Charles Kettles

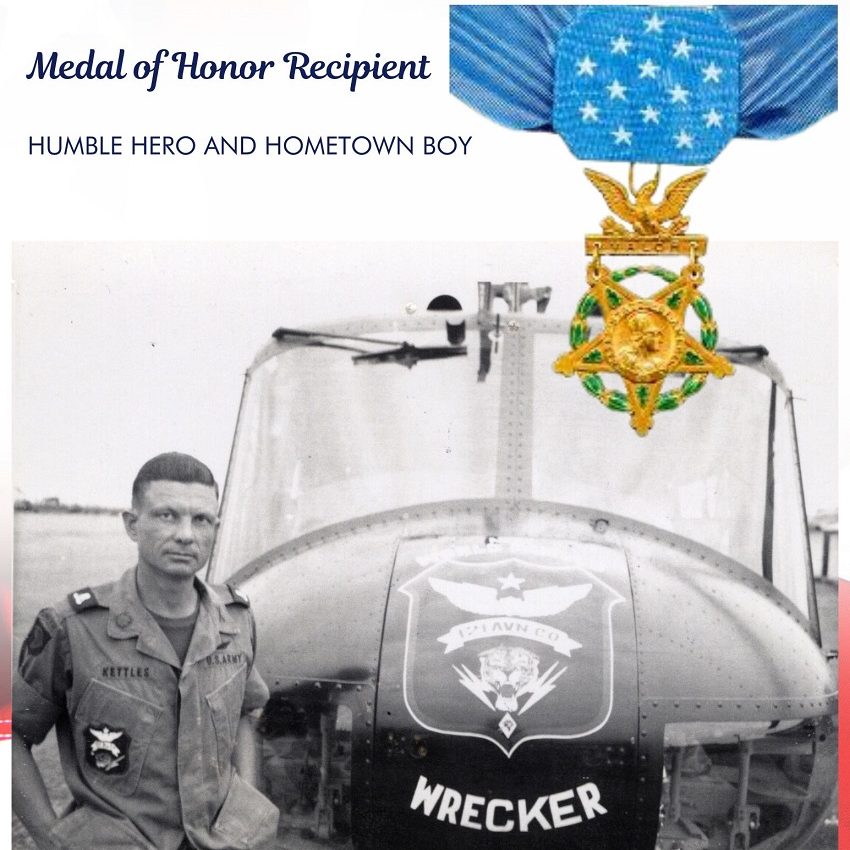

Medal of Honor Recipient

By James G. Fausone, Esq.

Charles Kettles had flight in his DNA and remained a hometown boy his entire life. Lt. Colonel Kettles came from simple beginnings and remained humble his entire life. He was born in Ypsilanti, Michigan, on January 9, 1930. His father, Albert Grant Kettles, was an airplane pilot, and his mother, also a pilot, was Cora Leah Stoble Kettles. He was the third of five sons. He attended Edison Institute High School in Dearborn, Michigan, where he developed his love of flying using the school's flight simulator. After high school, in 1949, he enrolled in Michigan State Normal College (now Eastern Michigan University) in Ypsilanti, where he studied engineering. While a student, he learned to fly. TO pay for his tuition, he worked nights as a baggage handler for American Airlines at Willow Run Airport.

Kettles was living in the shadows of military aviation history, which oozed into his being. Ypsilanti, Willow Run, and Dearborn played a significant role in World War II. Willow Run Airport played a particularly pivotal role in American history, specifically during the 1940s and 50s. The Detroit area in which Kettles grew up was known as the "Arsenal of Democracy". The Willow Run Airport's origins are deeply intertwined with World War II. In 1941, Henry Ford, with the U.S. government's backing, constructed the massive Willow Run Bomber Plant, designed by Albert Kahn. This colossal factory, considered the largest under one roof globally, was built for the mass production of the B-24 "Liberator" heavy bomber.

Ford Motor Company aimed to apply its automotive assembly line principles to aircraft production. At its peak in 1944, the plant was producing a B-24 every 63 minutes, becoming a symbol of America's industrial might. Almost 8,700 B-24s were built there during the war. The plant employed over 42,000 people, a significant portion of whom were women. This influx of female workers, many taking on roles traditionally held by men, contributed to the iconic "Rosie the Riveter" image.

After the war ended in 1945, Ford Motor declined to purchase the plant. The facility was then used by the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation to produce automobiles. The airfield itself transitioned to civilian use. In 1947, the federal government sold Willow Run Airport to the University of Michigan for a symbolic $1.00. In the immediate post-war years, Willow Run became Detroit's principal airport, with commercial airline traffic transferring from Detroit City Airport. It even boasted innovations like the first airport car rental company (Avis, established in 1946) and a movie theater in its luxury passenger terminal. As the decade progressed, commercial air traffic gradually began shifting from Willow Run to the newly enlarged Detroit Metropolitan Airport, which was closer to Detroit. This ultimately led to the decline of Willow Run as a major passenger hub, though it continued to serve as a cargo and general aviation airport.

Army Service (1941)

Two years into his college education, Kettles was drafted into the Army in 1951 as the Korean War escalated. When asked about being drafted, Kettles said, "I think we all have an obligation in this country to respond where need may be... It's your country. It's up to you to protect it."

Courtesy: WikiMedia

Kettles attended Officer Candidate School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and earned his commission as an armor officer in the U.S. Army Reserve on February 28, 1953. The Korean armistice was signed in July 1953. He got a training slot for pilot school and graduated from the Army Aviation School in 1954. Following his training, Kettles served active-duty tours in South Korea, Japan, and Thailand. On the horizon was American involvement in the Vietnam conflict, which started in 1955.

He was released from active duty in 1956. Kettles returned home and established a Ford Dealership in Dewitt, Michigan, with his older brother, Richard. The Kettles Ford Sales, Inc., in Dewitt was an hour or so drive from his Ypsilanti home. Kettles also continued his service with the Army Reserve as a member of the 4th Battalion, 20th Field Artillery.

Kettles answered the call to serve again in 1963, when the United States was engaged in the Vietnam War and needed pilots. Fixed-win-qualified, Kettles volunteered for active duty, but the need was for rotor heads. Kettles attended Helicopter Transition Training at Fort Wolters, Texas, in 1964. During a tour in Frances the following year, Kettles was cross-trained to fly the famed UH-1D "Huey".

Kettles reported to Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1966 to join a new helicopter unit. He was assigned as a flight commander to the 176th Assault Helicopter Company, 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, and deployed to Vietnam from February to November 1967.

The UH-1D "Huey" helicopter was a Vietnam workhorse and provided the soundtrack for that conflict. It was used in various roles (troop transport, gunships, medical evacuation). The war planners recognized that this jungle war, with few roads and many mountains, was ideal for the use of helicopters for logistics, medical evac and assault. The Huey helicopter allowed the Army to own the airspace.

Courtsey: Army.Mil

Medal of Honor Actions

His notable actions in Vietnam occurred on May 15, 1967. As a flight commander with the 176th Aviation Company, then-Major Kettles volunteered to lead a flight of six UH-1D helicopters to bring reinforcements and evacuate wounded personnel for an airborne infantry unit engaged in an intense firefight near Duc Pho. Despite heavy enemy fire, he refused to depart until all reinforcements and supplies were offloaded and wounded personnel were loaded. He then led the flight back to the staging area.

As Kettles explained to VeteransRadio.org host and fellow Vietnam helicopter pilot Dale Throneberry:

KETTLES: It was a mission that lasted most of one day. It involved inserting a total of 160 troops into an LZ. During the course of the day, they had walked into an ambush, and it took its toll. At the end of the day, that is about 1900, or 7 p.m., the battalion commander requested emergency extraction of the remaining 40 troops, plus four of my crew members from a helicopter that had taken a mortar round on the mast of the helicopter and was destroyed in place. They, of course, immediately ended up being infantry troops. So there was a total of 44 troops. The unit from which I came was reduced to where we only had one remaining UH-1D helicopter flyable to make the extraction. So we borrowed five from the 161st, which was about 30 miles up the road, and rendezvoused in the area of the LZ landing zone and went in in a trail formation. And shortly after we landed, the troops, of course, loaded, and the aft helicopter crew members advised that everyone was loaded. So I gave a thumbs-up to the co-pilot to take us out, and I did a 180 in the air coming back toward the base. I was advised that there were still eight troops down in that landing zone in the riverbed who had been putting up a last-ditch defense, protecting those who were boarding but didn't get on the helicopter themselves.

So they were down there against a battalion-sized North Vietnamese Army battalion, and it was a bad scene. Anyway, I told the commander that I would, of course, go right down and pick them up. I had picked up only one ground troop. They went to the nearest helicopter and got on board. And so I was in the left seat, and the troops were to my left. So I took control and headed into the valley to pick up the eight. And immediately on touchdown, or a few seconds later, a mortar round went off the nose of the helicopter, which took out part of the windshields left and right, the chin bubble where I sat. And, of course, the troops loaded up pretty fast. As one stated in Washington before the ceremony for the MOH, when interviewed by the press, he said, "Well, after I landed, he started running toward the helicopter. And he said the tracers were going past his head. But he said, and then he really began running, and he was staying ahead of the tracers. So he must have had a hell of a pace."

As I learned later, the helicopter, when the co-pilot picked it up, fishtailed out rather violently and threw one of the grunts out the left door. He grabbed the skid on the way out, and his compatriots pulled him back in. But then a mortar round went off beneath the tailbone, and a rather dramatic departure. But the helicopter was over gross weight by probably 600, 700 pounds, and it flew like that, too. About like a two-and-a-half-ton truck with a rotor system on it. And to sustain flight, it couldn't because it was too heavy. And so I did a combination of a running landing, wherein you simply lower the collective pitch because the engine was not strong enough to maintain rotor RPM normal, and there's no point in continuing to pull because it's just going to settle further. And after a jackrabbit departure down the riverbed, allowing the helicopter to come back down on the nose of the skid to regain the rotor RPM so I could fly it again, treating that RPM for forward speed to get about 40 knots. And after about five or six of those jackrabbit attempts— bouncing down this little riverbed. Anyway, I wasn't sure whether I was going to get up and go or if 13 of us were going to be down there with Charlie. But fortunately, it departed like a good fellow and went back to base.

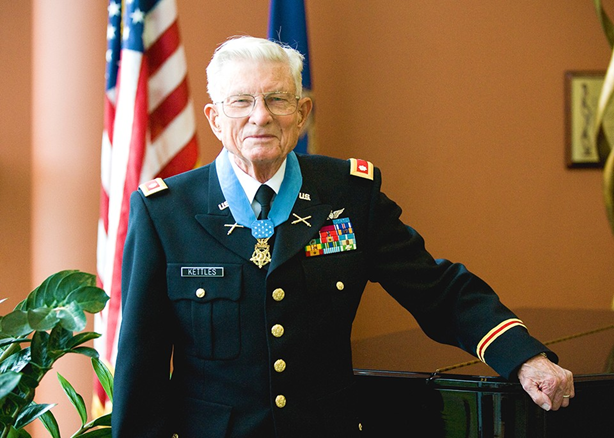

The Nation's highest honor was bestowed some 50 years after Kettle's actions as flight commander of the 176th Assault Helicopter Company. President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Honor to Kettles on July 18, 2016, in a ceremony at the White House.

Lt. Col. Charles Kettles' Medal of Honor citation reads as follows:

Major Charles S. Kettles distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while serving as Flight Commander, 176th Aviation Company (Airmobile) (Light}, 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, Americal Division near Duc Pho, Republic of Vietnam. On 15 May 1967, Major Kettles, upon learning that an airborne infantry unit had suffered casualties during an intense firefight with the enemy, immediately volunteered to lead a flight of six UH-1D helicopters to carry reinforcements to the embattled force and to evacuate wounded personnel. Enemy small arms, automatic weapons, and mortar fire raked the landing zone, inflicting heavy damage to the helicopters; however, Major Kettles refused to depart until all helicopters were loaded to capacity. He then returned to the battlefield, with full knowledge of the intense enemy fire awaiting his arrival, to bring more reinforcements, landing in the midst of enemy mortar and automatic weapons fire that seriously wounded his gunner and severely damaged his aircraft. Upon departing, Major Kettles was advised by another helicopter crew that he had fuel streaming out of his aircraft. Despite the risk posed by the leaking fuel, he nursed the damaged aircraft back to base. Later that day, the Infantry Battalion Commander requested immediate, emergency extraction of the remaining 40 troops, including four members of Major Kettles' unit who were stranded when their helicopter was destroyed by enemy fire. With only one flyable UH-1 helicopter remaining, Major Kettles volunteered to return to the deadly landing zone for a third time, leading a flight of six evacuation helicopters, five of which were from the 161st Aviation Company. During the extraction, Major Kettles was informed by the last helicopter that all personnel were onboard and departed the landing zone accordingly. Army gunships supporting the evacuation also departed the area. Once airborne, Major Kettles was advised that eight troops had been unable to reach the evacuation helicopters due to the intense enemy fire. With complete disregard for his own safety, Major Kettles passed the lead to another helicopter and returned to the landing zone to rescue the remaining troops. Without gunship, artillery, or tactical aircraft support, the enemy concentrated all firepower on his lone aircraft, which was immediately damaged by a mortar round that shattered both front windshields and the chin bubble and was further raked by small arms and machine gun fire. Despite the intense enemy fire, Major Kettles maintained control of the aircraft and situation, allowing time for the remaining eight soldiers to board the aircraft. In spite of the severe damage to his helicopter, Major Kettles once more skillfully guided his heavily damaged aircraft to safety. Without his courageous actions and superior flying skills, the last group of soldiers and his crew would never have made it off the battlefield. Major Kettles' selfless acts of repeated valor and determination are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Army.

Courtesy: Library of Congress

President Obama cited Kettles' actions as the ultimate example of the U.S. Military motto, never to leave a comrade behind, and also noted Kettles' humility in dismissing what he termed the "huh-huh" regarding his actions 50 years ago.

"You couldn't make this up... It's like a bad Rambo movie," Obama said, marveling at the narrative of Kettles' repeated selflessness and bravery in the face of withering fire in what was known as "The Valley of Chumps" for the danger it posed to American soldiers.

"In a lot of ways, Chuck is America," Obama said. "To the dozens of American soldiers that he saved in Vietnam half a century ago, Chuck is the reason that they lived and came home and had children and grandchildren. Entire family trees - made possible by the actions of this one man."

Obama noted that a soldier who was there that day said Kettles became their John Wayne. President Obama said, "With all due respect to John Wayne - he couldn't do what Chuck Kettles did."

Post-Vietnam War

In 1970, as the war was being lost and wound down, Lt. Col. Kettles went to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, where he served as an aviation team chief and readiness coordinator supporting the Army Reserve. At the same time, Kettles attended Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, where he received his bachelor's degree. Kettles retired from the Army in 1978 and had been awarded the Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, two Bronze Star Medals, 27 Air Medals, and two Army Commendation Medals.

How was his story forgotten for so long? Well, Kettles, like most Medal of Honor recipients, did not talk or brag about his exploits. In fact, it became uncovered again when fellow vet Bill Vollano was working on a Veterans History Project for the Ypsilanti Rotary Club in about 2020. He interviewed Kettles and felt that Kettles should have been awarded the Medal of Honor back in Vietnam. Kettles felt he was just doing his job. He simply explained on Veterans Radio that he kept going back for the men because you could not leave a man behind. His reward was, "That the mission, as far as I was concerned, was finished and satisfactory. Those 44 names don't appear on the wall in Washington. In the south, that was gratification enough." He did not concern himself with medals and awards. Vollano and team developed more of the story and obtained statements to submit an upgrade package to the Army.

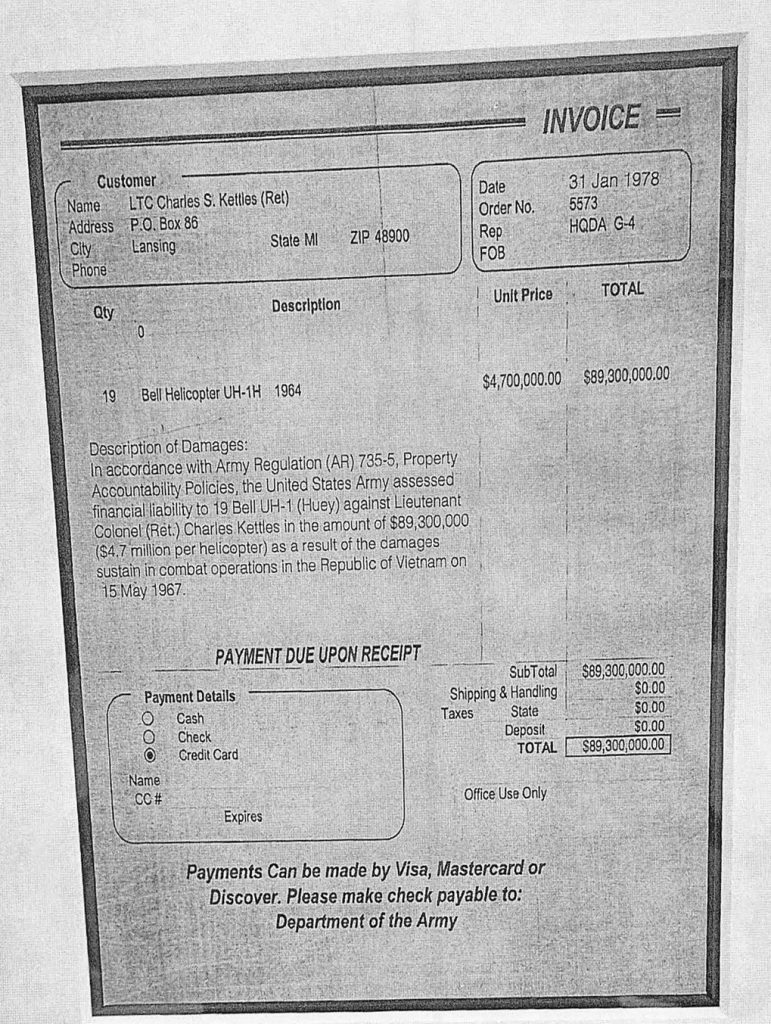

War is serious and brutal. However, you can find humor in the circumstances. In January 1978, the Department of the Army sent Kettles an invoice for 19 Hueys that were shot up while he was flying them in Vietnam. The bill was for $89,300,000. He forwarded a letter explaining what happened to those helicopters. One was a total loss, but "the other 18 helicopters required various responsibilities for leading each of the five flights in and out of the LZ and the single aircraft back in to pick up the last eight infantry soldiers. IN view of the above information, some offset ot the $89,300,000 would seem appropriate." This joking continued, and in November 2016, the Secretary of the Army waived the financial liability for damaging those 19 Hueys if Kettles acted "as an ambassador for the Army to help tell our story to the men and women both in and out of uniform."

The invoice, response, and waiver are on display at the Charles S. Kettles VA Medical Center - Ann Arbor, which was renamed in honor of Charles Kettles in 2020.

After returning to Michigan, Kettles earned his master's degree in commercial construction from Eastern Michigan's College of Technology. Kettles taught students at Eastern while simultaneously developing the Aviation Management program. Kettles served as professor of the Program he developed at Eastern Michigan University. He was active in the local Kiwanis, as well as the Capt. C. Robert Arvin Educational Fund of the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 2408. He was well known at the Vietnam Veterans of America Post 310 in Ann Arbor.

Courtesy: Eastern Michigan University

Kettles' first wife was Anna Theresa Maida of Philadelphia. They married on August 25, 1956, and had six children. They divorced on September 21, 1976. He later married his second wife, Catherine ("Ann") Cleary Heck, on March 14, 1977. Their marriage continued for 42 years until he died in 2019.

Because of his courageous actions in war as well as his deep connections with Eastern Michigan University, the Military and Veterans Services Resource Center was renamed after Kettles in 2016. Kettles was also presented with an honorary Doctor of Public Service degree by Eastern Michigan University at his home in 2016. His character serves as an empowering and inspiring example for both the military and students of Eastern Michigan University.

Kettles' involvement in the community and his character were known throughout the community. In 2021, the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Ann Arbor was renamed in honor of the late Lt. Col. Charles S. Kettles, a lifelong Ypsilanti resident. He died on January 21, 2019, at the age of 89. Later that year, he was inducted into the Michigan Military & Veterans Hall of Honor.