Hurricane Katrina

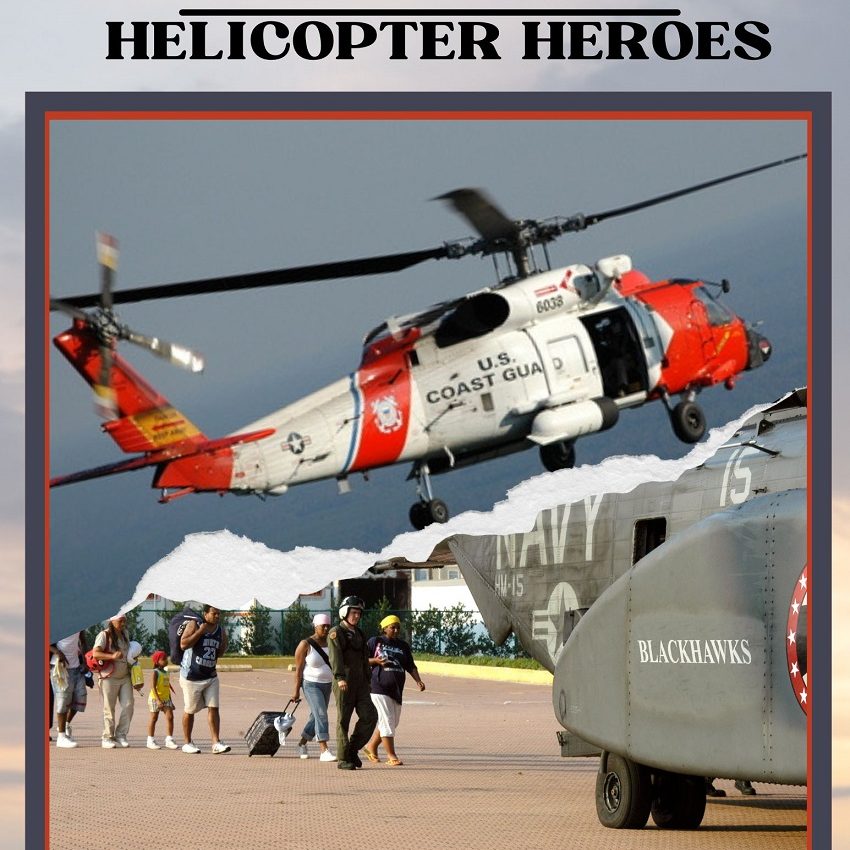

Helicopter Heroes

By James G. Fausone, Esq.

The immensity of Hurricane Katrina in late summer of 2005 is hard to grasp decades later. Hurricanes often start as small tropical waves and depressions. Katrina entered the Gulf of Mexico on August 26 and rapidly intensified to a Category 5 hurricane before weakening to a Category 3 at its landfall on August 29 near Buras-Triumph, Louisiana. Someone has to fly into the storm, jump into the raging flood waters, and conduct air and boat rescues. Who do you call? The United States Coast Guard and its brother, the U.S. Navy. Who will jump into raging water? USCG rescue swimmers.

Natural Disaster of Biblical Proportions

Hurricanes are classified using the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which categorizes them from Category 1 to Category 5 based on their sustained wind speeds. Hurricanes reaching Category 3 and higher are considered "major hurricanes" due to their potential for significant loss of life and damage. A Cat 3 has speeds of 111-129 mph. The damage is often devastating, including well-built framed homes may experience major damage and the removal of roof decking and gable ends. Many trees will be snapped or uprooted, leading to numerous blocked roads. Electricity and water services will be unavailable for several days to a few weeks after the storm passes. Coastal flooding can destroy smaller structures and damage larger ones due to battering from floating debris. Low-lying escape routes can be cut off by rising water. In essence, a Category 3 hurricane brings very significant damage and long-term disruptions.

The path of a hurricane is the major factor in how bad the damage will be on land. As those states bordering the Gulf of America know where landfall is made becomes what to watch on radar and weather reports. When it comes to hurricanes in the Northern Hemisphere, the right-front quadrant is generally considered the worst and most dangerous. This is often referred to as the "dirty side" of the hurricane. In the right-front quadrant, the hurricane's clockwise forward motion combines with the rotational winds. This means the wind speeds are amplified in this section, leading to the strongest sustained winds. The stronger winds in the right-front quadrant push a greater volume of water ahead of the storm, leading to the highest storm surge. This can result in catastrophic coastal flooding, which is often the deadliest aspect of a hurricane. This quadrant is also the most prone to spawning tornadoes embedded within the hurricane's rainbands.

Katrina hit and its impact was felt most in New Orleans, although the City was not directly hit. But the significant storm surge it generated, particularly from Lake Pontchartrain, caused catastrophic levee failures and widespread flooding, submerging 80% of the city. The Mississippi Gulf Coast bore the brunt of the Category 3 winds and an immense storm surge, with some areas experiencing surge heights of 24-28 feet.

New Orleans, the Crescent City, is surrounded by Lake Pontchartrain. It is the combination of Katrina and the breaching of the levees protecting New Orleans from the lake which it sits below that amplified the devastation. The failure of the walls was not unexpected, but not anticipated. Numerous investigations by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers pinpointed several key reasons for these failures, revealing a complex interplay of engineering flaws, design shortcomings, and a "system in name only." The levees were compacted soil which were weakened by time and rain. In hindsight, the structural problems which were known were not addressed because of underfunding of maintenance and improvement projects for the New Orleans levee system. While the primary cause of failure was design and construction flaws, insufficient funding may have exacerbated some vulnerabilities and delayed necessary upgrades.

The Impact

Hurricane Katrina caused 1,392 fatalities and damages estimated at $125 billion. It impacted millions of people in a variety of ways, from direct damage and displacement to widespread economic and social disruption. Approximately 1.2 to 1.5 million people were covered under voluntary or mandatory evacuation orders, primarily in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, before the storm hit.

Despite mandatory evacuation orders in New Orleans, an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 individuals remained in the city during the storm, many of whom became trapped by the flooding. More than one million housing units were damaged or destroyed in the Gulf Coast region, with about half of these in Louisiana. In New Orleans alone, 134,000 housing units (70% of all occupied units) were damaged. Approximately 2.5 million power customers in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama experienced outages.

Emergency Response to Katrina

Prior to landfall, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) began pre-positioning resources in a ring around the expected impact zone and activated more than 400 reservists. On August 27, 2005, it moved its personnel out of the New Orleans region prior to the mandatory evacuation. Aircrews from the Aviation Training Center, in Mobile, staged rescue aircraft from Texas to Florida. The USCG crews and aviation resources became involved in a round-the-clock rescue effort in New Orleans, and along the Mississippi and Alabama coastlines.

When the hurricane’s wind and storm surge hit, the New Orleans area was swamped. The extensive flooding surprised many with people stuck on roofs of houses and in the Superdome. This type of natural disaster knocks out electricity, phone service, fresh water, food distribution, sewer and roads. The waters ripped apart and released chemical tanks, petroleum tanks, and destroyed public health systems. Pets, animals and people were displaced and desperate. Tempers flared and normally civil people turned angry and scared.

In total, the Coast Guard rescued over 33,500 people, including 6,500 by helicopter, making it the largest air rescue operation in its history. These missions were often carried out under extreme conditions—urban flooding, downed power lines, and even armed civilians.

USCG leaned primarily on two main helicopter types during the Hurricane Katrina response: HH-65 Dolphin and the MH-60 Jayhawk. The Dolphin is a smaller, short-range helicopter, and was crucial for search and rescue operations, particularly in urban areas and for lifting survivors from rooftops and flooded buildings. The Jayhawk, a larger, medium-range helicopter, was used for search and rescue as well as other missions, including transporting supplies and personnel over longer distances.

The USCG also deployed other aircraft like HC-130s for various purposes like logistics, communication, and dropping survival rafts. In total, over 40 Coast Guard helicopters were involved in the rescue and recovery efforts, alongside other military and civilian helicopters that arrived to assist. The HH-65 Dolphin was particularly notable for making the first rescue within hours of the storm's landfall.

Equipment is only as good as the personnel deployed. Along with pilots and maintenance crew, an integral part of the USCG disaster effort is the use of rescue swimmers. If you think jumping out of a perfectly good aircraft is crazy, then jumping out of a hovering helicopter into unknown waters is bonkers!

Coast Guard rescue swimmers helped save over 3,000 people during the Katrina response. They were essential to the Coast Guard's overall rescue effort. Rescue swimmers are an integral part of the helicopter rescue team. They operate in difficult conditions, jumping from helicopters into rough seas or flooded areas. These jumps are always high-stress and dangerous.

Who are these Rescue Swimmers?

USCG rescue swimmers, officially known as Aviation Survival Technicians (ASTs), undergo some of the most rigorous and demanding training in the U.S. military. Their job requires exceptional physical fitness, mental resilience, and a broad range of technical and medical skills. Candidates must pass an incredibly challenging initial physical fitness test. General physical fitness, as defined by running and calisthenics, includes: specific fitness tests for swimming and water confidence are a must. Beyond physical prowess, candidates are assessed for their ability to perform under pressure, demonstrate strong problem-solving skills, and exhibit mental resilience in extremely stressful situations, especially in the water.

Once they make it past the basics, they go off to “A” School for Aviation Survival Technician (AST). This intensive course typically lasts around 22-24 weeks. The core curriculum includes Advanced Water Survival and Rescue Techniques. Swimmers learn a vast array of techniques for rescuing individuals in various challenging maritime environments (rough seas, strong currents, cold water, debris fields). Then it is on to the mechanics of helicopters: mastering techniques for deployment from and recovery by helicopters, often involving jumps from significant heights into turbulent water; becoming proficient in the use of hoist systems to bring survivors and themselves into the aircraft; expertise in using rescue baskets, litters, harnesses, and other specialized equipment; learning techniques to safely approach, calm, and secure uncooperative or panicked individuals in the water; buddy breathing/towing drills; Aviation Life Support Equipment (ALSE) Maintenance; and Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) training.

The attrition rate for USCG rescue swimmer training is notoriously high (often 70-85%), a testament to the extreme physical and mental challenges involved. Those who graduate are among the most capable and dedicated rescue professionals in the world, embodying the Coast Guard's swimmer’s creed, "So Others May Live." The majority of graduates are men and there are generally about 350 active-duty rescue swimmers at any time. The 2006 movie “The Guardian” starring Kevin Costner and Ashton Kutcher highlights this unique and rigorous training.

Individual rescue swimmers demonstrated exceptional bravery and skill during the Katrina response, such as Aviation Survival Technician 2nd Class (AST2) Sara Faulkner, who rescued 48 people in a single 12-hour shift. Another dramatic rescue came from a crew flying out of Houma, Louisiana, Lt. Dave Johnson, Lt. Craig Murray, Petty Officer 2nd Class Warren Labeth, and Petty Officer 3rd Class Laurence Nettles responded to a mayday call from a woman stranded with her daughter and 4-month-old grandchild. Their 1876-era home had flooded to the second floor, forcing them onto the roof. The crew made them their first rescue of the day and went on to fly nine straight days of missions, saving countless others.

Another standout mission involved rescue swimmer Wil Milam, who was dropped into pitch-black floodwaters near a warehouse outside New Orleans. His helicopter flew off, leaving him alone, so he could better hear cries for help. Using night-vision goggles, he located a man and four dogs and hoisted them to safety. The man’s pig, however, had to stay behind. Milam, 39 at the time, had never been outside Alaska for the USCG. He had never done urban search and rescue before and was only familiar with ocean rescues. Milam experienced floating caskets at a cemetery, alligators and trailer park rescues. He is quoted as saying “Man, they didn’t teach me this in swimmer school!”

After Katrina, in the spring of 2006, CAPT Bruce Jones, commanding officer of Air Station New Orleans, and CAPT Frank Paskewich, commander of Coast Guard Sector New Orleans, presided over a ceremony at the air station in Belle Chasse where more than 115 personnel received medals and awards for heroism, including the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal, for their hurricane response efforts during Hurricane Katrina operations. CAPT Jones wanted to recognize the efforts of his men and women during Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath, which was the largest life-saving effort in Coast Guard history.

Awards for an Incredible Job Well Done

Thousands of rescuers from government and nongovernmental agencies participated in this effort, including more than 5,600 men and women from the Coast Guard. The agency deployed 26 cutters, over 40 helicopters, 14 fixed-wing aircraft, 13 auxiliary aircraft, 119 boats, and eight Marine Safety and Security Teams and Disaster Assist Teams. The men and women were recognized by a variety of individual and unit awards.

The highest medals awarded to those helicopter heroes were the Coast Guard Medal and the Navy & Marine Corps Medal. The Coast Guard Medal is awarded for distinguishing themselves by heroism not involving actual conflict with an enemy. For the decoration to be awarded, an individual must have performed a voluntary act of heroism in the face of great personal danger or of such a magnitude that it stands out distinctly above normal expectations.

USCG rescue swimmer Robert R. Williams was awarded the Coast Guard Medal. On September 1, 2005, he was deployed aboard a Coast Guard HH-65B helicopter to rescue over 150 stranded flood victims from the roof of a hotel near Lake Pontchartrain. During the mission, Williams was confronted by three armed men who threatened him, demanding to be rescued first. Despite the danger, he stood his ground, established a recovery order based on need, and ensured the safe evacuation of injured victims before dealing with the armed individuals. He later convinced them to relinquish their weapons and board the helicopter, helping to defuse the tense situation. Williams went on to perform over 150 rescues during the disaster and was awarded the Coast Guard Medal for his exceptional bravery and dedication.

Robert R. Williams' citation reads:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Coast Guard Medal to Aviation Survival Technician Third Class Robert R. Williams, United States Coast Guard, for heroism on the evening of 1 September 2005 while serving as Rescue Swimmer aboard Commanding General-6539, a Coast Guard HH-65-B helicopter. In the aftermath of Hurricane KATRINA, the levee system in New Orleans was breached, flooding the city and causing a major evacuation of the metropolitan area. Commanding General-6539 was dispatched to conduct rescue efforts for over 150 remaining flood victims stranded on the roof of the Day’s Inn in Lake Front near Lake Pontchartrain. Petty Officer Williams was fully briefed on the situation’s volatility prior to deploying to the hostel roof. As he disconnected from the hoist, three men brandishing knives and claiming to have a gun accosted and threatened to kill him if they were not rescued first. Without regard for his own safety, Petty Officer Williams heroically faced down the men, stated his rescue priorities and threatened the use of his survival knife to gain control of the situation. He established a recovery order based on need and sent six injured victims to the helicopter waiting above, opting to remain on the hotel roof with the armed men as Commanding General-6539 departed to rescue the injured survivors. He continued to establish order and diffuse the situation, assuring everyone they would leave the roof before he did. When Commanding General-6539 returned, Petty Officer Williams convinced the men to relinquish their weapons and be hoisted aboard the helicopter, greatly reducing tension levels on the roof. He then worked with four other helicopters to evacuate the remaining victims, rescuing over 150 flood victims from the hotel, and was the last one off the roof. Petty Officer Williams went on to perform 15 other direct deployment rescues that day and 113 in all. Petty Officer Williams demonstrated remarkable initiative, exceptional fortitude, and daring in spite of imminent personal danger in this rescue. His courage and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Coast Guard.

The following tales are just a few of the other amazing Coasties that answered the call to save and protect their fellow countrymen. They certainly lived up to their motto - Semper Paratus - Always Ready. There are 30 Coasties who received the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for work during Katrina. The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded to Coast Guard members who perform acts of heroism or extraordinary achievement while flying. It is the highest award in the United States for aerial achievement. United States for aerial achievement.

The following are some of the most amazing stories of those who received this award.

Lieutenant Thomas F. Cooper, while serving as Aircraft Commander aboard Coast Guard HH-65B helicopters in response to Hurricane KATRINA. He saved numerous survivors from treacherous conditions during 15 sorties, totaling over 29 day-and-night flight hours, including 13 hours as a single pilot. He adeptly hoisted a pregnant woman from a small, constricted balcony, the first rescue in metropolitan New Orleans. Most notably, he completed a pinpoint vertical rescue swimmer pick-up of a 400-pound, non-ambulatory survivor directly from her second-story bed through the damaged rafters and roof.

Lieutenant Jason J. Dorval located an elderly quadriplegic man and two of his family members stranded by raging floodwaters. Battling strong turbulence, he safely hoisted the three survivors through the dark and tangled wreckage of downed power lines, trees, and storm debris, and transported them back to Mobile for medical care. Returning to the scene amid the deepening catastrophe, Lieutenant Dorval found and hoisted a heart attack victim from the rubble of a destroyed casino and delivered him to a nearby hospital for care. After levees in New Orleans had broken and flooded 80% of the city, leaving thousands of residents stranded, Lieutenant Dorval and his crew proceeded to New Orleans and courageously performed rescue missions in an unfamiliar, unit, and dangerous area of operations.

Lieutenant Commander Brian E. Hudson operated as aircraft commander for over 33 day-and-night flight hours, saving 98 survivors from the floodwaters and collapsed structures spread throughout metropolitan New Orleans. With search efforts hampered by low visibility and an unprecedented level of conflicting air traffic, Lieutenant Commander Hudson located 29 survivors trapped in a flooded three-stop' apartment complex, desperately signaling for rescue from windows and balconies. Unable to deliver the rescue basket to the obstructed windows, Lieutenant Commander Hudson guided his crew through a series of 29 rescue swimmer deployments to the apartment balconies, rescuing all survivors. Later, Lieutenant Commander Hudson spotted a flooded elementary school with over 200 survivors in need of evacuation. Marshaling and coordinating a multitude of air assets on scene, Lieutenant Commander Hudson initiated the recovery of all 200 survivors, personally recovering 27 victims from perilous conditions.

Lieutenant David M. Johnston served as Aircraft Commander on HH-65B helicopters during 22 sorties, totaling over 39 day-and-night flight hours. He responded to a desperate mayday, locating two adults and a premature infant in a boat lodged under trees in floodwaters, where he adeptly maneuvered into a high hover, in 65 knot wind gusts and turbulence. When severe down drafts forced the aircraft toward obstacles and wind gusts entangled the hoist cable, he directed his crew to free the cable successfully, saving the three survivors. Working northward, Lieutenant Johnston and his crew rescued 43 individuals from rising waters and established the first survivor collection point to expedite rescue operations, where he judiciously deployed his rescue swimmer to act as an on-scene commander.

Aviation Survival Technician Third Class Mitchell A. Latta, battling 40 knot winds and flying debris, was deployed to a rooftop where 10 survivors gathered inches above rising floodwaters. One survivor was an amputee suffering from diabetic shock trapped helplessly in her attic. Using a sledgehammer, Petty Officer Latta demolished the roof and located the survivor, who was too large to be moved. Displaying exceptional ingenuity, he attached a quick strap to the survivor and coordinated with his flight mechanic to winch the 400-pound survivor out of the house. Later, he discovered a paralyzed stroke victim trapped in her attic. While balanced precariously on thin wooden beams, he signaled to hoist the survivor, cautiously protecting her from broken boards and nails as she was carefully maneuvered through the hole in the roof. His actions, skill, and valor were instrumental in the rescue of 181 storm victims.

Chief Aviation Survival Technician Martin H. Nelson deployed to an unimaginable scene of chaos, where 200 desperate survivors suffering from three days of severe exposure to intense heat, lacking food and water, congregated on the roof of a school, demanding evacuation. Despite nearby gunshots, visible muzzle flashes from below, and a volatile crowd, Chief Petty Officer Nelson remained on scene until survivors were saved.

Commander James S. O'Keefe was awarded a Gold Star for his DFC. Commander O'Keefe flew over 29 days and night flight hours. He went directly to the Superdome, where he chose the only available spot and assigned each crew member a specific obstacle to watch as he expertly landed between two turning H60 helicopters to evacuate seven critical patients. His crew subsequently rescued a 550-pound critically ill patient during a hoisting and hovering evolution that lasted over one hour. Commander O'Keefe then served as a model of flight expertise as he inserted an eight-person SWAT team into the Superdome parking lot, subduing the riotous activities and bringing order to the volatile crowd. Commander O'Keefe then recovered a survivor suffering kidney failure, boldly landing between two buildings and clearing the structures by only feet. On 1 September, Commander O'Keefe bravely accepted the mission to reconnoiter a hospital where shots had been fired. Discovering over 200 patients and staff requiring immediate evacuation, Commander O'Keefe took charge and rallied two additional helicopters to assist. Commander O'Keefe not only acted as on-scene commander for the operation but also completed 60 hoists on night vision goggles while surrounded by hazards and obstructions. On 3 September, Commander O'Keefe participated in the massive evacuation of the New Orleans convention center, transiting a flight corridor packed with dozens of rescue aircraft. Commander O'Keefe's actions, aeronautical skill, and valor were instrumental in the rescue of 214 storm victims. His courage, judgment, and devotion to duty are most heartily commended and are in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Coast Guard.

Aviation Survival Technician Third Class Aaron G. Raines served as a rescue swimmer for 18 flight hours, performing urban search and rescue. After hoisting 21 survivors from 15 separate homes, Petty Officer Raines deployed to an inundated apartment complex where he located a diabetic woman suffering an insulin imbalance. Knowing she required immediate medical attention, he delicately coaxed the delusional and combative woman to the rooftop and into the rescue basket, then kept her stable en route to a medical facility. Raines' actions and skills were instrumental in the rescue of 113 lives.

Lieutenant Olav M. Saboe saved 143 survivors from treacherous conditions during 17 sorties totaling 30 day-and-night flight hours. He expertly conducted 57 night hoists, making rescues from balconies, porches, second-story windows, and rooftops, precisely hovering between trees and power lines with no safe fly-out options available. Saboe's actions, aeronautical skill, and valor were instrumental in the direct rescue of 143 victims.

Lieutenant Commander William E. Sasser, Jr. flew 40 day-and-night flight hours performing a series of grueling and hazardous rescues. On one mission, he flew his aircraft to extreme limits while rescuing 60 survivors from a school rooftop, maximizing payload on every rescue. For six consecutive days and nights, Lieutenant Commander Sasser's actions, aeronautical skills, and valor were instrumental in the rescue of 160 lives.

Aviation Survival Technician Second Class Joel M. Sayers, flying over 42 hours on day and night search and rescue missions in a hazardous urban disaster environment. He saved the elderly and the sick. With relentless determination, Petty Officer Sayer managed to extricate the man, who had no use of his legs, through a roof hole and hoist him to safety. On August 31st, Petty Officer Sayer saved a family of five from a collapsing carport, leaping across a five-foot gap to a stable garage where a rescue could be made. On one mission, he cut through a 2 x 10-inch beam using a hacksaw to save two elderly invalids trapped in the lower floors. While rescuing an elderly man on ventilation from an adjacent building, Petty Officer Sayer was assaulted by a violent survivor and struck with a bottle. With the utmost composure, he resisted retaliation, calmed the situation, and ultimately rescued the entire family. Petty Officer Sayer's actions, aeronautical skill, and valor were instrumental in the rescue of 68 storm victims.

Petty Officer Jason A. Shepard received a Gold Star instead of a Second DFC. His crew located a couple and their six-month-old baby trapped atop a car and in imminent danger from rising flood waters. Later, he observed literally hundreds of survivors stranded on surrounding rooftops. With heroic perseverance and complete disregard for his own safety, Petty Officer Shepard swam from house to house through the floodwaters, navigating jagged debris and industrial waste. Upon reaching the flooded homes, he fought his way through tangled debris, sometimes scaling walls to climb his way to each rooftop to reach survivors. Adding to the mayhem were 200 volatile and bewildered survivors surrounding him and demanding evacuation. In order to subdue the crowd, he directed the most hostile evacuees to assist withthe care of critical survivors, turning their aggression into a constructive task, and quickly de-escalated the situation.

Helicopter Pilots Are Not Just Ride Share Drivers

The Marines like to joke that the Navy is just Uber or Lyft for the Marines. In reality, the Navy copter pilots do more than just give rides. During Katrina, they responded day and night to calls for assistance in close quarters and dangerous conditions.

The U.S. Navy also played a crucial role in the disaster response to Hurricane Katrina, deploying a significant force including 12 warships, 9 logistic ships, 68 naval aircraft, and 10,000 sailors. Their efforts focused on search and rescue, medical assistance, and logistical support.

The Navy successfully evacuated 16,412 citizens, delivered over 2.6 million liters of water and 17 million pounds of food, and provided medical treatment to over 9,000 patients. They also contributed to reopening the international airport and port facilities. Naval aviation units provided vital logistical support, transporting personnel, supplies, and evacuating hundreds of citizens.

As mentioned, this disaster required the use of Navy helicopter assets as well. The highest award from the Navy for this peacetime effort was the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. It is the highest non-combat decoration awarded for heroism by the US Navy. The medal was established by an act of Congress on 7 August 1942. The Navy and Marine Corps Medal is the equivalent of the Army’s Soldier’s Medal, the Air and Space Forces' Airman’s Medal, and the Coast Guard Medal.

The recipient of the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for Katrina helicopter rescues was Stewart C. Mathews.

Mathews’ citation reads:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy and Marine Corps Medal to Aviation Warfare Systems Operator First Class (Aviation Warfare) Stewart C. Mathews, United States Navy, for heroism while serving as a Helicopter Rescue Swimmer assigned to Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron Light FOUR SIX during search and rescue operations in support of Joint Task Force KATRINA on 2 September 2005. In an extremely dynamic and exhausting search and rescue mission over Louisiana, Petty Officer Mathews displayed bravery and selflessness with tremendous jeopardy to his own safety by risking his life during the search and rescue effort in the wake of Hurricane KATRINA. He deployed to the gabled roof of a flooded two-story home through deadly debris and dangerous power lines, closing to within ten feet of a razor-sharp wind-damaged tree to rescue five stranded civilians, one of which was a bedridden elderly victim. After safely recovering three survivors and using his own body as a shield from the swirling debris, he entered the damaged house through the hole, traversing a structurally unsound attic to locate the bedridden survivor. Displaying a strong presence of mind and using his surroundings, Petty Officer Mathews constructed a makeshift stretcher in order to safely maneuver the survivor back through the unstable attic and through the one-foot by two-foot hole in the roof. Employing the rescue litter, he hoisted the survivor to safety, avoiding downed trees and power lines, and then safely recovered the final survivor. By his courageous and prompt actions in the face of great personal risk, Petty Officer Mathews undoubtedly prevented the loss of several lives, thereby reflecting great credit upon himself and upholding the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Tradition Continues

On July 4, 2025, a devastating flood occurred in the hill country of Texas. A stalled rainstorm in the area caused the Guadalupe River to crest at 37 feet. That wall of water swept away campers and campgrounds in this favorite holiday and summer vacation area. Over 135 deaths occurred as a result of the over 30-foot wall of water rushing down the flat river canyon in the dark of the night. USCG was again called out to rescue the stranded and recover the deceased. A USCG rescue swimmer, Scott Ruskan (26) of New Jersey, stationed in Texas, was one of those deployed. He is credited with saving 165 flood victims. He was quickly called out as an American Hero by Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem for his actions, but he was just one of many rescuers who answered the call.

The USCG and USN responded to Hurricane Katrina flooding, and will in the future, with skill and poise. These men and women were tested for days. Thousands of lives were saved. They demonstrated the best of our military aviators.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED