Arthur W. Wermuth

"One Man Army"

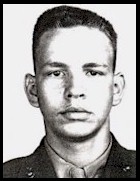

Arthur Wermuth didn't look like a U.S. Army officer. Sporting a mustache and Vandyke beard, the former football star from South Dakota endured his baptism of combat in the last week of 1941 and into the first week of 1942. Departing Manila on the day after Christmas with the 150 men of Company D, 57th Infantry (Philippine Scouts), he had been ordered by Colonel George Clark to put his small force in the lines on Northern Luzon and "Dig in and hold!.

Arthur Wermuth didn't look like a U.S. Army officer. Sporting a mustache and Vandyke beard, the former football star from South Dakota endured his baptism of combat in the last week of 1941 and into the first week of 1942. Departing Manila on the day after Christmas with the 150 men of Company D, 57th Infantry (Philippine Scouts), he had been ordered by Colonel George Clark to put his small force in the lines on Northern Luzon and "Dig in and hold!.

Facing Wermuth's small and generally untrained but equally determined force of Philippine Scouts was an entire division of Japanese, rapidly pressing south after landing on the northern coast of Luzon. After ten days of resistance, Captain Wermuth no longer had a force to command--only 37 of his soldiers had survived. They, along with other units of General Jonathan Wainwright's Northern Luzon force had been finally forced to fall back.

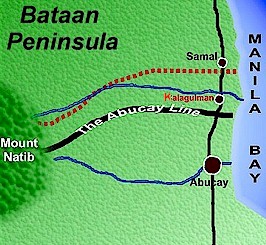

Meanwhile, General Wainwright aligned his forces south of the Calaguiman River which flowed from nearly-mile-high Mount Natib which splits the Bataan Peninsula, eastward into Manila Bay. The river was a defining geographical feature in what became known as the Abucay Line, a final defensive position in efforts to hold out against Japanese General Homma's advance down the east side of Bataan until promised reinforcements arrived. Straddling the river was the important junction barrio of Kalaguiman.

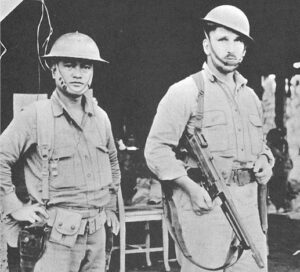

On January 9, when the Japanese launched the first in a long series of ferocious attacks against the Abucay Line, Company A of the 57th Infantry (Philippine Scouts) held positions near Kalaguiman, which was north of the Abucay Line and the main force of defenders. The Filipino soldiers and their American officers were battle-weary and demoralized in the face of continuing, and seemingly futile resistance. To bolster morale, Captain Wermuth, whose Company D had been nearly annihilated, was sent to join them. Three days earlier Wermuth had demonstrated his uncanny combat abilities by proceeding alone past thousands of Japanese troops to reach an outpost isolated behind enemy lines. It had been the beginning of an incredible series of actions that would make the imposing figure of a man, who went into combat with a Thompson sub-machine gun slung over his shoulder and two .45 caliber pistols holstered like a western gunfighter, one of the first American heroes of World War II.

By the following night, the continuing onslaught had forced the Philippine Scouts further south and the Japanese had entered and controlled Kalaguiman. At Allied headquarters, it was determined that the only effective way to delay further advance was to destroy the barrio and then blow the wooden bridge across which enemy troops continued their advance south. Captain Wermuth volunteered to do the job.

Setting out before dawn, and toting two five-gallon drums of gasoline, Wermuth slipped past infiltrated enemy snipers, deep behind what was now the enemy line, and into Kalaguiman. With the wind blowing from the north, he crept all the way through the town, now inhabited by hundreds of Japanese soldiers, most of them still quietly sleeping in the huts of local villagers that their invasion had displaced to the surrounding jungles. Behind him, back behind the friendly lines, Filipino artillerymen were preparing their big guns for a major fire mission. The plan, worked out earlier that morning, was to begin shelling the city five minutes after the first wisps of smoke from Wermuth's fire were seen. The delay was all the time that would be allotted Wermuth to blow the bridge with a satchel charge of TNT he also carried, and effect his escape.

Setting out before dawn, and toting two five-gallon drums of gasoline, Wermuth slipped past infiltrated enemy snipers, deep behind what was now the enemy line, and into Kalaguiman. With the wind blowing from the north, he crept all the way through the town, now inhabited by hundreds of Japanese soldiers, most of them still quietly sleeping in the huts of local villagers that their invasion had displaced to the surrounding jungles. Behind him, back behind the friendly lines, Filipino artillerymen were preparing their big guns for a major fire mission. The plan, worked out earlier that morning, was to begin shelling the city five minutes after the first wisps of smoke from Wermuth's fire were seen. The delay was all the time that would be allotted Wermuth to blow the bridge with a satchel charge of TNT he also carried, and effect his escape.

Creeping quietly all the way through the city, Wermuth reached the northern limits and then retraced his steps, spreading his gasoline against the walls of thatched-roof hamlets, inside which many enemies still slept despite the fact that it was nearly 10 a.m. The dangerous task at last done, he struck a match and began to head for the all-important bridge. The ensuing fire alerted the entire enemy force, many of whom streamed into the hard-packed dirt main street aflame and dying. Others began quickly to search for the intruder. Creeping through a dark alley, Wermuth found his way blocked by three enemy soldiers. So far the shadows had masked his presence but he knew time was running out. He also realized also that any attempt to shoot them down would expose his location and subject him to immediate and merciless gunfire. He glanced nervously at his watch as precious seconds ticked away. With four minutes left he started to raise his Thompson when the three Japanese finally moved away. Creeping quickly through the alley, he finally broke into the bright sunshine and began a desperate zigzag race towards the bridge.

Bullets began to spray all around him, one of them drilling into Wermuth's leg and forcing him to stumble briefly. Ignoring the pain he raced on, even as the first rounds of what might now be not-so-friendly artillery began to rain down on Kalaguiman. Fortunately, the firepower did distract the enemy enough to give Wermuth the time he needed to plant his charges, blow the bridge, and then carefully crawl his way back through the hidden Japanese snipers to reach friendly lines. There, doctors removed a small-caliber bullet that had lodged in his calf, barely missing bone, and Captain Wermuth earned his first Purple Heart.

For Captain Arthur Wermuth, it had been a risky but necessary venture. Behind him, beyond the burning ruins of the bridge and inside the smoldering ashes of Kalaguiman, lay the blackened bodies of more than 300 Japanese soldiers.

Heroes of Bataan

The fighting along the Abucay Line that second week of January was fierce, brutal, and critical to the efforts to hold. Captain Arthur Wermuth's heroic actions in destroying the bridge at Kalaguiman only temporarily delayed the Japanese advance on the Allied main line of resistance. On the night and following day of January 11-12, not far distant from Kalaguiman, Second Lieutenant Arthur Sandy Nininger found himself confronted by hordes of advancing enemy soldiers. Though assigned to Company A, 57th Infantry, during the brief respite from combat Wermuth's action had provided, Nininger had attached himself to Company K in efforts to recapture positions along the line, taken when the Japanese infiltrated a cane field.

The fighting along the Abucay Line that second week of January was fierce, brutal, and critical to the efforts to hold. Captain Arthur Wermuth's heroic actions in destroying the bridge at Kalaguiman only temporarily delayed the Japanese advance on the Allied main line of resistance. On the night and following day of January 11-12, not far distant from Kalaguiman, Second Lieutenant Arthur Sandy Nininger found himself confronted by hordes of advancing enemy soldiers. Though assigned to Company A, 57th Infantry, during the brief respite from combat Wermuth's action had provided, Nininger had attached himself to Company K in efforts to recapture positions along the line, taken when the Japanese infiltrated a cane field.

On the night of January 11, following an artillery barrage, hoards of Japanese had attacked the line in a Banzai charge. Waves of screaming enemy soldiers streamed into the lines in the face of intense fire, men of the leading wave throwing their bodies over barbed-wire barricades to create "bridges" over which the following waves could pass. Narcisco Salbadin manned a water-cooled machine gun in an effort to beat back the enemy. He killed dozens of attackers but each time one fell, it seemed two more rushed forward to replace him. When his machine gun jammed, Salbadin began firing with his .45 pistol, killing five. His thumb was severed when one Japanese soldier attacked him with a bayonet, but despite the loss, he maintained his grip, wrested the rifle from the attacker, and then reversed it to ram the bayonet into the enemy soldier's chest.

As the Banzai charge, at last, began to falter, the Scouts turned offensive to throw back the enemy and regained ground now claimed by the Japanese. Lieutenant Nininger's subsequent Medal of Honor citation reveals his own uncommon heroism: "In the hand-to-hand fighting which followed, Second Lieutenant Nininger repeatedly forced his way to and into the hostile position. Though exposed to heavy enemy fire, he continued to attack with rifle and hand grenades and succeeded in destroying several enemy groups in foxholes, and enemy snipers. Although wounded three times, he continued his attacks until he was killed after pushing alone far within the enemy position." In that action, Second Lieutenant Nininger became the first member of the U.S. Army to earn the Medal of Honor in World War II. Ultimately, the Japanese advance had been temporarily halted, but the charge had left hundreds of Japanese snipers alive, and hidden in trees and trenches all along the Abucay line. The task of finding, and destroying them was going to take days of deadly fighting.

For Arthur Wermuth, the continuing attacks mean no time to recover from his own wounds. Five U.S. Marines, displaced from their own unit during the battle for Bataan, arrived at the 57th Infantry Headquarters. Sergeant Bill Eckstein described his men as on "detached service with the U.S. Army to teach them how to fight." Eckstein and his comrades were quickly welcomed by Wermuth, who wasted little time putting them into action.

On January 15, Captain Wermuth deployed what was left of his company along the cane field that bordered the left side of the main road between Kalaguiman and Abucay. He then dispatched two patrols to begin burning the field, leading one patrol himself and placing the other patrol under the charge of Marine Sergeant Eckstein.

Eckstein's patrol reached the center of the field first, an elevated clearing, and the displaced Marine raised up to peer beyond. Suddenly five rounds slammed into his body, severely wounding him. Marine privates Bill Brown and Al Sheldon crawled forward to their sergeant, amid a continuing hail of enemy fire. "Get out of here with the Sarge," Brown shouted, even as scores of Japanese raced, firing as they ran, at his exposed position in the clearing. While Sheldon dragged his sergeant to safety, Brown knelt and coolly snapped off deadly single-shots for five minutes, dropping Jap after Jap. Then his luck began to run out. More than 100 Japanese raced to the edge of the clearing, setting up a machine gun to rake Brown's position. Repeatedly hit by enemy fire, Brown maintained his position, holding an entire Japanese company at bay until his sergeant had been removed to safety.

For extraordinary heroism in action in the vicinity of Abucay, Bataan, Philippine Islands, on 15 January 1942. While on legal leave from his proper unit, Private First Class Brown voluntarily joined a detail from the 57th Infantry which was charged with the mission of destroying an enemy position through which snipers were infiltrating into our lines. During the performance of this mission this intrepid soldier, observing that one of his companions had been severely wounded, and was unable to move, proceeded without orders in the face of enemy machine-gun fire at close range in an effort to evacuate the casualty. Silencing a hostile gun by a well-placed hand grenade, and inflicting several additional casualties on another enemy group which prevented his reaching the vicinity of the wounded man, Private First Class Brown had thereby disclosed his position to the enemy and was mortally wounded by the ensuing enemy fire.

For Captain Arthur Wermuth, watching that young Marine's valiant stand was at once both inspiring and heart-rending. Even when Private Brown was dead, the Japanese continued to vent their hatred by raking his body with machine-gun fire. Yelling above the fray, Wermuth shouted, "Jock, burn the field," and then to his men, "Shoot every little son-of-a-bitch who comes running out." By sunset, 207 dead Japanese lays in and around the cane field.

"Jock" was Sergeant Crispin Jacob, Captain Wermuth's closest friend. Described by Wermuth as "a huge black native from Zamboanga (a southern Philippine Island)," the half-Filipino/half-oriental giant would join his commander in exploits that would become legendary.

General Douglas MacArthur awarded Captain Wermuth the Distinguished Service for his actions in and around Kalaguiman during the week of 10 to 16 January 1942. On February 23, 1942, TIME magazine detailed Wermuth's exploits under the headline "One Man Blitz", describing one of Wermuth's missions:

"On one of his reconnaissance patrols Captain Wermuth, from a foxhole, spotted a long line of Japanese crossing a ridge. 'I worked them over with my Tommy gun,' he said, 'and got at least 30 like ducks in a Coney Island shooting gallery.' Attracted by the shooting, five Filipino Scouts rushed to the scene, helped Arthur Wermuth polish off '50 or 60' more of the enemy party."

By the time that story gave the American public one of its first LIVING heroes of the war, throughout the Philippines Captain Arthur Wermuth had become known as the One Man Army of Bataan. Among the Japanese, who now had placed a reward, dead or alive, on Arthur Wermuth or his band of 84 volunteer snipers, Wermuth was known by another nickname--Bataan ne Yurei....

The Ghost of Bataan

When the stories of Captain Arthur Wermuth began circulating back in the United States, they contained the information that the One Man Army of Bataan has "Absolutely accounted for at least 116 Japanese dead and an inestimable number of prisoners." Hearing this, Colonel Royal Page Davidson, Superintendent of Northwestern Military and Naval Academy at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, told Time magazine, "Is that all? He'll have to do better than that!" No doubt it was a comment made with both pride and expectation. Colonel Davidson knew Wermuth well as a young man, and Wermuth would in fact do better than that before he was done.

The son of a World War I veteran and prominent Chicago family that subsequently moved to a ranch in South Dakota, Arthur Wermuth grew up in that tough Old West fashion. During summers he worked the ranch, and the rest of the year attended classes at Northwestern, where he excelled at football, in at nothing else. In fact, Wermuth's poor grades and, perhaps, even more, his rough lifestyle, preempted his initial goal of attending West Point. Wermuth once told a friend that it was because of his "old-fashioned Dutch temper" and "because of these mitts (that) has gotten me into plenty of trouble" that he was forced to settle for an ROTC commission while attending classes at North Park University.

In 1940 Wermuth wrote to the War Department to request active duty and arrived in the Philippines in January 1941 to assist in training the Philippine Scouts. After Pearl Harbor was attacked he was quickly promoted to Captain. Thus began a month-long campaign that turned the former football star into the subject of one of the few stories in the first few months of World War II to spark the hopes of our nation. The public loved the legend, for all of America was desperate for any good news from the war zone and hungered for epochal heroes. Wermuth provided both, but it also made him one of Japan's most hated, and singled-out enemies.

Wermuth's actions on the Abucay line were just a beginning of a campaign that saw him develop and train a team of snipers that, turning guerrilla, began to wage war on the Japanese with the same jungle tactics they had honed themselves. Author Lowell Thomas noted in 1943, in one of the first books written about the heroes of World War II:

"His fame during the Bataan fighting was featured by his exploits behind the enemy lines, that being his favorite theater of action: deep in the rear of the enemy positions, where an American soldier would be least expected and where the Jap hunting would be the best. Wermuth had a weird knack of getting through, an uncanny skill typical of the tactics of guerilla warfare, skill in passing through enemy forces, creeping and shooting his way through when necessary. He had a genius for concealment and cover, and besides, he was thoroughly familiar with the terrain."

On one of Wermuth's solo missions deep behind enemy lines, while hidden in dense jungle, a Japanese patrol passed by with one member nearly stepping on him. Wermuth noted the patrol was headed towards the Allied lines--and his comrades and quickly stood in the darkness to join the enemy column. Hunching low, he followed along for miles in the dark jungle, even "Shushhhhing" the Japanese soldier ahead of him when the man stumbled and created too much noise. When the patrol neared the fortified positions of the Philippine Scouts, fearing he might be taken under fire by his own comrades, Wermuth intentionally stumbled into the soldier ahead of him, handing off a live grenade before quickly melting back into the jungle. One enemy soldier died in the subsequent blast, the remainder died when their position was thus exposed to the Scouts who promptly opened fire. These, and countless missions like it, are what earned Wermuth the Japanese title, Ghost of Bataan.

More often than not, however, Wermuth's solo missions were at the least carried out with his comrade, Jock. Every time the intrepid Captain headed behind the lines, Jock would plead his case and ultimately get permission to participate. In all too many cases, it was a fortunate decision by Wermuth, for, again and again, Jock's innate jungle proved invaluable. Also, more than once, the Filipino giant who stood 6'4" and weighed in at 220, saved his Captain's life. Such was the case in what might well have been Wermuth's most famous escapade.

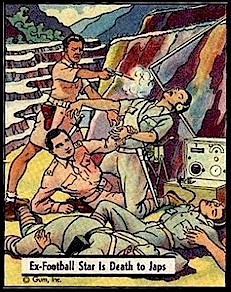

During the efforts to hold the line on Bataan, at one point it became obvious that the Japanese had located and tapped into the wires that provided communications between Allied units. Again when volunteers were needed, Jock and Wermuth set out to find the source of the deadly problem that provided the enemy with intimate knowledge of Allied strength, positions, and movement.

Daringly once again penetrating enemy-held jungle and muddy paddies, the two men searched in vain for the wiretap. Returning in disappointment to their own lines, Captain Wermuth found the tap by accident. While moving down an overgrown trail a hidden wire caught Wermuth's foot, tripping him and causing him to fall into an equally camouflaged ditch. He landed directly in the lap of an equally surprised Japanese soldier who was monitoring Allied transmissions through headphones.

Scrambling backward as quickly as he could, Wermuth drew his revolver in a fashion reminiscent of the gunfights of the old west, even as the Japanese soldier reached for his own. Wermuth won the draw and, his aim true, quickly killed his opponent.

The immediate threat dealt with, Wermuth was so fascinated by the Japanese equipment in the hidden position, he never saw the two other Japanese soldiers that crept up on him until they were almost ready to pounce on him. This time Wermuth's draw was too slow, and a Japanese bayonet pierced his arm, chipping bone and pinning him to the wall of the ditch. "Jock," he yelled, "Japanese...two more down here."

The immediate threat dealt with, Wermuth was so fascinated by the Japanese equipment in the hidden position, he never saw the two other Japanese soldiers that crept up on him until they were almost ready to pounce on him. This time Wermuth's draw was too slow, and a Japanese bayonet pierced his arm, chipping bone and pinning him to the wall of the ditch. "Jock," he yelled, "Japanese...two more down here."

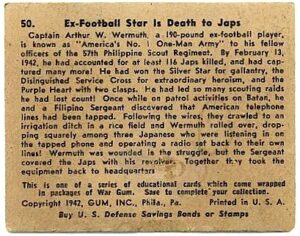

Crispin raced to his commander's aid but, finding the two Japanese soldiers in a virtual hand-to-hand struggle with Wermuth, hesitated to pull the trigger for fear of hitting his comrade. So Jock used the strength of his uncommon size to bludgeon one enemy with the butt of his rifle, then turned and shot the other. Wermuth was nearly passed out from the excruciating pain in his arm, but Jock removed the bayonet, freed the captain, and then carried him safely back to his own lines for treatment--and another Purple Heart. The problem of the enemy-tapped lines was solved, and shortly thereafter one of the cards that came packaged with war gum of the period immortalized that brief skirmish by Jock and Wermuth in a camouflaged ditch behind enemy lines.

Reverse of Wermuth Card

Throughout February and March, Captain Wermuth, Jock, and other of Wermuth's highly trained guerilla fighters continued their heroic efforts to stall the enemy's advance. Despite the futility of that valiant campaign, their work put the enemy on edge and certainly slowed the inevitable collapse of the Bataan defense. Estimates were that at least 500 enemies were killed by the small team of snipers, and generally, it was concluded that the estimate was overly conservative.

Late in March Wermuth's snipers were assigned to recapture the vital heights of Mount Pucat. It was a near-suicide mission, and Wermuth called for volunteers. Virtually every member of his command who was still alive stepped forward.

While slowly working their way through the jungle, a hidden enemy soldier rushed Wermuth at the point of his bayonet. Wermuth slammed his huge fists into the Jap's face as the two of them fell to the ground in a life and death struggle. Pain surged through Wermuth's body when the struggling opponent slammed a knee into his groin, but Wermuth drew his own knife and killed his enemy. The patrol moved out again, killing sixty-five more invaders over the 36-hour trek to the mountain. Once the objective was reached, despite a valiant attempt, the attack failed. For more than half of Wermuth's men, it was indeed a suicide mission. This drastic depletion of his forces signaled what would soon be the end of Wermuth's unprecedented success on Bataan.

A few days later near Anayason Point, machine-gun fire from dug-in positions on the other side of a small stream held up the advance. Wermuth led his snipers across the stream, fully exposed to a withering fusillade of enemy bullets. While out in front and in the open, however, Wermuth had just jerked the ring from a grenade with his teeth and lobbed the orb when he was struck in the left breast by an enemy round. The bullet chipped a rib before passed through a long, once again sidelining the One Man Army--this time far more seriously.

Wermuth was carried to an aid station where the bullet was removed, but he languished in pain and was near death for days while hemorrhaging continued. Slowly he did begin to heal, though he was still a week and the hole in his chest was oozing puss ten days later when, against doctors' orders Captain Wermuth strapped his revolvers on his hips, slung his Thompson sub-machine gun over his shoulder, and returned to the field to join his men. What little remained of Wermuth's fighters were holding desperately to a bitterly contested piece of ground on Signal Hill between Mariveles and Bagac. Wermuth, despite his courage and determination, arrived with too little and far too late. He was still too weak to accomplish much, and on April 9 during the retreat down Trail Ten, behind Mount Sumat, the One Man Army of Bataan slipped in the wet grass, tumbled down the jagged mountain, and was rendered unconscious when his head hit a rock.

When Wermuth regained consciousness he found himself at Field Hospital Number 2, now in Japanese hands. The Ghost of Bataan had finally been captured.

Following torturous days in the infamous Bataan Death March, Captain Wermuth was held prisoner of the Japanese, who despite the fact that their most hated enemy was now under their control, feared the One Man Army. Elliott Junior Smelser, a fellow POW recalled in 1993 of his own captivity:

"The first year of my captivity I worked on building an airfield for the Japanese. Life was not bad because they were afraid of the Major in Charge. His name was Major Wermuth and the Japanese called him 'Wermuth the Lion'."

After spending time at Cabanatuan, Lipa, Bilibid, and then back to Cabanatuan, in December 1944, Major Arthur Wermuth joined 1,618 of his fellow prisoners aboard the unmarked Japanese prison ship Oryoku Maru, for a voyage to prison labor camps in Japan. On the night of December 14, American airplanes bombed the Oryoku Maru, little realizing more than 1,500 Allied prisoners were aboard. The Japanese beached the vessel, leaving the prisoners and only a few guards on board despite the fact that all of them knew Allied planes would return soon.

The American planes from the U.S.S. Hornet did indeed return the following morning, and, still unaware that the ship contained Allied prisoners, the pilots unleashed a torrent of bombs that killed 300 POWs. Following the attack, the Japanese guard, at last, allowed the prisoners to abandon ship and swim to shore. Many never made it. Those who did create the pattern of white spots seen on the water in this photograph that was taken from an American airplane from the Hornet shortly after the attack.

Major Wermuth was among the survivors of the first Hell Ship, swimming ashore at Olongapo. All the prisoners were quickly rounded up by their captors, and transported to San Fernando in boxcars. Two days after Christmas the Brazil Maru and Enoura Maru crammed more than 1,000 prisoners into their small and filthy holds. Brazil's most recent cargo had been horses, and the hold was still soiled with un-removed manure. Wermuth was among those that suffered hell in the belly of Enoura Maru, the hold of which was filled with dust and residue from its recent cargo of coal. On December 31 the two ships reached the Formosan harbor of Takao. The Japanese held up there to celebrate the New Year, leaving the prisoners cramped below with little food or water, and no medical treatment, though nearly all prisoners were sick and many had already died.

The Enoura Maru was still at Takao on January 9, 1945, when aircraft from the U.S.S. Hornet again attacked an unmarked Japanese ship, unaware that the bombs they dropped into the front hold immediately killed one half of the 500 Americans crammed into that space. Nearly every man who wasn't killed, including Major Wermuth, were wounded by flying shrapnel. It was friendly fire that netted Wermuth his fourth Purple Heart.

For three days the Japanese left the bodies of the American dead where they fell, littering a hold still crammed with wounded and bleeding American prisoners. Finally, on January 12, the dead were carried out and the surviving 890 prisoners were transferred to the Brazil Maru for the final leg of their journey to Japan. By the time the prisoners reached Moji, Japan, there were fewer than 500 survivors from among the 1,691 POWs who had boarded the Oryoku Maru less than a month before. Within three months, another 100 prisoners died of disease and/or wounds received on that tragic journey from prison camps in the Philippines to labor camps in Japan. Fewer than 400 survived the war.

Early in 1945, the U.S. Army changed the status of Major Wermuth from Prisoner of War to Killed in Action, believing the man who had become legendary as the One Man Army of Bataan three years earlier was now a casualty of Japanese brutality.

Five days after the Japanese surrendered, an American officer stood before a large group of sick, starving, and often still-wounded but now free prisoners. Slowly the names of soldiers long missing in action, or known to have been prisoners of war, were called out. Occasionally a feeble voice would answer "here!" Far more often, there was no response at all.

"Major Arthur Wermuth," an officer called out loudly, experience having already prepared him only for silence.

"Here!" came a weak voice from among the throng of prisoners. Arthur Wermuth, the Ghost of Bataan, stepped slowly forward.

His 103-pound body was thin, emaciated, and scarred by four combat wounds, as well as the emotional scars that could not

be seen, or understood by more than a few who had, like him endured so much. But Arthur Wermuth was still very alive.

Sources:

Hymoff, Ed, "The Ghost of Bataan", Argosy, December 1961

"One Man Blitz", Time Magazine, February 23, 1942

Smelser, Elliott Junior, "Excerpts from My Autobiography", Spoken at West Point in June 1993

Thomas, Lowell, These Men Shall Never Die, The John C. Winston Company, September 1943

Wermuth, Arthur W., Deposition on Prisoner of War Treatment, October 8, 1945

"Wonderful Lug", Time Magazine, March 16, 1942

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED