Demas Craw & Pierpont Hamilton

Airman On The Ground

Early on the morning of Sunday, November 8, 1942, the airwaves across France and North Africa crackled with a short-wave broadcast. The voice spoke in French with a slight accent, for it was the voice of the American president, Franklin D. Roosevelt. The message was succinct:

"Mes Amis, we come among you to repulse the cruel invaders -- have faith in our words -- help us where you are able. All men who hate tyranny, join with the liberators who at this moment are about to land on your shores.

"Vive La France eternelle."

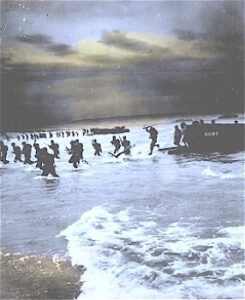

Thirty-thousand American soldiers moved silently across the decks of a vast naval armada in the early morning darkness of that same Sunday morning. There was no moon to reflect off the large cranes that lowered scores of a small landing craft into the heavy swells of the Atlantic from the Western Task Force's position less than five miles off the beaches of French Morocco.

Thirty-thousand American soldiers moved silently across the decks of a vast naval armada in the early morning darkness of that same Sunday morning. There was no moon to reflect off the large cranes that lowered scores of a small landing craft into the heavy swells of the Atlantic from the Western Task Force's position less than five miles off the beaches of French Morocco.

If the young, untried American soldiers were tentative, frightened, and unsure of what fate the dawn might deal them, they'd have found little comfort in the fact that their President and his top commanders shared theirs uncertainly. The mission that was unfolding across a thousand miles of seashore from French Morocco into the Mediterranean was unprecedented. Never before in history had so large an invasion force traveled so far from home to make an amphibious landing on foreign shores. This was to be the first American ground offensive of World War II against Adolph Hitler and the Axis. It was the fulfillment of President Roosevelt's pledge to Winston Churchill eleven months earlier that he would commit ground forces to the European war effort before the end of the year 1942.

The combat uniforms of the invading force were distinctive with The Stars and Stripes are sewn to a sleeve, or emblazoned on an armband, to quickly identify the men as Americans. If the landing force was repulsed and combat ensued, the soldiers from the United States would find themselves fighting to kill a people whose friendship had been enjoyed since the American Revolution.

Twenty-five years earlier American soldiers had sailed from their home shores to reach embattled Paris and proudly proclaim, "Lafayette, we are here." This time the American president wasn't sure if the French would welcome this new American Expeditionary Force as liberators of their colonies in North Africa, or seek to kill them as invaders. In Washington, Roosevelt prayed that his personal radio message to the French people would prompt cooperation and save American lives. But the message's effectiveness could not be known until the first troops stepped upon the sands of French Morocco, or waded ashore further east in Algeria, where the other two elements of the amphibious force were making simultaneous landings.

The nervous young soldiers shouldered their rifles and balanced their heavy packs as they clambered down the cargo nets that had been draped from the sides of their transport. Beneath them in the darkness waiting for the smaller landing craft. The tricky transfer to the shallow barges that would ferry them to shore was made all the more difficult by heavy seas. As the small craft bobbed and pitched, the soldiers crammed together tightly to fill them to capacity.

Near the flagship of Major General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., sat one barge that was empty save for the small crew and one army jeep. Private Orris V. Correy clambered down the net; the driver for the jeep, he would be the only enlisted man debarking from this landing craft. Above him on the deck General Truscott himself was visiting with the other two passengers, giving last-minute instructions, shaking hands, and wishing them well. Then the two Army Air Force officers began their own descent down the net. The only weapons they carried were sidearms, and rather than shouldering backpacks with provisions to sustain them ashore, one man carried only a briefcase.

Near the flagship of Major General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., sat one barge that was empty save for the small crew and one army jeep. Private Orris V. Correy clambered down the net; the driver for the jeep, he would be the only enlisted man debarking from this landing craft. Above him on the deck General Truscott himself was visiting with the other two passengers, giving last-minute instructions, shaking hands, and wishing them well. Then the two Army Air Force officers began their own descent down the net. The only weapons they carried were sidearms, and rather than shouldering backpacks with provisions to sustain them ashore, one man carried only a briefcase.

When the officers reached the platform, the crew revved the engines of the landing craft and turned toward the darkened shoreline in the distance. Ahead in the dim light of dawn could be seen the vague outline of scores of other small barges, each loaded to capacity with young soldiers of the Sixtieth Infantry whose mission was to assault the beach near the resort village of Medhia.

The seas remained turbulent and became increasingly so as the flat barges reached shallow water. Fortunately, the morning was quiet but for the roaring engines of the landing craft. Soon, however, even that noise receded as the barge carrying Private Correy and his jeep turned north, away from the main assault force and towards the brackish water of the Sebou River. While thousands of American soldiers waded ashore at Medhia to fight a war, Private Correy and the two Army Air Force Officers were landing alone on hostile shores for a different purpose. They were on a mission of peace, a mission that hopefully would save hundreds of lives, both American and French.

A Deal with the Devil

It's hard to imagine that just 25 years after American Doughboys were hailed as friends and liberators in Paris in 1918, their sons would return to liberate the French from the same German enemy under the threat of being fired on as invaders. Such was the complicated nature of Axis aggression and expansion in World War II, a scenario brokered by ill-conceived deals with the devil.

Two years after Adolph Hitler ascended to power in Germany he renounced the Treaty of Versailles that had brought armistice in World War I. That treaty restricted the military strength of Germany and hampered industrial efforts to rearm. In 1935, the same year that the German military began rebuilding, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia with an eye to expansion in Africa. The Western democracies (Great Britain, France, and the United States) vigorously protested both acts but were ineffective because the three could not reach a consensus on how to deal with the problem.

Encouraged by the inaction of the Allies, Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland provinces in March 1936. In October, Germany and Italy signed the Axis Pact that allied the two-nation. The following month Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact creating a wide-ranging Berlin-Rome-Tokyo axis of aggression. Both Hitler and Mussolini courted the friendship of the Spanish by sending volunteer troops to aid General Francisco Franco's rightist insurrection against the Spanish Republic. That successful three-year revolution (1936 - 1939) provided combat experience to many German and Italian soldiers. It further endeared General Franco to the Axis and, though Spain remained neutral throughout what became World War II, for Allied planners the Spanish question weighed heavily on every war plan scenario.

"Those who would trade liberty for security shall have and deserve neither."

Benjamin Franklin

In March 1938 German storm troopers entered Austria in order to "restore order" following weeks of unrest actually fermented by Nazi agitators. With the words: "We have yielded to force since we are not prepared even at this terrible hour to shed blood," Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg resigned and was replaced by one of Hitler's Nazi Ministers.

The prospects of war in Europe heightened during the summer when Hitler opened a diplomatic offensive against Czechoslovakia, threatening to invade unless the government allowed the ethnic German population of the Stuetenland on the western border to succeed and be annexed to Germany. Following those tense summer months, representatives of France and Great Britain met with their counterparts from Germany and Italy in Munich. On September 30, 1938, CBS radio correspondent William L. Shirer reported, "It took the Big Four just five hours and 25 minutes here at Munich to dispel the clouds of war and come to an agreement on the partition of Czechoslovakia. There is to be no European war after all."

Early in 1939, in violation of the Munich Agreement and despite his promise that the German appetite for expansion would be sated by the annexation of the Stuetenland, Adolph Hitler took control of the remaining independent portions of Czechoslovakia. He then turned his sights on Poland. Britain and France responded promptly, urging the Poles to resist Hitler's demand to cede portions of the country to Nazi control and promising to aid the people of Poland if they were invaded.

Also, now in desperation, the two western democracies at last also gave serious consideration to previous attempts by the Soviet Union to develop an anti-Nazi military alliance. It was too little too late. Russia was befuddled by the lack of consensus among the western nations and had become convinced they would be ineffective in resisting Hitler. In August 1939 the U.S.S.R. made its own secret deal with the devil, signing a nonaggression pact with Germany. That agreement provided for the partition of Poland by the Reich while allowing the U.S.S.R. a free hand in the Baltic states of Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania.

On September 1 Nazi storm troopers invaded Poland prompting a declaration of war from both Great Britain and France (also Australia and New Zealand) on September 3. Before the month ended Canada too had declared war on Germany. Meanwhile, Poland had been vanquished and partitioned between Germany and the Soviets under their secret agreement of the previous month. In Washington, D.C. President Roosevelt reiterated the American response to the birth of a second worldwide war by saying: "I have seen war and I hate war. I say that again and again. I hope the United States will keep out of this war...and I give you my assurance and reassurance that every effort of your government will be directed to that end."

The President's position echoed the sentiments of his nation. In 1939 while France and Great Britain squared off against the Axis Powers, nine out of ten Americans opposed any American involvement in the struggle for democracy in Europe. Indeed, as difficult as it is to imagine half a century later, among those to favored American involvement in the new World War, a large segment advocated an alliance with the Axis. (One must keep in mind that in 1939 few people of the world knew the depth of Hitler's savagery or racist policy for "ethnic purity". Instead, much of that Axis sympathy was borne out of the heritage of a large American population that had emigrated here from Germany.)

The Phony War (Oct 1939 - Apr 1940)

Following Hitler's successful invasion of Poland, the British and French prepared themselves for a repeat of World War I. Ironically, other than the naval battles of the North Atlantic where German submarines did their best to deny Britain the needed flow of war materials and supplies, the massive world war they feared failed to materialize. It became known as The Phony War, a war without aggression or progress. The media ascribed the title sitzkrieg to the period, as opposed to the blitzkrieg (lightening-swift military offensive) that Germany had employed previously in its rampage across Europe.

The Phony War began with a very real combat action on October 14 when a German U-boat slipped into Scapa Flow off the northeast coast of Scotland to sink the HMS Royal Oak. For the British, for the first time, the war had come dangerously close to home. But as the winter wore on and further combat action failed to materialize, both the British and French were lulled into a false hope that the war in Europe had ended with the partition of Poland. Reality dawned with a shocking blitzkrieg in the Spring.

On April 9 Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in an effort to expand its northern borders. Denmark fell in a 24-hour bloodless occupation; Norway fell within a month. On May 10 Nazi forces simultaneously invaded the neutral Netherlands, Luxemburg, and Belgium, while pushing around the famous Maginot Line to invade France. It was a stunning turn of events.

The Fall of France

Despite the fear of The Phony War period, the French did not believe their homeland was vulnerable to immediate attacks from Germany. The French Army was nearly a million strong with an additional five million trained reserves, and by the spring of 1940, the French had created three armored divisions as well. Most of the nation's 100 infantry divisions were stationed along the eastern borders that separated France from Germany, the same terrain that had seen three years of stalemated trench warfare in the first world war. Between 1930-35 the French constructed the imposing steel and concrete Maginot Line from Switzerland to Luxembourg, to barricade their homeland from a potential German invasion. North of the Maginot line stretched the high mountains and dense woods of the Ardennes Forest, an area believed impassable to tanks.

When Hitler ordered the invasion of France, Generals Heinz Guderian and Erwin Rommel did what the French believed impossible, pouring seven armored divisions into France by way of the Ardennes. On May 12 the enemy crossed the Meuse and the French government was forced to abandon Paris. Defending French and British forces were steadily pushed back towards the English Channel. From May 26 to June 3 the British employed nearly 700 ships to evacuate more than 330,000 beleaguered forces (including 140,000 French Soldiers) from the port at Dunkirk.

One month after the invasion began the Germans finally accomplished what they had failed to do after four years of protracted warfare in the earlier war. On June 14 Nazi soldiers marched triumphantly into Paris. Eight days later the French signed an armistice with Germany to end the hostilities. That left only Great Britain to stand alone against the Nazi onslaught.

After the fall of Paris Hitler focused his attention on Great Britain, attempting from July to October to bomb the island nation into submission during the Battle of Britain. As a matter of self-preservation, Hungary joined the Axis forces in November. Romania allied itself with Hitler in November. Meanwhile, Italy invaded British Somaliland in East Africa in August. In September the 200,000 Italian soldiers that occupied Libya attacked Egypt, which was defended by General Sir Archibald Wavell's 36,000-man Middle East Command. In October Mussolini sent additional troops into Greece. Bolstered by British soldiers, the Greeks held out until Germany invaded the following April. Not until May 1941 did Greece surrender to the Germans. It was a crushing defeat for the British as well.

By the spring of 1941, the Axis controlled all of western Europe except for the valiant and defiant people of Great Britain, neutral Spain and Portugal in the west, Switzerland in central Europe, and neutral Turkey in the east.

By the spring of 1941, the Axis controlled all of western Europe except for the valiant and defiant people of Great Britain, neutral Spain and Portugal in the west, Switzerland in central Europe, and neutral Turkey in the east.

North Africa

Under the strong leadership of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who assumed office in May 1940 and buoyed his nation through the devastating bombardment of the Battle of Britain, England survived the year battered but unbroken. With soldiers, sailors, and airmen from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, Churchill stood virtually alone against the Axis powers for another tenuous year.

Unable to bomb Great Britain into submission, Hitler meanwhile contented himself with the fact that France was occupied by his troops and Paris had fallen. The German dictator looked eastward at the Soviet Union. In the spring of 1941, he invaded Ukraine and on June 22 Nazi tanks began moving on Moscow. On September 8 the blitzkrieg claimed Leningrad. Kyiv fell on October 18. The only major Soviet city left for Hitler to conquer was Moscow, 200 miles away. Only the advent of winter prevented the Soviet capital from falling before the end of 1941. The Soviet's secret deal with the devil in August 1939 had returned to haunt them.

Britain, meanwhile, was concerned with the spreading of Axis control of North Africa and the Mediterranean. Enemy forces occupied Tunisia and Libya and were pushing eastward into Egypt. Axis possession of the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean would allow them to control all shipping through the region and could force Allied convoys from Australia and the Far East to make the long route around the southern horn of Africa.

The British desert offensive began on December 9, 1940, and stretched into two years of combat on the shifting sands of North Africa. By February the Italians had lost 9 divisions, including 130,000 prisoners and 400 tanks. Allied losses were less than 2,000 and it seemed the tide had turned. In response, that same month Adolph Hitler ordered General Erwin Rommel to Tripoli to command his Africa Corps, which landed on February 14.

Despite the early Allied successes, the war for North Africa was far from over.

The Allied forces, which included three Australian Divisions, suffered early defeats at the hands of Erwin Rommel, as well as humiliating defeats in Greece and Crete. Nevertheless, while a handful of Australian Desert Rats became a thorn in Rommel's side at Tobruk, other Allied forces successfully invaded Syria and Lebanon. Throughout the period the United States moved from being neutral to a position of "non-belligerency", rushing needed supplies to both the Soviets and the British under the Lend-Lease Act of 1941. The third beneficiary of that effort "to lend or lease arms to nations those defenses were deemed vital to U.S. security" was China, which was struggling to turn back the tide of Japanese aggression in Asia.

The Japanese themselves had joined the Axis Powers on September 27, 1940, when Germany, Italy, and the Empire of Japan signed the Tripartite (three-party) pact designed to establish a new world order. The concept is quickly apparent in the first three of the agreement's six articles:

Article One:

Japan recognizes and respects the leadership of Germany

and Italy in the establishment of a new order in Europe.

Article Two:

Germany and Italy recognize and respect the leadership of

Japan in the establishment of a new order in greater East Asia.

Article Three:

Germany, Italy, and Japan agree to co-operate in their efforts on aforesaid lines.

They further undertake to assist one another with all political,

economic, and military means when one of the three contracting powers is attacked by

a power at present not involved in the European war or in the Chinese-Japanese conflict.

Until November 1941, the war between the Allied Nations and the Axis Powers was waged in Europe, North Africa, and China. On December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and shattered any American hope for neutrality, the conflict truly became a World War. Three days after the United States declared war on Japan, Germany issued its own declaration of war on the United States. The U.S. Congress quickly reciprocated in kind, setting the stage for the costliest war in world history. The British Empire, at last, had a powerful ally in its struggle against Hitler and fascism.

Winston Churchill eagerly welcomed America's entrance into the war that threatened the eastern hemisphere. He was quick to remind President Roosevelt of his promise a year earlier that, in the event of a two-front war, priority would be given to the campaign against Adolph Hitler. During the last week of December American, Canadian, and British war planners met in Washington, D.C., for the Arcadia Conference to determine how best to implement War Plan ABC-1, the promise to fight the European war first. It was during that conference that planning for an invasion of North Africa first surfaced, though most American commanders promptly rejected it.

The one positive strategy that emerged from the North Africa dialog was the concept of using aircraft carriers to transport Army Air Force land-based bombers close enough to North Africa to establish active airfields. Beyond that, the idea of a North African amphibious assault quickly lost popularity to a preferred cross-channel invasion. But the concept of shipping bombers into the theater to be launched near land from aircraft carriers provided the missing element to fulfilling FDR's call for a bombing raid on Japan. The result was Doolittle's bombing raid from the deck of the USS Hornet three months later.

President Roosevelt promised that American troops would be committed to the war in Europe before the close of the year (1942). Even so, both Churchill and Roosevelt realized it would take months for the United States to raise, train, equip and field an army capable of crossing the English Channel for an invasion of Northern France. Thus, that main offensive was initially planned for early in 1943.

Meanwhile, Hitler's blitzkrieg was stalled by winter weather only a few hundred miles from Moscow on the Eastern Front, and there was good reason to believe that with the coming of summer the Soviets might quickly succumb. With his own regime crumbling beneath the onslaught, Joseph Stalin pressured the Allies to invade and open a second front that would force Hitler to divide his forces, thus relieving pressure on Moscow. While it might be observed that Moscow was getting its just deserts for dealing with the devil, the fall of the U.S.S.R. would have been disastrous for the entire Allied effort.

General George C. Marshall was particularly sold on the idea of a 1943 cross-channel invasion, as were most of the other top military commanders. Thus, this was the strategy adopted at the Arcadia Conference. Meanwhile, the 33rd Fighter Group of the U.S. Army Air Force was sent, with their new P-40 Tomahawks, to bolster Allied efforts to turn back Erwin Rommel in North Africa. The U.S. 34th Infantry Division was shipped to Northern Ireland to begin a year of training for the proposed 1943 invasion of Northern France. By summer they were joined by the 1st Infantry and 1st Armored Divisions, but the turning tide of events was prompting the two leaders who mattered most to push anew for an invasion of North Africa.

The Japanese own version of blitzkrieg in the Pacific in the early spring had pushed all the way to New Guinea. Japan was poised for a strike at Australia. Under this threat, the Australians called for the return of their own forces fighting in North Africa. Ultimately the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions returned to defend their homeland, leaving only the 9th Division to try and turn back Field Marshall Rommel.

Both President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill renewed their calls for a North African invasion, convinced by now that the Mediterranean must be secured. They were also convinced that such an action was the key in the drive to defeat Germany. They reasoned that with North Africa in Allied hands, devastating bombing raids could be mounted to destroy Hitler's war machine. If the Allies could take control of the important Tunisian port at Tunis, it could become the staging area for assaults across the Mediterranean into Sicily and Italy. The Allied forces could then attack Germany from its soft underbelly.

While the British and American Combined Chiefs of Staff continued the debate about how best to go on the offensive, the two men at the top settled the question. Sometime in the last week of July, Churchill and Roosevelt ordered their commanders to prepare to invade North Africa before the end of the year. This controversial decision effectively postponed the more popular idea of a cross-channel assault until 1944.

Three weeks later the wisdom of this decision was proven when 50 U.S. Rangers, 1,000 British Commandos, and 5,000 Canadian soldiers made the ill-fated cross-channel attack on the French port of Dieppe. A colossal blunder at the command level, resulted in 50% casualties for the Allied Forces. One out of every five Canadian soldiers was killed in the nine-hour effort. Had D-Day, and the landings in Northern France occurred in 1942, what became the war's most famed amphibious assault may have well been the war's greatest disaster.

While the decision to proceed with the North Africa landing, at last, settled the question that had plagued Allied planners for months, it raised a host of new questions, all with potentially disastrous consequences:

• From where could such an invasion be launched?

The only dry land remotely near North Africa that was still in Allied hands was the peninsula of Gibraltar that jutted into the Mediterranean Sea from the coast of southern Spain. The British possession was too small to stage an invasion and was closely watched by Axis spies who would quickly warn Hitler of any unusual Allied buildup. An invasion of the size being proposed could never be launched from Gibraltar. It had to come from afar.

• How long could the Russians hold back Hitler's forces on the Eastern Front?

If the Soviets, already on the brink of collapse, fell to the invaders, Hitler would be free to turn back his massive army on the Eastern Front to meet and crush the Allied invasion.

• How would the Spanish respond to such an Allied invasion?

Though neutral, Francisco Franco was obviously friendly towards the Axis. If Franco responded to an Allied invasion by opening his bases for use by the Axis, enemy airpower could quickly be rushed into the area to destroy the Allies. The matter was further complicated by a small strip of land on North Africa where the Mediterranean Sea narrowed to meet the Atlantic called "Spanish Morocco". A Spanish colony, it was the only neutral land in a region otherwise belonging exclusively to France.

• How would the French react to the invasion?

This, of course, was the major question. Following the occupation of Paris and the Armistice with Hitler in 1940, a pro-Axis puppet government had been established to conduct the affairs of France including the defense of its colonies in North Africa. Two of these, Morocco and Algeria, were planned sites for the Allied landings in North Africa. The key question for the Allies was: Would the French welcomed the liberators with cheers and smiles, or with bullets and bombs?

The Vichy Government of France

The 1940 Armistice that ended German aggression in France and brought the French people under an army of occupation was but one more deal with the devil. Under that Armistice, Germany was granted control of three-fifths of France. In France, an Axis-friendly government was established under Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain in the southern resort city of Vichy. But for the French National Forces under General Charles de Gaulle, and a courageous underground resistance movement, the French were thereafter aligned with the Axis.

The 1940 Armistice that ended German aggression in France and brought the French people under an army of occupation was but one more deal with the devil. Under that Armistice, Germany was granted control of three-fifths of France. In France, an Axis-friendly government was established under Marshal Henri Philippe Pétain in the southern resort city of Vichy. But for the French National Forces under General Charles de Gaulle, and a courageous underground resistance movement, the French were thereafter aligned with the Axis.

Under the terms of that armistice, the Vichy government was allowed to maintain enough of a military force to protect its colonies. Nazi occupation troops monitored the French military to ensure it could not rebuild to mount a rebellion. Though the French were denied new equipment or parts for their aging military forces, the Vichy still fielded a respectable armed presence. In French Morocco alone, one of three proposed landing sites for the planned Allied invasion, there remained an army of 55,000 supported by 160 light tanks, 80 armored cars, artillery batteries, and 160 fighter aircraft. Sheltered inside the great port at Casablanca was one French cruiser, three large destroyers, seven additional destroyers, and the as-yet-unfinished but combat-capable battleship Jean Bart. Churchill and Roosevelt also knew that a similarly formidable French/Algerian force could be quickly mounted to repulse any Allied invasion at the two other proposed landing sites, Oran and Algiers.

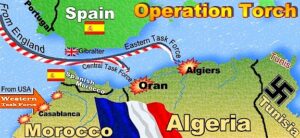

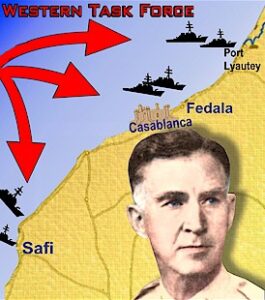

Code-named "Operation Torch", the invasion of North Africa quickly became a complex and daring strategy under the overall leadership of Lieutenant General Dwight Eisenhower. American soldiers in North Ireland and England, who had been training for a 1943 cross-channel assault, saw their timetable shortened by six months and their destination moved hundreds of miles south. In all nearly 50,000 American and 23,000 British troops planned to sail south to enter the Mediterranean through the Straits of Gibraltar, and then land near the Algerian ports at Oran and Algiers. A Western Task Force of 35,000 American soldiers under the ground command of Major General George S. Patton was tasked with landing at three locations along the coast of French Morocco to seize control of the ports at Safi and Fedala, and the important airfield at Port Lyautey.

Code-named "Operation Torch", the invasion of North Africa quickly became a complex and daring strategy under the overall leadership of Lieutenant General Dwight Eisenhower. American soldiers in North Ireland and England, who had been training for a 1943 cross-channel assault, saw their timetable shortened by six months and their destination moved hundreds of miles south. In all nearly 50,000 American and 23,000 British troops planned to sail south to enter the Mediterranean through the Straits of Gibraltar, and then land near the Algerian ports at Oran and Algiers. A Western Task Force of 35,000 American soldiers under the ground command of Major General George S. Patton was tasked with landing at three locations along the coast of French Morocco to seize control of the ports at Safi and Fedala, and the important airfield at Port Lyautey.

Never before in history had a force so large (numbering more than 100,000 men), staged for a mission so far from their objective (1,500 miles from Britain and 3,000 miles from America), to establish a beachhead so vast (nearly 1,000 miles). If the landings were successful the Allied forces could quickly move eastward to capture the important port at Tunis, then reinforce and relieve the battered British forces in Egypt, and ultimately chase Erwin Rommel out of Africa. If the landings failed it might well signal the end of all hope for turning back the fascist tide of the Axis.

Perhaps the single most important element to the future of democracy could be found in the answer to the question of the French resistance. If, when the invasion began, the Vichy remained loyal to the Axis, their aircraft in North Africa might overwhelm the ground forces and wreak havoc on the naval armada that brought the Americans. If, on the other hand, the French could be convinced to welcome the Americans as bringing liberty from Axis oppression, there was a strong chance for success. Though the answer to the French question eluded everyone, planning for the invasion continued with the Western Task Force slated to depart from Virginia on October 23. That element's ground commander, General George Patton, aptly summed up the task when he stated, "The job I am going on is about as desperate a venture as has ever been undertaken by any force in the world's history."

D-Day was set for November 8.

The Diplomat and the General

Mr. Robert D. Murphy was a dedicated and skillful United States diplomat in Algiers. Even after the 1940 Armistice that changed the seat of power in France, the United States had maintained diplomatic relations with the Vichy government and Mr. Murphy had played an important role in encouraging Operation Torch, the North Africa invasion, despite its complicated political considerations and unanswered questions.

Mr. Robert D. Murphy was a dedicated and skillful United States diplomat in Algiers. Even after the 1940 Armistice that changed the seat of power in France, the United States had maintained diplomatic relations with the Vichy government and Mr. Murphy had played an important role in encouraging Operation Torch, the North Africa invasion, despite its complicated political considerations and unanswered questions.

Major General Mark Clark was a good soldier in search of the answer to those questions. To find them he flew first to Gibraltar. There he boarded British submarine HMS Seraph on October 19 for a clandestine meeting with Vichy leaders in his own desperate mission to save American and French lives.

Two days after departing Gibraltar the Seraph surfaced at 4 a.m. only five miles off the African coast near the port of Cherchel. In the pre-dawn darkness General Clark, along with Brigadier General Lyman Lemnitzer and a few other high-ranking officers, were carefully rowed to shore by British Captain Dicky Livingstone and other volunteers from the Special Boat Service. Upon landing they were greeted by Mr. Murphy, who quickly escorted them to a small villa to hideout through the day.

Under cover of the night, the small group of American flag officers and their British escorts slipped into Cherchel and gathered in a villa owned by a local Frenchman who was anxious to see his country free of the Axis occupation. When dawn broke the commander of the Vichy French ground forces in Algeria, Major General Charles Mast, arrived to meet with General Clark. As the owner of the villa, General Mast was friendly towards the Allied aims. Both men were facilitating the clandestine meeting with Clark at great personal risk.

Clark briefed Mast on the impending invasion of North Africa while walking a tight rope of giving enough information to convince the commander of the Vichy forces as to the wisdom of cooperating with the Americans while maintaining enough secrecy (date/time/place of the invasion) to avoid compromising security. General Mast agreed loosely to support the American effort while hedging enough to protect himself if problems developed. Aware that even on his own orders some of the loyal Vichy soldiers might resist the landing, Mast suggested that the Americans obtain the support of General Henri Giraud.

Giraud was a French hero, a four-star general who had fought the Germans in two wars and been captured and escaped in both. Following the French/German Armistice, Giraud had been permitted to retire in southern France where he was still held in awe and respect by his countrymen. Mast was convinced that if the Americans could strike a deal with Giraud, an agreement by which the General would issue orders not to resist the Torch landings, the French, Moroccan and Algerian forces would not fire on the American landing.

General Mast met with Clark and Murphy for only a few hours and then returned to his headquarters before reveille. He left behind a small contingent of loyal French officers who spent the day briefing the Americans on the French forces in the region, including their best guesses as to which forces would resist the landings, and from what areas opposition would be mounted. In general, it was assumed the most resistance would come from the French naval forces under Admiral Jean Francois Darlan. All of that which was learned was critical intelligence information that would prove pivotal in the success of Operation Torch.

The cloak-and-dagger episode took a dangerous twist when night fell. Clark and his small group were preparing to return to their kayaks when they were warned that local police were on their way to the villa. A local worker had noticed the strange and suspicious events at the villa throughout the day and had notified the authorities. When they did arrive as the Americans had been forewarned, it was to find Robert Murphy and his vice-consul singing loudly and drinking heartily with some French friends. Meanwhile, Clark and his entourage hid in the cellar below. Despite the fact that the police appeared only to have stumbled on a loud party, for two nervous hours they nosed suspiciously around.

Shortly before midnight, it was safe for Clark and his small group to slip quietly back to the beach. There they tried to launch their kayaks into heavy surf. After capsizing in the dangerous waters, the drenched men returned to the beach to find a better launch point. Finally, at 4 a.m., the men were able to row back to the Seraph. Their dangerous and harrowing mission was completed.

Two days later General Clark was back in London to brief General Eisenhower and to divulge the wealth of intelligence information he had obtained. Ultimately, the daring officer was awarded the first of three Distinguished Service Crosses for his secret mission to Algeria. Robert Murphy also received the DSM, one of only sixteen awarded to American civilians in World War II. Together with the American officers who had accompanied him and the British Boat Service volunteers who had joined them in the risky venture, Clark formed what the daring men called the "African Canoe Club".

Meanwhile, convoys totaling more than 600 ships departed from England, North Ireland, and the United States. They carried more than 100,000 soldiers, men on a mission to keep their date with destiny on the sands of North Africa. Such major military activity could not be kept completely secret, and both Allied media and German war planners were busily doing their best to guess at what was happening, and what could be the destination of so large a force. By the end of October Task Force 34 bearing General Patton and his soldiers had completed nearly half of their 3,000-mile Atlantic crossing and the remaining two task forces were nearing the Straits of Gibraltar. In London General Eisenhower prepared to move his headquarters to Gibraltar, which was now crammed with Allied aircraft. The HMS Seraph was en route to South France to board General Giraud and ferry him to Eisenhower's headquarters.

The dealings with General Giraud, which had been recommended earlier by an overly-optimistic General Mast, were proving to be both necessary but extremely complicated. Since the Armistice great hostility had arisen between the French and Great Britain. The British were sorely disappointed in the French for submitting to the Axis in the Armistice, while the French saw the evacuation from Dunkirk as the British deserting them to stand alone against the onslaught. Following the Armistice, Britain had feared the consequences of French naval resources being taken by the Axis and turned against them. To prevent this Britain and launched Operation Catapult. French ships in Allied ports were seized by British forces, and a large French fleet was attacked at the French naval base at Mers-el-Kebir near Oran in Algeria. In that latter action alone, more than 1,000 French sailors were killed...by ships of the British Navy. Two old allies from the first world war were now bitter enemies, each with the blood of the other on its hands.

Realizing that the Vichy would most certainly resist a British landing force, every effort had been made to convince the French that the Torch invasion was a purely American operation (though British commanders, ships, and 23,000 soldiers were actually involved). The American flag was sewn on the sleeves of the American soldiers destined to make the landings, and British ships in the transport convoys actually flew the Stars and Stripes. Aboard the transports taking soldiers to the landing beach near Oran was a 4-man mortar crew with an unusual armament--shells designed to launch a pyrotechnic display that would transform into a 100-foot long American Flag high over the landing site to advise the locals that it was Americans who were arriving on their shores.

The irascible General Giraud had refused to slip out of Southern France and into Eisenhower's headquarters on a British submarine. For this reason, American naval Captain Jerauld Wright was placed "in command" of HMS Seraph's British crew, despite the fact that the American officer had no experience in submarines. On November 1 Giraud insisted that he could not leave France for three weeks and asked Eisenhower to delay the invasion until November 21. With his ships already en route, the American commander advised that he would not risk his men or ships. The landings, he stated to Giraud, would proceed on schedule, with or without the French general. Ike then packed his belongings and prepared to depart London on the following day. It was not to be.

When General Eisenhower arrived at Bournemouth on the evening of November 2 to fly to his new headquarters in an Air Force B-17, the weather grounded him for the evening. He returned to London hoping for a break in the weather and diverted his attention that evening by watching a movie. While German spies and Allied media prognosticators tried their best to guess what Eisenhower's force was up to, it is ironic that the movie that gave the General cause for laughter on his last night in England was a new Bob Hope/Bing Crosby release titled, "The Road to Morocco".

The Banker

If General George Patton believed his role as ground commander for the invasion force headed to Morocco was a desperate venture, he could not have more aptly described the mission assigned to the Army Air Force major accompanying the Western Task Force. General Truscott firmly hoped that the brokering skills of Major Pierpont Hamilton, a former international banker, could make Patton's venture less desperate and save hundreds of lives in the process. Truscott was assigned to lead his element of Patton's Army ashore at Port Lyautey, one of three Allied objectives on the Moroccan coastline.

If General George Patton believed his role as ground commander for the invasion force headed to Morocco was a desperate venture, he could not have more aptly described the mission assigned to the Army Air Force major accompanying the Western Task Force. General Truscott firmly hoped that the brokering skills of Major Pierpont Hamilton, a former international banker, could make Patton's venture less desperate and save hundreds of lives in the process. Truscott was assigned to lead his element of Patton's Army ashore at Port Lyautey, one of three Allied objectives on the Moroccan coastline.

Born in Tuxedo, New York, on August 3, 1898, Pierpont Morgan Hamilton groomed himself for success. Following day school in New York City and subsequent classes at Groton School, he enrolled at prestigious Harvard University in the fall of 1916. The next year the United States entered the First World War and Hamilton left school to join the Army Signal Corps Aviation Section. Since he would not celebrate his 19th birthday until August of that year, he was forced to sit out the summer awaiting assignment. While he did so he helped the NYC Police Commissioner, Colonel Arthur Woods, organize a wartime harbor patrol. Colonel Woods had married Pierpont's sister Helen the previous year so the two men were not only friends but brothers-in-law.

Pierpont Hamilton took flight training at Hazelhurst Field on Long Island in the fall where he soloed after only forty minutes of dual flight instruction. A brief bout of ptomaine poisoning prevented his October departure for overseas duty and, upon recovery, he was sent to Ellington Field near Houston, Texas, to complete his training. Hamilton earned his commission as a second lieutenant on May 9, 1918. Six months later the war ended and Lieutenant Hamilton returned to civilian life on December 31 with an honorable discharge.

Returning to Harvard he earned both bachelor's and master's degrees before joining the foreign department of a New York bank. In the interim between wars, he spent six years in Pairs with an international banking house, during which time he became fluent in the language and gained a keen understanding of French culture and thinking.

In 1938 Hamilton was president of Dufay Color, Inc., the American subsidy of a British firm that was working in the field of color photography when war broke out in Europe. While the United States maintained neutrality until December 1941, many young American boys sought to fight the spread of fascism as members of the British RAF and the Canadian Air Service. Hamilton's years of foreign service suited him well, and he spent much of those years establishing the Canadian Aviation Bureau which tested and prepared these American volunteers for foreign combat service.

Four months after Pearl Harbor Hamilton returned to active duty as a major in the U.S. Army Air Force. His sons followed their father in the defense of freedom, Philip as a Naval Reserve aviator, David as an Army Air Force pilot, and Ian as a Marine Corps aviator. While his sons trained and prepared for military service, Major Hamilton traveled to England as one of the U.S. officers attached to the Combined Operations staff of Lord Louis Mountbatten. During the summer his duties included the planning for the ill-fated August Dieppe Raid.

Hamilton's experience, international prowess, understanding of the French, and lessons learned from the Dieppe Raid made him a valuable man for the North Africa invasion. He returned home in October, just in time to sail with General Patton's Western Task Force (TF-34).

Though the ultimate objective of the Western Task Force was the city of Casablanca, it was not numbered among the three Moroccan landing sites of Operation Torch. Upon nearing the coast Task Force 34 split into three sub-groups. The Southern Group sailed 140 miles south of Casablanca to take the port city at Safi, the only port suitable for unloading American tanks. General Patton's Center Group was ordered to land at the small port city of Fedala 16 miles north of the well-fortified Casablanca objective. With tanks moving in from the south after unloading at Safi, Patton hoped to encircle Casablanca and force its capitulation without a major battle.

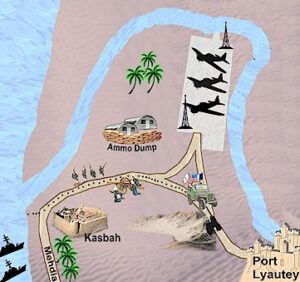

The objective for General Truscott's Northern Group was the beaches at the resort city of Mehdia Plague, 80 miles north of Casablanca. A short distance further inland lay Port Lyautey. Shipping reached that city, five miles inland, via the Sebou River which followed a winding route past the old Portuguese Kasbah Fortress and the Port Lyautey airport. The landing field was a critical objective of the success of the invasion. Not only did it serve as an important staging area from which the French might launch overwhelming air power to turn back the Allied invasion, but its lengthy runways were also the only concrete strips in the region suitable to all-weather operations by big American bombers.

The objective for General Truscott's Northern Group was the beaches at the resort city of Mehdia Plague, 80 miles north of Casablanca. A short distance further inland lay Port Lyautey. Shipping reached that city, five miles inland, via the Sebou River which followed a winding route past the old Portuguese Kasbah Fortress and the Port Lyautey airport. The landing field was a critical objective of the success of the invasion. Not only did it serve as an important staging area from which the French might launch overwhelming air power to turn back the Allied invasion, but its lengthy runways were also the only concrete strips in the region suitable to all-weather operations by big American bombers.

During the convoy's three-week voyage from the American East Coast to Morocco, General Truscott worked with Major Hamilton to lay out the details for an important mission he hoped would ensure the success of his landing. A personal message from General Truscott to the French commander at Port Lyautey was drafted, transcribed into French, rolled, and wrapped with a ribbon. The message called for the Vichy officer to order his men not to fire on arriving American soldiers. Major Hamilton volunteered to land with the first wave of assault forces bearing a white flag of truce. Private Orris Correy volunteered to drive Hamilton's jeep inland ahead of the invasion to personally deliver the message. General Truscott hoped Hamilton's fluent French, his international experience, and his brokering talents would convince the French commander to accept the written entreaty.

As the details were worked out, one of Truscott's top commanders began to pressure the general to let him join Hamilton in the desperate venture. Initially, Truscott refused; the new volunteer was a colonel assigned to command his air forces. He felt it unwise to risk so important a leader to a mission so potentially dangerous. The colonel persisted, pointing out that for the first few days of the invasion the Air Force compliment would see limited duty, and noting that he had plenty of capable officers.

Truscott could not deny that his air chief's presence could contribute materially to the success of Hamilton's mission. Furthermore, this new volunteer was experienced, quick thinking, and reputably unstoppable. At last, Truscott relented.

The Adventurer

Colonel Demas Nick Craw was the perfect complement to Major Hamilton. A career Army Air Force officer, he had been through more precarious situations in his life than one could imagine. A daring and scrappy fighter, he always managed to emerge from each unscathed.

Colonel Demas Nick Craw was the perfect complement to Major Hamilton. A career Army Air Force officer, he had been through more precarious situations in his life than one could imagine. A daring and scrappy fighter, he always managed to emerge from each unscathed.

Born in Traverse City, Michigan, at the turn of the century, Demas Craw lied about his age and joined the Army at seventeen. His enlistment was just in time to send him to the Mexican border with the Twelfth Cavalry during the tense border war of 1917. Itching for action, upon learning that a skirmish was developing at Nogales, Craw went AWOL (Absent Without Leave) to join the fracas. Soon thereafter his commanders learned his true age and he was promptly discharged and sent home. The following April he turned eighteen and enlisted legally, arriving in France in time to see action on the Marne and in the Argonne Forest with the Third Division. His courage was unmatched and he was promoted to the second lieutenant before returning home.

Though most young soldiers would be thrilled to receive a battlefield commission, for Craw it was a step backward. He did want to be an Army officer but, more importantly, he wanted to build a successful military career--the kind that required the right education. In order to qualify for West Point, he gave up his temporary commission and began attending night classes to prepare himself academically. In 1920, after passing his exams, he was appointed to the Class of 1924.

Though most young soldiers would be thrilled to receive a battlefield commission, for Craw it was a step backward. He did want to be an Army officer but, more importantly, he wanted to build a successful military career--the kind that required the right education. In order to qualify for West Point, he gave up his temporary commission and began attending night classes to prepare himself academically. In 1920, after passing his exams, he was appointed to the Class of 1924.

It was at West Point that Demas Craw earned the nickname that followed him for the rest of his life, a welcomed moniker since he had never been fond of his given name. Initially, fellow cadets called him "Nicodemas"; which was soon shortened to "Nick". For the rest of his life, Demas Craw became Nick Craw.

Though Nick Craw excelled in sports, in fact, it seemed--in EVERY sport, academics were not so easily mastered. With determination, he worked hard, accepted tutoring from a fellow cadet, and on June 12, 1924, graduated 271 out of his class of 405. Commissioned an infantry lieutenant, Craw requested a transfer to the Army Air Corps where he became an avid flier.

Nick Craw's early career was unimpressive and mundane; he was just one more air officer in an experimental air force. In 1939 Craw was flying a desk as a member of the Air Corps staff in Washington, D.C. when fighting began in Europe. Early the following year he was ordered to Egypt as an American observer of the Royal Air Force's combat actions against Germany. For Nick Craw that role meant more than sitting behind a desk and writing reports, it meant going where he could watch the RAF in action. Long before the United States entered World War II Craw had flown twenty-two air missions against the Axis.

Craw was with the RAF in Athens when German forces overwhelmed the island early in 1941. When Craw's retreating British friends informed him that a seat on an airplane to safety was being reserved for his departure, he declined the offer. Nick felt that his own departure would deny some other British pilot evacuation. The RAF left without Demas Craw.

One day later he was approached by two British ground officers and a Greek who had been unable to get off the island. The men informed him they had found and repaired an old, two-engine Anson bomber but that they needed a pilot. Throughout the night and into the following morning the four men worked to prepare their rescue plane for takeoff, only to see it destroyed by a dawn strafing attack by a formation of Stukas. "They really plastered us," Craw later recalled. "They killed the Greek and wounded one of the British. I never ran so fast in my life."

A short time later Craw and the unarmed British soldier were captured while trying to get their wounded comrade to a nearby seaport. Interred together for a brief time by the German forces, Craw was subsequently released when his West Point ring identified him as the citizen of a neutral nation. In the days that followed his release, he remained in occupied Athens, moving about freely and observing all that was going on around him.

In his youth Craw had been an unstoppable fighter, excelling in boxing at West Point. While still in occupied Athens he created something of an international incident after an Italian major accidentally side-swiped his car. The angry officer ordered two of his men to restrain Craw while he slapped him across the face. Craw wrenched his arms free and dropped the Italian to the ground with a single punch. One of the nearby soldiers raised his rifle to deliver a butt-stroke but Craw was faster, dropping his second opponent in less than half a minute.

The scene attracted the attention of a nearby German officer who promptly intervened. Craw explained he had been insulted by the Italian major's lack of respect in slapping an officer of a neutral country, and informed the now-standing major he was ready to finish the job at any time he wished. The major declined to say he was too busy. Craw responded, "All I need is ten square yards and one minute."

The following day after a report of that incident reached the American foreign minister in Athens, the Italian major arrived at the American legation to tender his apology. Doubtlessly, those who knew Craw had all they could do to keep from smiling during the sober event. The Italian major was sporting a highly prominent black eye.

The following year when Craw sailed with Patton's Task Force 34, he was a full colonel, an experienced and well-respected leader, and a man with a good understanding of the varied cultures in the Mediterranean. Despite his short fuse, he was possessed of good judgment and self-control. He could be diplomatic in the pursuit of the special mission he had volunteered for, but if the bottom fell out of diplomacy, he was the kind of fighter any soldier would love to have on his side.

General Eisenhower and Mark Clark managed to fly out of London to establish the invasion headquarters on Gibraltar on November 5. They departed in a B-17 flown by a young pilot named Major Paul W. Tibbets, the man who three years later dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima. The last of what should have been six flying fortresses taking off that morning to relocate Eisenhower's headquarters was forced to return to London. It departed the following day, only to be plagued by worse problems. Halfway to Gibraltar the lone B-17 was attacked by four German Junker JU88s. The airborne Flying Fortress had been stripped to ferry Eisenhower's staff so there were few guns and no experienced gunners to return fire.

Brigadier General Lemnitzer, who had accompanied Mark Clark on his earlier mission to North Africa, fiddled with the one remaining gun in the radio compartment and figured out how to shoot back. Meanwhile, pilot John Summers dropped to sea level to evade the flaming guns of the enemy. The Junkers dove ahead then came streaking in on a collision course with their own machine guns blazing. The cockpit window shattered, spraying shards of glass over the pilot and co-pilot. Nearly blinded, Summers yelled for the passenger behind him to help him move the injured co-pilot. That officer did so, then settled his own short, stocky frame into the co-pilot's seat. Sun glinted off the two stars on the new co-pilot's collar but the flag officer silently hoped that Summers could sustain long enough to get the now crippled flying fortress to Gibraltar. Major General Jimmy Doolittle, the new commander of the recently formed 12th Air Force, had never piloted a B-17 before and hoped he would not have to learn the hard way.

Fortunately, the German fighters broke off, and, despite the flow of blood into his eyes, Lieutenant Summers remained at the controls all the way to Gibraltar. Doolittle logged his first mission as commander of the 12th Air Force: two hours of combat flight as the co-pilot of a B-17.

With 24 hours before D-Day, things began to seemingly fall apart. Eisenhower assembled his staff at Gibraltar to discuss the matter of Spain, worrying that when the offensive began Francisco Franco might offer his allegiance and Spain's ports and airbases to the Axis. To avoid provoking Spain he issued orders, "Do not pick a fight with the Spanish in any way."

At the eastern edge of the Atlantic, a brewing storm began pummeling Task Force 34, threatening to postpone the landing. General Patton wired Eisenhower at Gibraltar to advise: "Don't worry (about the weather). If need be, I'll land in Spain."

During the early afternoon of December 7, General Giraud arrived at Gibraltar. He was escorted to meet Eisenhower. "Let's get it clear as to MY part," Giraud announced. "As I understand it, when I land in North Africa, I am to assume command of all Allied forces and become Supreme Allied Commander in North Africa."

Eisenhower, of course, could make no such concession and the two engaged in a heated hour-long debate. Without the concession from Eisenhower that the French General himself would command all Allied forces in North Africa, Giraud refused to give the order for the Vichy to cooperate. The debate resumed after dinner, degenerating into a shouting match. Finally, Giraud announced, "I shall return to France."

"Like hell you will," General Clark announced. "That was a one-way submarine you were on. You're not going back to France on it." After a moment of silence Clark advised Giraud through his interpreter, "If you don't go along (with the plan,) general, you're going to be out in the snow on your ass!" It was now 10 p.m., the invasion was only hours away, and the French question was still far from answered.

The commanders of the three task forces, now within miles of their objectives, responded to the problem with a two-fold rule of engagement. If a ground commander came under fire from the French forces, he was to radio headquarters with the phrase "Batter Up". Upon the response "Play Ball", permission was granted to return fire and engage the French.

By midnight all was in readiness. Near the port of Oran Major, General Lloyd Fredendall's Central Task Force began unloading its landing craft and preparing to transport General Terry Allen's 1st Infantry Division ashore. In all, the initial landing would contain 39,000 American soldiers. A few hundred miles to the east Major General Charles Ryder's 10,000 American and 23,000 British soldiers (under Lieutenant General Sir Kenneth Anderson) were already moving in the silent darkness towards the sandy beaches.

Along the coast of Morocco Major General Patton's 35,000 soldiers were readying themselves for a 4 a.m. assault, the words of their commander, spoken while en route, were still ringing in their ears:

"When the great day of battle comes, remember your training...you must succeed, for to retreat is as cowardly as it is fatal. Americans do not surrender.

"The eyes of the world are watching us. The Heart of America beats for us. God is with us. On our victory depends the freedom or slavery of the human race. We shall surely win."

Aboard General Truscott's flagship just off the coast near the Sebou River stood two men, the banker and the soldier, a Harvard man and a West Pointer, who both fervently prayed they would be equal to the challenge that lay before them.

Aboard General Truscott's flagship just off the coast near the Sebou River stood two men, the banker and the soldier, a Harvard man and a West Pointer, who both fervently prayed they would be equal to the challenge that lay before them.

Operation Torch

It was shortly after midnight that the landings at Oran and Algiers began in earnest. Over six hours during the early morning on November 8, 1942, more than 50,000 Americans and nearly half that number of British Soldiers (most wearing American uniforms) began streaming ashore.

Confusion and mechanical problems delayed many elements, but resistance was light allowing the bulk of the invasion force to occupy their beachheads with minimal resistance. The order by General Mast to his French forces not to fire on the arriving Americans certainly had an impact on the low casualty rates. That toll might have skyrocketed if the landing had been met with the full force of the Vichy military forces in Algiers.

Confusion and mechanical problems delayed many elements, but resistance was light allowing the bulk of the invasion force to occupy their beachheads with minimal resistance. The order by General Mast to his French forces not to fire on the arriving Americans certainly had an impact on the low casualty rates. That toll might have skyrocketed if the landing had been met with the full force of the Vichy military forces in Algiers.

Nonetheless, the landing American force did engage areas of resistance that took their toll of casualties on both sides. This was due in great measure to a level of confusion among the French in Algeria that even exceeded perhaps, the confusion that hampered the landing forces of the Americans. General Louis-Marie Koeltz, commander of the 19th Military District and senior to General Mast, issued orders to his soldiers, "Resist any invasion by foreign troops with all means at your disposal." He also fired General Mast from his command of the Algiers Division and ordered the arrest on the sight of the pro-American general.

In the field, some French units received Mast's orders to cooperate, and their positions were often taken without bloodshed. French troops that received General Koeltz's contradictory directive to resist, often found themselves fighting heated skirmishes that were deadly to both sides. Some French commands received both contradictory orders, leaving the French soldiers to struggle indecisively to determine which to follow.

Admiral Jean-Francois Darlan, commander-in-chief of all Vichy France forces were ever stationed, happened to be visiting in Algiers as Operation Torch was unfolding. Upon learning news of the American incursion from Daniel Murphy, he exploded. "I have known for a long time that the British are stupid," he shouted at the American diplomat, "but I'd have believed the Americans were more intelligent. Apparently, you have the same genius as the British for making massive blunders."

An order from Admiral Darlan could have almost immediately halted all fighting between the Torch forces and the French defenders, all the way from Algeria to Morocco. Instead, Darlan informed Murphy, "For the last two years I have preached to my men in the Navy and to the nation, unity behind the marshal (Petain). I cannot now deny my oath."

Three days of see-saw fighting followed in Algeria, not only Americans vs. French, but the French among themselves. Pro-Allied rebel forces assisted landing American forces by taking key seats of Vichy power and capturing pro-Axis or loyal Vichy leaders. The loyal Vichy in turn responded by arresting a number of their own commanders who had "committed acts of treason against the Vichy regime," among them General Mast. At Gibraltar the stubborn and uncooperative General Giraud, whose order might have solved the problem once and for all, slept soundly through the opening hours of the operation.

The Road to Morocco

The Central and Eastern Task Forces that landed in Algeria faced some serious and deadly resistance. Still, there was no doubt that General Mark Clark's clandestine meeting with pro-Allied leadership in Algeria three weeks before the invasion had been instrumental in lessening that resistance, and had garnered some important allegiances for the Allied effort. No such mission had been mounted to seek cooperation from pro-Allied French leadership in Morocco, and it was there that the soldiers of Torch met some of their heaviest resistance.

Shortly after midnight Major General Emile Bethouart, commander of the Casablanca Division, advised his troops of the impending American invasion and ordered them to remain in their barracks. He then drove the 50-mile distance to Rabat to enlist cooperation from the battalion of Moroccan infantry guarding the capitol "in the name of General Henri Giraud." The invocation of the esteemed French hero's name garnered quick acquiescence from the infantry commander. Major General Louis Lahouelle, commander of the French air forces, agreed that his pilots would likewise not resist if the French Navy also cooperated with the landing. He placed a call to Vice Admiral Francois Michelier back in Casablanca.

"(General) Bethouart is a stupid and naïve victim of an elaborate Allied hoax," Michelier advised Lahouelle. "There is no American armada lying offshore. The weather is bad, the surf is high, and my coastal and submarine patrols have not spotted any ships offshore."

Admiral Michelier ordered the arrest of General Bethouart. Having just denounced the invasion as a hoax, he never-the-less issued orders to all troops throughout Morocco:

"Resist any invaders with every means at your disposal."

Operation Blackstone

Meanwhile, American forces of the Western Task Force were moving in on the important docks at the port of Safi. Shortly after midnight, the submarine USS Barb surfaced only a few miles from the port to unload rafts containing scouts from the 47th Infantry. Their job was to light the harbor entrance for the USS Cole and USS Bernadou. Unfortunately, the scouts became lost in the darkness and then skirmished briefly with a French patrol. At sea, confusion reigned when troop transports had troubles unloading. These unforeseen troubles pushed the landing schedule back four hours. Not until 4 a.m. was the Cole and Bernadou able to steam into the harbor to unload. They were met by a hail of enemy fire from numerous coastal guns and a 155mm battery just south of the city.

Further out to sea the signal "Play Ball" was given, authorizing the battleship New York to begin shelling the French positions. By dawn, Major General Ernest Harmon paced confidently up and down the docks in the small port city while his tanks began unloading. His men of the 45th Regiment, 9th Infantry Division dispersed through the city in a house-to-house running battle that soon saw them in control of the rail yard, the post office, and the police station. Though fighting would continue in outlying areas for days, when the sun rose over Morocco on the morning of November 8, it was to reflect off the Stars and Stripes waving proudly over the important port city of Safi.

Operation Brushwood

Far more resistance was expected at the landing sites near Fedala, a four-mile beachhead at the resort city 16 miles north of Casablanca and just south of the Moroccan capital of Rabat. It had been selected because it was not as heavily defended as was Casablanca, and Allied hopes were to take Casablanca with a minimum of destruction to the important port. Rabat had been ruled out as a landing site out of fear that an assault on the capital would be counter-productive to the desired perception of the landings being a liberating army, not an invading army.

Far more resistance was expected at the landing sites near Fedala, a four-mile beachhead at the resort city 16 miles north of Casablanca and just south of the Moroccan capital of Rabat. It had been selected because it was not as heavily defended as was Casablanca, and Allied hopes were to take Casablanca with a minimum of destruction to the important port. Rabat had been ruled out as a landing site out of fear that an assault on the capital would be counter-productive to the desired perception of the landings being a liberating army, not an invading army.

Joining the first wave of 3rd Infantry soldiers under Major General Jonathan Anderson was Colonel William Hale Wilbur. A West Point Infantry officer from the class of 1912, Wilbur had volunteered to go ashore to seek cooperation from the French. In the pre-dawn darkness, illuminated only by the exploding shells and tracers that greeted the first soldiers to reach the shoreline, Colonel Wilbur commandeered a jeep when his own failed to start and headed into the muzzles of the French. So heavy was the resistance that between the shelling and the heavy surf, 62 of the landing party's 116 assault boats were sunken or wrecked.

While desperate young American boys struggled ashore behind him, Wilbur charged through the French line of resistance to find an officer. He advised that he was carrying a message from General Patton to the French commander in Morocco, and was afforded passage south, traveling across 16 miles of hostile beach in his own desperate mission.

In Casablanca, Colonel Wilbur learned for the first time that the American-friendly General Bethouart had been arrested. His replacement, General Raymond Desre, refused to accept the letter from Patton. Frustrated, Wilbur found a French officer who offered to drive him to meet with Admiral Michelier. They arrived even as American shells began falling from off-shore battleships. The man who had dodged enemy fire all morning to deliver this important message found himself now threatened by friendly fire. Heedless of the danger, and despite the fact that he was alone in the headquarters of the enemy, Wilbur demanded to see the Admiral. "Get the hell out of here," an irate officer responded, pointing towards the door. Realizing the futility of his mission, Wilbur began the 16-mile jeep trip back to the beachhead where the infantrymen of Patton's Brushwood force were struggling for survival.

As he neared the forward lines of the American advance Colonel Wilbur could see a hostile French battery that was dropping deadly charges on the American ships at sea. Working his way to a platoon of nearby American tanks, he took charge to personally lead them against the enemy position. Wilbur rode the lead M3 Stuart Tank through the barbed wire perimeter while a nearby American infantry platoon laid down covering fire. In the face of this attack, the enemy commander soon sent word to Wilbur that he was ready to surrender his position to American control. Within an hour the Stars and Stripes were hoisted over that fire-control center while the French soldiers looked on as prisoners.

For his heroic actions from Fedalia to Casablanca and then back to the beachhead again, Colonel William Wilbur was later awarded the Medal of Honor. It was the first to be awarded for action in the European theater in World War II. Before the morning was finished, two American Army Air Force officers would join him in that distinction.

Operation Goalpost

The mouth of the Sebou River leads inland to Morocco's second-largest port at Lyautey. The city and its nearby airport were defended by 3,000 French Legionnaires and Moroccan Tirailleurs. These forces were supported by heavy artillery, armored cars, and a few tanks. Port defenses included the formidably armed garrison at the old Kasbah Fortress near the beach, just north of Mehdia.

Though General Truscott's Operation Goalpost force of 9,000 soldiers, including three battalions of the 60th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, outnumbered the defenders, the landing would leave them completely exposed to enemy guns and highly vulnerable. Allied planners had noted that "It would be hard to pick out a more difficult place to assault in all of West Africa (than the beach area along with the mouth of the Sebou)."

These concerns were compounded shortly after midnight when communications between the troop transports carrying the Goalpost forces broke down, and Truscott lost contact with his men. In the darkness, the commander spent three hours moving across the dark waters in a small boat to board and issue orders on each of his five troop transports. This pushed H-Hour back to 4:30 a.m. Moments before that critical hour arrived, five fully-lit French cargo vessels steamed out of the mouth of the Sebou. Upon encountering the American ships one of them flashed the message:

"Be warned. They are alert on shore! Alert for 0500".

Indeed, the French forces ashore were prepared when the first landing craft made their way through the surf along the coast of the resort village of Mehdia. Further north, the flat-bottomed landing craft bearing Colonel Craw and Major Hamilton was meanwhile entering the channel of the Sebou River. Suddenly the first shells started to fall. Explosions rent the stillness of the early morning, brilliant flashes illuminated desperate American infantrymen as they waded ashore, and geysers of water spouted upwards around the landing craft.

Eager to thwart any attempt by the Americans to send ships up the river, the French heavily shelled the mouth of the Sebou, forcing Craw and Hamilton's barge to pull in close to the stone jetty that sheltered the opening from the sea. As the first rays of dawn reflected off the river, upstream the Americans noted the floating buoys of an anti-submarine net. They could travel no further by boat. When there came a brief respite in the shelling, the barge slipped back out to sea far enough to skirt the jetty and land its cargo on the beach south of the river.

Private Correy started the jeep as the launch moved into shallow water, and as soon as the ramp dropped in the surf he was driving across the soft sand towards the beach. Behind him, Major Hamilton was scooping up the three flags that had rolled off the jeep when it bounced down the ramp. He was wading ashore in knee-deep water. It took the major little time to rejoin the vehicle, which had sunk up to its axels in a marsh a few hundred feet from the shoreline. Correy rocked the vehicle while the two officers stood in the mire in their dress uniforms to try and push it out of the hole, heedless of the shells that continued to burst around them.

Dawn was breaking as they struggled to free the jeep, and from high overhead came the whine of a French airplane diving on their position. The three men scrambled for the protection of a nearby sand dune just as a line of machinegun bullets stitched the mud where they had stood a moment before. That first plane was followed by others. Craw, Hamilton, and Correy returned between strafing runs to try and free their vehicle. It was futile and their mission might well have ended there, but for Army engineers that had come ashore on the beach to their south. Upon noting the stranded lone jeep between them and the river, the engineers sent a bulldozer to tow it out of the muck.

Minutes later the jeep was on the solid surface of the highway that skirted the shoreline and then curved inward at the Sebou River. While Private Correy removed the water-proofing attachments to the engine and exhaust system, Major Hamilton unfurled the three flags the men had brought. When Correy completed his own tasks and returned to the driver's seat, Colonel Craw was seated next to him holding an American and French Flag. Major Hamilton seated himself in the rear with a white flag of truce. Beside him, Hamilton carefully guarded the briefcase containing the ribbon-wrapped message to the French commander at Port Lyautey.

Minutes later the jeep was on the solid surface of the highway that skirted the shoreline and then curved inward at the Sebou River. While Private Correy removed the water-proofing attachments to the engine and exhaust system, Major Hamilton unfurled the three flags the men had brought. When Correy completed his own tasks and returned to the driver's seat, Colonel Craw was seated next to him holding an American and French Flag. Major Hamilton seated himself in the rear with a white flag of truce. Beside him, Hamilton carefully guarded the briefcase containing the ribbon-wrapped message to the French commander at Port Lyautey.