisitive mind and experimental nature, who pioneered the use of porcelain in dentistry and became known as the father of porcelain dental art. Years later young Charles would himself contribute materially to the field of health, collaborating with Dr. Alexis Carrel in the development of the perfusion pump that would ultimately result in the creation of an artificial heart.

In February 1922 Lindbergh left college to pursue his three passions in life:

- Travel

- Aviation

- Engineering

These were a trichotomy that would one day make him the most famous aviator of all time. But on April 9, 1922, when Charles Lindbergh made his first flight as a passenger in the plane-for-hire of Otto Timm in the sky over Lincoln, Nebraska, he was just another unknown, young, would-be airman. In the weeks that followed he began his own flight training, compiling eight hours of instruction at the cost of $500 by the end of May. Before Lindbergh could make his first solo flight, however, the instruction plane was sold.

Throughout that summer the young man spent a lot of time in the air, but little of it in the cockpit. Throughout Wyoming and Montana, Lindy dazzled crowds as a wing-walker, parachutist, and performer the other aerial feats that highlighted the barnstorming era.

In the spring of 1923 the elder Lindbergh, despite his general aversion to the airplane, fronted enough money for his 21-year-old son to purchase his first airplane. It was a war-surplus Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, auctioned to young Charles for a price of $500, a fraction of what it had cost the U.S. Government during the war. On April 9 Charles Lindbergh gassed up his first airplane, taxied to the end of the airstrip at Americus, Georgia, where the plane had been sold, and lifted off to make his first solo flight. From there it was on to Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and across the South. For $5 Lindbergh would provide the daring and the inquisitive with a five to ten-minute flight. Recalling those early days he wrote in his 1927 account of the flight that made him famous: "Some weeks I barely made expenses, and on others, I carried passengers all week long at five dollars each. On the whole, I was able to make a fair profit in addition to meeting expenses and depreciation."

Though Lindbergh's ultimate destination upon taking possession of his first airplane was to fly in Texas, his route became a circuitous one that led home for a brief period. There he convinced his father to fly with him over Redwood Falls, winning over the first of many converts. Mother Evangeline also joined her son in the air and flew with him at every opportunity.

Before resuming his itinerary south in September, Lindbergh submitted forms to Washington, DC, requesting duty with the United States Army Air Service. The following January he reported to Chanute Field in Illinois to take his entrance examinations. A short time later he received orders to report to Brooks Field in San Antonio, Texas, to join a class of flying cadets scheduled to begin training on March 15. Excitement ran high among the 104 cadets, all of whom were eager to fly the Army's newer and fastest airplanes. None were daunted by reports of a wash-out rate of 40% in the first phase of training.

Classes were tough and demanding, both mentally and physically. Just weeks after the training began, Lindbergh's already stressful situation was compounded by the death of his father. Lindbergh hung in there, survived the dreaded "Benzine Boards" that sent more than half his classmates home prematurely, and was among the remnant of the original class that was sent to Kelly Field near San Antonio in September.

It was during this final phase of training that Lindbergh became a member of the caterpillar club, making his first emergency jump on March 5, 1925, after a mid-air collision with another airplane during war games. Weeks later the young man was one of eighteen cadets from the original class of 104 to receive his wings and commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Service Reserve Corps. Simply surviving to graduation was a considerable accomplishment alone. Second Lieutenant Charles A. Lindbergh graduated at the head of the class.

Lindbergh returned to the flying circus circuit during the summer of 1925 and made his second emergency jump during a test flight at Lambert Field on June 2. In July he spent two weeks instructing other pilots at Richards Field in Missouri as part of his reservist military commitment, then flew passengers for the Missouri National Guard encampment in August. In November he was promoted to First Lieutenant in the 110th Observation Squadron, 35th Division, Missouri National Guard. He also learned that his friends in the Robertson Aircraft Corporation had succeeded in their bid for the government mail contract on St. Louis/Chicago route. He began flying that route the following spring.

Unlike air show aviation, performed before crowds of spectators on the ground, flying the mail was a dark and lonely job. The pilot usually flew alone, often at night, and in all manner of weather. It was a solitary lifestyle, isolated high above all signs of life...a man and his airplane. It was a great experience, testing one's abilities against every imaginable condition both mechanical and natural. It also granted the pilot hours of solitude. Somewhere along in the dark skies between St. Louis and Chicago during the Autumn of 1926, a lone airmail pilot everyone called Slim began filling those lonely hours with an incredible dream. As winter set in, that dream began to take shape. It would come to life in:

The Great 1927

New York-to-Paris Air Derby

The summer and fall of 1925 were both perilous and dramatic times in the history of aviation, just 22 years after the first heavier-than-air flight at Kitty Hawk. This was the year the Navy suffered the disastrous loss of the Shenandoah airship and the ill-fated flight from California to Hawaii. It was the year Billy Mitchell was court-martialed in Washington, DC. It was the year that Dwight Morrow convened the board that would ultimately lead to the designation of the Army's air arm as the U.S. Air Service, and the same year that a young barnstormer named Jimmy Doolittle won the Schneider Cup Race at Baltimore, MD, setting a record speed of 245.7 mph for a seaplane.

The following year became even more dramatic. In 1926 the big nine-cylinder radial air-cooled Wasp engine was introduced. Lieutenant J. A. Macready set an American altitude record of 38,704 feet; Robert H. Goddard launched the world's first liquid-fueled rocket at Auburn, Massachusetts; and the U.S. Army Air Corps was born. Navy Commander Richard Byrd led the first flight over the North Pole, and President Coolidge signed the Air Commerce Act to regulate civil aeronautics. It was also the year that a foreign aerial legend brought his own brand of excitement to the United States...and the world.

Captain René Fonck was a French war hero; a highly decorated and dashing young pilot whose name was spoken with reverence around the world. During the war, he had shot down an incredible total of 125 German aircraft and was credited with 75 official victories, second only to Germany's Red Baron. In 1926 the man who had already demonstrated that he was the master of the skies announced that he would do what no man had done before...

Fly from New York to Paris, and collect the coveted Orteig prize.

Early aviation was a spectator sport, daring airmen charging admission to curious spectators to demonstrate what could be accomplished by the airplane. As the number of pilots increased, so too did the competition, and aviation became more of a contest than a show. In 1910 the New York World offered a $10,000 prize to the first pilot to fly from Albany to New York City. Glenn Curtiss who would become among the best known of airplane manufacturers claimed the prize after piloting his pusher plane at an average of 52-miles per hour across the 152-mile trip with two stops for fueling.

The amazing feat was followed by rival publisher William Randolph Hearst's 1911 offer of a $50,000 prize to the first aviator to fly coast-to-coast across the United States in thirty days or less. Cal Rodgers was the first to make the transcontinental trek but was disqualified. The trip took him a total of 84 days. Only eleven years later a young pilot named Jimmy Doolittle made the same trip in fewer than 24 hours...the first man in history to do so.

Pilots the world over were pushing the envelope in the post-war years, and the early 1920s were filled with new records for both speed and distance. In 1924 General Billy Mitchell was the man behind an around-the-world flight. Six U.S. Air Service pilots in three planes completed the world circuit in 175 days after departing Seattle, Washington, on April 6, 1924.

Actually, four Air Service planes began the historic 1924 world tour, each named for an American city: Seattle, Chicago, New Orleans, and Boston. The Pacific Ocean was negotiated from Alaska, which presented its own series of challenges. But the greatest hurdle in the 26,000-mile odyssey lay towards the end...crossing the Atlantic. It was accomplished in an island-hopping series of flights from the Orkney Islands north of Scotland to Iceland, then to Greenland, Labrador, and home to North America. The challenge resulted in the loss of Boston, though the entire trip was accomplished without loss of life.

So formidable a barrier was the Atlantic Ocean, that in 1919 a French hotel operator named Raymond Orteig offered a prize of $25,000 to the first pilot to fly nonstop between New York and Paris. Orteig lived in New York but could see the world shrinking in size with the advent of aviation, and was eager to see the first successful nonstop crossing of the Atlantic. By the time of the Air Service's flight in 1924 the Atlantic had been successfully traversed three times, all in 1919, but the Orteig prize for a New York/Paris trip remained unclaimed.

The first successful crossing began on May 8, 1919, when three Navy "flying boats" took off from Newfoundland. Numbered NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4, each carried a 6-man crew for the hop from Newfoundland to the Azores. The NC-1 went down at sea. Fortunately, the crew was rescued by an American destroyer. When the NC-3 failed to arrive in the Azores, a sense of doom pervaded the U.S. Navy. Unbelievably, after days with no sign of the airplane, it drifted into the harbor at Porta Delgada backward...still afloat and the crew alive after a harrowing journey. Only the NC-4 successfully made the aerial crossing.

The first successful crossing began on May 8, 1919, when three Navy "flying boats" took off from Newfoundland. Numbered NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4, each carried a 6-man crew for the hop from Newfoundland to the Azores. The NC-1 went down at sea. Fortunately, the crew was rescued by an American destroyer. When the NC-3 failed to arrive in the Azores, a sense of doom pervaded the U.S. Navy. Unbelievably, after days with no sign of the airplane, it drifted into the harbor at Porta Delgada backward...still afloat and the crew alive after a harrowing journey. Only the NC-4 successfully made the aerial crossing.

Two weeks later British war veteran pilots John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown made the 1,890 flight across the North Atlantic from Newfoundland to Ireland. In July the British dirigible crossed east to west from Britain to New York. It was the last crossing until the Air Service flight of 1924, none of them fulfilling the requirements of the Orteig Prize. There was a large difference between the 1,890-mile crossing from New Foundland to Ireland and the 3,610-mile distance from New York to Paris. By 1926 it had been seven years since Raymond Orteig had issued his challenge and, with the advances in airplane design, the time was ripe for some brave soul to claim it.

In 1926 Captain Fonck's arrival in New York by boat touched off a current of excitement that rippled around the world. The French were justly proud to see one of their own legends become the first to make the historic Atlantic crossing. Americans too fell in love with the dashing war hero whose fame and feats had made him a world hero, even among the Germans he had fought during the war. The flight became even more personal for Americans when Captain Fonck announced that his navigator for the flight would be an American, Lieutenant Lawrence Curtain. The huge Sikorsky S-35 with its three large engines were equally impressive.

This was a moment in search of new heroes, and the world watched with great anticipation.

Early on the morning of September 21, 1926, Captain Fonck drove to Roosevelt Field on Long Island. He had chosen to make the trek from west to east to take advantage of prevailing eastbound winds and selected this particular Tuesday morning so he could fly beneath a full moon when darkness fell. His gigantic airplane would carry a 3-man crew in addition to Fonck, and 2,500 gallons of gasoline were being poured in the tanks when the war hero arrived at the field. Dressed in his crisp blue French Army uniform, replete with an array of medals, he looked very much the hero beneath the headlights of the hundreds of automobiles that lined the airstrip to illuminate the pre-dawn darkness.

At 6:00 a.m. the fueling was complete and Fonck turned over the engines. With his crew aboard, the S-35 weighed fourteen tons. It would require every yard of the one-mile runway and every rpm he could muster from the three big engines, to achieve the 80 mile-per-hour speed necessary to get the huge airplane off the ground.

Take-off was almost a circus with motorists driving parallel to the S-35 as it lumbered down the runway, slowly picking up speed. Even in the dim light of the early morning, it didn't take long for the crowd to notice the trail of dust that followed the airplane as it struggled to gain speed. As the heavy plane had bumped and bounced across the airstrip, the landing gear on one side of the plane had been damaged and began dragging across the field. The drag wouldn't allow Fonck to coax more than 65 m.p.h. out of his engines.

To cut the engines at that point would deprive the pilot of any control over his speeding airplane and would probably cause it to nose over. To veer away from the landing strip would undoubtedly send the airplane careening into the crowds along the sidelines. Despite the futility of the effort, Fonck had no choice but to continue straight ahead in hopes he could somehow get his plane airborne.

It was a valiant, sacrificial effort against long odds. This time the pilot who had defied the odds again and again in the war-time skies over France, lost the gamble. The crowds watched in shocked horror as the S-35 reached the end of the runway and tumbled out of sight into a gully. Seconds later the morning skies were lit up by the brilliant eruption of 2,500 gallons of gasoline. As the sea-breezes whipped the heavy black smoke around, the stunned spectators saw Captain Fonck climbing out of the gully, followed by Lieutenant Curtain. No one else appeared. The other two French crew members died in the flames.

But for the freak incident that damaged Captain Fonck's airplane on take-off, few people doubted that he would have been the first to claim the Orteig Prize. The tragedy might have deterred future attempts, but the men who pioneered aviation in its infancy were a special breed: daring, adventurous, and willing to accept the risks. The advent of winter would prevent any further attempts in 1926, but during those last months of the year, word began to circulate that several teams were gearing up for an attempt the following spring. Amid the hype and anticipation, it became known as "The Great 1927 New York-to-Paris Air Derby".

When Raymond Orteig established his prize, it became the responsibility of the National Aeronautic Association to establish the guidelines and rules for any attempt to claim it. As 1926 faded and the new year began, applications began coming in from an impressive array of contestants, all of them determined to make 1927 the year of conquest.

Among the first to announce his intent was another war hero, Captain Charles Nungesser who had shot down 43 enemy planes during the war to become France's third-leading ace. Nungesser announced that he and his navigator, Captain Francis Coli, would attempt the flight from east to west in the early spring.

Two U.S. Naval officers, Lieutenant Commander Noel Davis and Lieutenant Stanton Wooster also submitted applications. Charles A. Levine, a civilian and the well-known and somewhat eccentric president of the Columbia Aircraft Corporation, announced he too would field a team, playing his own effort for all the publicity and hype he could muster.

On February 25, Naval aviator Commander Richard Byrd, Jr. visited the White House to receive the Medal of Honor from President Calvin Coolidge. The previous year Byrd had become a national hero for his flight over the North Pole. Now the newly-decorated American aviation hero announced he would also enter the New York-to-Paris air derby, not for the prize but for the value of scientific research.

The mix of these four teams, all composed of men well known and revered for their courage and accomplishment, provided great material for the early 1927 newspaper hype for the coming spring. Almost lost among these four applications was a fifth. It had arrived with no mention of a team or even an accompanying navigator. It was signed simply "C.A. Lindbergh".

The media covered the preparations of the four leading contenders steadily in the early months of 1927. The biggest question for all seemed not to be who would make the crossing first, but which of the four would be first to make an attempt. Commander Byrd seemed to be the American favorite with his large Fokker tri-plane named America. In the early spring, Byrd took America up for a test run over New Jersey. All went well until the Commander brought it in for a landing. The nose-heavy airplane tipped over, breaking Commander Byrd's arm in the resulting crash, and postponing the American hero's plans several weeks.

The odds now seemed to favor the wealthy Levine, whose single-engine airplane named Columbia was christened on April 24. Following the splash of ginger ale against its side, pilot Clarence Chamberlain taxied down the runway for the maiden flight. During take-off one wheel fell off the plane, forcing Chamberlain to use all his skills to land again on one wheel. In the process a wing scraped the ground, putting the Columbia back in the hangar for repairs.

Lieutenant Commander Davis and Lieutenant Wooster were even less fortunate two days later when they took their airplane named American Legion for a test flight over Virginia. Both men were killed when their heavily-loaded airplane stalled and crashed into a swamp during take-off.

In Paris, French war-ace Captain Charles Nungesser proclaimed, "I am attempting the flight to bring honor to French aviation." All of France cheered as he and Captain Coli took off from Le Bourget airfield on the morning of Sunday, May 8. Their boat-plane was last seen over Ireland as it turned into the formidable North Atlantic. So intense was the anticipation of their success, even in the west, that all eyes were on the heavens Monday morning and watchers reported seeing the plane over the North American continent. The Monday morning newspapers in Paris eagerly announced in a special headline edition that the two aviators had arrived to land on the water at the foot of the Statue of Liberty amid a fleet of flag-flying welcome ships. It was wishful thinking. The White Bird had disappeared into the vast Atlantic after last being seen over Ireland, and no trace of its fate would ever be found.

As the French newspapers printed their retraction, an equally false rumor was written. The two French aviators, it was reported, had been lost in a storm over the Atlantic because the Americans had withheld weather information from the pilot and his navigator. A deeply despondent French public was quick to believe the rumor, and such anti-American sentiment swept through Paris that the American ambassador cabled Washington to advise that it would be unwise for any American pilot to attempt to fly to Paris until the mood settled.

In fact, the American public was as heartbroken at the French tragedy as were the people of that nation. The air derby had become less of a challenge between competing nations, and more of a contest between man and the raging Atlantic. In little more than two weeks, the four leading contenders in the New York-to-Paris contest had all met with tragedy. Nothing had been heard from the fifth applicant, an unknown airmail pilot from St. Louis named C. A. Lindbergh.

Little had been heard of the fifth applicant in the New York-to-Paris Air Derby because the young man known only as C.A. Lindbergh was busy preparing to make history. He later wrote,

"I first considered the possibility of the New York-Paris flight while flying the mail one night in the fall of 1926. Several facts soon became outstanding. The foremost was that with the modern radial air-cooled motor, high life airfoils, and lightened construction, it would not only be possible to reach Paris but, under normal conditions, to land with a large reserve of fuel and have a high factor of safety throughout the entire trip as well."

In December 1926, Slim Lindbergh went to New York to obtain the necessary details for his own entry into the air derby, then began designing the airplane he believed could help him accomplish what no other man had done before.

While Commander Byrd had accomplished his North Pole flight in his famous Fokker tri-plane, Lindbergh reasoned that a monoplane would be more efficient for the long, non-stop flight to Paris. A single wing had less resistance against the winds, making it far more fuel-efficient. As opposed to men like Captain Fonck who had planned his flight aboard an airplane equipped with three large engines, Lindbergh also opted for a single, 200-horse-power radial air-cooled engine. Multiple engines provided somewhat of a safety factor, for if one engine failed, others remained to try and get the airplane to safety. In a single-engine airplane, mechanical failure would result in the plane going down over the Atlantic--and almost certain death. Lindbergh felt confident in the newer engines to be sufficiently advanced beyond the likelihood of failure.

Lindbergh estimated that the airplane he had in mind would cost about $10,000, five times the $2,000 he had personally saved. He turned to air-minded businessmen in St. Louis, convinced them to finance the project, then made two more trips to New York early in 1927 to finalize the details. On February 28 he placed an order with Ryan Airlines of San Diego to build his airplane, then went to California to both plans and supervise.

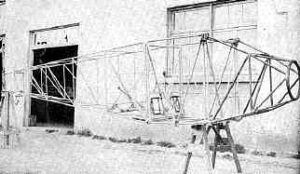

The Ryan aircraft manufacturing plant was little more than a crew of dedicated mechanics operating out of an old fish cannery along the San Diego waterfront. When the contract was signed on February 28, Lindbergh was promised his unusual airplane would be completed in two months. If all went according to plan, the stage would be set for an early spring trans-Atlantic flight. For his own part, Lindbergh spent those two months nearly living in the building where his plane was being constructed.

The Ryan aircraft manufacturing plant was little more than a crew of dedicated mechanics operating out of an old fish cannery along the San Diego waterfront. When the contract was signed on February 28, Lindbergh was promised his unusual airplane would be completed in two months. If all went according to plan, the stage would be set for an early spring trans-Atlantic flight. For his own part, Lindbergh spent those two months nearly living in the building where his plane was being constructed.

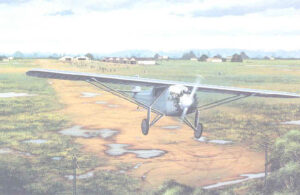

Slowly that special plane began to take shape--Spartan in appearance but practical in its application. The big Wright engine was housed in a cowling covered by aluminum. The remainder of the airplane was sheathed in tightly drawn fabric over a well-constructed frame. Gasoline tanks were housed in the wings and supplemented by an additional tank behind the engine in the fuselage, balanced carefully over the fixed landing gear. This large tank made it possible to store the extra fuel needed for the 3,610-mile odyssey, but the need to balance that extra weight blocked the pilot's forward view. Seated in his light, wicker seat behind the tank, Lindbergh would be required to navigate solely by looking left or right through the side windows, or by using a crude periscope constructed of tubing and two mirrors, to see what lay ahead. In honor of the businessmen in Iowa who put up the money to build the gray monoplane, Lindbergh named it:

Spirit of St. Louis

Engine: 9 Cylinder, 220-HP, Air-cooled Wright J-5C Whirlwind

Wingspan: 27'

Length: 27'8'

Height: 9'8"

Weight (empty): 2,150 lbs.

Tail Number: N-X-211

An expert mechanic, Lindbergh was involved in every step in the construction of his airplane, working closely with Chief Engineer Donald Hall. The dedicated staff worked long and hard to create in the old warehouse, the airplane drafted on paper by Hall. Lindbergh walked the floors of the plant regularly, to see his dream take shape. He also spent long hours planning his trip...one he would make alone. All other competitors in the Great Air Derby planned to make the historic Atlantic crossing a team effort--at the very least consisting of a pilot and navigator. Lindbergh planned to fly alone, replacing the weight of a navigator with fuel. This meant he would serve as both pilot and navigator.

An expert mechanic, Lindbergh was involved in every step in the construction of his airplane, working closely with Chief Engineer Donald Hall. The dedicated staff worked long and hard to create in the old warehouse, the airplane drafted on paper by Hall. Lindbergh walked the floors of the plant regularly, to see his dream take shape. He also spent long hours planning his trip...one he would make alone. All other competitors in the Great Air Derby planned to make the historic Atlantic crossing a team effort--at the very least consisting of a pilot and navigator. Lindbergh planned to fly alone, replacing the weight of a navigator with fuel. This meant he would serve as both pilot and navigator.

While the Spirit of St. Louis took shape in the warehouse, Lindbergh worked out his navigational plan. He would take off from New York to make the circle route to Paris: northeast over Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, then across the North Atlantic to traverse Ireland at its southern tip, across England and the channel that separated it from the European continent, and finally...if all went well...PARIS!

On a flat piece of paper, it appears that Lindbergh's route was a circuitous one, going out of his way to avoid an endless expanse of ocean in a straight-line flight. In point of fact, because the planet is a globe and not a flat piece of paper, his flight plan took advantage of the Earth's curvature to give him the shortest route to Paris, a distance of 3,610 statute miles.

On a flat piece of paper, it appears that Lindbergh's route was a circuitous one, going out of his way to avoid an endless expanse of ocean in a straight-line flight. In point of fact, because the planet is a globe and not a flat piece of paper, his flight plan took advantage of the Earth's curvature to give him the shortest route to Paris, a distance of 3,610 statute miles.

Lindbergh would navigate by dead reckoning, looking for landmarks to Boston, then Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, before the 1850 mile expanse of the North Atlantic. Flying at close to 100 mph, he would take compass readings and alter his course each hour. He estimated that this crude system would suffice. Even if he reached Europe 300 miles off course, he would have enough fuel remaining to reach Paris.

Lindbergh also carefully determined the necessary supplies he would take on his flight, ever mindful of the fact that each additional item in his inventory would demand extra fuel. The final shopping list provided him sustenance for one full day, as well as emergency supplies in case something went wrong. These would be stowed behind his wicker seat in the cramped cockpit, along with a raft in case he went down over the Atlantic.

2 Flashlights

1 Ball of String

1 Ball of cord

1 Hunting Knife

4 Red Flares

1 Box of Matches

1 Large Needle

1 Canteen - 4 quarts

1 Canteen - 1 quart

1 Armbrust Cup

1 Air Raft with pump

5 Cans Army rations

2 Air Cushions

1 Hack saw blade

Though the undertaking the young pilot was endeavoring to achieve was fraught with danger, Lindbergh was never foolish. Every aspect of his airplane, every item it would carry, and every detail of the route and its navigation was carefully thought out and planned for.

"Day and night, seven days a week, the structure grew from a few lengths of steel tubing to one of the most efficient planes that has ever taken the air," Lindbergh later wrote. "During this time it was not unusual for the men (of Ryan Aircraft Manufacturing) to work twenty-four hours without rest, and on one occasion Donald Hall, the Chief Engineer, was over his drafting table for thirty-six hours."

On April 28 the Spirit of St. Louis was completed and Lindbergh took it up for its test flight in San Diego. Few outsides of the close-knit family of dedicated workers at Ryan even took notice. All of America's attention was focused on the East Coast where in previous days all three top American contenders for the Orteig Prize had suffered setbacks, the two men flying the American Legion losing their lives. The applicant known only at "C.A. Lindbergh" had been all but forgotten.

Throughout the following week, Lindbergh continued to test-fly Spirit of St. Louis, and word began to get out about the unknown male pilot who was the fifth contestant for the Orteig Prize. As details of the plan emerged...that Lindbergh would fly a single-engine monoplane alone across the Atlantic, media reports began to refer to him as a "flying fool". In the face of the failure of Fonck the previous year, and the setbacks suffered by the rich and famous in the race this year, it was hard to give Lindbergh serious consideration.

For Lindbergh, the final test flight of the Spirit of St. Louis would be the trip from San Diego to New York. The distance was nearly equal to that of the New York-to-Paris flight. Now more than pleased with the performance of his airplane, Lindbergh was eager to get going when a storm moved in from the Pacific to hand him his first setback. For three days he anxiously monitored the weather report and was discouraged to still be stuck in San Diego on May 8 when Captains Nungesser and Coli took off from Paris. He found no joy in the report the following day that both men had failed, and were presumed lost, despite the good news from the San Diego Weather Bureau that the now 4-day storm was clearing.

At 3:55 p.m. the following day, May 10, the Spirit of St. Louis took off from Rockwell Field. Fourteen hours and twenty-five minutes later Lindbergh was welcomed at Lambert Field in St. Louis by Harry Knight and Harold Bixby, two of the key financiers of the venture. In anticipation of the main event, the fact that Charles Lindbergh had just completed the longest nonstop solo flight in history went almost completely unnoticed.

"How long are you staying, Slim?" they asked. "We have several dinner invitations for you."

"I'll stay as long as you want me to," Lindbergh replied. "But I think I ought to go right on to New York. If I don't, somebody else will beat us to the take-off." Indeed, Charles Levine had already announced that his Columbia was repaired and nearly ready for its attempt, and Richard Byrd's America was undergoing final preparations at Curtiss Field.

At 8:13 the following morning, Lindbergh departed Lambert Field to arrive at Curtiss Field at 5:33 p.m. New York Daylight Saving Time (5:33 CST).

In that final leg, he had set another record, the fastest transcontinental flight in United States' history.

From the moment of his arrival in New York on May 12, 1927, until his successful arrival in Paris nine days later, Charles Lindbergh became a phenomenon unlike any previously witnessed in history. While his historic flight revolutionized the way we view our world, courageous and historic flights were common in the early decades of aviation. Perhaps what set Charles Lindbergh apart from other heroes of the day was not so much what he did, but who he was.

From the moment of his arrival in New York on May 12, 1927, until his successful arrival in Paris nine days later, Charles Lindbergh became a phenomenon unlike any previously witnessed in history. While his historic flight revolutionized the way we view our world, courageous and historic flights were common in the early decades of aviation. Perhaps what set Charles Lindbergh apart from other heroes of the day was not so much what he did, but who he was.

Lindbergh came to New York virtually unknown, the long shot in the great Air Derby. During the Roaring 20s with its excesses, over-indulgence, and social positioning, the young man was almost a breath of fresh air. He didn't smoke, didn't curse, and possessed a strong but gentle personality. He was self-confident, but certainly not cocky. In fact, if anything he seemed genuinely shy and humble. The New York Times reported:

"No one ever more perfectly personified youthful adventure than this young knight of the air....There were many girls in the crowd who watched the good-looking pilot with undisguised admiration. Lindbergh seems to be girl-shy, but they 'simply adore' him."

Following Lindberg's arrival at Curtiss Field, media attention reached new highs. Both the Columbia and America were also at the field and Levine and Byrd had both announced the two airplanes were nearly ready to go. The crews of both competitors were cordial to each other as well as to the newly arrived airmail pilot, but the sense of competition was running at new levels. Poor weather prevailed for days, but there was a general consensus that upon the first break in the skies over the Atlantic, one if not all three airplanes, would be taking to the air.

For the first time now, Charles Lindbergh began getting heightened coverage in the daily newspapers. The long-shot has always intrigued Americans, who enjoy pulling for the underdog. Lindbergh's unique approach...one engine, one wing, one man...also became the focus of great discussion. While serious doubt existed that a lone pilot could endure the rigors of a 36-hour flight, the idea was inspiring. Somewhere the media coined a new nickname for Slim Lindbergh, referring to him as The Lone Eagle. It, like the subsequent Lucky Lindy, was a moniker the young man never liked and one which his friends avoided ever using.

For his own part, Lindbergh spoke as if his flight would be a team effort anyway. His references to the Spirit of St. Louis placed the airplane on par with himself. He spoke of a collective "We", and such would be the title of his published biographical account of these events a year later.

Thursday, May 19, 1927

The rain was falling in New York and fog shrouded the coast all the way to Newfoundland. The nearly week-old storm over the North Atlantic continued to preclude any hopes of the anxious aviators to take off for Paris. Charles Lindbergh used the continuing delay to drive to Patterson, NJ, to visit the Wright plant in the morning, then returned to New York where he hoped to watch a performance of Rio Rita. By six o'clock that evening he was en route to the theater with friends, stopping only to check the weather forecast. He was surprised to learn that the front was breaking up, and conditions were clearing over the Atlantic. Returning to his friends he announced, "Let's get back to the airfield. I'm going to take off tomorrow morning."

At the airfield, he arranged for final preparations, the servicing and final checks of his airplane, and a partial fueling of the tanks. Shortly after midnight, with his airplane entrusted to the care of dedicated ground crews, Lindbergh returned to his hotel to try to get some sleep. His mind continued to plot every eventuality, and sleep eluded him. Shortly before 3:00 a.m., he was back at the airfield making final preparations.

Friday, May 20, 1927

The Spirit of St. Louis could not take off from Curtiss Field, so in the early morning hours, it had to be transported to Roosevelt Field. To accomplish this the tail was hoisted onto the bed of the truck, then the silvery airplane was slowly towed backward across the muddy roads to the field at Long Island. Five motorcycle policemen escorted the airplane, arriving shortly before dawn.

Lindbergh quickly noticed America parked near the muddy airstrip, a few of its crew milling around, but apparently only preparing it for another test flight. Either Richard Byrd had not heard the weather report, or he had for some other reason determined that today was not the right day to make his own attempt. Even at that early morning hour, more than 500 spectators had gathered at the field, but on this morning they would witness the take-off of only one of the three remaining entrants in the Air Derby.

The Spirit of St. Louis had been partially fueled at Curtiss Field so as not to add too much weight during the trip to Roosevelt Field. Now a bucket-brigade passed 451 additional gallons of gasoline in 5-gallon containers to finish the job. The rain was easing to a slow drizzle, but the dirt runway had turned to mud. Lindbergh, in an effort to reduce resistance during takeoff, greased the wheels of his airplane. He ate one of six sandwiches he had been given, stowed the other five in the cramped cockpit, and noted the presence of a slight tail-wind.

At about 7:40 a.m. the big Wright engine was started and Lindbergh listened to its steady throb. Everything, except for take-off conditions, seemed right. If he could get his heavy airplane off the muddy runway, Lindbergh was certain this would be the moment he had dreamed of months earlier while flying mail from St. Louis to Chicago. Richard Byrd and Clarence Chamberlain both showed up at the airstrip, each shaking hands with the young airmail pilot and wishing him well. At 7:51 Lindbergh strapped himself in the cockpit, closed the door, and leaned out the window to exclaim: "What do you say...let's try it."

7:52 a.m. - Hundreds of spectators and news reporters watched in anticipation as the large silvery airplane pushed its way down the muddy airstrip, remembering well what had happened to Captain Fonck only six months earlier. The Spirit of St. Louis picked up speed...lifted off the ground for a moment, then settled back into the mud as Lindbergh remained at the controls. Continuing to pick up speed, power lines loomed ahead as the pilot struggled to coax more speed out of the engine.

Now airborne, Lindbergh turned his airplane to the right to clear a small hill, then continued to climb. A Curtiss Oriole flew alongside him as he headed out over Long Island Sound, a photographer capturing the first few miles for history. Then it turned back, leaving Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis alone in the heavens.

The weather had indeed cleared, leaving a beautiful morning sky. Lindbergh flew low, often only ten feet from the crest of the waves and passing within view of many fishing vessels in his three-hour trek to Nova Scotia. After flying over the Gulf of Maine he sighted land before noon and climbed to 200 feet. His landmarks told him that he was only two degrees (six miles) off course.

At the northern end of Nova Scotia, he flew through a few storm clouds, but his route soon took him away from the approaching front and across the ice-caked oceans. By six o'clock that evening he was flying along the southern coast of Newfoundland. Taking his bearings, Lindbergh flew over St. Johns, "so there would be no question of that fact that I had passed Newfoundland in case I was forced down in the North Atlantic."

Fatigue had set in several times between Long Island and Newfoundland...it had already been more than 30 hours since the young pilot had last slept. The situation only worsened as darkness fell twelve hours after his departure. Storm clouds and heavy fog blanketed the angry Atlantic below the Spirit of St. Louis and Lindbergh climbed to 10,000 feet. Ice formed on the wings as he flew through a thunderhead, forcing him to turn back and make a circuitous route around the dangerous storm. Despite the chill, Lindbergh kept the window of his airplane open to help him stay awake. Boredom and fatigue were taking an increasing toll on his mind and body.

Saturday, May 21, 1927

Lindbergh's eastward course brought dawn at what would have been close to 1 a.m. New York time. It was now Saturday, May 21 in Paris. The light of the sun brought some relief to tired eyes, and as the warming air opened holes in the fog, Lindbergh dropped down to 200 feet above the oceans.

Those early morning hours of the flight were filled only with intermittent glimpses of the angry ocean below, before another bank of fog enveloped man and machine. It became among the most difficult and dangerous hours of the flight. Again and again, Lindbergh found himself falling asleep, eyes open but mind shutting down. By 7:52 a.m. he had been 48 hours without sleep, airborne for twenty-four hours, and with nothing but a deadly ocean beneath him. Time and again he had seen shorelines in the distance "with trees perfectly outlined against the horizon...the mirages were so natural that, had I not been in mid-Atlantic and known that no land existed along my route, I would have taken them to be actual islands."

Fortunately, after that initial 24-hour period, Lindbergh got his second wind and began watching the horizon in anticipation of a break in the scenery. Two hours later the first fishing boats began to appear on the waters below. Flying over the first, he saw no signs of life and moved on to the next. As he circled it a face appeared at the cabin window. Cutting back on his engine to decrease the noise, Lindbergh flew closer and yelled through the window of his airplane, "Which way is Ireland?" When he was unable to get a response, he straightened out and headed back on course. An hour later he knew where Ireland was...he was directly over Dingle Bay at the southern tip of the island...less than three miles from the route he had mapped weeks earlier while in San Diego. Glancing at his watch he noted that it was 10:52 a.m. in New York (3:00 p.m. local time). He was two-and-a-half hours ahead of schedule.

Charles Lindbergh had safely negotiated the North Atlantic, and that realization revitalized his weary mind and body. With luck, he might reach the coast of France before darkness fell once again. He increased his airspeed to 110 mph and soon was winging his way over England, across the channel, and then Cherbourg, France. In New York, it was now nearly three in the afternoon, eight in the evening in Paris, two-hundred miles distant. The only thing traversing Europe faster than the Spirit of St. Louis was the news that the daring American pilot was on his way.

It was nearly 10 p.m. local time when Lindbergh spotted the lights of Paris. He circled the Eiffel Tower at four thousand feet, then looked around for the landing strip at Le Bourget Field. Fifteen minutes later he was flying low over the field, identified easily by a long line of hangars. He also noticed all roads into the airfield were filled with cars. At 10:22 p.m. Paris time, the Spirit of St. Louis taxied to a stop and an adoring crowd of thousands of Parisians was rushing towards the silver airplane in a friendly but frenzied mob. Lindbergh quickly cut the switch to his engine to halt the propeller and prevent it from killing someone.

Back in New York it was 4:22 p.m. Charles Lindbergh, the unknown airmail pilot from St. Louis had done what no man had done before. Alone, in 30 hours and 30 minutes, he had flown from New York to Paris.

The world had suddenly become a much smaller planet, and a true world hero had been born.

Earlier concerns about French animosity after the tragic flight of Captains Nungesser and Coli proved totally unfounded. Charles Lindbergh was welcomed at Le Bourget Airfield like few heroes in history have been welcomed. For half-an-hour, the adoring crowd carried him on its shoulders, and the exhausted American airman might not have slept for even more days but for the resourcefulness of some French military pilots. These managed to get their hands on Lindbergh's flight helmet, place it on the head of a nearby American correspondent, and then shouted "Here is Lindbergh". As the crowd rushed over to hail a new world hero, the REAL Charles Lindbergh was secreted off to the American Embassy where he would be the guest of Ambassador Herrick until his departure.

The French allowed the world's newest hero a night of well-earned rest before clamoring for his attention. The morning after his historic flight he appeared with Ambassador Herrick on the balcony of the American Embassy to greet the crowds. Already he was wearing the first of several high honors to be presented to him, the French Cross of the Legion of Honor, bestowed earlier that day the President of the Republic of France. Next, the Aero Club of France presented the young man with its Gold Medal and he was feted with lunch by the American Club. The United States flag was flown over the Chamber of Deputies in honor of Charles Lindbergh, setting a historic precedent. Ambassador Herrick introduced the shy 25-year-old as "America's present ambassador" and his winning smile and charismatic personality quickly made him America's Ambassador to the world. In St. Louis the Star reported:

The French allowed the world's newest hero a night of well-earned rest before clamoring for his attention. The morning after his historic flight he appeared with Ambassador Herrick on the balcony of the American Embassy to greet the crowds. Already he was wearing the first of several high honors to be presented to him, the French Cross of the Legion of Honor, bestowed earlier that day the President of the Republic of France. Next, the Aero Club of France presented the young man with its Gold Medal and he was feted with lunch by the American Club. The United States flag was flown over the Chamber of Deputies in honor of Charles Lindbergh, setting a historic precedent. Ambassador Herrick introduced the shy 25-year-old as "America's present ambassador" and his winning smile and charismatic personality quickly made him America's Ambassador to the world. In St. Louis the Star reported:

"He (Lindbergh) has done more to create a good feeling and increase the prestige of the United States in Europe, recently at low ebb, than any American since George Washington."

Before departing France on May 28, Lindbergh paid a visit to the families of Captains Nungesser and Coli, then flew his now-famous silver airplane to Brussells where he was personally welcomed by King Albert. The King pinned the Knighthood of the Order of Leopold on his chest, making him the first foreigner to ever received the highly coveted award.

From Brussels to London, Lindbergh was received and honored by all of Europe's royalty. At Buckingham Palace, the King presented him with the Air Force Cross. A short time later on his return to Paris, Lindbergh was presented with a medal worn only by members of the famous World War I Lafayette Escadrille. Lindbergh took it all in stride, unspoiled by all the attention, and intent on enjoying an extended tour of Europe. At home, President Calvin Coolidge wanted America's ambassador without portfolio to return. The Spirit of St. Louis was crated up, and the two world travelers returned home aboard the American cruiser Memphis.

"Gentlemen, 132 years ago Benjamin Franklin was asked: 'What good is your balloon? What will it accomplish?' He replied: 'What good is a new born child?'

"Less than twenty years ago when I was not far advanced from infancy M. Bleroit flew across the English Channel and was asked, 'What good is your aeroplane? What will it accomplish?' Today those same skeptics might ask me what good has been my flight from New York to Paris.

"My answer is that I believe it is the forerunner of a great air service from America to France, America to Europe, to bring our peoples nearer together in understanding and in friendship than they have ever been."

June 13, 1927

Charles Lindbergh returned to New York to a reception line none ever before witnesses. Already he had been feted in Washington, DC, welcomed by the President, and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The parade in New York City, replete with a snowstorm of ticker-tape, was witnessed according to one newspaper, by as many as 4 million Americans. Later the Street Cleaning Commissioner reported that it took 110 trucks and 2,000 "white wings" to clean up the streets.

Charles Lindbergh returned to New York to a reception line none ever before witnesses. Already he had been feted in Washington, DC, welcomed by the President, and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The parade in New York City, replete with a snowstorm of ticker-tape, was witnessed according to one newspaper, by as many as 4 million Americans. Later the Street Cleaning Commissioner reported that it took 110 trucks and 2,000 "white wings" to clean up the streets.

Lindberg's reaction was typical of the atypical hero:

"I wonder if I really deserve all this!"

Deserved or not, the moment was Lindbergh's. The Providence Journal reported that it doubted "Any many of any age in the world's history has ever been the recipient of such adulation and such honors as have been heaped upon this youth of twenty-five in the last few weeks." Perhaps the reasons behind it were more accurately surmised in the Jersey City Journal: "Lindbergh's actions in the cockpit of the airplane were heroic, his utterances on land, when he faced adulation unequaled, were the utterances of a hero who is as well-balanced in speech as he is adroit in his manipulations of the airplane."

The bottom line was simply that Charles Lindbergh was a truly good man, a man of courage and imagination, a man of both dream and determination. When unprecedented honor was heaped upon him in Europe, he did not revel in his own accomplishment but saw the praise tendered him as a tribute to his country. When he returned to the praise of his own people, he remained the same simple, humble man he had been before his historic flight. President Coolidge perhaps spoke perhaps the most accurate summary of Charles Lindbergh when he said:

"The absence of self-acclaim, the refusal to become commercialized, which has marked the conduct of this sincere and genuine exemplar of fine and noble virtues, has endeared him to everyone. He has returned unspoiled."

The Guggenheim Tour

In December 1925, millionaire and aviation advocate Daniel Guggenheim created the $2.5 million Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics in order to speed the development of civil aviation in the United States. On June 4, 1927, while Charles Lindbergh was returning home, Guggenheim opened the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics at New York University. On July 20, under the auspices and support of the Fund for Promotion of Aeronautics, Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis began a tour of the United States. Over the next several months, America's newest hero visited all 48 states, making eighty-two stops over an area of 22,000 miles. In cities from coast to coast, he gave 147 speeches and rode in parades equaling 1,290 miles. Everywhere he went, Charles Lindbergh was admired and greeted like no American in history. Humbly the young man accepted his new role, not for his own glory, but to promote aviation. His influence paved the way for many new advances. It also had a profound impact on those who saw him. The twelve-year-old son of one South Dakota farmer later wrote of his own experience during this time.

Sioux Falls, SD - August 27, 1927

The Guggenheim Tour ended where it began, Mitchell Field, on October 23. Lindbergh spent a month at the estate of Daniel Guggenheim, writing his much-anticipated autobiography...simply titled "We." In it the American hero wrote simply and honestly about his family, his interest in aviation, his military training, and his airmail days. His account of the trans-Atlantic flight comprised little more than a single chapter, expressed with just the facts and no embellishment. When it became necessary, for the sake of recording history, to relate the honors and praise bestowed upon him for his accomplishment, the still humble Lindbergh opted to have his friend Fitzhugh Green related it in a third-person narrative. No success could spoil the simple humility of this truly great American.

On December 14, 1927, the United States Congress authorized a special award of the Medal of Honor to Army Captain Charles A. Lindbergh. It was presented by President Coolidge and would remain perhaps the most controversial award of our Nation's highest military Medal in its distinguished history. Despite that controversy, surfacing only in later years and for all the wrong reasons, Charles Lindbergh was indeed a hero. Only three Army Airmen to that date had earned Medals of Honor, all during World War I and all of them posthumously. (Eddie Rickenbacker's Medal of Honor was not presented until 1930.) Thus Charles Lindbergh became the first living airman to receive his Nation's highest honor.

On December 14, 1927, the United States Congress authorized a special award of the Medal of Honor to Army Captain Charles A. Lindbergh. It was presented by President Coolidge and would remain perhaps the most controversial award of our Nation's highest military Medal in its distinguished history. Despite that controversy, surfacing only in later years and for all the wrong reasons, Charles Lindbergh was indeed a hero. Only three Army Airmen to that date had earned Medals of Honor, all during World War I and all of them posthumously. (Eddie Rickenbacker's Medal of Honor was not presented until 1930.) Thus Charles Lindbergh became the first living airman to receive his Nation's highest honor.

That same month the American ambassador to Mexico requested that Lindbergh make a goodwill tour of several South American nations on behalf of the United States. Everywhere Lindbergh went, the people loved him, and for his own part, the shy young man with a captivating smile did not mind being used for the greater good of his own country. It was a fortunate goodwill tour indeed, for in it Charles Lindbergh would find a new kind of love.

The American Ambassador in Mexico was a well-known and highly regarded man, Dwight Whitney Morrow--the same man who two years earlier had headed up the Morrow Board that had been so instrumental in the subsequent changes in the American Air Service and its new role as the American Air Service. Morrow's 21-year-old daughter Anne was a pretty, bright, but unusually shy young woman aspiring to e a writer. During Lindbergh's goodwill tour, she fell madly in love with America's most eligible bachelor. That was not unusual, nearly all of the single girls of the United States had fallen in love with the tall, handsome hero with an engaging smile and humble personality. What made this different was that this time, the hero also fell in love with the young woman who adored him.

Early in 1928 Lindbergh completed his Latin American tour and returned home. On April 30 he flew Spirit of St. Louis from Lambert Field in St. Louis to Bolling Field in Washington, DC. It was the last flight of the most famous airplane in history, retired after 789 hours, 28 minutes of flight.

That same spring Anne Morrow graduated from Smith College, and the following year she and Charles were married. Charles went to work for Transcontinental & Western Air (later Trans World Airlines) which he was instrumental in founding and flew extensively to establish new air routes. Anne usually accompanied him as a passenger, becoming an avid aviatrix herself. In January 1922 she piloted a glider near La Jolla, California, and became the tenth person and first woman in the United States to earn a first-class glider license. Six months later on June 22, 1930, the couple's first child was born, Charles Lindbergh, Jr.

That same spring Anne Morrow graduated from Smith College, and the following year she and Charles were married. Charles went to work for Transcontinental & Western Air (later Trans World Airlines) which he was instrumental in founding and flew extensively to establish new air routes. Anne usually accompanied him as a passenger, becoming an avid aviatrix herself. In January 1922 she piloted a glider near La Jolla, California, and became the tenth person and first woman in the United States to earn a first-class glider license. Six months later on June 22, 1930, the couple's first child was born, Charles Lindbergh, Jr.

In 1931 Anne Morrow Lindbergh earned her own pilot's license and joined her husband in a historic flight through Canada, Hudson's Bay, Alaska, and across the Bearing Sea to open-air routes to the Orient. The couple sailed to Shanghai when their Sirius was damaged in October, then cut short their travels to return home to bury Anne's father.

In 1931 Anne Morrow Lindbergh earned her own pilot's license and joined her husband in a historic flight through Canada, Hudson's Bay, Alaska, and across the Bearing Sea to open-air routes to the Orient. The couple sailed to Shanghai when their Sirius was damaged in October, then cut short their travels to return home to bury Anne's father.

The greater tragedy lay ahead in the following year. On March 1, 1932, Lindbergh's son was kidnapped. Ten weeks later the 19-month old boy's decomposing body was discovered, and the nation mourned along with the dream couple who to this point, seemed to have everything going for them. The subsequent trial and execution of Bruno Hauptmann, the accused kidnapper/murder, was called The Trial of the Century and became almost a media circus. For the Lindberghs, life would never be the same again.

The birth of Jon Lindbergh in 1932 though a source of joy to Charles and Anne, could never replace the sense of grief in the loss of their first-born. The two found some relief in their 1933 flights that ranged from Europe to South America, adventures dutifully recorded by Anne in her diary for later publication. (In all Anne would write and publish 13 books, including five diaries.)

The birth of Jon Lindbergh in 1932 though a source of joy to Charles and Anne, could never replace the sense of grief in the loss of their first-born. The two found some relief in their 1933 flights that ranged from Europe to South America, adventures dutifully recorded by Anne in her diary for later publication. (In all Anne would write and publish 13 books, including five diaries.)

The five years of exploration accomplished by Charles and Anne did much to pave the way for advancements in aviation, but memories of the kidnapping and murder could not escape them, nor could they escape the incessant prying of the media into their private lives. In 1935 the Lindbergh family moved to England to seek both solitude and safety.

The Albatross

Americans have always loved a success story. Ordinary people achieving extraordinary heights against insurmountable odds tend to remind us that in The Land of Opportunity, anything is possible. Our heroes give us hope that someday WE might achieve that of which we dream. Sadly, if Americans love anything more than a success story, it is the scandal that ultimately brings those heroes back down to our own level. Such would be the case with the man who had become perhaps the most lauded American hero in our Nation's brief history. For Charles Lindbergh, that scandal resulted from two personal character traits: a dedication to his country that demanded he answer his Nation's call to duty, and a sincere honesty to speak the truth, regardless of the consequences.

In 1936 the German government invited Charles Lindbergh to inspect their air establishments. With urging from Major Truman Smith, the American attaché in Berlin to comply in order to report back on the condition of German airpower, Lindbergh went. It was the first of five trips, each of which greatly impressed him with the German efforts to build an efficient and powerful air force. During Lindbergh's visit in 1938, Hermann Goering presented Colonel Lindbergh with the Verdienstkreuz der Deutscher Adler for his "services to aviation of the world and particularly his historic 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic." In presenting its highest national honor to Lindbergh, Germany did no more than any other European nation had already done to honor the man. In the months that followed, however, Lindbergh's acceptance of the medal became a subject of great controversy to the point that Anne Lindbergh referred to the decoration as "the Albatross".

Colonel Lindbergh, still a member of the Army Air Service Reserves, was certainly impressed by the powerful German Luftwaffe. When asked to rate the air forces of the world, he spoke what he believed to be the truth: "Germany number one. Great Britain number two." It was not a message Americans wanted to hear, or believe, and Lindbergh's frank honesty coupled with the Albatross began raising serious questions about his loyalty as an American.

In 1939 as the war was brewing in Europe, the Lindberghs moved back to the United States. Lindbergh's inspection tours had impressed him with the efficiency of the German air force...but it had also frightened him...not for himself but for his country. He honestly believed that the American Air Service had been so neglected as to be greatly inferior to the forces being established in Germany. In his journal he wrote:

"There are wars worth fighting, but if we (the United States) get in this one, we will bring disaster to the country and possibly our entire civilization. If we get into this war and really fight, nothing but chaos will result...it won't be like the last, and God knows what will happen here before we finish it."

The American hero of a decade past was not alone in this belief. At the time of his return home, nine out of ten Americans were opposed to the United States getting involved in the war brewing in Europe. Even former president Herbert Hoover spoke in opposition. But when Charles Lindbergh began voicing his own opposition, he became an enemy of the White House. Lindbergh was recruited by Montana Senator Burton Wheeler in an organization called "America First". The group's philosophy was that events unfolding in Europe were Europe's problems. The United States should concentrate on policies that strengthened and protected America first, not on the rest of the world. Lindbergh sincerely believed in that credo and became a key spokesman for the group. Because of this, Lindbergh was soon being portrayed as anti-Semitic (he was in fact, honestly critical of some practices that lent credence to this charge, though Lindbergh deplored the treatment of the Jews by Nazi Germany and said so).

The American hero of a decade past was not alone in this belief. At the time of his return home, nine out of ten Americans were opposed to the United States getting involved in the war brewing in Europe. Even former president Herbert Hoover spoke in opposition. But when Charles Lindbergh began voicing his own opposition, he became an enemy of the White House. Lindbergh was recruited by Montana Senator Burton Wheeler in an organization called "America First". The group's philosophy was that events unfolding in Europe were Europe's problems. The United States should concentrate on policies that strengthened and protected America first, not on the rest of the world. Lindbergh sincerely believed in that credo and became a key spokesman for the group. Because of this, Lindbergh was soon being portrayed as anti-Semitic (he was in fact, honestly critical of some practices that lent credence to this charge, though Lindbergh deplored the treatment of the Jews by Nazi Germany and said so).

On April 25, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt publicly attacked Lindbergh in a press conference, going as far as to label the man treasonous and questioning his commission in the U.S. Air Service Reserves. Reportedly, there was even talk of stripping Lindbergh of his Medal of Honor. On Sunday, April 27 Lindbergh wrote in his journal:

"Have decided to resign. After studying carefully what the President said, I feel it is the only honorable course to take. If I did not tender my resignation, I would lose something in my own character that means more to me than my commission in the Air Corps. No one else might know it, but I would. And if I take this insult from Roosevelt, more, and worse, will probably be forthcoming."

The following morning Colonel Charles Lindbergh performed one of his most difficult and most courageous acts. He submitted his letters of resignation to the President and to Secretary of War Henry Stimson. In the months that followed, he spoke, again and again, urging his country to avoid war. As a result, he remained true to his own personal beliefs, and became one of the most hated and misunderstood men in America.

As meteoric as had been the rise of an unknown airmail pilot from St. Louis, so too became the fall of a great hero. More than half-a-century later, Charles Lindbergh is still remembered by many as a war-protestor or a pacifist. All too few know the rest of the story...for everything changed on December 7, 1941.

Sources:

Ault, Phil, By The Seat of their Pants, Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, NY 1968

Cook, Donald, For Conspicuous Gallantry, C.S. Hammond & Company, Maplewood, NJ, 1966

Foss, Joe and Donna, A Proud American, Pocket Books, 1992

Lindbergh, Charles A, WE, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY, 1927

Lindbergh, Charles A, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., New York, NY 1970

Manning, Robert, Above and Beyond, Boston Publishing Company, Boston, MA, 1985

"Why the World Makes Lindbergh Its Hero", The Literary Digest, June 25, 1927

Photo Source for Charles Lindbergh Air Mail Crash - Flickr

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED