Mark and Jack Mathis

First Lieutenant Mark Mathis was the eleventh member of the crew of The Duchess when the B-17F departed Molesworth, England, to fly into history on the morning of March 18, 1943. The target on that day was the submarine pens at Vegesack--a strike into Germany itself. The Duchess, under the command of First Lieutenant Harold L. Stouse, was the lead bomber in a formation of 76 Flying Fortresses of the 8th Air Force's 1st Bombardment Wing. These bombers were supplemented by twenty-seven B-24s from the 2nd Bombardment wing, bringing the total number of aircraft to more than 100. It was the largest American bombing mission yet mounted in World War II.

Staff Sergeant Eldon Audiss recalled that mission well in a recent phone interview. As The Duchess' engineer, Sergeant Audiss was supposed to know more about his airplane than any member of the crew. If the bomber was attacked it was his job to operate the top turret, becoming one of the B-17's gunners. Throughout the mission, he worked closely with the pilot and co-pilot monitoring engine operation, fuel consumption, and the operation of all the equipment. He also assisted the radio operator and bombardier with their own important tasks.

"On that day The Duchess was the only bomber fitted with the Norden bombsight," he recalled. "That made our role as the lead bomber very important. When our bombardier released his bombs, the other aircraft would bomb on his lead. If we missed, everyone would probably miss."

The bombardier upon which the success or failure of the mission against Vegesack rested was Mark Mathis' younger brother, Jack. First Lieutenant Jack Mathis was a seasoned bombardier who had flown his thirteenth combat mission just five days earlier. For the men of the 8th Air Force "thirteen" was considered a lucky number. It meant passing the halfway point to the magical twenty-fifth mission. Number twenty-six was the flight home for a well-deserved rest. In the early days of World War II, the men of the 8th Air Force had about one chance in five of making that final flight.

Mark's arrival at Molesworth the previous day had almost exempted Jack from the Vegesack mission. The two brothers had not seen each other since their training days the previous summer, following which they were sent to serve in different theaters. Mark had flown B-26 missions in North Africa while Jack was assigned to the 303rd Bombardment Group at Molesworth.

Mark's B-26 unit had been transferred to England on March 11, but it took six days for him to get a pass and travel to Molesworth. On the evening of March 17, the two brothers from Sterling City, Texas, were at last reunited half a world away from home. Needless to say, there was a major celebration in the officers' club that evening.

Mark fit in well with the B-17 crews, who were fascinated by his stories of combat in North Africa. The Duchess' radio operator, Staff Sergeant Donald Richardson recently recalled, "Mark was a really great guy, and happy to be out of North Africa. He told stories of flying so low (in the B-26s) that the bombers were pelted by rock-throwing civilians on the ground."

As Mark shared his own stories, Jack did his best to convince his older brother to seek a transfer to the 303rd Bombardment Group, which later became affectionately known as Hell's Angels. "This is the best squadron (359th Bombardment Squadron) in the Air Force," he proclaimed, "and The Duchess is the best plane in the squadron." Jack was preparing to return home early for pilot training, and it was his hope that his brother might take his place on the bomber crew of Lieutenant Stouse.

Mark was eager to make the transition from B-26s to the Flying Fortresses so much of the talk that evening centered around Mark's potential transfer. Though ultimately that transfer would take a few weeks, most who recall the party at the Molesworth officers' club on the night of March 17, felt that Mark Mathis became the eleventh member of The Duchess that very night.

Eager to spend as much time with his brother as possible, Jack asked his friend, and fellow bombardier, Robert Yonkman if he would replace him in The Duchess the following day. Lieutenant Yonkman quickly agreed and accepted the proffered incentive of a bottle of rum from Jack. To finalize the altered plan Jack quickly sought permission from squadron commander, Captain William Calhoun who had known both of the Mathis brothers during their early days of training back in Texas.

Captain Calhoun offered a little incentive of his own, advising Jack Mathis that if he would fly the following morning's mission, upon his return he would be given a pass that would allow him a couple of days of unrestricted fellowship with his brother. Since the Vegesack mission of March 18, fell on a Thursday, such a pass would allow the two brothers to spend most of the weekend together--perhaps even allowing a visit to London if they wished.

Jack quickly agreed, then requested permission for Mark to fly with him on the Vegesack mission. It was a request that involved too many formalities, roster adjustments, and general breaches of Air Force policy. Captain Calhoun denied that request.

Early the following morning Mark arose with his brother and rode with him to the flight line. As the two men stood beneath the wings of the huge Flying Fortress, Jack again reminded his brother that he would be going home soon and that he hoped Mark would be able to transfer to the 303rd to take his place in the nose of The Duchess. To allow the brothers extra time to visit before take-off, other members of the crew chipped in to ready for the flight. Navigator Jesse Elliott stowed Jack's gear in The Duchess and mounted both of the forward guns that he and the bombardier would man inside the bomber's nose. Then someone advised Jack it was time and the bombardier turned to the board.

"See you, boys, at six o'clock," Mark Mathis shouted above the noise of the bomber's four big engines.

"Sweat us out on this one," Jack shouted back before disappearing with a wave.

The Duchess was first to take off, but Mark remained on near the runway with Joe Strickland, one of the ground crew, until the last of the B-17s had faded in the distance. Then he rode back to the officer's club to anxiously await the return of his brother. Though denied permission to fly with Jack on this important mission, Mark Mathis was indeed the eleventh member of the crew that day, for his heart and prayers were in the Plexiglas nose of The Duchess as it flew across the English Channel towards the heavily defended submarine pens in the north of Germany itself.

The Mathis Brothers

Rhude Mark Mathis, Jr., was born in the small town of Sterling City, Texas, on February 14, 1918, the first child of Rhude Mark, Sr., and Avis C. Mathis. Nearly three years later on September 25, 1921, Jack was born in nearby San Angelo. A third son, Harrell C. Mathis, was born to Rhude and Avis seven years later on December 2, 1928.

In the decades since the end of World War II, San Angelo has been quick to claim the two most well-known bombardier brothers of that war as native-sons, much to the chagrin of the small town where the boys actually grew up. In truth, young Jack remained in San Angelo little more than the time that it took him to enter the world and draw his first breath. In the years that followed San Angelo would figure prominently in the lives of both boys, more so when they became young men and entered military service. Fortunately, the legend created in World War II by the Mathis Brothers was large enough to be appropriately shared by both cities.

Sterling City was little more than a pit-stop on Highway 87, a community numbering only a few hundred citizens when the Mathis brothers were growing up. Mark attended Sterling City High School for two years, then dropped out to work at odd jobs in his hometown as well as nearby San Angelo. Jack entered Sterling City High School in 1936 and remained with his studies to graduate on May 16, 1940. The graduating class that year numbered thirteen students.

Less than one month after graduating high school, on June 12, Jack Mathis enlisted in the United States Army. As a young boy, he had shown increasing interest in the airplanes that sometimes flew over Sterling City, but in those pre-war years, the Army Air Corps required applicants to have at least two years of a college education. Jack was assigned to Headquarters Battery, 2nd Battalion, 19th Field Artillery, at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. A studious young man with attention to detail, Jack soon became the unit reporter for the Fort Sill Army News. He also advanced in grade to the rank of Corporal.

The same month that Jack Mathis left for Oklahoma, with the prospects of a world war looming, the War Department selected San Angelo as the site for a new airfield to train pilots. The following January, Goodfellow Airfield opened under the Command of Colonel George M. Palmer. The increased activity associated with establishing the airfield attracted the attention of Mark, who traded his series of odd jobs in the area for a more stable position with the U.S. Army Air Corps. He was assigned as a ground crew member of the 49th Squadron at Goodfellow Airfield, where he could be close to home and his mother, recently divorced.

When Jack learned that his older brother had joined the Army, he managed to transfer to the same 49th Squadron to serve as one of its clerks. The Army offered him additional training, and Jack was able to attend a 16-week administrative course at San Angelo Business College. Both boys now served together, close enough to home to visit frequently. The cadre under which they served was also top-notch, which certainly had some bearing on their own development as soldiers. The 49th Squadron commander under which they both served was Lieutenant Leon R. Vance, who would earn a posthumous award of the Medal of Honor with the 8th Air Force three years later. One of the flight instructors at Goodfellow was Lieutenant Horace S. Carswell who also earned a posthumous Medal of Honor in World War II.

During the summer of 1941, while Mark and Jack went about their separate duties at Goodfellow, the U.S. Army Air Corps underwent sweeping changes. These including a change of name to that of the U.S. Army Air Force, and a rapid expansion in both aircraft and personnel. By the time the United States was catapulted into the World War with the December 7, 1941, attack at Pearl Harbor, the Army air arm's long-standing policy of requiring at least a two-year college education for candidates was loosened. Both Mark and Jack requested transfers to the Army Air Force and were accepted. On January 11, 1942, the two Mathis brothers left San Angelo together for aviation training.

Bombardier Brothers

Mark and Jack Mathis arrived for their initial pre-flight training at Ellington Field near Houston. Upon completion, they both hoped to enter bombardier school. This was an intensive program designed to turn young men into capable bombardiers, able to accurately place their bombs on an enemy target from distances as close as a few thousand feet or as far away as five miles.

Sometime during the month of February, the brothers were separated, though not by choice. An account by Sergeant James Dugan that was published in Every Week Magazine indicated that it was "Mark's nimble tongue (that) split up the brother team." His razzing of a civilian math instructor resulted in a report to the commandant of cadets, who disciplined the older brother by holding him back for three weeks. Thus, it was that when Jack completed his pre-flight training and headed to Victorville Field in California for

advanced bombardier training, Mark was still three weeks away from finishing his pre-flight training at Ellington Field.

Located 65 miles northeast of Los Angeles, Victorville Field was one of the newest twin-engine pilot training schools. It opened on December 18, 1941, and graduated its first class of seventy-five bombardiers on March 3, 1941, thirteen days before Jack Mathis arrived to begin his own training.

Bombardiers were introduced to the highly secret Norden bombsight after first taking an oath to defend it even at the cost of their own lives. During the intensive 12-week program that followed, they dropped nearly 200 bombs in both daylight and night-time practice missions. Records were maintained to score hits and misses and the school washed out more than 10% of those who began the program.

During the period of advanced training, the bombardier became part of a team. He was assigned to complete his preparations with that team, which would become the crew of an American bomber. On June 24 Jack was assigned to a 10-man crew under First Lieutenant Harold Stouse of Spokane, Washington. On July 4, he earned his wings and graduated with Class 42-9. (Lt. Harold Stouse's Original Crew - Pictured Below)

(Front) S/Sgt Eldon Audiss, Engineer; S/Sgt Donald Richardson, Radioman; Sgt Theron Tupper, Waist Gunner; Sgt John Garriott, Ball Turret; S/Sgt Calvin Owen, Tail Gunner

Following his own successful completion of pre-flight training, Mark Mathis was sent to Midland Army Airfield in Texas for advanced bombardier training. By the time he earned his own wings and graduated with Class 42-10 on July 23, his kid brother was in Alamogordo, New Mexico, finishing the final phases of preparations for combat. On September 15, Jack flew home to visit his mother in Sterling City. He was able to spend two hours with her before duty called him to rejoin his crew as they headed for war.

At Battle Creek, Michigan, Lieutenant Stouse's crew picked up their airplane, a new Boeing B-17F, with the tail number 41-24561 (which was shortened to 124561). Lieutenant Stouse named her:

On October 16, Lieutenant Jack Mathis flew with Stouse and a skeleton crew to Molesworth, England, an RAF (Royal Air Force) base north of London, between Peterboro and Cambridge. There they were to begin a series of daylight bombing raids, mostly over-occupied France, with the 8th Air Force's 303rd Bombardment Group. Jack's squadron in the 303rd was the 359th Bomb Squadron.

The 8th Air Force under Brigadier General Ira Eaker had arrived in Britain on May 12, 1942. Eighteen of the general's B-17Es from the 97th Bombardment Group conducted the first American B-17 bombing raid in Europe against the railroad marshaling yards at Touen-Sotteville, France, on August 17, 1942. Additional missions were mounted through October until General Jimmy Doolittle began forming the new 12th Air Force for support of Operation Torch, the American landings in North Africa. By the time the 303rd arrived at Molesworth in October, the focus had been diverted to that important offensive, and the 8th Air Force had been stripped badly by the 12th. The combat-experienced 2nd, 97th, 99th, and 301st Bombardment Groups were transferred to the 12th Air Force leaving a void that the 303rd, despite its best efforts, would be unable to fill for considerable months.

On November 16, the 303rd finally got orders for its first mission, a high-altitude bombing attack on the submarine pens at St. Nazaire on the coast of occupied France. Sixteen B-17s took off from the field at Molesworth at 0923 the following morning, to be joined en route by 47 B-24s from the more experienced 93rd Bombardment Group.

The Best Seat In The House

Ten highly trained men comprised the crew of each of the Flying Fortresses. Every man was part of a team that in most cases, had been assigned months earlier during the late phases of training. Each 10-man crew silently hoped that his team would remain together for the magical 25 missions that would be followed by a well-earned trip home.

In the left-hand seat of the cockpit of each bomber flew the team leader, the aircraft's pilot who also served as each team's commander. On the ground, he was responsible for all aspects of the crew's safety and proficiency, from training to morale. In the air he directed the mission, skillfully manning his four-engine bomber through the dangerous skies towards its objective. Literally at his right hand sat the co-pilot, monitoring the engine and cruising controls, logging all performance data, communicating with the pilot, and standing ready to assume command of the bomber if tragedy struck the pilot.

Five to six enlisted men were scattered through the fuselage to assume varied roles as well as to operate a bevy of belt-fed 50-caliber machineguns. The top turret gunner manned a highly maneuverable Plexiglas console in the bomber's ceiling just behind the cockpit. Waist gunners manned heavy machine guns on either side of the bomber and a tail gunner protected the aircraft from being attacked from the rear. One of the gunners doubled as the bomber's radio operator, maintaining the communications equipment that kept all members of the crew in touch with the pilot and each other.

The top turret gun was usually manned by the flight engineer, who also worked closely with the pilot and co-pilot to monitor engine operation and fuel consumption. His was a broad and important role, rendering assistance to the radio operator and bombardier as well.

The navigator was critical to the success of each mission. Seated forward in the nose of the bomber, he directed the flight from takeoff to return, plotting the position and direction of the aircraft at all times and forwarding that information to the pilot. The 303rd Bombardment Group was one of the first groups to add cheek guns to the front of their B-17s and, when the enemy attack became overwhelming, the navigator could quickly become a skillful fighter.

For nine men of the bomber's crew there was a primary, and then a secondary mission. First and foremost, the team had to work together to reach their assigned target despite difficult weather, enemy fighters, anti-aircraft fire, and other obstacles. Secondary to this was the responsibility to safely navigate home from that target so their Fortress could reload and fly again against the enemy of freedom. In between these two missions lay the most important task of all, accurately dropping the aircraft's bomb load on the assigned targets--sometimes five miles below. Every man's job was important in getting the bomber on the station but to the bombardier fell the ultimate responsibility for the success or failure of the entire team.

On November 17, Lieutenant Jack Mathis was a bombardier in the plane flown by the squadron commander, Major Eugene Romig. Mathis' position was forward of the navigator in the clear Plexiglas nose of the Flying Fortress. It was a vantage point that gave him a panoramic view of the countryside below and, during the bombing run, it was the position from which he could look through the scope of the Norden bombsight to accurately drop his payload. If an aerial fight ensued, he had nearly 180 degrees of unobstructed visibility both horizontally and vertically. B-17 crew members often stated that the bombardier had the best seat in the house. Of course, all knew that it was also a dangerously exposed position that could quickly become a death trap.

On that first mission for the 303rd, Jack Mathis experienced neither danger nor a panoramic view. The formation flew towards St. Nazaire unopposed, only to find the target socked in by a heavy fog. All sixteen Flying Fortresses returned to base with their bomb bays still loaded, their crews fighting only a big dose of disappointment.

Once the 303rd became active the pace accelerated. Twenty-one of the group's bombers flew on November 18, intending to bomb another target in occupied France. Somehow the formation became lost and arrived over St. Nazaire instead, this time with visibility greatly improved. All but two of the Fortresses released their bombs on the submarine pens with solid results. Before that first week of combat ended there were two more missions: to Lorient, France, on November 22, and then back to St. Nazaire on November 23. On that last mission, the 303rd suffered its first loss.

Lieutenant Mathis missed out on all three missions and had to wait nearly three weeks until December 6 to fly his second mission. From that date until the end of January 1943 the 303rd flew nine missions and Mathis flew in all but one, most of them with Lieutenant Stouse in The Duchess.

On that December 6 mission, Jack dropped his bombs on the Carriage and Wagon Works at Lille, France. The B-17s were attacked by 20 enemy fighters that caused slight damage to five of them, but all of the group's bombers returned home safely. Six days later The Duchess was in the air again and headed for Rouen, on the northern coast of occupied France. Eight of the B-17s had to abort due to mechanical problems, The Duchess among them. Two of the Fortresses that continued on were shot down becoming the first losses for the group since November 23.

Jack's fourth mission was part of a 21-plane flight to bomb the Air Depot at Romilly-sur-Seine. Again, several of the bombers experienced mechanical problems, seven of them being forced to return early. Jack and the bombardiers of the remaining 14 Fortresses accurately hit their targets from 22,500 feet, inflicting great damage. On the return home enemy fighters destroyed one bomber which ditched in the English Channel. All members of the crew of the Zombie were lost.

Upon completion of his fifth combat air mission on December 30, Lieutenant Mathis was awarded the Air Medal for "meritorious achievement." This last 303rd BG mission of 1942 was a strike against the submarine pens at Lorient, France. Lieutenant Stouse's crew flew in a different aircraft named Fast Worker Mark II while The Duchess was undergoing maintenance. Only ten of the 16 Flying Fortresses from the 303rd completed the bomb run. These had to force their way through a screen of forty enemy fighters. Three bombers from other groups engaged in the mission were shot down, but all of the 303rd's Fortresses returned to base.

When the year came to a close on the first missions of the 8th Air Force, the 303rd had flown against eight targets in six weeks. In those missions, the group had fielded 144 aircraft and lost five. The most discouraging statistic was the number of planes that had failed to deliver their payload on target. Of 144 bombers fielded in the period, 55 had returned to base with their bomb bays still full. Bad weather and persistent mechanical problems were proving to be a greater detriment to the Allied bombing offensive than enemy fighters or anti-aircraft fire.

Perhaps, however, the 8th Air Force's greatest enemy in that first year was the campaign in North Africa. The transfer of four bomb groups to the new 12th Air Force had depleted the England-based American Air Force's strength to the point that at no time could more than 50-75 aircraft be mounted for a single mission. AAF bombardment theory as developed earlier at ACTS, promulgated by General Kenneth Walker, and espoused in the statement: "The well-organized, well-planned, and well-flown air force (bombing) attack will constitute an offensive that cannot be stopped," was predicated upon that bombing attack being mounted in flights of more than 100 bombers. Furthermore, in matters of supply and support, the North African campaign had taken priority. Obtaining necessary replacement parts for worn or battle-damaged B-17s based in England was so difficult that crews developed a new acronym--AOG--Always on the Ground. One 303rd BG crew went so far as to name their bomber "AOG-Not in Stock," and some pilots refused to allow their planes to be brought into a hanger for repairs, fearing that they would instead be robbed for parts.

Despite these problems, the determined men of the 8th Air Force did their best to patch up, pick up, and press on. The lids from tin cans were used to patch holes in wings, creative engineering found expedient fixes to minor equipment damage, and when all else failed it was not unusual for a ground crew to do a little moonlight requisitioning.

Targets were generally along the northern or western coast of France: submarine pens, rail yards, and transportation centers. The distances precluded fighter escorts on most missions testing the credibility of the American belief in the tactics of massive, high altitude, daylight bombing raids, or the doctrine that a well-organized bomber formation could not be stopped. With the new year and with the situation in North Africa stabilized, things began improving for the 8th Air Force.

The 303rd flew its first mission of 1943 against St. Nazaire three days into the new year. Submarine pens remained an important target. Enemy U-Boats controlled much of the North Atlantic where massive shipments of men and material were attempting to cross from the United States to England. It was critical to the war effort to stem the near-daily loss of Allied ships to the underwater menaces, and this could best be accomplished by slowing the production of new U-boats. To protect their important submarines, the Germans began steadily increasing their anti-aircraft batteries and fighter protection around the important sub pens. On that January 3 mission, the 303rd lost four of the seventeen bombers dispatched with aircraft from other 8th Air Force bombardment groups. It was the only 303rd mission from December 3 to the end of January that Jack Mathis was not assigned to fly on.

It was also this mission that introduced a new bombing technique the men called bombing-on-the-leader. Under this method, instead of the various bombers in the formation releasing their bombs independently, the bombardiers of trailing aircraft tracked the progress of the lead bomber and released their orbs when they saw it bombs fall. This placed added demands for accuracy on the lead bombardier and prompted the assignment of only the best bombardiers to the lead airplane.

The heavy losses on the mission to St. Nazaire reinforced the effort to develop new flying formations and on January 13 the nineteen 303rd BG Flying Fortresses were dispatched to bomb the Lille Fives Company Locomotive Works at Lille, France, tested a closely grouped design the men called the Combat Box. While the aerial arrangement spaced the bombers so close to each other that some crew members complained, its effectiveness was apparent. Despite the appearance of 15-20 enemy fighters, eighteen of the Fortresses reached their target and dropped their bombs, and not a single plane was lost. Lieutenant Stouse and his crew flew that day in a plane named Holy Mackerel. The bombardier was Jack Mathis; it was his sixth mission.

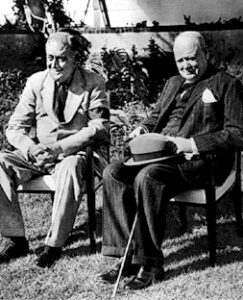

Perhaps one of the most important air missions of 1943 was the one flown two days later by the 8th Air Force's commander, Major General Ira C. Eaker. It was a combat mission of a different nature--a mission from his headquarters in England to an important meeting in North Africa. It was a mission to save the fate of the entire 8th Air Force and to preserve a decades-old doctrine of aerial warfare. Opposing General Eaker would be not only the entire leadership of the Royal Air Force but Prime Minister Winston Churchill himself.

The Casablanca Conference And the Birth of the Combined Air Force

The unqualified success of Operation Torch--the Allied invasion of North Africa, prompted President Roosevelt to  request a face-to-face meeting with the other Allied leaders early in 1943. For Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, it would be the first such meeting since the Arcadia Conference, held in the United States within a month of the attack at Pearl Harbor. At that first meeting, the two leaders and the Allied Chiefs of Staff had wrestled with the problems of a two-front war, agreeing in principle that the defeat of Nazi Germany took precedence over the war in the Pacific. It was an agreement the British took far more literally than did the Americans who had suffered so much at the hands of the Japanese onslaught. Save for a limited number of bombing raids by the 8th Air Force, all American military action in the first ten months of 1942 had centered on the Pacific War.

request a face-to-face meeting with the other Allied leaders early in 1943. For Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, it would be the first such meeting since the Arcadia Conference, held in the United States within a month of the attack at Pearl Harbor. At that first meeting, the two leaders and the Allied Chiefs of Staff had wrestled with the problems of a two-front war, agreeing in principle that the defeat of Nazi Germany took precedence over the war in the Pacific. It was an agreement the British took far more literally than did the Americans who had suffered so much at the hands of the Japanese onslaught. Save for a limited number of bombing raids by the 8th Air Force, all American military action in the first ten months of 1942 had centered on the Pacific War.

Operation Torch was launched in North Africa on November 8, in what many American military planners believed was a political effort to appease British impatience with America's commitment to the European battle. General George C. Marshall and most of the top American war planners had opposed the North Africa campaign, opting to launch a cross-channel invasion of occupied France in 1943. It was a plan favored by most of the British high command as well, despite its eager endorsement by Churchill. Ultimately, Roosevelt and Churchill prevailed over their military commanders. The cross-channel invasion would delay American deployments to the battlefields until 1943 and the American president had promised Joseph Stalin that American troops would engage the Germans before the end of 1942, forcing Hitler to divide his armies and thereby relieve some of the pressure being mounted on Moscow by German forces on the Eastern Front. The ill-fated raid at Dieppe in the summer of 1942 illustrated the dangers of a cross-channel offensive and Churchill and Roosevelt ordered the implementation of Operation Torch.

The battle for North Africa was over in less than a week and by the end of the year, Allied forces were poised to try and turn back Erwin Rommel's Afrika Corps and German dominion in Tunisia. This was the first step to victory in Europe. The conclusion of that campaign necessitated that the Allied leaders and their Chiefs of Staff meet to plan the next steps in the war. Churchill promptly accepted Roosevelt's invitation for a summit at Casablanca in French Morocco stating, "At the present, we have no plan for 1943 which is on the scale or up to the level of events." Surprisingly, Joseph Stalin declined the invitation, advising that he was too occupied with efforts to turn back the Panzer attack on the Soviet capital. In the end, the 10-day conference was attended by Roosevelt, Churchill, and the top military leadership of both nations. To Roosevelt's chagrin, France's two feuding would-be leaders, Generals Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud insisted on attending as well.

Three key elements were on the agenda for the January 14-24 Casablanca Conference and Allied war planners spent the closing weeks of December and the first two weeks of the new year preparing their position papers for discussion.

For all concerned, the first item on the agenda was ensuring that the Allies would remain committed to the pursuit of victory to an unmitigated conclusion. Among Allied nations (England, France, the Soviet Union, and The United States) was a fear that one nation might prematurely reach an agreement with Hitler to cease hostilities, leaving the other nations to continue alone. Indeed, such a prior capitulation had turned control of Northern France to the Axis in June 1940. The Casablanca agreement that all Allied nations would pursue the war until Germany's "unconditional surrender" was, perhaps, the most easily resolved issue.

The second item of business, how to build upon the success of Operation Torch and drive on to Berlin, would not be so easily resolved. General Marshall and most American commanders still opted for a cross-channel offensive through occupied France. Winston Churchill did his best to convince Roosevelt and the Combined Chiefs of Staff that the most logical next step was to proceed across the Mediterranean from North Africa to land at Sicily and then Italy, attacking Germany from its "soft underbelly." Once again, Churchill's war plan won out setting the stage for the Mediterranean Campaign and postponing any cross-channel offensive until 1944 at the earliest.

In addition to discussing and planning the direction of the ground offensive for 1943, the Casablanca Conference tackled the issue of how to proceed with the air war in Europe. While both the RAF and the AAF were committed to the decades-old doctrine of strategic bombardment to destroy the enemy's military and industrial plants and associated supply lines, the two commands differed in their strategy.

The 8th Air Force had flown daylight bombing raids in the last half of 1942, convinced that a large formation of heavily armed bombers could defend itself against enemy fighters and that the daylight would enable greater bombing accuracy. For more than two years, the RAF had flown regular bombing missions against enemy targets in occupied France and Germany. These were almost invariably night missions that allowed RAF bombers to avoid enemy fighters in the darkness.

RAF Air Chief Marshal Charles A. "Peter" Portal prepared for the Casablanca Conference by establishing an RAF position on the air war issue that would have the 8th Air Force joining the RAF for night-time bombing raids in 1943. In the weeks prior to the conference, he discussed the matter with his top commanders, most of whom concurred. In late December RAF Air Vice Marshall John Slessor noted in a letter to British Secretary of State for Air, Archibald S. M. Sinclair:

"Americans are much like other people--they prefer to learn from their own experience. If their policy of day bombing proves to their own satisfaction to be unsuccessful or prohibitively expensive, they will abandon it and turn to night action.

They will only learn from their own experience. In spite of some admitted defects--including lack of experience--their leadership is of a high order, and the quality of their aircrew personnel is magnificent. If in the event, they have to abandon day bombing policy, that will prove that it is indeed impossible."

Vice Marshall Slessor's observations were duly noted along with an additional concern. Sinclair could foresee a major confrontation with AAF Air Chief Hap Arnold on the daytime/nighttime bombing issue that could drive a wedge between the two forces. Two weeks before the conference began, Portal reluctantly backed away from his position of advocating exclusive night bombing missions by both air forces. Only Winston Churchill remained unconvinced, noting the heavy losses the Americans had suffered in their early missions. He was certain that continued daylight raids would sustain that sad trend, and further noted that the American Air Force had not yet bombed beyond occupied France. To win the air war, he believed the AAF would need to join forces with the RAF in massive night bombing missions of Germany itself.

General Arnold countered that his Air Force's heavy losses and restrained missions resulted from the shortage of men and aircraft necessary to mount the kind of bombing mission that was fundamental to U.S. air doctrine. He also recognized that without prompt action, his pilots would never have the opportunity to prove that doctrine, and requested permission to dispatch his 8th Air Force commander to meet with Churchill in Casablanca.

Ira C. Eaker, USAAF

Ira C. Eaker, USAAF

Early in January General Arnold briefed his emissary, Major General Ira C. Eaker, advising that: "The President is under pressure from the Prime Minister (Churchill) to abandon day bombing and put all our bomber force in England into night operations along with--and preferably under the control of--the RAF."

"That is absurd," the 8th Air Force commander exploded! "It represents a complete disaster. It will permit the Luftwaffe to escape. The cross-channel operation will then fail. Our planes are not equipped for night bombing; our crews are not trained for it. If our leaders are that stupid, count me out. I don't want any part of such nonsense."

After attempting to calm down his obviously irate commander, Hap Arnold advised him of the mission to Casablanca. By the time Eaker arrived for the conference on January 15, Arnold, as well as Generals Carl Tooey Spaatz and Frank Andrews, had softened the soil, making plain to the British Prime Minister the American preference for daylight bombing missions.

On January 18, General Eaker met personally with Churchill at the Prime Minister's villa. Churchill later recalled, "I had regretted that so much effort had been put into the daylight bombing and still thought that a concentration upon night bombing by the Americans would have resulted in far larger delivery of bombs on Germany."

General Eaker argued that the 8th Air Force had been hampered in previous missions by poor weather, lack of personnel or aircraft (due to the emphasis redirected to Operation Torch), and the lack of long-range fighter escorts. He noted:

"We have built up slowly and painfully and learned our job in a new theater against a tough enemy. Then we were torn down and shipped away to Africa. Now we have just built back up again. Be patient, give us our chance and your reward will be ample--a successful day bombing offensive to combine and conspire with the admirable night bombing of the RAF to wreck German industry, transportation, and morale-soften the Hun for land invasion and the kill."

Eaker promised Churchill that the 8th Air Force would strike inside Germany before the end of the month. He also asked the prime minister to envision a scenario in which the AAF would bomb the enemy during the day, their explosions lighting fires to direct RAF bombers at night. With such a strategy of around-the-clock bombardment, "The devils will get no rest," he added.

"Young man," responded Churchill, you have not convinced me you are right, but you have persuaded me that you should have further opportunity to prove your contention. How fortuitous it would be if we could, as you say, 'bomb the devils around the clock.' When I see your President at lunch today, I shall tell him that I withdraw my suggestion that US bombers join the RAF in night bombing and that I now recommend that our joint effort, day and night bombing, be continued for a time."

Churchill's concession would, at last, allow American airmen to prove once and for all time, the validity of strategic bombing theories postulated decades earlier by Foulois, Mitchell, Walker, and other early airpower advocates. General Eaker's victory at Casablanca was reflected in the Joint Chiefs' Casablanca Directive when the conference ended. The 7-point treatise, among other things, ordered the 8th Air Force to:

"Take every opportunity to attack Germany by day, to destroy objectives that are unsuitable for a night attack, to sustain continuous pressure on German morale, to impose heavy losses on the German Fighter force, and to contain German fighter strength away from the Russian and Mediterranean theaters of war."

When formally adopted later in the summer, the Casablanca Directive became known as the "Point-blank Directive." It was the basis for the Allies around-the-clock, combined air force strategy to bring Germany to its knees and pave the way for the D-Day landing of 1944. But in January 1943, as General Eaker returned to England, his pilots were looking no further than the immediate goals to demonstrate what they could accomplish in daylight hours.

The 8th Air Force wasted little time before mounting its first bombing raid since the beginning of  the Casablanca Conference. Twenty-one B-17s from the 303rd Bombardment Group joined a formation in an attack on the port area at Lorient and submarine pens near Brest. Lieutenant Mathis flew his seventh mission as a bombardier in the Flying Fortress named "The Idaho Potato Peeler" piloted by Lieutenant Ross Bales. It was nearly Jack Mathis' last mission and ironically, it was with this same pilot that his older brother Mark would later meet his own tragic fate.

the Casablanca Conference. Twenty-one B-17s from the 303rd Bombardment Group joined a formation in an attack on the port area at Lorient and submarine pens near Brest. Lieutenant Mathis flew his seventh mission as a bombardier in the Flying Fortress named "The Idaho Potato Peeler" piloted by Lieutenant Ross Bales. It was nearly Jack Mathis' last mission and ironically, it was with this same pilot that his older brother Mark would later meet his own tragic fate.

Most of the mission went well until the formation was over the target. As the bombardiers prepared for the run the sky suddenly filled with the explosions of heavy anti-aircraft fire and 50 - 100 FW-190 fighters appeared to turn back the American attack. The American airmen braved the intense resistance, dropping their bombs accurately to inflict major damage, but the victory was a costly one--for the 303rd the heaviest losses to date.

Five bombers were shot down over the target. Returning home, the pilot of Werewolf ordered his crew to bail out of their damaged bomber over England and then managed to land with only one engine. The crew of Thumper also bailed out injuring five and killing one man. Her pilot then came in for a wheels-up landing. Lieutenant Bales nursed his battered Idaho Potato Peeler as far as he could, then made a controlled crash landing at Chipping Warden in England. Fortunately, none of his crew which included Lieutenant Mathis was injured.

The 303rd wasted no time licking their wounds. The next mission was scheduled four days later on January 27, and it would be a historic one for the entire 8th Air Force.

Bombs over Germany

The heavy losses from the previous mission left the 303rd able to muster only eleven bombers for the January 27 strike. Lieutenant Stouse and his men were among the eleven flight crews that gathered for the briefing at 0500 and echoed the cheers of their fellows when the map was revealed to show the Fortresses flying north to strike enemy shipyards at Vegesack--within the boundaries of Germany itself.

When the formation took off for the long flight over the North Sea, three of the 303rd's B-17s were forced to abort. The remaining eight led by Captain L. E. Lyle in Ooold Soljer continued on after joining 45 bombers from other 8th Air Force bomb groups.

The mission went unexpectedly well for the enemy was off-guard, never anticipating a strike so deep into its own territory. The mission's only major obstacle was a cloud cover over Vegesack that forced the formation to divert to the alternate target. For Jack Mathis, it was his eighth mission and an exciting one--dropping his bombs over the Wilhelmshaven Naval Base. That evening the returning warriors were welcomed home by a bevy of news reporters, all eager to report that General Eaker had kept his promise to Churchill and bombed Germany before the month of January came to a close.

Though the 303rd flew six missions in February, Jack Mathis participated in only one of them. On February 16 he was back in The Duchess for a mission over the Nazaire port area once again. During that month the 8th Air Force began seeing a major influx of new aircraft, personnel, and replacement parts. Tactics were honed, replacements trained, and the stage was set to inflict major damage in March. Jack missed the first mission on March 4 but flew his 10th combat mission on March 6. The Duchess was the lead bomber in what proved to be a highly successful attack on a power station and bridge at Lorient, France. Jack scored directs hits on the bridge, paving the way for the following bombardiers to accurately place their own explosives.

On March 8 Lieutenant Stouse and crew flew against the railroad marshaling yards in Rennes. On March 12 Mathis accompanied Major Romig once again, this time acting as a bombardier for the 8 Ball MK II. The very next day Lieutenant Mathis returned to the skies, joining Lieutenant Stouse in Knockout Dropper. It was one of those rare missions in which the bombers had fighter escorts to and from the target. Cloud cover hindered the accuracy of the bomb drop but the Americans returned home without any casualties or aircraft losses. For Jack Mathis it was the thirteenth mission; he was halfway to MISSION X, the magical twenty-five that promised combat veterans a well-earned return trip home.

During the time Jack had been flying missions out of Molesworth, Mark Mathis had been serving as a bombardier for a B-24 Liberator in North Africa, where he had been assigned on January 1, 1943. Early in March, his bomber group moved to England, affording him the opportunity to obtain a pass to visit Jack at Molesworth on March 17. Jack found a replacement for his assignment as a bombardier for The Duchess on the mission scheduled for the following day so he could spend more time with Mark, but Major Calhoun convinced him to make that fourteenth mission by promising a weekend pass upon its completion.

Major Calhoun had good reason to want Jack in the lead bomber on the following day's flight. The mission itself was planned to attack important enemy sub pens at Vegesack. It was a mission that included many firsts.

Twenty Fortresses from the 303rd BG would be joined by more than 50 additional bombers from other groups in the 1st Bombardment Wing. Two-dozen B-24s from the 2nd Bombardment Wing would bring the aircraft total to more than 100, making it the largest formation yet flown against Germany.

On this mission, the lead bomber would make its run utilizing Automatic Flight Control Equipment (AFCE) linked to the Norden bombsight. The process had been tested but never before attempted under combat conditions. Under that new procedure, the pilot transferred control of the airplane to the bombardier in the final moments of the bomb run. The Norden bombsight would then direct the path of the bomber until it had dropped its deadly cargo, hopefully, dead on target.

Only the lead bombers in the flights carried Norden bombsights for the raid. The bomb-on-the-leader technique had proven highly accurate and successful since its inauguration on January 3, and continued to be employed. Once the lead bombardier released his payload, the trailing aircraft would unload their bombs on his falling explosives. For this important mission, Captain Calhoun wanted one of his most experienced and skillful bombardiers to lead the way. That man was Lieutenant Jack Mathis.

"No matter what is the opposition...

No matter what the odds are...

We shall never turn back until the target is bombed!"

Lieutenant Mark Mathis watched The Duchess lift off on its mission to Vegesack, standing silently as it quickly faded in the distance at the head of the formation. When the last bomber disappeared, he turned back towards the officer's club to wait and pray, all the while remembering the early-morning conversation with Jack and the consensus that soon Mark would replace him in the nose of The Duchess.

For Jack, there was no looking back. The Best Seat in the House afforded its occupant a panoramic view, but only of what lay ahead, never what was behind. As Captain Stouse powered his engines for altitude, the glass-covered nose of The Duchess revealed only seemingly endless miles of the dangerous waters of the North Sea.

When the formation neared the northern coast of Germany it passed over the small island of Helgoland where the navigator could make any last-minute adjustments for the turn inland towards the target. It was at that moment that 50 - 60 German fighters appeared to intercept the mission. These followed the bombers the remainder of the way to the coastline, raining deadly fire in a desperate attempt to thwart the attack. Inside the B-17s every available man was positioned behind a belt-fed machinegun to defend his airplane.

In the nose of The Duchess, Lieutenant Mathis knelt at his station over the Norden bombsight to mark readings and make dial adjustments. Coolly went about his work despite a heavy barrage of flak that reached upward when the formation crossed the coastline.

"Flak hit our ship and sounded like hail on a roof," recalled navigator Jesse Elliott who manned his station directly behind the bombardier. "I glanced at Lt. Mathis who was crouched over his bombsight lining up the target. Jack was an easy-going guy and the flak didn't bother him. He wasn't saying a word--just sticking there over his bombsight, doing his job.

"'Bomb bay doors are open,' I heard Jack call up to the pilot, Captain Stouse. Then Jack gave instructions to climb a little more to reach bombing altitude."

Jack Mathis knew well that at the moment, he was the single most important job in the squadron. He refused to be deterred or distracted by anything. Only seconds from the release of the bombs the enemy reached out one more time to deny him success. A large explosion to the right of The Duchess peppered the bomber's nose with a hail of shrapnel. One large chunk of hot metal tore through the glass compartment where Mathis knelt at his controls.

"I saw Jack falling back toward me and threw up my arm to ward off the fall," Lieutenant Elliott later recalled. "By that time both of us were way back in the rear of the nose--blown back there, I guess, by the flak. I was sort of half-standing, half-lying against the back wall and Jack was leaning up against me. I didn't know he was injured at the time."

Indeed, Jack Mathis was seriously injured. Shell fragments had shattered his right arm nearly severing it above the elbow. A larger piece of metal tore a gaping hole in his side, his oxygen mask had been blown off his face, and his body slammed fully nine feet backward in by explosion. The man was virtually dead--and with The Duchess only seconds from its critical bomb-drop station. Somehow the dead bombardier did the impossible, summoning his last ounce of ebbing strength to maintain consciousness long enough to complete his mission.

"Without any assistance from me he pulled himself back to his bombsight," Elliott continued. "I looked at my watch to start timing the fall of the bombs. I heard Jack call out on the intercom, 'bombs....'. He usually called it out in a sort of singsong. But he never finished the phrase this time. The words just sort of trickled off, and I thought his throat mike had slipped out of the place, so I finished out the phrase 'bombs away' for him... I closed the bomb bay (doors) and returned to my station."

The minutes that followed remained dangerous while enemy fighters continued to attack the formation as The Duchess turned to head home. Behind her, the remaining bombers of the squadron noted the fall of the lead pilot's bombs and released their own in what later proved to be a deadly accurate series of explosions. After the war the director of the Bremen-Vulkan Vegesack submarine building shipyard recalled that 102 persons were killed, four submarines were damaged, and production was halted for two months. "The men who guided this raid did a good job," he remarked, never realizing that one of those all-important men had been virtually a dead man.

Meanwhile, with the wind screaming through the shattered nose of his Flying Fortress, Harold Stouse headed for home. "I was pretty busy at my guns there for a while," Staff Sergeant Eldon Audiss recalled in a recent telephone interview, "but as things settled down, I heard Stouse on the mike saying, 'Audiss, as soon as those damn fighters leave, get down and check on Mathis. I think he's in trouble."

Working his way forward, the airplane's flight engineer found The Duchess' nose compartment nearly destroyed. Broken glass still blew about in the rushing winds and Lieutenant Elliott, who had also been injured, was now seated at his navigator's table in shock. Jack Mathis was slumped silently over his bombsight.

"I rushed forward and found the gears were still turning and his harness was caught in them, pulling him forward. I grabbed my knife to cut him loose and pulled him back. I reached out toward the wound in his side and all four fingers slipped into the hole. I knew then that he was dead. What I'll never know is how he managed to get back to his bombsight and finish that mission."

Back at Molesworth Lieutenant Mark Mathis heard the sound of airplane engines, signaling the return of the Flying Fortresses. He rushed to the airfield and breathed a sigh of relief upon noting The Duchess was leading the way in. Then his heart leaped to his throat at the sight of a flare, the pilot's message to men on the ground that wounded was aboard. When the B-17 taxied in for a landing the damage to its nose was apparent, and Mark knew instantly that his brother was in trouble. He followed the ambulance to the hospital where Jack Mathis was pronounced dead.

Father Edmond Skoner joined Mark in his sad journey to the mortuary and offered what comfort he could while the older brother wept over Jack's body. Between those tears, he swore an oath before the 303rd Bomb Group chaplain that he would avenge his brother's death.

Mark's subsequent request for a transfer to the 303rd was approved and he flew his first mission with the 359th Bombardment Squadron on April 17, 1943. On that mission, Mark Mathis was a member of Captain Stouse's crew in The Duchess. Kneeling over the same battle-scarred bombsight his brother had used one month earlier, he accurately placed his bombs on the Fock Wulf Factory in Bremen, not far from where his brother had dropped his final payload.

Soon thereafter the crew of The Duchess returned home to train new aircrews; they were after all, one of the most experienced bomber crews still alive. Mark might well have returned with the crew but requested to remain in England to fly his full twenty-five missions. "Mark was absolutely a great guy," recalled Donald Richardson who was a radioman on The Duchess for both Jack's last mission and Mark's first mission. "Unfortunately, that was the only mission on which I flew with him," he added in a recent interview.

His second mission was with the 427th Bombardment Squadron in an unnamed airplane on a flight over Antwerp, Belgium. Upon his return to Molesworth, Mark Mathis received a permanent assignment to Captain Ross Bales' crew in FDR's Potato Peeler Kids.

On May 13, Mark flew his third mission, now with Captain Bales, to successfully bomb Potes Aircraft Factory in Meaulte, France. The very next day FDR's Potato Peeler Kids flew again, this time over the dangerous North Sea to attack Kiel, Germany. The formation was hit by a deadly hail of gunfire from 100 - 150 enemy fighters but continued bravely on to the target. Every Week Magazine later published perhaps the best account of the tragedy that occurred on the return flight home:

"Mark Mathis' bombs had fallen squarely on the aiming point in Kiel as strike photos later proved. The FDR was badly hit on the elevator and began to struggle as the formation came off the target. The yellowness of Marshal Goering's crack fighter squadron, 'The Abbeville Gang' or 'Herman's Pets' as the B-17 men called them, began to flirt with the idea of going for the FDR.

"Bill Calhoun disobeyed common sense and pulled his squadron back to cover the FDR. The ship was hit but it was going strong--just a little slower than the rest. There were no Aldis Lamp signals from FDR, so Calhoun believed the ship had a good chance. FDR began losing altitude off the coast of Europe. Out of the clouds came the yellow noses and knocked out two engines! The gunners were still blazing away at the attacking FW-190s when the order to bail out was evidently given.

Major Calhoun, who one month earlier had written Avis Mathis to advise her of the loss of her son, left the cockpit to follow the plight of the falling FDR's Potato Peeler Kids for as long as possible. Hope was buoyed by the sight of six or seven parachutes shortly before the Flying Fortress crashed into the sea. Despite that initial optimistic glimpse, within days the C.O. found himself writing his second letter to Avis Mathis.

Officially, Mark Mathis was listed as Missing in Action for one year. No word of the fate of Captain Bales or his crew was ever heard, however, and in 1944 Mark Mathis was officially declared Killed in Action.

For his last mission, Jack Mathis was posthumously awarded an Oak Leaf Cluster for his earlier Air Medal. Mark too, earned a posthumous Air Medal for his own service.

The tragedy of the Mathis brothers became legendary throughout the Army Air Force, overshadowed  only the accounts of their heroism and dedication to defending their country. On September 21, 1943, at Goodfellow Field back in San Angelo, Texas, Major General Barton K. Yount presented Avis Mathis with the Medal of Honor earned by her son. At that moment Lieutenant Jack Mathis became the first airman to receive his nation's highest honor for an air mission over Europe.

only the accounts of their heroism and dedication to defending their country. On September 21, 1943, at Goodfellow Field back in San Angelo, Texas, Major General Barton K. Yount presented Avis Mathis with the Medal of Honor earned by her son. At that moment Lieutenant Jack Mathis became the first airman to receive his nation's highest honor for an air mission over Europe.

Avis Mathis passed away in San Angelo, Texas, in 1961. Rhude Mark Mathis, Sr., returned to Texas where he died in 1965, leaving only the couple's youngest son, Harrell Clegg Mathis, to preserve the story of the Bombardier Brothers. On May 12, 1989, the sole-surviving Mathis brother turned preservation of that legacy, along with his two brothers' medals, over to the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio. Joining him that day for a moving ceremony were his three sons, Mark Mathis, Jack Mathis, and David Mathis.

More than half a century after the end of World War II, passengers flying into or out of San Angelo, Texas, must pass through the corridors of Mathis Airport. Hanging in the hallway is a photo of two World War II airmen and a plaque denoting their service. They are the Mathis Brothers.

Indeed, as General John J. Pershing stated at the close of the First World War:

"Time will not dim the glory of their deeds."

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mr. Eldon Audiss for the reconstruction of this story. As a staff sergeant in 1942-43, Mr. Audiss was an engineer on The Duchess. Faithfully he kept the bomb rings of each of his missions and, half a century later can accurately recall the order of events by their number. Mr. Audiss needs nothing to recall the last mission of Jack Mathis, it is an event beyond ever forgetting.

Many of these details and photographs would not be available if not for the sincere efforts of the Mathis family. Jack and Mark Mathis' cousin John Mathis, and their second cousin Fred Mathis have spent years working to research and preserve the story of the Mathis Brothers.

Sources

Firsbee, John L. "A Tale of Two Texans", Air Force Valor, Vol. 69, No. 3, March 1986

Humphreys, Ned, "The Mathis Brothers", Crosshairs Magazine, June 1989

Mathis, John, Personal Papers and Mathis Family History

Wolk, Herman S., "Decision at Casablanca", Air Force Magazine, Vol. 86, No. 1, January 2003

Interviews

Audiss, Eldon. Telephone interview with author, September 8, 2003

Richardson, Donald. Telephone interview with author, September 5, 2003

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Ira C. Eaker, USAAF

Ira C. Eaker, USAAF