James H. Howard

A World At War

Found: The Horatius at the Oschersleben Bridge Bombers Hail One-Man Air ForceBy Andrew A. RooneyStars & Stripes Staff Writer

A MUSTANG BASE, Jan. 18-- A lone and unidentified Mustang pilot battled 30 German fighter planes for half an hour high over central Germany last Tuesday. Fortress crewmen who cheered as they watched the U.S. fighter send plane after plane smoking to the ground have been trying ever since to find out the pilot's identity.

A MUSTANG BASE, Jan. 18-- A lone and unidentified Mustang pilot battled 30 German fighter planes for half an hour high over central Germany last Tuesday. Fortress crewmen who cheered as they watched the U.S. fighter send plane after plane smoking to the ground have been trying ever since to find out the pilot's identity.

With his deeds buried in an over-cautious intelligence report, Fighter Command officials had to comb the records to find the man for whom bomber crews were claiming six destroyed enemy planes and countless bombers saved. With the records, they dug up possibly, the best fighter pilot story of the war.

Today the fighter pilot those men watched wage the story-book battle in their defense finally was identified.

He is Squadron Leader....

Spring, 1941: A World at WAR!

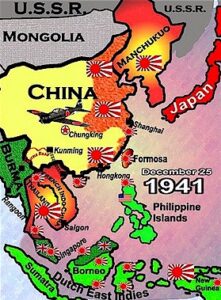

EUROPE: Germany invades Yugoslavia forcing its surrender. Nazi troops occupy Paris, Poland, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Romania, Czechoslovakia, as well as most of northern and central Europe.

MEDITERRANEAN: Greece, which was invaded by Italy the previous years, surrenders after the arrival of Nazi forces. The combined German/Italian Axis have gained control of most of the region.

NORTH AFRICA: Field Marshall Erwin Rommel arrives to attack Tobruk amid Italy's efforts to control Egypt and the Suez Canal.

MIDDLE EAST: A pro-Axis government is set up in Iraq.

ASIA: Japanese Forces control Manchuria and most of eastern China, including the major ports at Shanghai and Hong Kong. After striking a deal with the Vichy French their troops also occupy French Indo-China and Thailand (Siam), giving them control of nearly all of the eastern coastline of Asia.

BRITAIN: After surviving the deadly Battle of Britain the previous year, British citizens continue to try to rebuild amid renewed Luftwaffe bombing of their Island Nation as they stand alone now, against the Nazi juggernaut.

OCEAN: German submarines (U-Boats) rule the waters from the North Sea to the eastern American coastline.

UNITED STATES: Congress passes the $50 Billion Lend-Lease Act giving President Roosevelt the power to sell, transfer, exchange, and/or lend equipment to any country to help it defend itself against the Axis powers. Meanwhile, most American's seek to distance themselves from the rest of the world at war in hopes that the United States can remain neutral.

DIEGO, CALIFORNIA: When Lieutenant Commander Wade McCluskey called together the pilots of VF-6 in the spring of 1941 the entire event was shrouded in mystery. After the aviators of the Navy's Fighting Sixth had been assembled the door was locked and every man in the room was sworn to secrecy. Moments later a distinguished gentleman in civilian attire introduced himself as Commander Rutledge Irvine, U.S. Navy (Retired).

Commander Irvine began by assuring the assembled pilots that his mission to San Diego had been approved by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, but that every word spoken in the clandestine meeting must be held in the utmost secrecy. What he was about to propose was not just an opportunity to participate in a highly classified mission; what was taking place behind locked doors that day might well, if it became known, create a volatile international incident that could propel the United States into the very war it had struggled for years to avoid.

For nearly a year a small number of Americans had been involved in that war after secret recruiting efforts to enlist aviators to aid Britain's RAF and the Canadian RCAF. These young men, citizens of the United States, traded in their U.S. Army Air Corps wings to join a foreign air force in its valiant defense against the imposing German Luftwaffe. Some became part of the three legendary Eagle Squadrons, others were simply absorbed into various RAF or RCAF units. All were American airmen without sanction, voluntarily defending a foreign nation against a nearly invincible aggressor.

If the young pilots of VF-6 were aware of earlier clandestine recruitment of aviators for the Eagle Squadrons and suspected something similar was about to happen, they would have been only partially correct. Instead of speaking of the valiant battle to save Britain from Hitler's blitzkrieg in Europe, Commander Irvine focused upon an equally though lesser publicized threat to the world, the escalating spread of the Imperial Japanese empire in Asia. China had been at war with Japan for four years, during which the Chinese military had been pushed back 800 miles into the interior. With their seaports now occupied, the government under Chiang Kai-shek had been isolated and was near collapse for lack of a lifeline. The recently authorized Lend-Lease Act had been passed not only to enable the United States to provide assistance to England without violating its neutrality but also to enable the Chinese to defend themselves against the swift and brutal advance of Japan.

"President Roosevelt," Commander Irvine told the young Navy pilots, "is intent on furnishing some kind of military assistance to China so that she can survive. I am here to offer all pilots of VF-6 who are reserve officers the opportunity to resign from your service and join a volunteer organization in the Far East to defend the Burma Road against Japanese bombing attacks."

When Irvine had finished his presentation, he handed out application forms. Many of the pilots of VF-6 wasted little time discarding them amid comments that this was a foolish, and dangerous, waste of one's military career. Others, intrigued by the potential for adventure in a foreign land or motivated by the unusually high salary of $600 - $700 per month, gave the matter more serious consideration.

Twenty-four-year-old Ensign James H. Howard of St. Louis recalled, "I couldn't have been in a better position at a better time. The nostalgia of going to China would be a strong incentive, but the overpowering reason was my yearning for adventure and action. It didn't take me long to decide to sign up."

On September 1, 1939, with an eye to expanding his burgeoning German empire, Adolph Hitler sent his troops into Poland. Two days later France and England declared war and thus, believe many historians, began World War II. It is a precept that ignores the birth of that war that began, not in Europe in 1939, but in Asia eight years earlier. In fact, World War II may have been born one full year before Adolph Hitler's rise to power in Germany.

War in Asia

By 1931 the island nation of Japan, struggling to pull itself out of a great depression that had overtaken the country in 1929, had invested heavily in the rich resources of the nearby Chinese province of Manchuria (Manchukuo). With a burgeoning population and limited territory, the Japanese army launched an imperialist conquest, seemingly the only hope for Japan's future. After seizing Manchuria in 1931, the following year Japanese forces attacked Shanghai and gained control of much of China's coastal area.

By 1931 the island nation of Japan, struggling to pull itself out of a great depression that had overtaken the country in 1929, had invested heavily in the rich resources of the nearby Chinese province of Manchuria (Manchukuo). With a burgeoning population and limited territory, the Japanese army launched an imperialist conquest, seemingly the only hope for Japan's future. After seizing Manchuria in 1931, the following year Japanese forces attacked Shanghai and gained control of much of China's coastal area.

For centuries China had been its own worst enemy, struggling through internal strife and tribal warfare. Indeed, in 1900 the United States joined a large international alliance in military actions to quell an uprising of the I-Ho Ch'uan, better known as The Boxers. The large Asian nation achieved some unity when Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek became head of the Nationalist Party in Nanjing (Nanking) in 1928. Almost immediately he became faced with a war on two fronts: continued internal strife as he ruled a loose coalition of corrupt and power-hungry Chinese warlords, and the threat of the Japanese advance.

Chiang Kai-Shek's worst nightmares for the future of China came true in 1937. Outside the walled city of Wanping stood China's oldest bridge, the Marco Polo Bridge. On July 7 the commander of Japanese forces holding the east edge of the bridge notified officials at Wanping that one of his soldiers was missing and believed to be inside the walled city. His demand to cross the bridge and enter Wanping was met by 1,000 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Soldiers.) That night the Japanese shelled the city, then crossed the bridge with the dawn. It was arguably the first battle of World War II.

The incident at the Marco Polo Bridge launched Japan's all-out offensive to control China. In the months that followed that opening volley, the Emperor's soldiers breached China's Great Wall and continued to quickly seize all of northeastern China amid the bold proclamation that Japan would annex China within three months. On August 14 the air war began with an ill-fated attempt by Chinese bombers to attack the Japanese flagship Idzumo, at anchor near Shanghai. Errant bombs dropped on the city, killing more than 1,200 citizens in what became known as Bloody Saturday. Twelve Japanese bi-plane bombers responded by attacking Hangzhou. The Chinese Air Force, commanded now by a former American fighter pilot, responded by shooting down eleven of them.

The incident at the Marco Polo Bridge launched Japan's all-out offensive to control China. In the months that followed that opening volley, the Emperor's soldiers breached China's Great Wall and continued to quickly seize all of northeastern China amid the bold proclamation that Japan would annex China within three months. On August 14 the air war began with an ill-fated attempt by Chinese bombers to attack the Japanese flagship Idzumo, at anchor near Shanghai. Errant bombs dropped on the city, killing more than 1,200 citizens in what became known as Bloody Saturday. Twelve Japanese bi-plane bombers responded by attacking Hangzhou. The Chinese Air Force, commanded now by a former American fighter pilot, responded by shooting down eleven of them.

In the weeks that followed Japanese bombers based out of Taiwan unleashed their fury on Shanghai and Nanjing. With limited air assets, China's defense was poised precariously close to utter defeat. On August 20 Chinese ground forces fought to turn back another wave of bombing attacks when one of their anti-aircraft shells errantly fell in the harbor and struck the USS Augusta, killing one American and wounding several other sailors. They were, perhaps, the first American casualties of World War II.

The Nippon juggernaut continued in a war the United States tried, but couldn't ignore. On December 12 Japanese warplanes repeatedly attacked the USS Panay which was patrolling the Yangtze River near Nanking. Two American sailors were killed, eleven wounded, and the Panay was ordered abandoned. Even as the survivors struggled to reach the shore Japanese pilots strafed the waters and the shoreline. It might well have been the incident to propel the United States into war with Japan four years before Pearl Harbor, but most Americans though outraged accepted Japan's apology along with the excuse that its pilots had not seen the American flag flying from the U.S. gunboat. The Japanese paid an indemnity for their mistake and the American public responded with a collective sigh of relief that war had been avoided. A Gallup Poll that followed two weeks into the new year indicated that Americans overwhelmingly (70%) favored a complete withdrawal of all-American ships, Marines, missionaries, and medical missions to China.

Ignored by the rest of the world and left alone to resist Japan's continued bombardment and fierce ground attacks, Chiang Kai-Shek withdrew from Nanjing and established his Capitol at Hankow. The months that followed the December 1937 fall of Nanjing, though little remembered in the West, was one of the most tragic periods in human history. In the vicious, brutal retribution heaped upon the Chinese people in the Japanese Army's Rape of Nanking, Nippon soldiers beheaded so many men, women, and children that their arms became sore. It was estimated that from December 1938 to March 1939, 369,000 Chinese civilians and Prisoners of War were beheaded, burned, buried alive, disemboweled, or used for bayonet practice. As many as 80,000 Chinese women and girls were raped, and most of them were subsequently mutilated and then murdered. Nine months after the fall of Nanjing the advancing Japanese seized control of Hankow, and Chiang Kai-Shek withdrew even further inland, establishing the capital at Chungking.

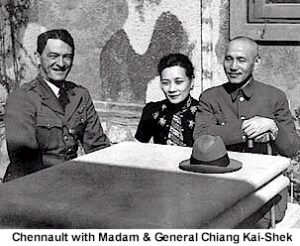

One American who refused to ignore the plight of the Chinese people and their embattled government in those dark days before war engulfed the rest of the world was a chisel-faced, thirty-eight-year-old, former fighter pilot. Claire Chennault had earned his wings in the post-World War I Army Air Corps and, though he had never flown combat, developed a unique ability for understanding pursuit (fighter) aviation. His propensity for pursuit over bombardment placed him at odds with conventional Air Corps doctrine in the early 1930s. His direct and often abrasive personality further alienated him from many of the developing leaders in U.S. Army aviation. His discouragement with the perceived short-sightedness of his commanders and most fellow pilots in regard to developing advanced pursuit aircraft and combat tactics, combined with a hearing loss, lead to his early retirement in 1937. Even as he was relocating his family back to his native Louisiana, in far-away China his name was being bandied about to assume command of Chiang Kai-Shek's fledgling Air Force.

One American who refused to ignore the plight of the Chinese people and their embattled government in those dark days before war engulfed the rest of the world was a chisel-faced, thirty-eight-year-old, former fighter pilot. Claire Chennault had earned his wings in the post-World War I Army Air Corps and, though he had never flown combat, developed a unique ability for understanding pursuit (fighter) aviation. His propensity for pursuit over bombardment placed him at odds with conventional Air Corps doctrine in the early 1930s. His direct and often abrasive personality further alienated him from many of the developing leaders in U.S. Army aviation. His discouragement with the perceived short-sightedness of his commanders and most fellow pilots in regard to developing advanced pursuit aircraft and combat tactics, combined with a hearing loss, lead to his early retirement in 1937. Even as he was relocating his family back to his native Louisiana, in far-away China his name was being bandied about to assume command of Chiang Kai-Shek's fledgling Air Force.

Chiang Kai-Shek had seen aviation as a critical means of defense for his large nation shortly after coming to power. His foresight was reinforced when Manchuria quickly fell to Japanese aggression in 1931, and he promptly sought help from Britain to build a Chinese Air Force. With colonies of its own in India, Burma, and elsewhere in Asia and the Pacific, Britain declined to get involved for fear of antagonizing Japan. In 1932 the United States sent nine experienced pilots under retired Air Corps Colonel John Jouett in an unofficial mission to build a Chinese air force. The Japanese government responded with a diplomatic outcry. Their demands and threats directed towards Washington, D.C. sent Jouett home in 1934, but not before he and his nine American companions had fashioned from virtually nothing, a viable Chinese Air Force with 250 fighters and 350 American-trained pilots.

In the two years that followed Jouett's departure, the Chinese Air Force fell into great disrepair amid lax discipline, deadly air crashes, and a mish-mash of mercenaries from various nations who had been hired to fill the leadership void left by the American airman's departure. Early in 1937, in an effort to boost morale and to demonstrate how important he felt his meager air force was, the Generalissimo appointed his popular wife, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, to be Secretary-General of the Chinese Air Force. One of her first official acts was to launch an international search for a new commander, a search which eventually led to Louisiana and an under-appreciated American fighter pilot facing early retirement.

"At midnight on April 30, 1937,'' wrote Chennault in his autobiography, "I officially retired from the U.S. Army with the rank of Captain. On the morning of May 1, I was on my way to San Francisco, China bound.''

Claire Chennault's agreement brought him to China as a civilian advisor to the Chinese Air Force (CAF), a job slated to pay him $1,000 for each of the three months he had agreed to in his service contract. What was initially little more than a good-paying three-month job would ultimately become a lifetime love affair. Six weeks into that new job Chennault was touring China's small and scattered airfields when the fighting began at the Marco Polo Bridge. Almost immediately China's air defense against the veteran Japanese Air Force became the sole responsibility of a retired American fighter pilot who couldn't speak a word of Chinese.

Claire Chennault's agreement brought him to China as a civilian advisor to the Chinese Air Force (CAF), a job slated to pay him $1,000 for each of the three months he had agreed to in his service contract. What was initially little more than a good-paying three-month job would ultimately become a lifetime love affair. Six weeks into that new job Chennault was touring China's small and scattered airfields when the fighting began at the Marco Polo Bridge. Almost immediately China's air defense against the veteran Japanese Air Force became the sole responsibility of a retired American fighter pilot who couldn't speak a word of Chinese.

The job facing Chennault was an impossible one for many reasons. By 1937 China's Air Force consisted of a small and patch-work inventory including only ten Curtiss P-26 fighters, six German-built Henkle bombers, six Savoia-Marchetti's, nine Martin B-10s, and about 100 Curtiss Hawk bi-plane fighters. By contrast, Japan had available in the region at least 2,000 fighters and bombers to throw against the cities of China.

Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek placed their confidence in Chennault and called him to Nanjing on September 1 to take command of the city's defense against continued enemy bombardment. When the Capitol city fell in December Chennault, now well beyond the term of his initial contract, remained in China to follow them to Hankow. By the time Hangkow fell and the seat of government moved to Chungking, China had been isolated from the outside world by an enemy that controlled most of its eastern coastline, virtually all of its vital ports, nearly all of its railways, and half of its landmass.

The Burma Road

Though Japan failed to fulfill its goal of annexing China within three months following the 1937 battle at Marco Polo Bridge, by the summer of 1938 China was badly beaten, though not defeated. With its military forces over-extended and suffering from heavy casualties, Japan scaled back its ground assault at the end of 1938, content to occupy China's coast and port cities. For the land-locked government of Chiang Kai-Shek survival was a matter of time. The only route of supply into China was through Haiphong Harbor and then by rail from Hanoi to Kunming. The future of that route was tenuous at best.

Though Japan failed to fulfill its goal of annexing China within three months following the 1937 battle at Marco Polo Bridge, by the summer of 1938 China was badly beaten, though not defeated. With its military forces over-extended and suffering from heavy casualties, Japan scaled back its ground assault at the end of 1938, content to occupy China's coast and port cities. For the land-locked government of Chiang Kai-Shek survival was a matter of time. The only route of supply into China was through Haiphong Harbor and then by rail from Hanoi to Kunming. The future of that route was tenuous at best.

The Chinese people responded in a manner that would have made their ancestors proud. Seven hundred miles from Kunming was the railhead at the border town of Lashio in the British colony of Burma. Connecting the two cities was a small trail that had served as a trade route for centuries. As early as 1937 Chiang Kai-Shek realized that if that trail could be turned into a highway, essential supplies and war materials could be shipped by other nations to the Burmese port at Rangoon, freighted to Lashio, and then transported by truck to Kunming. China lacked the equipment and technology to build such a road under the best of conditions, however. The road the Generalissimo now called on his people to construct would have to be built across the Yunnan Province, which comprised some of the highest mountains and deepest canyons in the world.

What the Chinese people lacked in equipment and technology they made up for in sheer numbers and determination. By the thousands they streamed into Yunnan Province in the summer of 1937, bringing their ancient tools to clear jungles, oxen to drag hand-hewn rock, and even their children to build a highway through canyons, along rocky escarpments, and over high mountains. Construction continued through the cold winter amid not only physical hardship but the demoralizing news that Nanjing and Shanghai had fallen to the enemy. For sixteen months more than 100,000 Chinese labored on. Thousands died, some in accidents, many more from malaria that pervaded the jungle, and others beneath the guns of attacking Japanese fighter planes.

Author Russell Whelan (The Flying Tigers) wrote: "They removed the debris of the cliff sides with handmade baskets. They smoothed the road with stone rollers which they carved out of rock and hitched to bullocks; or, lacking bullocks, to a train of their own bodies. They worked and they died at their work by the uncounted thousands, through the raw winter and the searing heat of summer, through landslides, floods, and plague. They dug two thousand culverts and built three hundred bridges, including two suspension bridges across the gorges. For seven hundred and twenty-six miles they cut a level strip from nine to twenty feet in width across the rocky face of Asia. They built the most dramatic, the most important highway, in the history of the world.

Author Russell Whelan (The Flying Tigers) wrote: "They removed the debris of the cliff sides with handmade baskets. They smoothed the road with stone rollers which they carved out of rock and hitched to bullocks; or, lacking bullocks, to a train of their own bodies. They worked and they died at their work by the uncounted thousands, through the raw winter and the searing heat of summer, through landslides, floods, and plague. They dug two thousand culverts and built three hundred bridges, including two suspension bridges across the gorges. For seven hundred and twenty-six miles they cut a level strip from nine to twenty feet in width across the rocky face of Asia. They built the most dramatic, the most important highway, in the history of the world.

"They built the Burma road."

Their accomplishment in at last completing the Burma Road, though seldom viewed in its true capacity of dedication and endurance, was comparable to the Great Wall built by their ancestors two millenniums earlier. Viewing the Chinese people's amazing accomplishment, one American engineer remarked,

"My God, they scratched this thing out of the mountains with their finger-nails."

By 1939 a slow trickle of supplies, shipped first to Rangoon, then freighted to Lashio, were making the slow, winding trek into China via this new lifeline. Though the rail line into Hanoi continued to be the principal route of supply into China, completion of the Burma Road gave the Chinese people both a sense of accomplishment and an alternative if the Indo-China pipeline ever closed.

By 1939 a slow trickle of supplies, shipped first to Rangoon, then freighted to Lashio, were making the slow, winding trek into China via this new lifeline. Though the rail line into Hanoi continued to be the principal route of supply into China, completion of the Burma Road gave the Chinese people both a sense of accomplishment and an alternative if the Indo-China pipeline ever closed.

The Japanese dared not attack the rail line in the French colony, so instead, they began the near-daily bombing of the road out of Burma. With continued determination, as quickly as the enemy bombers disappeared, the volunteer Chinese workforce appeared out of the mountains and jungles to promptly repair their lifeline. "Let them (bombers) come," the valiant Chinese stated. "It costs the Japanese a thousand dollars every time they drop a bomb on the road. Even when they hit it, we can fill up the holes for only a few cents' worth of labor. So, if they bomb it often enough, Japan will soon be broke."

On September 1, 1939, the face of the building worldwide conflict fully emerged when Hitler invaded Poland, forcing Britain and France to declare war on Germany within 48-hours. In Washington, D.C. the Congress amended the Neutrality Act of 1935 in effort to maintain trade with the warring parties without taking sides in the conflict. The new language of this legislation provided for the United States to trade with the warring nations only on a "cash-and-carry" basis, and prohibited U.S. vessels from combat zones. The language was designed primarily to avoid a confrontation with Germany, and ironically, did not apply to the situation in Asia--Japan had conducted its aggression towards China without ever declaring a state of war.

On June 14, 1940, Nazi troops marched into Paris and Hitler established the pro-Axis Vichy government to manage the affairs of southern France and its worldwide colonies. Almost immediately the Luftwaffe unleashed its aerial might on London in the Battle of Britain. In many ways the war in Europe mirrored the undeclared war that had been going on in Asia for years:

• In Europe, England stood alone against Germany while in Asia, China stood alone against Japan.

• Germany sought to bring England to its knees with the unrelenting bombing of her cities in a campaign that killed thousands and leveled entire neighborhoods. In China, this bombardment had been underway for three years, killing thousands and destroying countless neighborhoods in the Capitol at Chungking and elsewhere.

• In England the people of the Island Nation rallied valiantly during their darkest hours under the leadership of Winston Churchill to emerge beaten but unbroken. In China, the isolated government under Chiang Kai-Shek rallied the citizens to unprecedented determination to survive a daily onslaught.

In the diplomatic war of that period, Japan brought pressure to bear on England to close the Burma Road leading out of their Asian colony. Fully occupied resisting one enemy, Britain dared not create a new enemy in the Far East where it had extensive holdings, and thereby open a two-front war. Ultimately, Germany's bombing of London during the Battle of Britain indirectly did what the Japanese bombings in Asia could not--and the Burma Road was ordered closed.

On September 27, 1940, Germany, Italy, and Japan united as allies in their quest for world domination when they signed the Tripartite Act. This signaled the death-knell of the last of China's two lifelines. Under pressure from Japan, French Indo-China closed the railway from Hanoi to Kunming. It was the very situation Chiang Kai-Shek had feared, the potential threat that had prompted him to order the construction of the Burma Road in 1937. Chinese author/philosopher Lin Yu-Tang had noted the road's importance by stating, "The Burma Road is China's jugular vein." By the fall of 1940, Japan had effectively severed China's jugular vein, leaving an ancient civilization to slowly bleed to death.

Great Britain emerged from the devastating bombings of July - October 1940 unbroken and victorious largely because of the valor of its Royal Air Force. Winston Churchill noted the key role of these fliers in his speech to the House of Commons when he said, "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few." By contrast, at the time the British Prime Minister bestowed such praise on his airmen, little remained in Asia of China's Air Force. The Chinese people continued to survive not because of a valiant defense, but due to a determined spirit and an early-warning system developed and refined by Claire Chennault. That rudimentary but vast and effective spider-web quickly relayed notice of enemy air missions, noting the source, direction, number, and type of enemy bombers and/or fighters. It allowed the Chinese people time to seek shelter, though even that was often not enough and they died by the thousands as their cities were ravaged from above.

Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-Shek set in motion his own diplomatic corps in the United States. China had not only gained some powerful friends in Washington, D.C. but benefited from the American President's understanding of the danger posed by continued Japanese expansion in Asia and the Pacific. Franklin Roosevelt successfully convinced Winston Churchill that, despite the danger of angering Tokyo, it was in the best interest of both the United States and Great Britain to restore the flow of blood through the jugular vein of China. After three of the darkest months in China's long history, at last, the Burma Road was re-opened.

That action served, however, as little more than a band-aid in the gaping wound to China's figurative neck. The now-closed railway through Hanoi had once transported an average of forty-thousand tons of supply to Kunming each month. Through the winter of 1940-41, the Burma Road's capacity for re-supply was only one-tenth of that amount. The route was harsh, winding, and perilous, even without the renewed bombardment by Japanese aircraft--bombardment the CAF lacked the planes or pilots to combat.

Claire Chennault was a man of action who, despite his great potential, was ill-adept at diplomacy and prone to alienate those who held the reins of power. (The exception to this was Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, for whom he worked and with whom he shared mutual respect and lifetime friendship.) For this reason, his accomplishments in the Winter of 1940-41 may be the best illustration of his true greatness, rising above his personal character flaws to achieve through diplomacy one of the most unorthodox solutions to the life of China that might have been imagined. With the blessings of his Chinese employers, he traveled to Washington, D.C. to propose a secret plan to build an air force to defend the Burma Road--an air force of American fighter planes, flown by volunteer American pilots.

The A.V.G.

Claire Chennault's plan for an American Volunteer Group (A.V.G.) required three components: Permission, Planes, and Pilots. The first of these would prove to be the most difficult amid firm opposition from Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, Army Air Chief General Hap Arnold, and Rear Admiral Jack Towers, the Navy's Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Chennault's plan skirted the limits of the Neutrality Act at best; it certainly denied the United States any viable claim to non-belligerence. Chinese diplomats and businessmen continued their efforts to sell the idea to America's military leaders while Chennault, determined to win the battle at home, went to work on the task of finding fighters with which to fight the war in China.

At the Curtiss-Wright Airplane Company Chennault found 100 crated but unwanted P-40Bs. The French government had ordered these for their own defense before the fall of Paris halted the sale. Desperate for any aircraft, the RAF had agreed to purchase these fighters despite the fact that they were older model fighters that were not equipped with a gun sight, bomb rack, or provisions for attaching auxiliary fuel tanks to the wing or belly. Burdette Wright, vice president of Curtiss-Wright and a long-time friend of Chennault's, offered to install a new assembly line in the plant to turn out newer models P-40s for the British if they would, in turn, give up their claim to the crated P-40Bs. It was an offer the British quickly accepted. When President Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease Act on March 11, 1941, it opened the way for China to purchase these 100 fighters with four Lend-Lease loans totaling $150,000,000.

Permission came the following month when, over the objections of his military commanders, President Roosevelt embraced the unorthodox idea of sending former U.S. military pilots to defend China. Most accounts of the A.V.G. allude to an April 15 secret Executive Order issued by the President, though no evidence has since emerged that indeed such a published document existed. It is far more likely that this was an informal Presidential action, authorizing the clandestine recruitment of pilots and ground crews from the ranks of U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps Aviation, each of whom would voluntarily resign from their respective branches of the U.S. Military and sign a one-year contract of service in China. The Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO) based in Lowing was designated as China's agent in the process of both deliveries of the 100 P-40s and in recruiting 100 American pilots and 200 ground-crewman to man and maintain them. William Pawley, son of a rich American family and part-owner in CAMCO, set up an office in New York to coordinate everything from recruitment to issuing contracts.

Initially, Claire Chennault personally began the recruitment effort, visiting Army airfields and Naval training stations in May and June. Similar secret efforts had been initiated the previous year by the Knight Commission in clandestine efforts to recruit American airmen for service in the RAF and RCAF, but Chennault's efforts were quite different. Service in the RAF/RCAF offered would-be airmen who had washed out of pilot training in the United States, or who had been rejected for minor medical conditions or lack of the requisite college education, a second chance to fly. Claire Chennault's A.V.G. would be facing the large and combat-experienced pilots of the Japanese air force with a meager force of 100 obsolete fighters. Chennault would accept only pilots between the ages of 22 to 28, pilots with a minimum of 2-years of U.S. Army or Navy aviation training and experience, and men who had adapted themselves to the process of military discipline and personal leadership. He wanted adventurers but not renegades; he looked for men who were in sense soldiers of fortune, but who were motivated by more than money. (The men enlisted for service in Europe by the Knight Commission received the same salary as their RAF/RCAF counterparts. The unique nature of CAMCO's contract offered pilots of the A.V.G. a $600 - $750 per month salary, and salaries for ground crews, though less, were still considerable.)

In his spiel to prospective recruits, Claire Chennault pulled no punches, nor did he hide the details. The CAMCO contracts would list all volunteers as civilians employed to serve in China as instructors, or in Lowing's CAMCO factory in the manufacture, repair, and operation of airplanes. They would travel to China on Dutch ships under visas listing them as anything other than what they would truly be--hand-picked fighter pilots from the United States of America. He also did not hide from them the fact that they would be outnumbered, out-gunned, and facing a formidable veteran enemy air force. He talked of the plight of the Chinese people, shared the history and importance of the Burma Road, and insured would-be volunteers that in helping China they would be indirectly serving in the best interests of their own country. Upon completion of an A.V.G. volunteer's contract, the volunteers would be authorized under Roosevelt's secret Executive Order to return to their branch of service without loss of rank. In the event the United States entered the war, A.V.G. personnel would be entitled to terminate their contract and return to the service of their own country.

After initiating this recruitment process, Chennault went back to China in the late Spring, leaving the task of continuing the interview and selection process of experienced aviators he trusted. Thus, it was that Commander Rutledge Irvine found himself in San Diego accepting a completed application from Navy Ensign James H. Howard.

James H. Howard

James Howell Howard, Naval aviator, and U.S. Army Air Force ace were born in Canton, China, on April 8, 1913. His family came to China in 1910 on a medical mission to the Canton Christian College, which was sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania. Howard's father was a physician who, for seventeen years, served the needs of the people of China. Except for two furlough periods, James Howard saw little of his own country until the family returned to the United States to settle in St. Louis in 1917. For fourteen-year-old James Howard, the return home was a welcome but sometimes difficult readjustment. Because of his foreign birth, he was known throughout his high school years at John Burrough's School in St. Louis as "China." His only comfort was the reassurances of his father that because his parents were American Citizens serving abroad at the time of his birth, their son was also an American Citizen. Still, the nickname continued to follow him.

James Howell Howard, Naval aviator, and U.S. Army Air Force ace were born in Canton, China, on April 8, 1913. His family came to China in 1910 on a medical mission to the Canton Christian College, which was sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania. Howard's father was a physician who, for seventeen years, served the needs of the people of China. Except for two furlough periods, James Howard saw little of his own country until the family returned to the United States to settle in St. Louis in 1917. For fourteen-year-old James Howard, the return home was a welcome but sometimes difficult readjustment. Because of his foreign birth, he was known throughout his high school years at John Burrough's School in St. Louis as "China." His only comfort was the reassurances of his father that because his parents were American Citizens serving abroad at the time of his birth, their son was also an American Citizen. Still, the nickname continued to follow him.

During World War I while young Howard was attending classes, his father served as a medical officer to the U.S. Army Aviation Service. After finishing high school James Howard relocated to Southern California to attend Pomona College and prepare for a future that his family believed would take him in his father's footsteps in medicine. Instead, during his senior year, young Howard's thirst for adventure was stimulated during a visit to the campus but a recruiter for U.S. Naval aviation. He submitted an application, completed the physical examination, and reported to Long Beach shortly after graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree, to begin the long process of earning his wings. Of the 140 applicants, James H. Howard was one of only fifteen that made the final cut to enter training to determine if he had the makings of a Navy pilot.

Thirty days at Long Beach introduced Navy Seaman Second Class Howard to military drill, aviation theory, aircraft mechanics, and ten hours of dual flight instruction in an OU-2 trainer. Before returning home to St. Louis to await further orders, Jim Howard successfully completed all aspects of his initial training including his first solo flight.

Just before Christmas 1937, with orders in hand, Howard reported to the Naval Training Station at Pensacola to join sixty-nine, other would-be aviators, in Class 109-C. In the year that followed this pilots-in-training flew every type of Naval airplane imaginable, learning to deal with every conceivable circumstance, while moving through five different levels beginning with Squadron One. It was rigorous and demanding training, and by the time James Howard got his last check-up with Squadron Five in January 1939, thirty-two of his classmates washed out. Those who completed the course received a ceremonial sword and gold aviation wings. James Howard was now an Aviation Cadet, USNR (U.S. Naval Reserve), the lowest of the Navy's officer ranks.

After returning home to proudly display his uniform to his proud parents, Aviation Cadet Howard was assigned to Fighting Squadron Seven (VF-7) on the brand new aircraft carrier Wasp, which was still undergoing shake-down in the Atlantic. In the interim, in March 1939, Howard was sent to San Diego to fly F4F-1 biplane fighters as part of a fighting squadron assigned to the carrier Lexington. For three months all of his flights were ground-based; he had yet to take-off or land on a carrier. In June Howard received orders to travel to Norfolk, Virginia, to join VF-7. It would turn out to be simply another step in a continuous shifting of orders that left him looking for his place in the Navy. When he arrived at Norfolk the Wasp was still at sea and Howard was assigned to the Ranger, again spending several months flying only land-based familiarization flights, this time in the F2F.

When at last the Wasp was ready the Navy discovered its roster of pilots ill-timed for rotation, and new orders were cut sending Howard to Fighting Squadron Six of the USS Enterprise, which would ultimately become legendary during World War II as the "Big E."

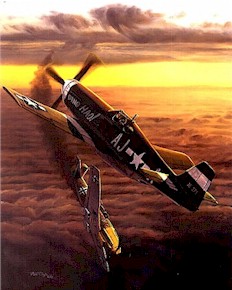

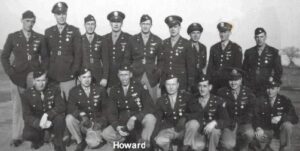

Shortly after James Howard arrived in San Diego the Big E cruised west to Hawaii. Howard and the other pilots who had yet to make their first carrier landing boarded the ship before it departed. The remaining pilots and planes flew in to land on her deck while the carrier was at sea. During the following four months in and around Pearl Harbor, Howard, at last, began a regular routine of taking off and landing on the floating airfield. His fighter was a Grumman F3F-2 and was #6F12 in the squadron (pictured behind Howard in the photo above.) During four months of practice for warfare, Howard flew near-daily missions to hone his gunnery skills and dive-bombing techniques. By the time the Big E returned to San Diego, he had become a proficient combat pilot.

By the time Howard had been aboard the Enterprise for nearly a year, war broke out in Europe and the United States was jockeying for a position of neutrality. Though the threat appeared to be primarily in Europe, Japanese aggression in Asia could not be ignored, and five of the United States' six aircraft carriers were ultimately assigned to the Pacific theater. Throughout 1940 and early 1941 the carriers rotated out of West Coast Naval Bases to Hawaii for continued maneuvers to prepare their men for possible war. Along the way, James Howard was promoted to Ensign, and upon his return to San Diego early in 1941 received a rare and high compliment from the U.S. Navy. A board of officers advised Ensign Howard that after review of his two-year record of service, the Navy was prepared to offer him a regular commission. It was an offer extended to only one other member of Fighting Squadron Six and provided the young pilot unusual opportunity for a Naval career. Howard recalled that meeting by writing:

"I really agonized over this, for these officers had considered me superior. A 'no' answer would amount to a repudiation of their confidence in me and a denial of the importance of their careers in the Navy."

"I finally blurted out, 'Please forgive me for giving you a negative answer. I have always thought of the navy not as a career but as an adventure. I may rue this day, but at this moment I must gratefully reject this offer.'"

Howard's declining a regular commission was a timely and fateful decision. The following April when President Roosevelt authorized the American Volunteer Group, his order provided for recruitment from reserve officers and enlisted personnel of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. Thus, it was that in the Spring of 1941 Ensign James H. Howard found himself submitting an application to resign from the Navy and join a group of volunteer airmen in a dangerous and dramatic one-year mission to China. On June 12 his orders came through; his application had been accepted.

In a very real sense, though he was a proud and patriotic American, James Howard was going home!

Airmen in Burma

Claire Chennault personally greeted the first group of A.V.G. pilots in San Francisco as they gathered for a July 10 departure to China, to join a small group of ground personnel that had departed for Rangoon two weeks earlier. The 121 young men, including 33 pilots, came from all walks of life and from all branches of military service. Like Ensign Howard, each had resigned from their respective branches of military service in order to serve as American civilians on foreign shores. Their lot included three doctors and a dentist. Two female nurses completed that first major group of CAMCO employees.

Claire Chennault personally greeted the first group of A.V.G. pilots in San Francisco as they gathered for a July 10 departure to China, to join a small group of ground personnel that had departed for Rangoon two weeks earlier. The 121 young men, including 33 pilots, came from all walks of life and from all branches of military service. Like Ensign Howard, each had resigned from their respective branches of military service in order to serve as American civilians on foreign shores. Their lot included three doctors and a dentist. Two female nurses completed that first major group of CAMCO employees.

"The President has assured us that, as long as we fight for a country that professes democratic faith, your citizenship will remain intact," Chennault advised his volunteers. "You will be officially part of the Chinese military so you won't be classified as a war criminal if you are captured."

On July 10 the Dutch steamer Jagersfontein departed San Francisco en route to Burma by way of Pearl Harbor and Singapore. The 123 A.V.G. passengers carried passports listing them as missionaries, farmers, salesmen, students, acrobats--anything but what they truly were--adventurers embarking on one of the most unusual military missions in American history. Though Chennault had told them all "this mission is considered secret," he had further noted, "it won't be secret for long." It wasn't! Even as the steamer passed beneath the Golden Gate Bridge Radio Tokyo announced that the Jagersfontein would be sunk before it ever reached the Far East. The pseudo-secrecy and manipulation of the status of these American citizens were actually little more than a routine of political expediency. Since Japan had never declared war on China, despite waging years of combat against the Chinese people, the arrival of these American civilians did not violate any sense of neutrality in the ongoing conflict.

In spite of Radio Tokyo's threat, the Jagersfontein reached Rangoon safely, where the volunteers boarded an aging train for the seven-hour journey of 160 miles into central Burma. There, seven miles beyond the town of Toungoo, the A.V.G. set up shop at the Kyedaw Airdrome that had been constructed by the R.A.F. but never used. "This is the stink hole of the world," proclaimed one of the now-veteran members of the ground crew that had arrived two weeks earlier. Jeered another, "Your barracks have no screening. All the bugs of Asia are here to greet you. There's no hot water and the latrines are out in the boondocks, where you have to step over snakes along the way." About the only thing in short supply at Kyedaw Airdrome was airplanes--only two of the promised 100 aircraft had been assembled at Rangoon and flown to the muddy airfield.

The new arrivals were divided into three squadrons by their temporary commander, retired Army Air Corps Captain Boatner Carney. Bob Sandell was appointed squadron commander for the First Pursuit Squadron, Jack Newkirk commanded the Second, and Arvid Olson the third. The appointments were hastily made in a desperate attempt to establish order in the ranks, placing James Howard in the Second Squadron under the command of a fellow Navy pilot who was his junior. Howard masked his disappointment at being passed over and welcomed Newkirk's decision to make him his deputy. In the months that followed the three squadrons would develop their own identities, along with distinctive squadron insignia.

When Claire Chennault flew into Toungoo to begin building these three squadrons into an air force he found himself facing a nearly impossible task. Ten men greeted him with resignations as quickly as he arrived and others were seriously doubting the wisdom of their decision to join the A.V.G. despite the high pay and the promise of a five-hundred-dollar bonus for every enemy airplane destroyed. "The recruiting was done fairly with an appeal to patriotism and adventure," Chennault reminded his remaining pilots and ground crews. "If your hearts and minds are not in the proper place, we have no place for slackers."

The following day the training regimen began for those who stayed on. Every pilot who arrived before September 15 received seventy-two hours of lecture that ranged from history to tactics. "I gave the pilots a lesson in the geography of Asia that they all needed badly, told them something of the war in China, and how the Chinese air-raid warning net worked," Chennault recalled.

"I taught them all I knew about the Japanese. Day after day there were lectures from my notebooks, filled during the previous four years of combat. All of the bitter experience from Nanking to Chunking was poured out in those lectures. Captured Japanese flying and staff manuals, translated into English by the Chinese, served as textbooks. From these manuals the American pilots learned more about Japanese tactics than any single Japanese pilot ever knew." (Chennault)

As additional P-40s were assembled and flown into Toungoo each pilot also began sixty hours of flight training. The flight practice was sorely needed, as was evidenced by numerous minor accidents that sent several damaged aircraft up to the CAMCO factory at Lowing, China, for repairs. A mid-air collision on September 8 destroyed two fighters and caused the death of the first A.V.G. pilot, John Armstrong. Two weeks later two more pilots died in training accidents.

Additional volunteers continued to arrive in September and October but training accidents continued to deplete the inventory of flyable fighters as quickly as resignations depleted the ranks of the A.V.G. personnel. Ten former Navy pilots arrived at Toungoo on October 29 and as quickly as they arrived, two of them resigned. Chennault noted that of the remainder, "None has the sort of experience we want." One of the eight who stayed subsequently cracked up three fighters in his first week and damaged two others. It was said that he later painted five American flags on his aircraft and proclaimed himself a Japanese Ace.

On November 7 Chennault fired off a nasty letter to CAMCO stating:

I request... that in future a more intelligent employment policy be followed.

In telling the A.V.G. story to pilots who may think of volunteering, nothing should be omitted. Far from merely defending the Burma road against unaccompanied Japanese bombers, the A.V.G. will be called upon to combat Japanese pursuits; to fly at night; and to undertake offensive missions when planes suitable for this purpose are sent out to us. These points should be clearly explained.

Then, after the timid have been weeded out, the incompetents should also be rejected. I am willing to give a certain amount of transition training to new pilots, but we are not equipped to give a complete refresh course. It is too much to expect that men familiar only with four-engine flying boats can be transformed into pursuit experts overnight. No volunteer should be accepted in any category whose record does not show sufficient experience in that category to limit the transition training to teaching the peculiarities of a new plane.

Let me repeat, much money and much irreplaceable equipment has already been wasted, the A.V.G.'s combat efficient seriously lowered, by the employment policy that has been followed. I am aware that this policy makes it far easier to fill the employment quotas. But I prefer to have the employment quotas partly unfilled, than to receive pilots hired on the principle of "Come one, come all."

That letter would prove to be unnecessary. Though recruitment had been planned for a second A.V.G. the following year, world events halted the program. The last group of twenty-six pilots assigned to the First A.V.G., including Greg Pappy Boyington who would later earn the Medal of Honor as a Marine Corps ace, arrived on November 12 to begin training. By the end of the month Chennault had 82 pilots, some of whom had not yet checked out in the Tomahawk. Of his seventy-nine P-40 fighter aircraft, seventeen were out of commission and two more had yet to be fitted with radios and guns. The A.V.G. was quite unprepared for war when, seven days later, the war came to them.

December 8, 1941

Less than one hour had passed in a new day at Toungoo when World War II, at last, forced itself on the United States of America. On the other side of the International Date Line, it was 7:55 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, when more than 300 Japanese carrier-launched aircraft unleashed unprecedented fury on Pearl Harbor. It was the kind of deadly aerial assault Japanese pilots had practiced to perfection for four years in the cities of China. By the time a telegram with news of the attack in Hawaii reached Chennault at dawn, the U.S. Pacific fleet lay in ruins and more than half of the 230 Army Air Force fighters and bombers based in Hawaii had been destroyed or damaged.

Less than one hour had passed in a new day at Toungoo when World War II, at last, forced itself on the United States of America. On the other side of the International Date Line, it was 7:55 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, when more than 300 Japanese carrier-launched aircraft unleashed unprecedented fury on Pearl Harbor. It was the kind of deadly aerial assault Japanese pilots had practiced to perfection for four years in the cities of China. By the time a telegram with news of the attack in Hawaii reached Chennault at dawn, the U.S. Pacific fleet lay in ruins and more than half of the 230 Army Air Force fighters and bombers based in Hawaii had been destroyed or damaged.

Before Chennault could call a meeting of his staff and squadron commanders, Japanese twin-engine bombers had destroyed eight of a dozen new Marine Corps Wild Cats on the ground at Wake Island. As Chennault briefed his squadron commanders the news continued to come in of more attacks. That news was all bad! Within hours of the sneak attack at Pearl Harbor Japanese forces followed with simultaneous assaults on Guam, Thailand, Malaya, Shanghai, Peking, Hong Kong, and Singapore. By the time Chennault's briefing concluded, the last remnants of American airpower in the Pacific lay in ruins at Clark Field in the Philippines.

For the men of the A.V.G., those first forty-eight hours were gut-wrenching. Several A.V.G. pilots including James Howard had come from the Navy, had flown out of Pearl Harbor, and had friends still serving there. Many of them were torn between a desire to return home quickly to rejoin their comrades in defense of their own nation, amid the realization that as members of the A.V.G. in Burma they were probably the only American airmen remaining in a position to avenge the "Day of Infamy." Just how critical their position was becoming abundantly clearer with each passing hour.

Within 48 hours of the attack at Pearl Harbor, Guam had fallen, British forces were forced to retreat in Malaya, and the British ships Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk in a twenty-minute bombardment by twenty-seven Japanese airplanes. More than 800 British sailors were killed in that attack which left the Pacific waters nearly defenseless.

On December 9 China declared war on Japan. On that same day, Thailand capitulated, opening the way for Japanese ground forces to launch an invasion of neighboring Burma.

On December 10 the first Japanese ground forces began landing on the north side of Luzon in the Philippine Islands, forcing Philippine Scouts and their American allies backward for a valiant but futile defense on the Bataan Peninsula.

On December 12 Japanese infantry and artillery began their invasion of Burma, streaming across the Thai border. When British forces were forced the following day to withdraw from the mainland to Hong Kong Island, the only opposition remaining in the Pacific was a beleaguered Marine force at Wake Island, a few valiant Canadian soldiers still struggling to hold Hong Kong Island, a vastly outnumbered British garrison at Singapore, a determined but doomed Philippine resistance on Bataan, a small R.A.F. squadron with thirty-six outdated Brewster Buffalos at Rangoon....and Claire Chennault's small A.V.G. air force at Toungoo.

Flying Tigers

As the Japanese continued their invincible assault on Asia and the Pacific, in Burma Claire Chennault went into action. He sent his third squadron of Hell's Angels to Mingaladon Airdrome near Rangoon to support the meager R.A.F. forces in their mission of protecting the important port city. His ground crews, numbering slightly nearly 200 volunteers, began the long trek across the Burma Road to the A.V.G.'s new base at Kunming, China.

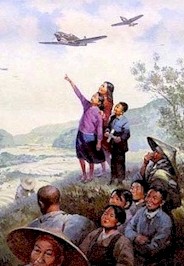

On December 18 the First and Second Squadron pilots flew their P-40s to Kunming, eager to settle into the more modern facilities of what was to be their main base of operations. The sight that greeted them was not what they had anticipated. Claire Chennault had long lectured his men about the war that had raged in China for years and the disastrous toll it had taken on a proud people of an ancient empire. He had spoken of his intelligence network that gave advanced warning of incoming Jap bombers and the cries of "jing bao" that echoed through the cities to hasten innocent civilians to shelter before the enemy appeared, unmolested, to rain death on men, women, and children too slow to escape. The American pilots knew such tragedy had stalked China for years, but before their arrival at Kunming such tales were merely second-hand accounts of the savagery of the Japanese air force.

On December 18 when Chennault's pilots, at last, arrived in China itself, they came face to face with the reality of war. The enemy had struck the day before, killing more than 400 civilians with their deadly bombs. When the First and Second Squadrons arrived at Kunming it was to find the streets still littered with the body parts of women and children, struck down by unchallenged enemy bombers. Author Russell Whelan notes:

"To the men of the A.V.G. it was astounding and infuriating. Every last one of them was glad, then, that he had come do something about such evils as this."

Two days later the Japanese returned with ten unescorted bombers. For the vaunted Nippon air warrior, such missions were routine; for four years there had been no air force in China to challenge them, no opposing airmen to dissuade them from their deadly forays, and no warriors of the air to protect the hapless civilians in the cities below. On December 20, after two weeks of unprecedented conquest in Asia and the Pacific, the invincibility of the veteran Japanese air force evaporated in the face of a few American pilots flying their first combat mission.

In a matter of minutes nine of the ten enemy bombers fell to fire from outdated P-40s flown by American civilians. Only one P-40 was lost in the A.V.G.'s baptism of fire. After shooting down one bomber Ed Rector had been so determined to make sure none escaped that he had chased the sole survivor until his own airplane ran out of gas and he had to make an emergency wheel's up landing. The following morning, he phoned in from a nearby city that he had survived and was returning to base.

James Howard was disappointed to have missed most of the action. His assignment during that first air battle that had sent First Squadron and part of the Second to meet the incoming enemy bombers, had been to circle the field at Kunming to intercept any bombers that got past the attacking P-40s. None did! In fact, as soon as Claire Chennault's pilots had attacked the inbound bombers, the Japanese pilots jettisoned their load and ran for home. Only one had escaped successfully. More importantly, the people of Kunming had been spared tragedy for the first time in years. The outpouring of their gratitude was prompt and sincere.

Young A.V.G. pilots who one day earlier had been seen only as soldiers of fortune or mercenaries in a foreign land became instant heroes. Russell Whelan recounts, "The grapevine had carried the news of their victory into every shop and home, and as they walked through the streets the Chinese greeted them with wide smiles and cheering calls. The kids of Kunming followed them in jubilant parades, the bolder among them yelling the words 'Fei Hu' (the Chinese for 'Flying Tiger') over and over again to direct the attention of their elders to the heroes.

Young A.V.G. pilots who one day earlier had been seen only as soldiers of fortune or mercenaries in a foreign land became instant heroes. Russell Whelan recounts, "The grapevine had carried the news of their victory into every shop and home, and as they walked through the streets the Chinese greeted them with wide smiles and cheering calls. The kids of Kunming followed them in jubilant parades, the bolder among them yelling the words 'Fei Hu' (the Chinese for 'Flying Tiger') over and over again to direct the attention of their elders to the heroes.

"Word of the aerial victory over the Japanese spread quickly through the province of Yunnan, luring people of the hills to the city to see these brave strangers from beyond the seas and their marvelous wagons that traveled through the sky."

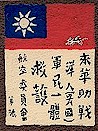

Claire Chennault, mindful of his one pilot who had been forced to make an emergency landing in that first encounter and then work his way through the countryside to return to Kunming, had the words: "I am an aviator fighting for China against the Japanese--Please take me to the nearest communication agency" sewn in Chinese on the back of his pilots' shirts and jackets. In the months that followed as the A.V.G. pilots continued to defend the Chinese from the air, the populace on the ground responded with cheers, thanksgiving, and critical assistance to downed pilots--often at great personal risk.

Claire Chennault, mindful of his one pilot who had been forced to make an emergency landing in that first encounter and then work his way through the countryside to return to Kunming, had the words: "I am an aviator fighting for China against the Japanese--Please take me to the nearest communication agency" sewn in Chinese on the back of his pilots' shirts and jackets. In the months that followed as the A.V.G. pilots continued to defend the Chinese from the air, the populace on the ground responded with cheers, thanksgiving, and critical assistance to downed pilots--often at great personal risk.

A respite came at last to Kunming. Following the Nippon disaster in their first encounter with the city's newly arrived Fei Hu, they never again attempted to bomb the city that was now well-protected by American Flying Tigers.

The winged tiger that became the symbol of Claire Chennault's Flying Tigers was a development that came only after the A.V.G. had been in combat for months and captivated the imagination of the media and public back home. At the request of the China Defense Supplies in Washington, D.C., Walt Disney's artists in Hollywood developed the logo of a winged tiger flying through a "V" for victory, which was soon painted on all aircraft of the A.V.G.

The winged tiger that became the symbol of Claire Chennault's Flying Tigers was a development that came only after the A.V.G. had been in combat for months and captivated the imagination of the media and public back home. At the request of the China Defense Supplies in Washington, D.C., Walt Disney's artists in Hollywood developed the logo of a winged tiger flying through a "V" for victory, which was soon painted on all aircraft of the A.V.G.

Long before the tiger, however, it was the shark that symbolized the aggressive resolve of the A.V.G. The origin of the distinctive white shark's teeth is somewhat vague in the legend of the A.V.G. Some accounts attribute the idea to Eric Shilling, a former Army pilot who noted that the Japanese, as an island people of fishing fleets, "entertained a wholesale fear of sharks," prompting the nose design as an A.V.G. strike at Japanese superstition.

In his autobiography James Howard recounts that: "One day Bert Christman had shown me a picture of a P-40 on the cover of the British newspaper India Illustrated weekly. The plane was being operated by the British from an airfield in North Africa. its nose had been painted with the head of a shark, its sharp teeth glistening from a wide-open mouth. It was a natural. The air scoop behind the propeller made a perfect outline for a shark's head. It was adopted immediately by the three squadrons and painted on all of our planes. Some men even thought that this ferocious image would help to scare the superstitious Japanese pilots and make them turn for home." In fact, the fearsome shark nose had been used by German pilots even before the R.A.F. painted teeth on their P-40s in the Libyan Desert.

Decades later some historians link the tiger to Claire Chennault's alma matter, the Fighting Tigers of L.S.U. For his own part, Chennault later wrote: "How the term Flying Tiger was derived from the shark-nosed P-40s I never will know. At any rate, we were somewhat surprised to find ourselves billed under that name."

Whatever the origin, the unique design that has since been copied by succeeding generations of airmen including helicopter pilots during the Vietnam War, became famous because the men of World War II's A.V.G. lived up to the ferocity of the face painted on the noses of their aging Tomahawks.

The Flying Tigers' first victory on December 20 marked a turning point for the citizens of Kunming who had endured four years of suffering at the hands of Japanese bomber pilots. On the larger scale of events, however, it paled beneath a continuing barrage of bad news for the American public. For two weeks the only ray of hope in a war that seemed lost even before the United States could mount a response had rested with 400 beleaguered Marines at Wake Island. Even that dim glow of optimism was snuffed out on December 23 when the Japanese at last successfully invaded the island and the defenders of Wake were killed or captured.

News of the tragedy at Wake was further compounded for the men of the A.V.G. with the arrival of news that three new Curtiss Wright Type 21 interceptors, after being refueled at Lashio, had been lost that same day in the jungles while en route to supplement the A.V.G. inventory at Kunming. Faulty fuel, not the Japanese, was to blame for the crash that killed Tiger pilot Lacey Mangleburg and forced his two comrades to pancake their own airplanes into a mountainside. If the Flying Tigers were indeed the last hope for any good news on the war front, the untested airmen were faced with not only a daunting enemy but also a diminishing supply of men and machines to face off against an armada that outnumbered them one-hundred to one.

At Rangoon Arvid Olson's Hell's Angels had heard reports of the first Tiger victory three days earlier at Kunming, and eagerly awaited the Japanese assault on Burma that all knew was imminent. Their anticipation was not shared by the half-million residents of Rangoon, all of whom were well aware of the fact that nothing yet had stopped the Japanese onslaught, and all of whom realized that Tokyo had painted a large bull's eye on the important port city. All that existed to rise to Rangoon's defense were about fifty British, Australian, and New Zealand pilots of the R.A.F. with their 36 antiquated fighters, and twenty-five untested Americans with less than two-dozen Tomahawks.

Air raid sirens sounded throughout Rangoon early on the morning of December 23 sending the residents scattering for shelter from an enemy that never materialized. It was obvious that the fear that had spread throughout the city in the preceding 24 hours had made the civilian spotters overly nervous. After a second false alarm a short time later the dock laborers tried to push aside their feelings of impending doom to go to work. The sirens sounded again an hour before noon, but this time they went largely ignored until a formation of eighteen enemy bombers appeared above the harbor to rain a torrent of bombs on the docks below.

Beyond the city, at Mingaladon airdrome there had been no warning of the incoming enemy bombers. Only the sound of the explosions in the distance and rising columns of smoke from the harbor signaled the moment the Hell's Angels had been anticipating. By the time a dozen Tigers and fifteen R.A.F. fighters were airborne, the first wave of enemy bombers had done their work and turned for home leaving disaster behind. Climbing to 20,000 feet the two dozen Allied defenders were just in time to see a second wave numbering thirty bombers coming in for the coup de grace, escorted by twenty Jap fighters.

The Hell's Angels left the fighters to the R.A.F. and dove to intercept the bombers. Henry Hank Gilbert dove on two bombers at once, firing as he passed between them until his own fighter was hit by cannon fire and plunged earthward. He was the first Flying Tiger killed in action. Nearby his comrades, though vastly outnumbered, a dove with abandon on the enemy force. Charles Older, who would become a double-ace with the A.V.G., got his first kill. As his victim's airplane erupted in the sky the explosion and falling debris struck nearby Tiger pilot Neil Martin, sending his Tomahawk plummeting earthward.

The battle was brief and bitterly fought. Paul Greene poured deadly fire into a Nakamima bomber when two enemy fighters jumped him from behind. Forced to bail out, the two Jap fighters did their best to riddle both man and parachute as they followed him nearly to the ground, but somehow Greene survived. In the battle for Rangoon, the Tigers lost three airplanes and two pilots, their first combat casualties. The R.A.F. lost five planes, and virtually all of the surviving aircraft returned to Mingaladon riddled with enemy bullets. The Hell's Angels had been bloodied, had even claimed six enemy bombers and four fighters to slightly outscore the opposition. But knowing that the enemy had nearly a thousand airplanes to continue to throw against fewer than 100 Flying Tigers, the young Americans knew they would have to do better.

Because of the lack of advance warning from the R.A.F., too many enemy bombers had reached the docks at Rangoon to wreak havoc. Fires raged across the harbor and 300 dock workers had been killed in one direct hit on a warehouse. More than a thousand workers, while running for shelter through a poor tenement district, had been shredded by a direct hit from above, and hundreds of civilians had fallen victim to machine-gun fire as enemy pursuit ships strafed a shopping square. The only thing more deadly than the indiscriminate fire of Jap bombers and fighters was the terror that now gripped the city. War had at last reached out to savage the people of Burma, and tens of thousands of immigrant workers from India began fleeing for home. The important supply line inland from Rangoon had, in one deadly attack, been nearly paralyzed.

The enemy did not return on December 24, a day of mourning in Rangoon where fires continued to burn and heartbroken citizens bent to the task of mourning their dead. At Mingaladon the Hell's Angels mourned their own losses while the ground crews hurriedly patched holes in the damaged Tomahawks and the pilots reviewed their failed tactics and planned for the rematch all knew was imminent.

Christmas morning brought more discouraging news as Radio Tokyo bragged of its continuing conquests. In a supreme example of the Emperor's faith in the invincibility of his aerial armada, the broadcaster even bragged to the world that Rangoon could expect "a bundle of Christmas presents shortly."

The Tigers at Mingaladon knew the enemy was coming and, despite the one-day reprieve, sensed that this Christmas Day was the day they would be back. When no alarm sounded throughout the morning, and having lost faith in the R.A.F.'s early warning system, at 9 a.m. Arvid Olson sent three pilots up to fly reconnaissance. Half-an-hour later George McMillan was stunned by the size of the aerial armada he saw approaching from sixty miles out. He radioed Mingaladon just as the R.A.F. sounded the alarm. Three more Tigers quickly took off to reinforce McMillan, to be joined later by seven other P-40s. Facing these thirteen determined young men was a force of sixty enemy bombers, escorted by twenty fighters.

Ten miles out the enemy wave split with nearly half of the force turning to bomb Mingaladon, while the remainder zeroed in on what remained of the docks and warehouses of Rangoon. In moments the Tigers were diving on the bombers headed for the harbor, five of the big enemy planes falling in flames in the opening rush. As Nippon fighters moved in to challenge the Tigers, Chennault's pilots remembered the lessons drilled into them in the preceding months. In a dogfight, the Japanese fighters could outmaneuver the P-40, and the A.V.G. pilots had been warned to avoid the strong desire to engage man-on-man. Instead, they had been instructed to utilize the P-40's two advantages over the enemy airplanes, diving speed, and heavy firepower. On Christmas Day as the veteran air force of the Empire of Japan flew towards Rangoon in their classic formation, the Flying Tigers refused to rise to the bait. They dove and fired, enemy bombers falling right and left with each pass, and then turned their tails to the Jap fighters to outclimb the enemy pursuit and then line up to dive again.

At Mingaladon the R.A.F. paid dearly to protect the airfield; nine Brewster-Buffalos were destroyed and six pilots killed. Their effort had, however, kept the enemy from dropping a single bomb on the aerodrome and claimed eight of the thirty bombers that had split from the main formation to try and wipe out the only remaining threat to Japan's supremacy in the air over Asia. One Jap bomber made a suicidal attempt to crash into the Mingaladon headquarters but missed his target, while the remaining twenty-one bombers jettisoned their loads over the jungle and turned for home.

In the streets of Rangoon, the terrified citizens witnessed an incredible turn of events as Arvid Olson's pilots turned the Emperor's anticipated Christmas Day destruction of the city into a rout. Olson later telegraphed Chennault that it had been "Like shooting ducks!" Nippon bombers and fighters fell all across the jungle beyond the city as two Flying Tigers each racked up an amazing four kills within minutes of each other. Quickly the demolished enemy formation was scattered and fleeing for home with shark-nosed P-40s in hot pursuit.

In the streets of Rangoon, the terrified citizens witnessed an incredible turn of events as Arvid Olson's pilots turned the Emperor's anticipated Christmas Day destruction of the city into a rout. Olson later telegraphed Chennault that it had been "Like shooting ducks!" Nippon bombers and fighters fell all across the jungle beyond the city as two Flying Tigers each racked up an amazing four kills within minutes of each other. Quickly the demolished enemy formation was scattered and fleeing for home with shark-nosed P-40s in hot pursuit.

The enemy's planned Christmas surprise for the day was the second wave of twenty bombers and eight fighters, arriving late to perform what they anticipated would be a simple mop-up after a glorious victory by the first wave. Olson's Tigers abandoned their pursuit of those already vanquished and turned to meet this new threat. Now too low to dive, the shark-nosed P-40s resorted to an unorthodox upper-cut, flashing in low and beneath the enemy with guns blazing to rip them apart. Robert Smith destroyed one enemy at so close a range that disintegrating metal from the Nakajima's motor was embedded in his Tomahawk. Ed Overend, after claiming two victories, was forced to break off with more than 100 bullet holes in his own airplane. Parker Dupouy found himself under attack by two enemy planes and flamed one before his guns jammed. Diving towards the remaining fighter he determinedly and intentionally passed close enough for the dueling wings to impact. The fragile Japanese airplane broke apart, while the sturdier P-40 turned for home with four feet of the right-wing missing.

Eleven of the thirteen Tomahawks that had risen to engage more than seventy-five enemy returned to Mingaladon when the thrashing was over. Ed Overend and George McMillan returned to Mingaladon the following day after making emergency landings in the jungles.

"Final accounts of the victories varied widely. Officially credited to the A.V.G. were thirteen Jap bombers and ten fighters, a total of twenty-three planes. Leland Stowe, the American war correspondent who flew to Rangoon immediately after news of the astounding Jap defeat reached the outside world, reported that the Tigers had brought down at least twenty-eight planes. The Tigers estimated six additional victories over the Gulf of Martaban, where the Japs had sunk without evidence. In any case, it was established beyond doubt that of the one hundred and eight Japanese planes participating in the two Christmas Day raids, the Tigers with R.A.F. help, had knocked out at least thirty-six, or thirty-three per cent. In addition, the Japs had lost not less than ninety-two pilots and bomber crewmen, as compared with only five deaths for the R.A.F. and none for the A.V.G." (Whelan)