Jack Lucas

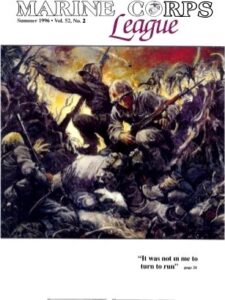

Reprinted - Marine Corps Magazine(Summer '96)

By William Standring

Fourteen and fresh from boot camp, Jacklyn Lucas was bound for glory.

One of the youngest Americans so far to win the Medal of Honor was a two-fisted, fire-plug of a kid who wanted so badly to fight he lied about his age to enlist, stowed away on a troopship to get into the war, and was at least technically AWOL when he got his shot at combat. He was, of course, a Marine and Private First-Class Jacklyn Harold Lucas, Company C, 1st Battalion, 26th Marines, 5th Marine Division.

Lucas’ story is as well begun as anywhere "during", to quote his citation, "action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, 20 February 1945."

As Lucas recalls, he’d come ashore at Red Beach with the third or fourth wave in a four-man fire team. They fought across the pork-chop-shaped island is the western waist and dug in for the night. Early the next afternoon, the commendation says, "while creeping through a treacherous twisting ravine which ran in close proximity to a fluid and uncertain front line on D- plus- I -day, PFC Lucas and three other men were suddenly ambushed by a hostile patrol which savagely attacked with rifle fire and grenades."

Quick to act when the lives of the small group were endangered by two grenades that landed directly in front of them, PFC Lucas unhesitatingly hurled himself over his comrades upon 1 grenade and pulled the other under him, absorbing. the whole blasting forces of the explosions in his own body in order to shield his companions from the concussion and murderous flying fragments. By his inspiring action and valiant spirit of self-sacrifice, he not only protected his comrades from certain injury or possible death but also enabled them to rout the Japanese patrol and continue the advance.

The broken, bloody, shrapnel-riddled soldier the stretcher-bearers hustled away had been 17 for less than a week.

A surgeon said, "he was too dam young and too damn tough to die." That was offshore aboard the hospital ship Samaritan when it began to look as if Lucas would live. Before the doctors were done, he'd go under the knife 22 times. There are still about 200 pieces of scrap iron in him, some the size of .22-caliber bullets. Lucas sets off airport metal detectors.

There was, in any case, no question he was young, and all the brig time he served for brawling suggests he was rugged. Lucas figures he was 5-foot-8 and 185 pounds when he enlisted at Norfolk, Virginia, on August 6, 1942; and he’d left Parris Islands to boot camp in Leatherneck fighting trim.

He turned pugnacious and "rambunctious" when he was 10, the year his father, a Plymouth, North Carolina, tobacco farmer died. "I was kind of shattered to lose my father," Lucas says, "I guess I just resented a lot of things and that loss. I was a mean kid."

His mother sent him off to Edwards Military Academy in Salemburg when he was 11, and, he says, "that good discipline kind of straightened me out." Lucas worked his way up to a cadet captain by the time he was 13, but his academy career almost ended that December when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. "That signed and sealed the thing for me right there," he says. "I was determined that I was going to serve in the Marine Corps and fight the enemy." Lucas left to sign up but he couldn’t fool the recruiters.

The next year, he was more artful. He told his mother he was going to sign her name on the enlistment consent papers. She could, he told her, try to stop him, but he’d find another way. She acquiesced on the promise Lucas would finish his schooling when he was discharged.

With his military school training, Lucas, 14, shone in basic. He did so well in Camp Lejeune's heavy machine-gun school that he was detailed to the training command. But that wasn’t what he had in mind. "My sole purpose," he says, "was to kill Japanese."

machine-gun school that he was detailed to the training command. But that wasn’t what he had in mind. "My sole purpose," he says, "was to kill Japanese."

When the rest of his unit was ordered to San Diego, ”I packed my seabag and got on the back of the train and stowed away to California." On the West Coast, a sergeant discovered Lucas had no records, but it was more trouble to send him back than to keep him. Shortly, Lucas was sailing with his battalion for a staging area in Hawaii.

So far, so good. But at Camp Catlin on Oahu, he made a mistake. In a letter to his 15-year-old sweetheart in Swan Corner, North Carolina, Lucas mentioned his age. A mail censor noticed, and Lucas was soon explaining things to his colonel. The CO decided he was too good a Marine to lose and Lucas said he’d just go join the Army anyway. When his unit shipped out for Tarawa, Lucas stayed in Honolulu.

He was determined to follow: "I was just obsessed to kill the Japanese." Marines who got into trouble tended to get sent to the front; Lucas started picking fights. "Anything I could provoke," he says. "I got locked up a number of times for fighting, but they let me go. But then I mashed up on some sergeant. I got two different tours of 30 days on bread and water and a lot of rock busting."

Celebrating his freedom after one stretch in the brig, Lucas and a buddy shanghaied a truckload of beer from ships stores and treated their company. The Marines worked their way through the iced brew, and Lucas and pal went back for a second load. "We were too inebriated to operate efficiently, and the police caught us," Lucas says. "These two M.P.s came and got me."

While one M.P. went for his buddy, Lucas says, "I beat the dickens out of the other guy. I had 18-inch biceps in those days. I was so muscled up 1 could run through a brick wall." In the process of running away, however, he got confused and ran back into the building in which he’d been caught, straight into the arms of the angry M.P.s.

Before he got out of the brig, Lucas said, "I figured this procedure isn’t working for me." He packed his gear, went to Pearl, caught a Higgins boat, and on January 9, 1945, climbed aboard one of the troopships Tokyo Rose said was bound for Iwo. As Providence would have it, cousin Samuel Oliver Lucas was aboard. With Samuel's help, Lucas hid in landing craft, slept on the weather deck, and fed himself for 29 days.

The day before his name would have moved from the AWOL to the deserter list, Lucas turned himself into Captain Robert H. Dunlap. The captain, who would win a Medal of Honor the same day as Lucas, took him to a Colonel Pollock. Lucas remembers the colonel said, "I’d like to have a whole shipload of fellows that want to fight as bad as you."

At Saipan, another Marine went ashore with appendicitis, and Lucas was issued his weapon and gear. On February 14, he turned 17 in the hold of USS Deuel, APA 160; there was no party. On February 19 he hit the beach at Iwo.

"Shells were flying, people were being blown apart, and bullets were everywhere," he says. "They made a hash of us. I was as anxious as ever to kill as many Japs as I could kill. It was just where I wanted to be."

On D-Day Plus One, Lucas and his team were making their way toward the Japanese airstrip on the plains northeast of Mount Suribachi. They had stopped to pound an enemy pillbox and had jumped for cover into one of two parallel trenches that led from it through the soft volcanic ash sand that covers the sulfurous island. To their surprise, the Marines discovered

"There were 11 of these Japs in this other trench. Eleven of them. We opened fire. There wasn’t time to put your weapon to your shoulder. We just fired off-hand."

"This last Jap I shot, I shot him in the forehead just above the eye. My rifle jammed. I was looking down at my rifle trying to get the damned thing unjammed, and when I did, I saw the grenades. I was the first to see them. I hollered grenades and I dove for them."

"I smashed my rifle butt against one and drove it into the volcanic ash, and fell on it, and pulled the other one under me. I was there to fight, and we were there to win. What you have to do you do to win. It was not in me to turn to run."

"That volcanic ash and the good Lord saved me. If I’d been on hard ground that thing would have split me in two. There was just one explosion. One was all I could handle, and I had trouble handling that one. It blew me over on my back, and it punctured my right lung, but it never knocked me out." Lucas also sustained injuries to his thigh, neck, chin, and head."

The rest of the team sprinted down the trench, turned, and fired down the other. Lucas lay on his back, his right arm twisted so far underneath him he thought it had been blown off. His mouth and throat filled with blood, and he might have drowned if he had lost consciousness. He kept moving his left hand to show that he was alive. "That was the only thing I could move", he says. A Marine from another unit came up and Lucas, barely recognizable as an American, was afraid he would be shot, but the soldier called for a Corpsman.

While the medic worked on him, a Japanese soldier popped up from a hole in the trench. The Corpsman shot him. A mortar barrage walked up to the edge of the trench and delayed the stretcher-bearers. As they hurried off, one stumbled and dropped his end. Lucas split his head open on a rock. "I looked up at him and smiled to let him know 1 knew that what he was trying to do, and I appreciated it. I could see he was exhausted."

On the evacuation beach, a Corpsman covered Lucas with a poncho for shelter from the elements. "I thought, Oh, Lord, I’m dead," he says. "Of course, that morphine took hold, and I passed out."

As sailors hoisted Lucas aboard an LST, they nearly dropped him into the sea. Someone caught him by the foot. He lay in the hold with hundreds of other wounded until there was room for him on the Samaritan. Before it sailed for Honolulu, the flag went up on Suribachi. The word was passed on the ship. "I felt as jubilant as I could be," Lucas says. "I’d fought for my country. I felt a great deal of pride in that. The only regret for me was that I didn’t get to stay there longer to kill more of them."

In seven months, Lucas was in good enough shape to be separated. When he was put up for the Medal of Honor, the Corps tried to delay his discharge, but Lucas was having none of it. "I didn’t even know what the Medal of Honor was," he says. "I didn’t think about any medals going into battle. I went there to do one thing, and that was to kill the Japanese. I didn’t want no medals."

He was visiting friends in North Carolina when the White House summoned him to Washington to  accept the award from Harry S Truman on October 5, 1945. There were 14 other recipients that day, all sailors and Marines, among them Pappy Boyington. Among the onlookers were Generals George Marshall, George Patton, and Hap Arnold, Admiral Nimitz, and Secretary of Defense James Forrestal. Marshall sat next to Lucas’ mother. She’s 92 now and lives with him in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

accept the award from Harry S Truman on October 5, 1945. There were 14 other recipients that day, all sailors and Marines, among them Pappy Boyington. Among the onlookers were Generals George Marshall, George Patton, and Hap Arnold, Admiral Nimitz, and Secretary of Defense James Forrestal. Marshall sat next to Lucas’ mother. She’s 92 now and lives with him in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

"Truman said he’d rather be a Medal of Honor winner than President of the United States," Lucas says. "I said, sir, I'll swap with you"

There was a Nimitz Day parade afterward in Washington and another three days later in New York. "I had my own car, and I’d stand up, and women would throw kisses at me," Lucas says, "and some of them ran out between the barricades and I got voluptuous kisses. I was 17-years-old, and I had a helluva time."

Time, of course, moves on. In the years that followed, Lucas, true to his word to his mother, finished high school and graduated from college. He got married in dress blues on the television show "Bride and Groom" in 1952. It was the first of three marriages, none of them successful. He has four sons, one a West Pointer, a daughter, and seven grandchildren.

His second wife tried to hire an undercover state trooper to kill him. Lucas helped her win leniency from the court. "I’m still friends with all of them," he says, "even the one who tried to kill me."

During Vietnam, Lucas accepted a commission in the Army but found his methods and the military still didn’t mix. He got out after six years. He has made and lost a fair amount of money in the meat business, had IRS troubles, and lived temporarily in a tent on a friend's Maryland farm.

"Life is not just a bed of roses; it can be like a roller coaster ride," Lucas says. "I’ve lived the life of probably two or three men in many ways." In 1985 he returned to Iwo. "I had to try to walk on the beach without having to duck. I had time to see more of that island than I had time to walk around and observe before," Lucas says. "I could not get to the place where I was wounded. But I could see from the top of Mount Suribachi approximately where I was wounded. That’s when the feeling came back, a good feeling, that we had whipped their butts."

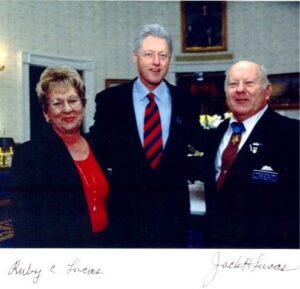

He’s also gone back to Washington. You may have seen part of his visit on television. In January 1995 the White House invited Lucas, his son the West Pointer, and grandson to be President Clinton's guests at the State of the Union Address. The theme of the speech was service to the country, and Mrs. Clinton thought the Lucas family was a good example.

Lucas visited the Clintons before the speech and chatted.

Lucas visited the Clintons before the speech and chatted.

"I told her, I said, you are a magnificent looking lady. You look a whole lot prettier in person than you do on television."

"One of the things I told him is, sir; you know, you’ve got a lot of courage. If I was on a job and somebody criticized me as much as they criticize you, I’d be in the nuthouse."

That night, at the end of the speech in the well of the House of Representatives, the President paused to recognize Lucas sitting in the balcony next to the First Lady.

"They saved me as the last one to be introduced," Lucas says, "but, man, was I ever the one to get the ovation. He started telling about me, and all the congressmen and senators looked up in the gallery at me, and then they clapped for five minutes. It swept me away."

"I got so choked up, I couldn’t even smile. Honest to goodness, I had to swallow a hundred times to keep the tears from running down my face. I thought, gosh, here is the son of a tobacco farmer, and all these people and mom was down here in Mississippi watching me on TV."