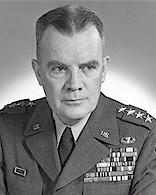

Hassell C. Whitefield

"Tough Ombres - Tender Heart"

The blood-red "T" and "O" on the patches of the men of the 90th Infantry Division when they stormed ashore at Normandy on D-Day reflected a World War I heritage linked to the states of Texas and Oklahoma. During that war, the 90th Division, largely composed of draftees from those two states, had fought their way bravely across France and into the Ardennes Forest. The valiant courage and individual sacrifice of these men netted 102 awards of the Distinguished Service Cross, 16 went to young soldiers from Oklahoma, and 22 to Doughboys who hailed from Texas. Though the division included many young patriots from across the nation, the 90th was indeed a Texas/Oklahoma unit.

The blood-red "T" and "O" on the patches of the men of the 90th Infantry Division when they stormed ashore at Normandy on D-Day reflected a World War I heritage linked to the states of Texas and Oklahoma. During that war, the 90th Division, largely composed of draftees from those two states, had fought their way bravely across France and into the Ardennes Forest. The valiant courage and individual sacrifice of these men netted 102 awards of the Distinguished Service Cross, 16 went to young soldiers from Oklahoma, and 22 to Doughboys who hailed from Texas. Though the division included many young patriots from across the nation, the 90th was indeed a Texas/Oklahoma unit.

When the United States again was propelled into a world war in 1941, the 90th Infantry Division was reactivated at Camp Barkeley, Texas, on March 25, 1942. The 90th trained first in Texas, then Louisiana and California, before sailing for England on March 23, 1944. Less than three months after their arrival, the T. O. soldiers found themselves crossing the English Channel for a year of bitter warfare, again forging their way across France, through the Ardennes, and into the German homeland.

Army Staff Sergeant Hassell C. Whitfield, a 20-year old native Texan from Erath County, was among the first members of the division to face the enemy, landing at Utah Beach on D-Day. Other members of the division continued to land over the ensuing days, attacking fiercely and demonstrating that the new generation of T. O. soldiers was every bit as tough as their fathers in the earlier war. So tough were they in fact, that on D-Day plus One when the troopship Susan B. Anthony struck a mine and was sunk near the approaches to Omaha Beach, the T.O. soldiers of the 2d Battalion, 359th Infantry, and Company C, 315th Engineer Battalion waded ashore without the loss of a single man.

Army Staff Sergeant Hassell C. Whitfield, a 20-year old native Texan from Erath County, was among the first members of the division to face the enemy, landing at Utah Beach on D-Day. Other members of the division continued to land over the ensuing days, attacking fiercely and demonstrating that the new generation of T. O. soldiers was every bit as tough as their fathers in the earlier war. So tough were they in fact, that on D-Day plus One when the troopship Susan B. Anthony struck a mine and was sunk near the approaches to Omaha Beach, the T.O. soldiers of the 2d Battalion, 359th Infantry, and Company C, 315th Engineer Battalion waded ashore without the loss of a single man.

For the men of the 90th Infantry, combat began in earnest on June 9 when Staff Sergeant Whitefield's 344th Artillery Battalion, along with the 90th's 345th Artillery Battalion, opened fire with their 105mm guns across the Merderet causeway in support of Glider and Parachute regiments of the 82d Airborne Division. It was the opening volley in what ultimately became 53-straight-days of continuous combat.

Members of the 90th Infantry fought their way across the Merderet, crushing the enemy resistance to attack into the Foret de Mont Castre. By sheer determination and sacrifice the forest was cleared by July 11 and the 90th pushed eastward, taking Periers on July 27.

On August 12 the division drove across the Sarthe River, capturing Chambois seven days later in the critical effort to close the Falaise Gap. Despite fierce fighting and heavy casualties, the T. O. soldiers continued their drive through Verdun on September 6 and engaged the enemy at Metz during a siege that lasted until mid-November. On December 6 the 90th pushed across the Saar and established a bridgehead north of Saarlautern inside southwestern Germany, where at last the division took up defensive positions to rest and replenish their ranks. In six months of bitter fighting, the 90th Infantry Division fought its way through every enemy obstacle, broke through the barrier into the German homeland, suffered nearly fifty percent casualties, and gained a new nickname. The "T" and "O" on their patch came to signify these soldiers as Tough Ombres.

It was a well-earned and descriptive moniker; in their first six months of combat, three Tough Ombres earned Medals of Honor and 58 earned Distinguished Service Crosses, including Division Commander Major General James Van Fleet who received an Oak Leaf Cluster to the DSC he had earlier earned while commanding the 4th Infantry Division.

The Bulge

By December 1944, Allied commanders considered the Ardennes Forest that stretched from eastern France into Belgium and Luxembourg a quiet area. For this reason, the lines were unusually thin, the long front extending for miles through the dense forest defended primarily by three U.S. divisions. Normally a division was responsible for the defense of a five-mile front, but with the Ardennes considered under control, the 106th Infantry was spread out over a 21-mile expanse of hills and timber. Matters were no better for the 4th and 28th Divisions, or the reduced elements of the 9th Division, that comprised the VIII Corps defense.

Adolph Hitler's unanticipated Ardennes Offensive began at 0530 with a massive artillery barrage in the pre-dawn shadows of December 16. Destined to be the bloodiest European battle of World War II, the majority of the nearly 20,000 Americans killed in the month-long campaign came in the first days. By December 19 the 106th Infantry Division's thin line suffered devastating losses, including the forced surrender of two full regiments.

By Christmas Day the surrounded Belgian city of Bastogne had become the focal point of all attention. Allied lines reeling under the surprise and massive enemy advance, the Germans demanded surrender from General Anthony McAuliffe, Acting Commander of Bastogne's 101st Airborne Division. General McAuliffe's gutsy one-word response "Nuts" ignited a determined response from General George Patton to reach Bastogne and relieve the pressure. McAuliffe's subsequent DSC citation noted: "Though the city was completely surrounded by the enemy, the spirit of the defending troops under this officer's inspiring, gallant leadership never wavered. Their courageous stand is epic. General McAuliffe continuously exposed himself to enemy bombing, strafing, and armored and infantry attacks to personally direct his troops, utterly disregarding his own safety."

By Christmas Day the surrounded Belgian city of Bastogne had become the focal point of all attention. Allied lines reeling under the surprise and massive enemy advance, the Germans demanded surrender from General Anthony McAuliffe, Acting Commander of Bastogne's 101st Airborne Division. General McAuliffe's gutsy one-word response "Nuts" ignited a determined response from General George Patton to reach Bastogne and relieve the pressure. McAuliffe's subsequent DSC citation noted: "Though the city was completely surrounded by the enemy, the spirit of the defending troops under this officer's inspiring, gallant leadership never wavered. Their courageous stand is epic. General McAuliffe continuously exposed himself to enemy bombing, strafing, and armored and infantry attacks to personally direct his troops, utterly disregarding his own safety."

As visibly evident as General McAuliffe's determination, and the courage of his command, were the details of the enemy offensive in printed maps that accompanied media reports of the battle. These maps revealed a bulge being forced into the Allied lines by the German advance, giving rise to the most-commonly recognized name for the Ardennes Offensive, the Battle of the Bulge.

While General Patton raced his Third Army to Bastogne, Allied war planners reacted swiftly to their own lack of foresight in anticipating the last, desperate German drive, promptly reinforcing the lines through the Ardennes. Among that reaction was the withdrawal of the 90th Infantry from their position inside southwestern Germany, and re-deployment along the lines in Luxembourg.

The Tough Ombres had a lot to be proud of, having broken the Seigfried Line and encamped inside Germany itself. The men of the division spent Christmas between the Saar and Moselle Rivers with orders to defend against reinforcement of the offensive in the north, while replacements arrived to compensate for the heavy losses in the previous months of fighting. New Year came and went, and five days later new orders arrived--"Be prepared for movement".

The following day the Tough Ombres began a cold 50-mile trek into the snow-covered mountains of Luxembourg. Secrecy shrouded movement, with vehicle identification masked to confuse German spies as to which Allied divisions were moving in what directions. Only the top commanders of the 90th knew the destination, which was along the line less than fifty miles south of Bastogne.

On January 9, two days after the 90th had begun its withdrawal to a new front, the division launched an assault to reduce the enemy salient south of Bastogne. The 90th's infantry regiments, supported by the division's artillery battalions, attacked through deep snow and bitter cold, catching the enemy totally unprepared. After three days of fighting, enemy communications were shattered in the sector, and on that third day alone, more than 1,200 German soldiers were captured. Documents were taken from these prisoners illustrated earlier Nazi concerns for the possible relocation of the Tough Ombres and the respect with which these fierce fighters were held. One captured German directive read:

"It is imperative that steps be taken to ascertain whether or not the American 90th Infantry Division has been committed (to the Ardennes Offensive). Special attention must be given to the numbers 357, 358, 359, 343, 344, 345, 915, and 315 (90th ID regiments). Prisoners identified with these numbers will immediately be taken to the Regimental G-3"

Unfortunately, by the time the Germans verified that indeed the 90th Infantry Division HAD been committed, it was too late. The Tough Ombres were exacting a heavy toll on the enemy salient. By the fourth day of fighting the 358th Regiment broke through into Belgium, linking with the 35th Infantry. The enemy salient in the south had been totally breached.

On January 14 the 90th Division, along with elements of the 26th Infantry and 6th Armored Division, attacked Niederwampach from two directions, quickly crushing all resistance and wresting control of the city from the Germans. Two days later the advance continued to gain control of the small but important town of Oberwampach.

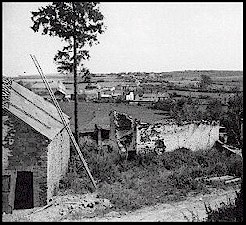

Oberwampach

Taking Oberwampach was tough enough, holding it would be another matter--and a deadly one. In the 36-hour battle that began on January 16, the Germans launched nine counter-attacks to drive the Tough Ombres out of the village. In that same period, Staff Sergeant Hassell Whitefield's 344th Artillery Battalion fired 6,000 rounds of heavy 105mm artillery rounds in defense, and tank battles raged on every approach into the strategic hamlet that only days earlier had been a German stronghold.

Taking Oberwampach was tough enough, holding it would be another matter--and a deadly one. In the 36-hour battle that began on January 16, the Germans launched nine counter-attacks to drive the Tough Ombres out of the village. In that same period, Staff Sergeant Hassell Whitefield's 344th Artillery Battalion fired 6,000 rounds of heavy 105mm artillery rounds in defense, and tank battles raged on every approach into the strategic hamlet that only days earlier had been a German stronghold.

Captain Arnold Brown commanded Company G, 358th Infantry Regiment, which had taken up positions inside Oberwampach. Brown had missed the Normandy actions, arriving as a replacement in August, but had fought through the last actions leading up to the crossing of the Saar. Getting into Oberwampach itself had been a deadly battle. At one point while moving across the open fields, his company came under direct machine-gun attack. Calling his radio-man to his side, Brown began calling for artillery. He was still barking instructions through the handset when the radio operator fell at his side, shot through the head. Finally, an American tank arrived to knock out the enemy position.

Upon moving into Oberwampach, Captain Brown quickly deployed his platoons in strategic positions on roof-tops or in the rubble that had once been a peaceful farming community. From there he was able to monitor the enemy's movement over one of the main routes into Bastogne. To coordinate his company's defense against the nine counter-attacks, mounted by infantry and columns of tanks and preceded by heavy artillery, Brown set up his command post inside a local home.

The Schilling family grudgingly welcomed the arrival of the American liberators, having suffered already from the gunfire, tank rounds, and artillery that had laid waste to the homes of friends and neighbors. The G.I.s who crammed into the small shelter took quickly to the family, and especially to the Schilling's five-year-old son. In addition to Captain Brown and other key members of his staff, Staff Sergeant Hassell Whitfield was among the temporary occupants of the Schilling family home.

The Schilling family grudgingly welcomed the arrival of the American liberators, having suffered already from the gunfire, tank rounds, and artillery that had laid waste to the homes of friends and neighbors. The G.I.s who crammed into the small shelter took quickly to the family, and especially to the Schilling's five-year-old son. In addition to Captain Brown and other key members of his staff, Staff Sergeant Hassell Whitfield was among the temporary occupants of the Schilling family home.

Throughout the night the Germans continued their assaults. Recalled Captain Brown, "When the Germans were not making a ground attack, they were bombarding us with artillery fire and direct fire attack." He further recalled two of his senior platoon sergeants advising him, "Captain, this is the roughest that we've ever experienced. I think we had better withdraw, if not we'll probably have to surrender."

While Captain Brown respected the advice of his NCOs and even agreed with their assessment, his orders were to hold and he was determined to follow those orders. When daylight came on January 17, Brown's Tough Ombres had survived the night, and the enemy attacks lifted. Of the nine counter-attacks during the period, only the last occurred during daylight. But when darkness came that evening, the enemy bombardment resumed.

This time German artillery seemed to have found their range, and the explosion of the big shells walked closer and closer to the Schilling home. The family huddled together in fear, an emotion no doubt felt by many of the young soldiers in and around the house, who still struggled to keep up a valiant and defiant face. But for the small Schilling boy, only five years old, the loud explosions and the undercurrent of fear and uncertainty, at last, became more than he could bear. Breaking away from his parents he ran out of the reverberating walls of the house and into the street where giant balls of fire and a deadly hail of white-hot shrapnel filled the air. With no thought for his own safety, Staff Sergeant Whitefield raced after the lad as the bombardment continued all around him. He was nearing the boy when both were struck down by a blast that sent shards of steel into soft flesh.

Captain Brown recalled,

"(Staff Sergeant Whitefield) asked someone to rub his arm, he claimed it hurt him. I did rub his arm, and he turned blue and died. The little boy died slowly in his mother's arms, and to see this, you read about these things, but to see the grief this mother was going through of her son being killed by something they had no control over, it really brings some strong lessons to you."

Staff Sergeant Hassell C. Whitefield was one of five members of the 90th Infantry Division who was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic actions in that deadly 36-hour battle for Oberwampach. The DSC was awarded to two of his comrades in Company A, 344th Field Artillery Battalion, as well as two men of the 359th Infantry Regiment. Like the great soldiers they were, four of these five earned the award for heroic offensive actions in fierce fighting against an equally aggressive enemy.

The citations for such awards usually speak of uncommon courage and aggressive resistance in the face of an armed enemy. Staff Sergeant Whitefield's award of the Distinguished Service Cross stands unique in the annals of military awards. Recalled Captain Brown, who witnessed the act and recommended Whitefield's award,

"He was a true hero. He gave his life trying not to defend his own life, but to rescue an innocent little boy, and truly he earned his decoration."

Sources:

A History of the 90th Division in World War II, The 90th Infantry Division, © 1946

Elson, Aaron, "A True Hero-Arnold Brown", Tank Books, © 2002

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED