The Four Chaplains

Written by C. Douglas Sterner

Brotherhood has nothing to do with the similarities between men. Even among twins, no two brothers are exactly alike. These differences can create challenges to family harmony, incite jealousy, and lead to sibling rivalries. At the same time, it is these differences that make a family stronger, better-rounded, and best-equipped to face the challenges of life. In times of crisis, when a family pulls together, these differences make it possible to approach a problem from different perspectives and find solutions for the common good. There is strength in diversity, and perhaps a family should rejoice more in the differences between brothers and sisters than in the things they share in common.

Brotherhood has nothing to do with the similarities between men. Even among twins, no two brothers are exactly alike. These differences can create challenges to family harmony, incite jealousy, and lead to sibling rivalries. At the same time, it is these differences that make a family stronger, better-rounded, and best-equipped to face the challenges of life. In times of crisis, when a family pulls together, these differences make it possible to approach a problem from different perspectives and find solutions for the common good. There is strength in diversity, and perhaps a family should rejoice more in the differences between brothers and sisters than in the things they share in common.

In November 1942, four young men "found each other" while attending Chaplain's School at Harvard University. They had enough in common to bond them together. At age 42, George Fox was the "older brother". The youngest was 30-year-old Clark Poling, and less than three years separated him from the other two, Alexander Goode and John Washington. A common cause brought them together, the desire to render service to their Nation during the critical years of World War II.

Between the early days of May to late July, the four had entered military service from different areas of the country. Reverend Fox enlisted in the Army from Vermont the same day his 18-year old son Wyatt enlisted in the Marine Corps. During World War I, though only 17 years old, Fox had convinced the Army he was actually 18 and enlisted as a medical corps assistant. His courage on the battlefield earned him the Silver Star, the Croix de Guerre, and the Purple Heart. When World War II broke out he said, "I've got to go. I know from experience what our boys are about to face. They need me." This time, however, he didn't enlist to heal the wounds of the body. As a minister, he was joining the Chaplains Corps to heal the wounds of the soul.

Reverend Clark V. Poling was from Ohio and pastoring in New York when World War II threatened world freedom. He determined to enter the Army, but not as a chaplain. "I'm not going to hide behind the church in some safe office out of the firing line," he told his father when he informed him of his plans to serve his country. His father, Reverend Daniel Poling knew something of war, having served as a chaplain himself during World War I. He told his son, "Don't you know that chaplains have the highest mortality rate of all? As a chaplain, you'll have the best chance in the world to be killed. You just can't carry a gun to kill anyone yourself." With a new appreciation for the role of the Chaplains Corps, Clark Poling accepted a commission and followed in his father's footsteps.

Like Clark Poling, Alexander Goode had followed the steps of his own father in ministry. His first years of service were in Marion, Indiana; then he moved on to York, Pennsylvania. While studying and preparing to minister to the needs of others, "Alex" had joined the National Guard. Ten months before Pearl Harbor he sought an assignment in the Navy's Chaplains Corps but wasn't initially accepted. When the war was declared, he wanted more than ever to serve the needs of those who went in harm's way to defend freedom and human dignity. He chose to do so as a U.S. Army Chaplain.

One look at the be-speckled, mild-mannered John P. Washington, would have left one with the impression that he was not the sort of man to go to war and become a hero. His love of music and beautiful voice belied the toughness inside. One of nine children in an Irish immigrant family living in the toughest part of Newark, New Jersey, he had learned through sheer determination to hold his own in any fight. By the time he was a teenager, he was the leader of the South Twelfth Street Gang. Then God called him to ministry, returning him to the streets of New Jersey to organize sports teams, play ball with young boys who needed a strong friend to look up to and inspire others with his beautiful hymns of praise and thanksgiving.

Upon meeting at the Chaplains' school, the four men quickly became friends. One of Clark Poling's cousins later said, "They were all very sociable guys, who seemed to have initiated interfaith activities even before the war. They hit it off well at chaplains' school. Sharing their faith was not just a first-time deal for them. They were really very close. They had prayed together a number of times before that final crisis." (Reverend David Poling)

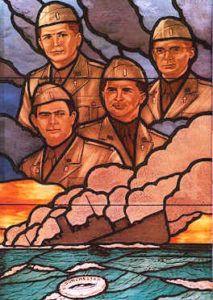

The observation pointed out by Clark's cousin is of note, for the men of whom he spoke were unique. Their close bond might easily have marked them as "The Four Chaplains" long before a fateful night three months after they first met when their actions would forever make the title synonymous with the names of George L. Fox, Alexander D. Goode, Clark V. Poling, and John P. Washington. The differences in their backgrounds and personalities could have been easily outweighed by their common calling to ministry, had it not been for one major difference: Reverend Fox was a Methodist Minister, Reverend Poling was a Dutch Reformed Minister, Father Washington was a Catholic Priest, and Rabbi Goode was Jewish.

The observation pointed out by Clark's cousin is of note, for the men of whom he spoke were unique. Their close bond might easily have marked them as "The Four Chaplains" long before a fateful night three months after they first met when their actions would forever make the title synonymous with the names of George L. Fox, Alexander D. Goode, Clark V. Poling, and John P. Washington. The differences in their backgrounds and personalities could have been easily outweighed by their common calling to ministry, had it not been for one major difference: Reverend Fox was a Methodist Minister, Reverend Poling was a Dutch Reformed Minister, Father Washington was a Catholic Priest, and Rabbi Goode was Jewish.

In a world where differences have all too often created conflict and separated brothers, the Four Chaplains found a special kind of unity, and in that unity they found strength. Despite the differences, they became "brothers" for they had one unseen characteristic in common that overshadowed everything else. They were brothers because all four shared the same father.

U.S.A.T. Dorchester

The U.S.A.T. Dorchester was an aging, luxury coastal liner that was no longer luxurious. In the nearly four years from December 7, 1941, to September 2, 1945, more than 16 million American men and women were called upon to defend human dignity and freedom on two fronts, in Europe and the Pacific. Moving so large a force to the battlefields was a monumental effort, and every available ship was being pressed into service. Some of these were converted into vessels of war, others to carrying critical supplies to the men and women in the field. The Dorchester was designated to be a transport ship. All non-critical amenities were removed and cots were crammed into every available space. The intent was to get as many young fighting men as possible on each voyage. When the soldiers boarded in New York on January 23, 1943, the Dorchester certainly was filled to capacity. In addition to the Merchant Marine crew and a few civilians, young soldiers filled every available space. There were 902 lives about to be cast to the mercy of the frigid North Atlantic.

As Dorchester left New York for an Army base in Greenland, many dangers lay ahead. The sea itself was always dangerous, especially in this area known for ice flows, raging waters, and gale-force winds. The greatest danger, however, was the ever-present threat of German submarines, which had recently been sinking Allied ships at the rate of 100 every month. The Dorchester would be sailing through an area that had become infamous as "Torpedo Junction".

Most of the men who boarded for the trip were young, frightened soldiers. Many were going to sea for the first time and suffered sea-sickness for days. They were packed head to toe below deck, a steaming human sea of fear and uncertainty. Even if they survived the eventual Atlantic crossing, they had nothing to look forward to, only the prospects of being thrown into the cauldron of war on foreign shores. They were men in need of a strong shoulder to lean on, a firm voice to encourage them, and a ray of hope in a world of despair. In their midst moved four men, Army Chaplains, called to put aside their own fears and uncertainties to minister to the needs of others.

Perhaps Chaplain Fox thought of his own 18-year-old son, serving in the Marine Corps, as he walked among the young soldiers on the Dorchester, giving strength and Spiritual hope to those he could. Before leaving he had said goodbye to his wife and 7-year-old daughter Mary Elizabeth. It was Chaplain Fox's second war, for the first world war, the "war to end all wars," had not done so.

In other parts of the ship Father Washington likewise did his best to soothe the fears of those about him. As a Catholic Priest, he was single and hadn't left behind a wife or children, but there were eight brothers and sisters at home to fear for him and pray for his safety. Now his closest brothers were the other three Chaplains on the Dorchester. They leaned on each other for strength, as they tried daily to mete that strength out to others. Surely as he prayed for his make-shift parish, Father Washington also whispered a prayer for Chaplain Fox, Chaplain Poling, and Rabbi Goode. Not only had Chaplain Fox left a son and daughter behind, but Rabbi Goode had also left behind a loving wife and 3-year-old daughter. Chaplain Poling's son Corky was still an infant, and within a month or two, his wife would be giving birth to their second child. In times of war, perhaps being single had its advantages.

With so many men crammed into so small of a space, all of them so much in need of the ray of hope Spiritual guidance could afford, differences ceased to be important. All of the soldiers shared the same level of misery and fear, whether Protestant, Catholic, or Jew. The title "Rabbi", "Father", or "Reverend" was of little consequence when a man needed a Chaplain. A prayer from Rabbi Goode could give strength to the Catholic soldier as quickly as a hymn from the beautiful voice of Father Washington could warm the heart of a Protestant. The Jewish soldier facing an uncertain future on foreign shores could draw on the strength of a Protestant to help him face tomorrow. When sinking in the quicksand of life one doesn't ask for the credentials of he who offers the hand of hope, he simply thanks God that the helping hand is there.

The crossing was filled with long hours of boredom and misery. Outside, the chilly Arctic winds and cold ocean spray-coated Dorchester's deck with ice. Below deck, the soldiers' quarters were hot from too many bodies, crammed into too small a place, for too many days in a row. Finally, on February 2nd, the Dorchester was within 150 miles of Greenland. It would have generated a great sense of relief among the young soldiers crowded in the ship's berths, had not the welcomed news been tempered by other news of grave concern. One of Dorchester's three Coast Guard escorts had received sonar readings during the day, indicating the presence of an enemy submarine in a place known as "Torpedo Junction".

Hans Danielson, the Dorchester's captain, listened to the news with great concern. His cargo of human lives had been at sea for ten days and was finally nearing its destination. If he could make it through the night, air cover would arrive with daylight to safely guide his ship home. The problem would be surviving the night. Aware of the potential for disaster, he instructed the soldiers to sleep in their clothes and life jackets just in case. Below deck, however, it was hot and sweaty as too many bodies lay down, closely packed in the cramped quarters. Many of the men, confident that tomorrow would dawn without incident, elected to sleep in their underwear. The life jackets were also hot and bulky, so many men set them aside as an unnecessary inconvenience.

Outside it was another cold, windy night as the midnight hour signaled the passing of February 2nd and the beginning of a new day. In the distance, a cold, metal arm broke the surface of the stormy seas. At the end of that arm, a German U-Boat (submarine) captain monitored the slowly passing troop transport. Shortly before one in the morning, he gave the command to fire.

A Test of Faith

Quiet moments passed as silent death reached out for the men of the Dorchester, then the early morning hours of February 3, 1943, were shattered by the flash of a blinding explosion and the roar of massive destruction. The hit had been dead-on, tossing men from their cots with the force of its explosion. A second torpedo followed the first, instantly killing 100 men in the hull of the ship. Power was knocked out by the explosion in the engine room, and darkness engulfed the frightened men below deck as water rushed through gaping wounds in Dorchester's hull. The ship tilted at an unnatural angle as it began to sink rapidly, and piles of clothing and life jackets were tossed about in the darkness where no one would ever find them. Wounded men cried out in pain, frightened survivors screamed in terror, and all groped frantically in the darkness for exits they couldn't find. Somewhere in that living hell, four voices of calm began to speak words of comfort, seeking to bring order to panic and bedlam. Slowly soldiers began to find their way to the deck of the ship, many still in their underwear, where they were confronted by the cold winds blowing down from the arctic. Petty Officer John J. Mahoney, reeling from the cold, headed back towards his cabin. "Where are you going?" a voice of calm in the sea of distress asked?

"To get my gloves," Mahoney replied.

"Here, take these," said Rabbi Goode as he handed a pair of gloves to the young officer who would never have survived the trip to his cabin and then back to safety.

"I can't take those gloves," Mahoney replied.

"Never mind," the Rabbi responded. "I have two pairs." Mahoney slipped the gloves over his hands and returned to the frigid deck, never stopping to ponder until later when he had reached safety, that there was no way Rabbi Goode would have been carrying a spare set of gloves. As that thought finally dawned on him he came to a new understanding of what was transpiring in the mind of the fearless Chaplain. Somehow, Rabbi Goode suspected that he would himself, never leave the Dorchester alive.

Before boarding the Dorchester back in January, Reverend Poling had asked his father to pray for him, "Not for my safe return, that wouldn't be fair. Just pray that I shall do my duty...never be a coward...and have the strength, courage, and understanding of men. Just pray that I shall be adequate." He probably never dreamed that his prayer request would be answered so fully. As he guided the frightened soldiers to their only hope of safety from the rapidly sinking transport, he spoke calm words of encouragement, urging them not to give up. In the dark hull of the Dorchester, he was more than adequate; He was a hero.

Likewise, Reverend Fox and Father Washington stood out within the confines of unimaginable hell. Wounded and dying soldiers were ushered into eternity to the sounds of comforting words from men of God more intent on the needs of others, than on their own safety and survival. Somehow, by their valiant efforts, the Chaplains succeeded in getting many of the soldiers out of the hold and onto Dorchester's slippery deck.

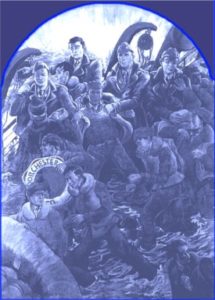

In the chaos around them, lifeboats floated away before men could board them. Others capsized as panic continued to shadow reason and soldiers loaded the small craft beyond the limit. The strength, calm, and organization of the Chaplains had been so critical in the dark hull. Now, on deck, they found that their mission had not been fully accomplished. They organized the effort, directed men to safety, and left them with parting words of encouragement. In little more than twenty minutes, the Dorchester was almost gone. Icy waves broke over the railing, tossing men into the sea, many of them without life jackets. In the last moments of the transport's existence, the Chaplains were too occupied opening lockers to pass out life jackets to note the threat to their own lives.

In less than half an hour, water was beginning to flow across the deck of the sinking Dorchester. Working against time the Chaplains continued to pass out the life vests from the lockers as the soldiers pressed forward in a ragged line. And then....the lockers were all empty...the life jackets were gone. Those still pressing in line began to realize they were doomed, there was no hope. And then something amazing happened, something those who were there would never forget. All Four Chaplains began taking their own life jackets off and putting them on the men around them. Together they sacrificed their last shred of hope for survival, to ensure the survival of other men, most of them total strangers. Then time ran out. The Chaplains had done all they could for those who would survive, and nothing more could be done for the remaining, including themselves.

In less than half an hour, water was beginning to flow across the deck of the sinking Dorchester. Working against time the Chaplains continued to pass out the life vests from the lockers as the soldiers pressed forward in a ragged line. And then....the lockers were all empty...the life jackets were gone. Those still pressing in line began to realize they were doomed, there was no hope. And then something amazing happened, something those who were there would never forget. All Four Chaplains began taking their own life jackets off and putting them on the men around them. Together they sacrificed their last shred of hope for survival, to ensure the survival of other men, most of them total strangers. Then time ran out. The Chaplains had done all they could for those who would survive, and nothing more could be done for the remaining, including themselves.

This Side of Heaven

Those who had been fortunate enough to reach lifeboats struggled to distance themselves from the sinking ship, lest they be pulled beneath the ocean swells by the chasm created as the transport slipped into a watery grave. Then, amid the screams of pain and horror that permeated the cold dark night, they heard the strong voices of the Chaplains. "Shma Yisroel Adonai Elohenu Adonai Echod." "Our Father, which art in Heaven, Hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done."

Looking back they saw the slanting deck of the Dorchester, its demise almost complete. Braced against the railings were the Four Chaplains, praying, singing, giving strength to others by their final valiant declaration of faith. Their arms were linked together as they braced against the railing and leaned into each other for support, Reverend Fox, Rabbi Goode, Reverend Poling, and Father Washington. Said one of the survivors, "It was the finest thing I have ever seen this side of heaven."

Looking back they saw the slanting deck of the Dorchester, its demise almost complete. Braced against the railings were the Four Chaplains, praying, singing, giving strength to others by their final valiant declaration of faith. Their arms were linked together as they braced against the railing and leaned into each other for support, Reverend Fox, Rabbi Goode, Reverend Poling, and Father Washington. Said one of the survivors, "It was the finest thing I have ever seen this side of heaven."

And then, only 27 minutes after the first torpedo struck, the last vestige of the U.S.A.T. Dorchester disappeared beneath the cold North Atlantic waters. In its death throes, it reached out to claim any survivors nearby, taking with it to its grave the four ministers of different faiths who learned to find strength in their diversity by focusing on the Father they shared. On that day, they Made their "Father" very proud.

Of the 920 men who left New York on the U.S.A.T. Dorchester on January 23rd, only 230 were plucked from the icy waters by rescue craft. In addition to the Four Chaplains, 668 other men went to a watery grave with the ship. Had it not been for the Chaplains, the number of dead would certainly have been much higher.

On May 28, 1948, the United States Postal Service issued a special stamp to commemorate the brotherhood, service, and sacrifice of the Four Chaplains.

On May 28, 1948, the United States Postal Service issued a special stamp to commemorate the brotherhood, service, and sacrifice of the Four Chaplains.

On July 14, 1960, by Act of Congress (Public Law 86-656, 86th Congress), the United States Congress authorized the "Four Chaplains Medal". The Star of David, Tablets of Moses, and Christian Cross are shown in relief on the back of the medal, along with the inscribed names of all four heroic Chaplains.

On July 14, 1960, by Act of Congress (Public Law 86-656, 86th Congress), the United States Congress authorized the "Four Chaplains Medal". The Star of David, Tablets of Moses, and Christian Cross are shown in relief on the back of the medal, along with the inscribed names of all four heroic Chaplains.

On January 18, 1961, Secretary of the Army Wilbur M. Brucker presented the award posthumously to the families of the Four Chaplains at Fort Myer, Virginia.

The Chapel of the Four Chaplains became one of the most enduring tributes to Reverend Fox, Rabbi Goode, Reverend Poling, and Father Washington. Time has dimmed the memory of the four great men, and with that fading memory, the chapel itself has slipped into the background of the American conscience.

The Chapel of the Four Chaplains became one of the most enduring tributes to Reverend Fox, Rabbi Goode, Reverend Poling, and Father Washington. Time has dimmed the memory of the four great men, and with that fading memory, the chapel itself has slipped into the background of the American conscience.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED