When Heroes Filled The Sky

Addison Baker, Lloyd Hughes, John Jerstead, Leon Johnson, and John Kane

"If nobody comes back...the results will be worth the cost!

Brigadier General Uzal Ent

In the Pacific, American airmen had been at war for eighteen months, dating their combat actions from the opening battles in the Philippines on December 7-8, 1941. Subsequently activated as General George Kenney's 5th Air Force eight months into the war, Ken's Men (and their predecessors before the 5th was established) made history in the Battle of Midway, The Coral Sea, The Bismarck Sea, and others. These airmen were instrumental in turning back the Japanese offensive in New Guinea and supporting the Marines in the ouster of the enemy at Guadalcanal. In their first twelve months of combat operations, Ken's Men netted four Medals of Honor for their heroism in the Pacific theater. Their heroic defense in the Pacific had also given new hope to the American public back home.

Little Blitz Week, the late July 1943 massive bombing campaign launched out of Britain by the U.S. Army's 8th Air Force, ended just seventeen days before the now-famous Mighty Eighth marked its first anniversary of combat operations. In the nearly twelve-month period General Ira Eaker's airmen had netted three of the ten Medals of Honor earned by members of the U.S. Army Air Force.

Little Blitz Week, the late July 1943 massive bombing campaign launched out of Britain by the U.S. Army's 8th Air Force, ended just seventeen days before the now-famous Mighty Eighth marked its first anniversary of combat operations. In the nearly twelve-month period General Ira Eaker's airmen had netted three of the ten Medals of Honor earned by members of the U.S. Army Air Force.

For both the 5th and the 8th, the first year of combat operations had been a process of trial-and-error in the development of aerial tactics. Never before in history had the airplane, still less than 40 years old, been employed so heavily in warfare. In Europe General Eaker's pilots in their B-17 Flying Fortresses were proving the validity of high-altitude, daylight bombing. In the Pacific General Kenney's bombers flew both daylight and night bombing missions against Japanese installations, usually from altitudes over 12,000 feet. Experiments with skip bombing led to frequent low-level operations for Kenney's bomber fleet, but the prevailing doctrine of aerial warfare for United States air operations remained the concept of high-altitude bombardment.

Of the eight Medals of Honor awarded for air operations through the end of July 1943 (two airmen received awards for ground operations), all but one had been awarded for heroism in high-altitude missions flown in B-17 Flying Fortresses. The only exception had been Jimmy Doolittle's low-level, surprise raid over Tokyo in B-25 Mitchell bombers in April 1942.

Of the eight Medals of Honor awarded for air operations through the end of July 1943 (two airmen received awards for ground operations), all but one had been awarded for heroism in high-altitude missions flown in B-17 Flying Fortresses. The only exception had been Jimmy Doolittle's low-level, surprise raid over Tokyo in B-25 Mitchell bombers in April 1942.

The B-17 Flying Fortress was the darling of the US Army Air Force in the early days of World War II. The heavily armed bomber could fly long-range missions deep into enemy territory, stave off waves of opposing fighters, endure punishing anti-aircraft damage, accurately drop bombs five miles above its target, and return safely home. Indeed, by the end of World War II, of the thirty-six Medals of Honor awarded for air operations, seventeen were awarded to pilots or crewmen flying in B-17s, double that of any other airplane.

But the Flying Fortress was not without competition.

The B-24 Liberator

Early in 1938 at the direction of President Roosevelt, the Army Air Corps called for a bomber design that would provide a larger payload and longer range than the B-17. The result was the XB-24, delivered the following year by Consolidated Aircraft Company in San Diego, California. The new bomber featured a high aspect ratio wing design sold to Consolidated in 1937 by David R. Davis, a near-destitute inventor. It was enhanced with Fowler wing flaps, the first tricycle landing gear on a heavy bomber, and twin tails.

Initial wind tunnel tests confirmed the improved performance of the Davis wing design and in February 1939, the U.S. Army Air Corps issued a Type Specification to cover the Consolidated design. After allowing nominal time for other manufacturers to submit their own plans, a contract to build the XB-24 was signed on March 30, 1939.

The resulting aircraft that became known as the B-24 Liberator had a range of 2,850 miles and could carry a maximum load of 8,000 pounds of bombs. It could fly faster and farther than the Flying Fortress, and deliver a greater bomb load. The B-24's enhanced performance aside, early versions of the workhorse bomber lacked firepower, power-operated turrets, and sufficient protection for the crew. Also devoid of the trim look of the vaunted B-17, American airmen sarcastically called the new bomber the "Pregnant Cow".

France placed an order with Consolidated for B-24s in May 1940, but when the Germans entered and occupied France a month later, this order was diverted to England to supply a long-range bomber for the Royal Air Force.

British pilots were similarly not impressed. Desperate for any aircraft, however, they welcomed the arrival of the first B-24s (designated LB-30s). Rather than employing them as a high-altitude, long-range bomber, however, the R.A.F. primarily used the new four-engine aircraft for low-level anti-submarine patrols off the island nation's vulnerable coastline. Most early R.A.F. long-range bombing missions were flown in the equally unpopular American-built B-17Cs, called the Fortress I.

After Pearl Harbor, and the United States declaration of war against Germany and Italy three days following, Britain's leadership began impatiently awaiting the arrival of American bombers and pilots. Command elements of the 8th Air Force started arriving in the spring and the first American bomber, a B-17E Flying Fortress, landed at Prestwick Airfield in England on July 1. Seven weeks later on August 17, Colonel Frank K. Armstrong led a dozen Flying Fortresses of the 97th Bomb Group to strike enemy targets from 23,000 feet over Rouen, in occupied France. That flight marked the first mission of the Eighth Air Force, though weeks earlier there had been a more highly publicized--and propagandized--first American mission over Europe.

History records that the first American bombing mission over Europe occurred as the result of an ill-advised promise General Hap Arnold made to Prime Minister Winston Churchill on May 30, 1942. The Prime Minister was impatient with the slow building of an American air force to join the R.A.F. in the campaign against Hitler. Realizing that the 97th was getting ready to move to England within weeks, at that late-May meeting Hap told Churchill, "We will be fighting with you on July 4th."

The date for the first American bombing raid over Fortress Europe had been selected for its significance in American history, an irony that the British might well have not appreciated were they not desperate for allies in the war against Hitler. As the date neared, however, it was apparent that the 8th Air Force would not be able to field a large formation of heavy bombers to penetrate enemy territory at a high altitude and wreak destruction with a payload of bombs accurately targeted using in the top-secret Norden bombsight. On July 3 an officer with the 8th Air Force noted the arrival of B-17E #19085 two days earlier in the strategic air arms' table of equipment: "Arrival of Aircraft: B-17E, Total: 1."

To fulfill General Arnold's promise to Churchill, General Eaker assigned the first American mission to the 15th Bombardment Squadron that had arrived in mid-May. The unit had no heavy bombers and, in fact, was flying twin-engine Douglas A-20 (attack) planes that belonged to the R.A.F. The Brits called Bostons.

When radio and newspapers announced the following day that the first American bombs had fallen on Europe the reports were highly misleading. In fact, the mission had been a joint mission flown by a dozen R.A.F. Bostons, six of which were crewed by American airmen. The mission was not the massive, high-altitude raid for which the Mighty Eighth would eventually become famous--it employed none of the strategy defined by AWPD-1 which was the basis of American Air Force doctrine.

Furthermore, the simple idea that the Independence Day mission was the First American raid on Europe was false. Known only to a few at that time, and almost lost to history today, is the fact that more than two weeks earlier American crews based in Egypt had flown a daring raid against an obscure target in Romania. The first American bombs to fall on Europe came not from the bomb bays of Eighth Air Force Flying Fortresses but from the bellies of an unassigned, top-secret group of free-booting airmen flying B-24 Liberators.

Halpro: The Halverson Project

Halpro (The Halverson Project) was planned in January 1942, within a month of the attack at Pearl Harbor. Initially, it was designed to be a sequel to the most famous bombing mission of World War II, the Doolittle raid over Tokyo. The rapid movement of the Japanese offensive in China, however, changed Halpro's mission, and through a strange series of circumstances, the project would become the prequel to what might well have been the second most famous bombing raid of the war.

Halpro (The Halverson Project) was planned in January 1942, within a month of the attack at Pearl Harbor. Initially, it was designed to be a sequel to the most famous bombing mission of World War II, the Doolittle raid over Tokyo. The rapid movement of the Japanese offensive in China, however, changed Halpro's mission, and through a strange series of circumstances, the project would become the prequel to what might well have been the second most famous bombing raid of the war.

In the first month after the United States entered World War II, the Air War Plans Division put forth a plan to establish a major fighting air command in Burma to turn back the Japanese' sweeping advance into China. That new command was to be designated the 10th Air Force, and in mid-January Operation Aquila was employed to begin the initial buildup necessary to establish that command.

Operation Aquila was a 5-point program designed to provide fighters, bombers, and a supply chain to the theater. The first three points established the fighter command and logistics:

• The supply requisite was to take the form of thirty-five DC-3 transports flown into the region.

• Fighters to augment Claire Chennault's AVG Flying Tigers were to be sent in the form of fifty-one P40Es to be assembled in West Africa and flown to China.

• Thirty-three factory-fresh A-20 attack planes under the command of Colonel Leo H. Dawson were to be transported to the Chinese air force under the lend-lease agreement, after which the pilots were to be assigned to the 10th Air Force.

The bomber element of the new 10th Air Force was to originate from two separate, highly secret projects.

• The first was a volunteer group of B-25 pilots under command of Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle. The twenty-six medium-range bombers were tasked with making a carrier-borne assault on Tokyo in what would become Doolittle's famous Tokyo Raid. Theirs was a two-part mission. After making the historic attack on the Japanese capital, the raiders were to fly to China where pilots, crews, and their B-25s were to be absorbed by the 10th Air Force. (It was the loss of all 26 bombers that distressed Doolittle to the belief that he would be court-martialed, despite the success of the first part of his mission.)

• Long-range bombing missions in the China-Burma theater would be carried out by a group of twenty-three B-24s under the command of Colonel Halvor "Hurry-up Harry" Halverson. This was the element that became known, by those few planners aware of its existence, as the Halpro Group (Halverson Project.) The group was tasked with flying east to reach China after the completion of the Doolittle Raid. From their airfields in China, the Liberators would be within bombing range of Tokyo and able to continue the work from the west of Japan, that Doolittle's men started from an aircraft carrier east of the islands.

On February 12 while Doolittle was putting together his own volunteer crew, the 10th Air Force was activated at Patterson Field, Fairfield, Ohio. Five days later Colonel Harry A. Halverson was appointed the first Commanding Officer of the 10th Air Force. During March the Headquarters of the 10th was shifted from the U.S. to India after Major General Lewis H. Brereton, who had arrived in India from the Netherlands East Indies, assumed command. The move began on March 8th and was expected to take a month. At the time of the change of command, the 10th had eight tactical aircraft at its disposal, all of the B-17s.

Meanwhile, Colonel Halverson began putting together his own unusual crew of airmen to pilot the twenty-three, factory-fresh B-24s to China. Only weeks after Doolittle's April 16 mission, the pilots of Halpro flew out of Florida. Their secretive sojourn to China took them south to Brazil before an eastward leg across the South Atlantic to Africa. From there the bombers flew to the Sudanese capital of Khartoum, just beyond the range of the daily Axis raids on R.A.F. bases in Egypt.

Halpro's last leg was to have been the flight into Chekiang, China, from which they hoped to bomb Tokyo. On May 11 the Japanese launched a major offensive in Chekiang. By the time Halpro reached Sudan the airfield in their intended area of operation had fallen. With nowhere to go Colonel Halverson put his pilots and crews into a series of training missions while awaiting further orders.

Ploesti

When Hitler began his blitzkrieg in Europe the small nation of Romania found itself precariously perched between German advances in Poland and Hungary and Soviet advances from Ukraine. The small country, not even as large as the state of Oregon, found itself besieged on two fronts despite attempts at neutrality.

When Hitler began his blitzkrieg in Europe the small nation of Romania found itself precariously perched between German advances in Poland and Hungary and Soviet advances from Ukraine. The small country, not even as large as the state of Oregon, found itself besieged on two fronts despite attempts at neutrality.

By ultimatum notes, on June 26 and 28, 1940, the Soviet Union forced Romania to cede Bessarabia, which had shaken off the Russian yoke in 1918, as well as Northern Bucovina (which had never belonged to Russia). Under the Vienna Diktat of August 30 that same year and after a German-Italia ultimatum, Romania was forced to give Hungary the north-western part of Transylvania. Under the Treaty of Craiova on September 7, 1940, Romania surrendered the southern part of Dobrudja. The loss of about one-third of the country's area and population caused a serious crisis which resulted in the abdication of King Carol II in favor of his son Mihai and the subsequent rise to power of General Ion Antonescu.

In June 1941 Romania abandoned neutrality and joined the Axis, primarily in hopes of regaining Basarabia and Northern Bucovina. Ironically, Romania had been allied AGAINST Germany in the First World War. In desperation now, she joined the Axis for reasons of self-preservation. Britain declared war on Romania (along with Finland and Hungary) on December 5, 1941.

The United States left its own initial policy of non-belligerency in the European war on December 11, 1941, four days after Pearl Harbor and three days after declaring war on Japan. It was not, however, until June 5, 1942, that the United States expanded that declaration of war on Germany and Italy to include Romania (along with Hungary and Bulgaria.) It was fateful timing, with Halpro impatiently awaiting new orders after the loss of its primary mission. When that order came it was almost as unbelievable as the circumstances that had brought Hurry-Up Harry Halverson's airmen to this point. Halpro's new orders were:

"Bomb Ploesti!"

Ploesti was an oil boom city in the plains below the Transylvanian Alps in the North and the Romanian capital of Bucharest in the south. Commercial refinement of oil began in Ploesti in 1857, making it the first city in the world to tap the riches of the earth that would become critical to feeding advancing technology including automobiles and then aircraft. By 1942 the refineries at Ploesti were producing nearly a million tons of oil a month, accounting for 40 percent of Romania's total exports. Most of that oil, as well as the highest-quality 90-octane aviation fuel in Europe, went to the Axis war effort. Ploesti provided nearly a third of the petrol that fueled Hitler's tanks, battleships, submarines, and aircraft. In return, Germany occupied Romania and protected her natural resources--more specifically, German gunners guarded the multiple refining and storage plants that ringed Ploesti.

Unlike the sequel to the first mission over Ploesti, an August 1943 raid that was planned for nearly a year and practiced for months, Halpro's mission was a target of opportunity raid afforded by the week-old declaration of war on Romania. The pre-mission briefing was short, simple, and laid out an impossible task. Halverson's B-24s were to fly out of Egypt in the dark of night, cross the Mediterranean to a point on the Turkish coast, and then circle that neutral nation to come in over German-occupied Greece. "You are not--I repeat not," advised the mission briefing officer from the R.A.F., "to enter neutral Turkish territory." This unpopular restriction pushed the round-trip flight to more than 2,600 miles, far beyond the range of any bombing mission in history. The pilots were instructed to drop their bombs from an altitude of 30,000 feet.

Recalled Captain John Payne, pilot of Black Mariah, "To us the briefing was straight out of 'The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.' Many of our ships could never make thirty thousand feet with an extra bomb bay tank and six five-hundred-pound bombs. And range...!"

When the 'official' briefing concluded and the briefing officers had left the room, the Halpro navigators broke into a steady buzz of discontent and disbelief in the mission they had been delegated. The unhappiness was broken only by the entrance of Colonel Halverson. The Halpro commander produced a worn map that had been provided for the mission, a map heavily creased on what would be a direct line from Egypt through Turkey and the Black Sea. To his men, he announced, "Can we help it if the National Geographic put this line through Turkey?" For the first time, the navigators smiled. "Furthermore," Hurry-Up Harry continued, "I suggest that we bomb at fourteen thousand feet."

The first American bombing mission over Europe began when thirteen Halpro B-24s took off from an R.A.F. airstrip at Fayid, Egypt, at ten-thirty on the night of June 11, 1942. As a night flight, destined to put the bombers over Ploesti with the first rays of dawn, it was impossible to maintain a flight formation. Each pilot was on his own, navigating through the dark skies over the Mediterranean while hoping to find his comrades when the morning sun rose over the Black Sea.

One of the thirteen bombers was forced to turn back to Egypt when frozen fuel transfer lines cut power to three engines. The remaining twelve continued on towards Ploesti where they dropped their bombs on what was believed to be the large Astra Romana refinery.

In fact, the first raid on Ploesti was unremarkable and inflicted only minimal damage to the Romanian refineries and German oil supply. The mission, however, represented a significant step for American airpower. Not only were these the first bombs dropped over Europe by Americans, but it was also a demonstration of the great range the B-24 afforded for Allied operations. Of the twelve Liberators that reached Ploesti, six landed safely in Iraq (the designated recovery point for the mission) and two landed in Syria. Four bombers were forced to land in Turkey where the aircraft were seized and the crews interned. The only injuries were minor, and not a single man was lost or killed in action.

Few people beyond the crews that flew the mission and the enemy soldiers in the targets below them, ever knew that the mission had been launched. Three days after the raid the New York Times reported on Turkish dispatches under a headline that read: U.S. Bombers Strike Black Sea Area -- Base Is Mystery. Had the target been identified, the mission would probably still have remained a mystery. Few Americans beyond Allied war planners had ever heard of Ploesti.

Nine days after taking off to bomb Ploesti the Halverson Project was dissolved and its assets were renamed the First Provisional Bombardment Group of the Middle East Air Force (MEAF) under command of Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton. In the months that followed the crews (minus the men held in Turkey) conducted regular combat operations in the Mediterranean. Most missions were flown against Italian shipping in North African ports that provided the enemy supply line to General Erwin Rommel's Afrika Corps. In the four months before the British breakthrough at El Alamein, the bomb group rarely had more than two dozen planes in the air.

Nevertheless, the determined air-warriors attacked targets in the harbors of Tobruk and Benghazi, Navarino Bay (Greece), and throughout the Mediterranean. They destroyed 60% of the fuel, food, and ammunition being shipped to Axis forces in North Africa.

On October 31, 1942, the First Provisional Bombardment Group became part of the newly activated 376th Heavy Bombardment Group. As the first heavy bombardment group to operate in the Middle East Theater, the 376th took great pride in its status and history, adopting the nickname "Liberandos" after their B-24 Liberators. Throughout the winter, Halpro crews escaping from Turkey slowly made their way back to join the Liberandos. (By April 1943, all had returned to duty.)

On October 31, 1942, the First Provisional Bombardment Group became part of the newly activated 376th Heavy Bombardment Group. As the first heavy bombardment group to operate in the Middle East Theater, the 376th took great pride in its status and history, adopting the nickname "Liberandos" after their B-24 Liberators. Throughout the winter, Halpro crews escaping from Turkey slowly made their way back to join the Liberandos. (By April 1943, all had returned to duty.)

On November 12 following the successful American invasion of North Africa code-named Operation Torch, the Middle East Air Force was re-designated. It became the 9th U.S. Army Air Force.

In any combat operation, there are commanders who get the headlines, heroes who capture the imagination, and heroic actions that become the subjects of books and movies. Behind the scenes, there are also thousands of untold stories, men who quietly went about their duties with unrecognized and unpublished valor and dedication. Such seemed to be the early fate of the 9th Air Force, despite its role as the first combat air unit to begin operations in Europe, and the historic long-range mission to Ploesti in the summer of 1942. By the end of the first year of World War II, most Americans were well acquainted with Ken's Men in the Pacific. Few had ever heard of Harry Halverson, the Liberandos, or the 9th Air Force.

In the first half of 1943, it was the Mighty Eighth that captured headlines with daring missions over Germany, interesting heroes like Maynard Snuffy Smith, celebrity missions by Clark Gable, and the feisty General Ira Eaker. Even the new 12th Air Force under General Jimmy Doolittle, established to support Operation Torch and the subsequent invasions of Sicily and Italy, was better known than the men of the 9th.

If General Brereton's pilots and crews were somewhat miffed at their lack of notoriety, it certainly did not show in their production. They continued bombardment of enemy targets in North Africa with dedication, and then joined the 12th Air Force in support of missions across the Mediterranean. Along the way, the 9th Air Force developed some interesting heroes of its own--they were just not as well-known prior to August 1, 1943, when the 9th made Air Force history.

Killer Kane

Among the 9th's early legends was Colonel John Riley Kane, better known as Killer Kane, commander of the 98th Bombardment Group.

The B-24s and aircrews of the 98th arrived at Ramat David, Palestine on July 20, 1942, to join the Liberandos in the MEAF. Kane had been with the Group since its inception the previous January. On November 11, the day before the MEAF became the 9th Air Force, the 98th Bomb Group moved to Fayid, Egypt, and soon thereafter began calling itself the Pyramidiers to denote their Middle-East operations. On December 29 Colonel Kane became the Group's third commander.

The B-24s and aircrews of the 98th arrived at Ramat David, Palestine on July 20, 1942, to join the Liberandos in the MEAF. Kane had been with the Group since its inception the previous January. On November 11, the day before the MEAF became the 9th Air Force, the 98th Bomb Group moved to Fayid, Egypt, and soon thereafter began calling itself the Pyramidiers to denote their Middle-East operations. On December 29 Colonel Kane became the Group's third commander.

John Kane grew up the son of Reverend John Franklin Kane, who for twenty-one years pastored the Southside Baptist Church in Shreveport, Louisiana. His big, barrel-chested son while brash and outspoken, had a soft-side and gentle nature nurtured in his youth. His history as the son of a minister may provide some insight into his distaste for his war-time nickname. Killer Kane, despite his boisterous and demanding demeanor and often profane out-spoken diatribes, was a man with a soft side and paternal dedication to his men.

Legend often relates that the title Killer Kane was given him by German fighter pilots who had witnessed his fearlessness in the cockpit. Mildred Sisk, called Axis Sally by the GIs in Europe, referred to Killer Kane from time to time in her daily "Home Sweet Home" propaganda broadcasts from radio Berlin. Despite his distaste for the nickname, it stuck with him. To his chagrin, his Pyramidiers loved the moniker and reveled in its every use though none dared speak it in Kane's presence.

The legend aside, the Killer Kane moniker was actually born long before the war when the young man was a standout football player for Baylor University. He graduated from Baylor in 1928 and soon thereafter joined the Army Air Corps. During his cadet days, he became close friends with a fellow cadet named Rogers, and the duo became known as Killer Kane and Buck Rogers after the popular comic strip of the time. This second affirmation of the moniker resulted in a permanent title that would follow him throughout his exciting life.

John Kane earned his wings in 1932. He reverted to reserve status in 1934 but the following year returned to active duty. His leadership skills led to quick promotion and the admiration of his men, despite his often brash and demanding manner. Recalled Norm Whalen who flew as Kane's navigator in Europe, "He was a controversial figure, and he told the higher-ups what he thought. Colonel Kane was very direct and outspoken. He expressed himself without holding back on what he felt."

Colonel Kane wouldn't hesitate to shout his orders or opinion to anyone...including the enemy. During one Pyramidier mission, the intrepid commander was leading a mission over an Afrika Corps target when his tail and top turret guns jammed at the height of diversionary attacks by German Messerschmitts. The problems caused him to miss his bomb headings but, despite the loss of his guns, he looped to make another run over the target while shouting orders over the open radio for the rest of his B-24s to follow his lead. Enemy fighter pilots got on his frequency and began to drown out Kane's command with their own taunts. Unfazed, Kane shouted, "Get the hell off the air, you bastards!" Incredibly, even the Germans obeyed Killer Kane's orders, and with a now-clear channel, he continued to direct his squadron in completing their mission.

By July 1943 Colonel John Kane had flown forty-three missions, far more than the magic thirty that sent a pilot home after duty in the Middle East. Colonel Kane also was privy to, was in fact instrumental in, planning for the 9th Air Force's most important mission to date. He was determined to personally lead his Pyramidiers in what would be their most dangerous mission. Many of his men had logged their own thirty missions, but as the plans unfolded for an August 1 raid across the Mediterranean Kane announced: "All available crews will go on the mission regardless of completion of their combat tours."

His men didn't complain; they would follow John Kane to the very gates of Hell so long as he led the way. In a 2002 interview, Norm Whalen noted, "I'd go back up with him tomorrow morning if he was still around and asked me." Such loyalty was a requisite for the August 1, 1943, mission.

Killer Kane knew he would not only be leading his Pyramidiers to the gates of Hell but through them and into the inferno beyond.

Return to Ploesti

The concept of a return mission to Ploesti developed in January 1943 at the highest level--the Casablanca Conference in Morocco attended by President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and the highest war planners of the Allied nations. The top item on the agenda at Casablanca was the land invasion of Europe and a decision to postpone a cross-channel invasion until 1944 in favor of a march across the Mediterranean through Sicily and Italy to penetrate Germany from its soft belly to the south. Operation Tidal Wave, the return to Ploesti, became a footnote to the invasion plan developed, albeit an important one. It was estimated that a successful bombing raid against Ploesti could deny Hitler a third of his fuel production and thereby shorten the war by six months.

Tidal Wave emerged from the Casablanca Conference as a good idea that no one could reasonably expect possible to achieve. The Allied High Command issued top-secret orders to General Brereton that his 9th Air Force should bomb Ploesti in the interim between the end of the North Africa campaign, estimated to be only months away, and the subsequent invasion of Sicily. Authors James Dugan and Carroll Stewart noted in their benchmark account Ploesti, "It (Tidal Wave) was one of the few instances in World War II in which the High Command handed down a major task to a theater commander without asking him if it was feasible."

Though the mission itself was assigned to the 9th Air Force, the planning began in the office of Air Chief General Hap Arnold. Arnold sent Colonel Jacob Smart, one of his most trusted strategists and an experienced pilot, to Britain to work out the details. Ultimately, it was Smart who developed the overall logistics of the mission, including the nearly unprecedented recommendation that Ploesti is bombed at a low level.

The challenge was a formidable one and Colonel Smart made good use of his Intelligence Services. He enlisted the advice of British Lieutenant Colonel W. Lesley Forster who had managed the large Astra Romana refinery at Ploesti for eight years prior to the war and had first-hand knowledge of the target.

Among the myriad of Tidal Wave planning challenges was the selection of targets for the raid. The target was NOT Ploesti, a city inhabited by 100,000 Romanian citizens. Many of these civilians were not happy with the German occupation and privately supported the Allied advances.

The target for Operation Tidal Wave was Ploesti's nearby Axis oil supply.

The city itself was ringed with rail lines that connected more than a dozen large refineries, the lifeblood of the local economy and the fuel for Hitler's war. The challenge then was to strike the refineries across a five-mile circumference without errant bombs falling on the civilian population. This factor, more than any other, precipitated Colonel Smart's initial concept for a low-level mission.

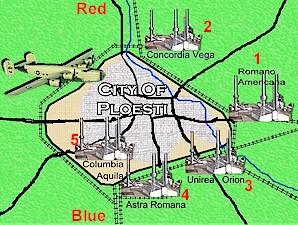

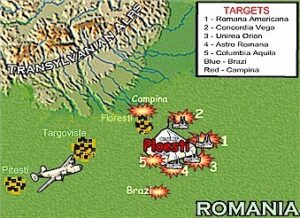

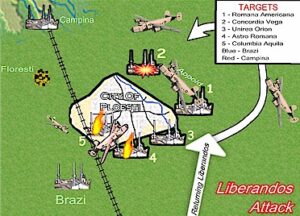

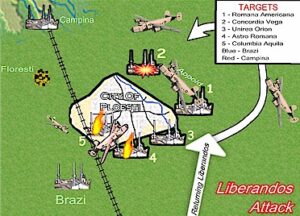

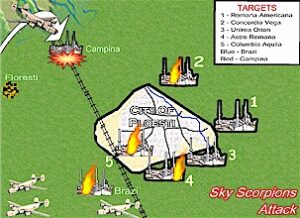

Smart hoped that as many as 200 B-24 Liberators would be available for Operation Tidal Wave. It was an optimistic outlook that was, nevertheless, too small a force to strike all of the refineries that circled Ploesti. With the first-hand insight of Colonel Forster, five primary facilities were selected and numbered Target White 1 - 5. With the bombers launching from Libya, 200 miles closer than the first Ploesti mission and in a direct line over the Mediterranean and across Greece, the formation was plotted to approach the city from the west instead of the Black Sea as the Halpro Group had done.

Smart hoped that as many as 200 B-24 Liberators would be available for Operation Tidal Wave. It was an optimistic outlook that was, nevertheless, too small a force to strike all of the refineries that circled Ploesti. With the first-hand insight of Colonel Forster, five primary facilities were selected and numbered Target White 1 - 5. With the bombers launching from Libya, 200 miles closer than the first Ploesti mission and in a direct line over the Mediterranean and across Greece, the formation was plotted to approach the city from the west instead of the Black Sea as the Halpro Group had done.

As these tactical considerations developed, two additional targets were added. The Steaua Romana facility eighteen miles north of Ploesti at Campina was designated Target Red. The Creditul Minier facility at Brazi five miles south of the main objectives was designated Target Blue. The latter produced the highest quality aviation fuel in Europe.

By May the North Africa Campaign was drawing to a close. The important port of Tunis fell to Allied Forces on May 7, and by May 13 all Axis forces in North Africa surrendered. In accordance with the plan developed at the Casablanca Conference, Allied efforts focused on the invasion of Sicily. To map out that campaign, code named Operation Husky", Roosevelt, Churchill, and their top war planners met in Washington, D.C., in May for the Trident Conference. It was there that Colonel Smart presented his plans for a low-level bombing raid on Ploesti.

Generally, as at Casablanca, Tidal Wave became a footnote to the meetings. Though the High Command had called for the raid, its significance was overshadowed by the larger concerns of Operation Husky. U.S. Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall did note that even "a fairly successful attack on Ploesti" would stagger Berlin, but there was little discussion on the tactical plan. The decision as to whether the mission would be a low-level or high-altitude attack was left to the mission commanders--more specifically, General Eisenhower, 9th Air Force commander General Brereton, and General Uzal Ent who commanded the 9th Bomber Command.

Eisenhower approved the mission and its time table without issuing an opinion on the high-vs.-low employment of the bombers. Colonel Smart to returned to England to take the next steps in planning the mission. Nearly simultaneously he had to convince Brereton and Ent that the B-24s should bomb at roof-top level.

The mission was assigned to the 9th Air Force, meaning the attacking force would be the Liberandos (376th BG), now under command of Colonel Keith K. Compton, and Colonel Kane's Pyramidiers (98th BG). To supplement these assets the two experienced B-24 groups assigned to the 8th Air Force were to be detached for service in Egypt, as was the 8th's soon-to-arrive 389th Bombardment Group.

Ted's Traveling Circus

The 93rd Bombardment Group (Heavy) was activated on March 1, 1942, as a B-24 combat unit. Operating under Colonel Edward Ted Timberlake, the Liberators spent the spring and early summer flying antisubmarine missions in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. On September 7, 1943, the 93rd moved to Alconbury, England, to join the Flying Fortresses of the 8th Air Force. In December the 93rd moved to Hardwick, but a large contingent of the group's Liberators was sent to North Africa on temporary assignment to the 9th Air Force in support of the desert war.

Reunited at Hardwick in February 1943 after receiving a Distinguished Unit Citation for operations in North Africa, the 93rd became the focus of a news story in Yank magazine. The reporter, Sergeant Carroll "Cal" Stewart, was restricted from publishing the identity of the group so when he wrote his 2-page story he titled it: "Ted's (after Edward Timberlake) Traveling Circus. It was an appropriate moniker for the group that so often was called upon to take its show on the road--three major deployments outside of England in the course of the war. Thus, the title stuck, even after Colonel Smart selected Timberlake to be his operations officer for Tidal Wave.

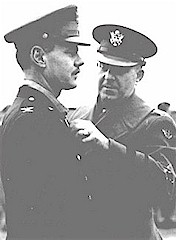

After accepting the challenging new position, on May 17 Timberlake promoted one of his squadron leaders, Colonel Addison Earl Baker, to command the Traveling Circus.

After accepting the challenging new position, on May 17 Timberlake promoted one of his squadron leaders, Colonel Addison Earl Baker, to command the Traveling Circus.

At age 21, Addison Baker had enlisted in the Army in 1929 from his hometown of Akron, Ohio, where he worked as an automobile mechanic. He served nearly a year as an enlisted man before being accepted as a flying cadet. In February 1931, he received his wings and commission as a second lieutenant. The following year, however, budget cuts forced him back into the private sector. He built and ran his own business, a service station, in Detroit, Michigan, while continuing to serve the Army Air Corps as a member of the Ohio National Guard.

When Baker was called to active duty in November 1940 he trained as a B-24 pilot, was promoted to major, and became commander of the 93rd Bombardment Group's 328th Squadron. When the 93rd deployed to England, Baker traveled with the group to become Ted Timberlake's operations officer, as well as to fly fifteen combat missions. By the time he assumed command of the Traveling Circus he was a lieutenant colonel.

Colonel Timberlake's new assignment as commander of the 201st (Provisional) Combat Wing, and his job of preparing five squadrons of B-24s for Operation Tidal Wave, was daunting. Again, he turned to the men of his Traveling Circus, appointing one of his most experienced squadron leaders to serve as his own operations officer. Major John Jerstad was a former high school teacher in St. Louis, Missouri, who enlisted as an aviation cadet in July 1941. Seven months later he received his wings and commission on February 6, just two months after Pearl Harbor. He served first in the 98th Bombardment Group and became a charter member of the 93rd when it was formed.

Colonel Timberlake's new assignment as commander of the 201st (Provisional) Combat Wing, and his job of preparing five squadrons of B-24s for Operation Tidal Wave, was daunting. Again, he turned to the men of his Traveling Circus, appointing one of his most experienced squadron leaders to serve as his own operations officer. Major John Jerstad was a former high school teacher in St. Louis, Missouri, who enlisted as an aviation cadet in July 1941. Seven months later he received his wings and commission on February 6, just two months after Pearl Harbor. He served first in the 98th Bombardment Group and became a charter member of the 93rd when it was formed.

The Wisconsin native and graduate of Northwestern University was an odd mix of academia and brute warrior. As a Liberator pilot, he flew every available mission, exceeding the required 25 missions early in the war--and then continued to fly. It is said he flew so many missions that by the time he became Tiberlake's chief operations officer, no one could estimate his grand total. Jerstad the academic, while not keeping track of his missions, kept a notebook in which he studiously noted each lesson learned from every mission, every bombing run, and every attack by enemy fighters. He was also justifiably proud of his accomplishments and his rapid promotion to major, writing his parents after accepting his new position, "I'm the youngest kid on the staff and it's quite an honor to work with colonels and generals."

As the preparations for Operation Tidal Wave began in May, though the mission was assigned to the 9th Air Force in North Africa, it was the two B-24 groups assigned to the 8th Air Force in England that set the pace. Joining the Traveling Circus in the Ploesti raid was the group's almost-friendly rivals in the Mighty Eighth, the 44th Bombardment Group.

Flying Eight Balls

Calculating that four plus four equals eight, the 44th Bombardment Group adopted the nickname, Flying Eight Balls. More than one member of their rivals in the Traveling Circus, however, referred to them as Flying Screwballs. Typical inter-unit rivalries aside, when Sergeant Steward did his story on the Flying Circus for Yank magazine, the editors erringly included B-24 photos of the 44th Group. The airmen of neither group were pleased with the result.

The Flying Eight Balls had been in combat for nearly a year when they were tasked with joining the 93rd in the trip to the Mediterranean and Operation Tidal Wave. Since February the pilots had been commanded by a character equal in courage and personality to the Pyramidiers' "Killer Kane."

The Flying Eight Balls had been in combat for nearly a year when they were tasked with joining the 93rd in the trip to the Mediterranean and Operation Tidal Wave. Since February the pilots had been commanded by a character equal in courage and personality to the Pyramidiers' "Killer Kane."

Born in Missouri in 1904, Colonel Leon William Johnson was old enough to be the father of many of the young men who flew with him in the Flying Eight Balls. In his own youth, at age eighteen, he was appointed from Kansas to the US Military Academy at West Point. He graduated as an Infantry officer in 1926, six years ahead of Colonel Timberlake.

Born in Missouri in 1904, Colonel Leon William Johnson was old enough to be the father of many of the young men who flew with him in the Flying Eight Balls. In his own youth, at age eighteen, he was appointed from Kansas to the US Military Academy at West Point. He graduated as an Infantry officer in 1926, six years ahead of Colonel Timberlake.

After three years on the ground, Lieutenant Johnson transferred to the Army Air Corps. Upon receiving his wings, he spent five years piloting observation aircraft, then gave up his temporary rank as captain to attend Cal Tech and study meteorology. Thereafter, he served as a weather officer at Barksdale Field in Louisiana, before training to fly bombers out of Savannah, Georgia. When the 8th Air Force was activated in June 1942, Leon Johnson was one of four initial flying officers and one of the first to arrive in England. Flying far more than his own share of missions, Colonel Johnson's awards rivaled those of John Kane's including the Silver Star and two Distinguished Flying Crosses.

When the Traveling Circus and Flying Eight Balls began low-level practice flights along the English coast late in May, Colonel Johnson was quick to voice his opposition to low-level bombing and equally prompt in obeying his orders. Recalled Robert Lenhausen, one of his pilots, "This (training) was right after a very mean and costly mission we'd made against the submarine pens at Kiel where we lost seven out of eighteen ships. And a few days before, a squadron of speedy B-26 medium bombers had tried a low-level raid on Holland and none came back. There were much murmuring and grumbling. Colonel Johnson told us in a calm, positive voice that if it was the desire of the Air Force to fly low-level missions, we would fly those missions and he would lead us.

There was complete silence in the room.

"If he was leading, we were going to follow."

On June 11 the 389th Bombardment Group under Colonel Jack Wood arrived in England to become the 8th Air Force's third B-24 bomber group. Calling themselves the Sky Scorpions, the unit arrived with factory-fresh Liberators and untested pilots and crews. They had little time to get acquainted with their new airfield at Hethel, England. By the end of June, all three of the Mighty Eighth's B-24 groups flew to Egypt, first to support "Operation Husky", and then to make a daring low-level raid on a target so secret that only the key planners knew its name.

Colonel Wood's Scorpions, as well as the other four groups now assigned to General Ent's Ninth Bomber command, flew their first combat mission out of Benghazi, Libya, on July 9. The missions targeted Sicily and surrounding areas, softening the enemy-held region for the land invasion that began with paratroopers late that same night. The full-scale amphibious assault followed with the dawn of the next day.

To disrupt the Axis supply line and support to the embattled enemy forces on Sicily, on July 19 General Jimmy Doolittle led 158 B-17s from his 12th Air Force in a bombing mission against targets around Rome. It marked the second attack on the capital of one of the three major Axis powers. Both had been led by the daring reserve officer from California. Doolittle's attack was supported by 110 of General Uzal Ent's Liberators, granting additional combat experience to the rookies of the Sky Scorpions. On the day following the mission into Italy, Ent took all five squadrons of the Ninth Bomber Command off operations. The target date for the launching of Tidal Wave was only ten days away.

For security purposes and to protect the identity of Tidal Wave's target, the airmen of the 9th Bomber Command were quarantined. The airfields that were spread around Benghazi were closed and heavily guarded. In the center of the complex, a green hut became the source of mystery. On the day Doolittle had bombed Rome, a detailed set of scale models depicting the refineries at Ploesti were flown to Benghazi from England, and set up in the green hut. Only the top commanders and the men tasked with planning the mission were allowed into the green hut.

In the desert beyond Benghazi, a larger, nearly full-scale layout of the Ploesti refineries was marked out in the sand with white lime. Hastily-erected telephone poles were planted in the sand to represent smokestacks. During the pre-mission quarantine, all five bomber groups flew low-level practice missions to drop wooden bombs on what would become their assigned targets. The whole scenario gave the pilots and crews, who did not yet know the name or location of their mission, a grave sense of foreboding. The mysterious green hut, the ten-day quarantine, the strange practice missions over the desert, and the absolute secrecy indicated only that whatever their mission was, it was going to be important...and dangerous!

Those privy to the secrets of Tidal Wave were even more concerned that their men who could only guess at the nature of the mission. Major Alfred Kalberer, operations officer of the Liberandos, was a savvy combat veteran of 46 missions including the Halpro raid on Ploesti. After being briefed on the return trip to Ploesti in late June he stated, "This thing can't work. I'll have nothing to do with it. I figure we'll lose thirty-two planes." Kalberer was relieved and sent back to the United States. (Kalberer later returned to combat in the Pacific, commanded a B-29 group, and rose to the rank of major general.)

During the last week of preparations General Ent was even more pessimistic, despite the fact that in a full-scale dress rehearsal against the mock-up refineries in the desert, the bombers had destroyed their targets in only two minutes. He sent a letter to General Brereton estimating that losses for the actual mission would be seventy-five aircraft. Since by this point it was estimated that 150 Liberators would fly the Ploesti raid, the assessment predicted fifty per-cent losses.

Brereton had little choice in the matter by that point, having passed Colonel Smart's plan for the low-level raid on to General Eisenhower, who had approved it. Flying into Benghazi from his headquarters in Cairo on Friday, July 30, the 9th Air Force commander noted to his aid Colonel Louis Hobbs, "This is where the Ninth Air Force makes history or wishes it had never been born. Hap Arnold has handed us a tough one." After arriving in Benghazi, he greeted his men in anticipation of Sunday's raid.

"Gentlemen, I am the only person I know of who has held a commission in both the Army and the Navy. I have seen the fleet steam up the Hudson and I have seen the corps of cadets pass in full-dress parade. These sights are soul-stirring. But today, as I saw your hundred seventy-five four-engined bombers come roaring across the African desert at fifty feet altitude, bringing dust from the ground with your mighty roar, I enjoyed the great thrill of my entire life.

"Tomorrow, when you advance across that captured country, you will tear the hearts out of them. You are going in low level to hit the oil refineries, not the houses, and leave your powerful impression on a great nation. The roar of your engines in the heart of the enemy's conquest will sound in the ears of the Romanians--and, yet, the whole world! --long after the blasts of your bombs and fires have died away."

As darkness fell over the Libyan desert, even General Brereton's inspiring words could not push away the doubts and fears of the 1,700 men tasked with bombing the refineries at Ploesti. Still ringing in Colonel Kane's ears were the words of General Ent who had estimated fifty percent casualties but been denied his request to alter the plan and bomb Ploesti from the shelter of the high clouds. Despite the fact that Ent planned to fly with his bombers and would be an integral part of the conduct of the mission, in a private conversation with Kane he had noted:

"If nobody comes back, the results will be worth the cost."

Black Sunday (August 1, 1943)

When the first of 178 Liberators began taking at 5:00 A.M. on the morning of Sunday, August 1, 1943, it marked the culmination of months of planning and more than a week of detailed practice. Operation Tidal Wave may well have been the most thoroughly planned and intricately briefed air mission in history, and was to be led by what was probably the most experienced leadership ever assembled. Every officer from the Ninth Air Force commander on down, planned to fly with his men. Despite all this planning and preparation, the devil was in the details.

On Saturday afternoon Hap Arnold cabled General Brereton with orders that neither he nor Colonel Smart fly the mission--both men were too highly placed and knew too many Allied war plans and secrets to be risked. Brereton, despite his distaste for the order, recognized its reason and gave similar orders to his chief operations officer. Colonel Timberlake was meeting with Gerald Geerling, an Intelligence Officer who had become Tiberlake's chief architect for the mission, when Brereton's order reached him. Geerlings recalled, "Timberlake's face became grim and he cursed softly but vehemently. There were tears in Timberlake's eyes. 'God, my men will think I'm chicken,' he said."

The last-minute order forced a rapid reshuffling of the crews. Compton's Liberandos had been delegated the lead position in the flight. Brereton had planned to fly in the command ship Teggie Ann with mission leader Keith Compton, and Compton's co-pilot Ralph Thompson. With Brereton out, General Uzal Ent was shuffled to Teggie Ann to command the overall mission from a stool in the cockpit behind Compton and Thompson. Teggie Ann's navigator for the mission was Captain Harold Wicklund, who was returning to Ploesti, having flown the first mission with Halpro.

Before the shuffle General Ent had planned to direct the mission from the co-pilot's seat of John Kane's Hail Columbia. The move left the 98th BG commander to find a new co-pilot. Similarly, the grounding of Colonel Smart left Major Kenneth Dessert of Addison Baker's Traveling Circus to find a replacement for his right seat.

During the shuffle Colonel Timberlake urged John Jerstad, scheduled to fly co-pilot for Baker, not to fly the mission. Jerstad was so far beyond his quota missions it was an unreasonable risk. Furthermore Jerstad, despite his work as Tiberlake's chief operations officer, had been unassigned since June and was more-or-less a floater awaiting transfer home.

Jerstad insisted on one more mission, perhaps recalling the briefing Addison Baker had given the men of his group. "We're going on one of the biggest jobs of the war," he told them. "If we hit it good, we might cut six months off the war. She may be a little rough, but you can do her. I'm going to take you to this one if my plane falls apart."

The shuffle of crews continued throughout the late-night, complicated by a bout of dysentery that had stricken a third of the men at Benghazi earlier in the week. Despite the toll taken by the disease, only two men were grounded including Colonel Leon Johnson's co-pilot leaving the Eight Balls' commander to find a last-minute replacement. Furthermore, the ground crews had managed to make three additional bombers flight-ready, bringing the striking force to a total of 178 bombers. This welcome news necessitated additional volunteers.

That every Liberator that took off from Benghazi on the early morning of August 1 was fully manned, stands as a tribute to the determination and courage of the American airmen. Nine of Colonel Kane's bombers were piloted by rookie crews borrowed from the newly arrived Sky Scorpions. Among them was First Lieutenant Thomas Fravega, a pilot assigned to the 389th BG. Lieutenant Fravega had recently arrived with his crew at Benghazi by transport. Begging for any aircraft, he was assigned an old bomber named Wahoo and added to Kane's formation. His radioman was Technical Sergeant Fred Fravega, his kid brother.

Early Sunday morning a man-made dust storm engulfed Benghazi, generated by the turning propellers or 712 engines as the first of 178 Liberators in five formations began taking off from the multiple fields around the base. One of the last of the Liberandos developed problems as it lifted off and turned back to make an emergency landing. Striking a pole, it crashed hard killing all but two members of the crew. These were the first casualties. Before Black Sunday ended there would be many more.

The loss of one bomber aside, the remainder of the takeoff went well and within the hour the remaining 177 Liberators were winging their way across the dawn-sparkled Mediterranean. Among the first in the lead formation was B-24 Wongo-Wongo, flown by First Lieutenant Brian Flavelle. Flavelle was close to the magic thirty having just returned from Sicily where he had been shot down on his twenty-eighth mission and successfully evaded enemy forces. Back in the United States, he had a four-month-old son he had never seen.

Across the broad Mediterranean, the flight of bombers continued, seeking landfall near the enemy-held island of Corfu. After three hours in the air, landfall was imminent for the first two groups (the Liberandos and the Flying Circus.) Further back and out of visual range, General Ent could only hope the remaining three groups were following. Due the critical need to maintain strict radio silence, he dared not verify that all his bombers were still moving steadily towards Corfu.

Shortly before landfall, Wongo-Wongo began to fly erratically. Without explanation, it suddenly nosed up with on its tail, hung suspended for a moment, and then rolled over on its back to fall into the sea below. Flames engulfed the wreckage and spread over the sparkling water. Thirty seconds later it vanished. Brian Flavelle would never return home to see his child.

Shortly before landfall, Wongo-Wongo began to fly erratically. Without explanation, it suddenly nosed up with on its tail, hung suspended for a moment, and then rolled over on its back to fall into the sea below. Flames engulfed the wreckage and spread over the sparkling water. Thirty seconds later it vanished. Brian Flavelle would never return home to see his child.

Despite pre-mission orders not to break formation First Lieutenant Guy Iovine, on Flavelle's wing, dove down to sea level to survey the scene and look for survivors. His impromptu mission of mercy was a wasted effort; there were none. To make matters worse, the overloaded B-24 was unable to gain altitude to rejoin the formation. Lieutenant Iovine was forced to turn back to Africa, leaving the remaining 175 bombers to continue on over Greece and to negotiate the steep Pindus Range. Only hours into the mission three aircraft had been lost, not to the enemy, but to common, unexplainable circumstances that seemed to plague almost any aerial mission.

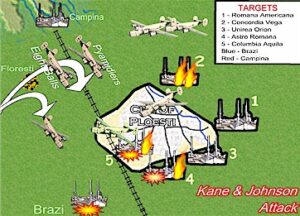

In the lead bomber Colonel Compton had seen neither the crash of Wongo-Wongo or the resultant loss of Iovine's bomber. Continuing to lead the way overland, the Liberandos pressed on towards their target with the Traveling Circus behind them. Unseen, but still en route further back, were John Kane's Pyramidiers. They were trailed by Leon Johnson's Eight Balls with Jack Wood's Sky Scorpions bringing up the rear. The mission was still intact, but the formation had been dangerously split into two echelons.

Over the sea and then over Greece mechanical failures forced five of Addison Baker's Liberators to turn back to Africa, leaving the Circus with thirty-two bombers to complete a mission that included attacks on two refineries. The loss of Compton's two bombers over the sea left him with twenty-six Liberators to bomb Romana Americana. For all General Ent and Colonel Compton knew, these were all that remained of the 178 aircraft that had taken off that morning. Determinedly they forged ahead to climb the 9,000-foot Pindus Range, continuing onward at an altitude of 11,000 feet.

Further back a determined Killer Kane was doing his best, in vain, to catch up. His forty-seven Pyramidiers had lost one bomber on take-off and en route to target seven more were forced to turn back. Kane had no more certainty that the first two groups were still ahead of him than Ent and Compton had that the three trailing groups were still inbound. Further, Kane knew that if Compton and Baker reached Ploesti well ahead of him, the enemy would be alerted and well-prepared by the time his bombers arrived over target. Shaking off the unknown he powered ahead, onward and upward over the Albanian mountain range. The thirty-nine Eight Balls and twenty-nine Scorpions did their best to keep up with him.

Many written accounts of the split-formation that developed en route to target blame the distance between Colonel Compton's lead formation and Colonel Kane's trailing formation on differences in altitude resulting from their different approach to the cloud cover over the mountains. Author and Ploesti veteran Robert Sternfels notes, however:

"The idea of (Colonel Kane) using what some call 'Frontal Penetration' maneuver to fly through the weather after we turned at the island of Corfu is not true. No such maneuver was tried. When Colonel Compton reached the weather, he flew through the clouds at 11,000+, or, a few feet in a loose formation as did Colonel Kane.

"The idea that Colonel Compton climbed to 16,000 feet to clear the clouds is wrong. Some claim that by climbing to 16,000 feet he caught a tail wind which caused a separation of the first section. Nothing could be further from the truth. Compton did not climb above 11,000 feet.

"The real reason for the space between the groups was a matter of power settings. Kane and Compton differed on how to fly the B-24. Each man had strong feelings toward the amount of power to use on missions. Kane was trying to conserve engines by reducing power settings--thus air speed. Both men were right. Someone should have had a profile done on both men to see what would happen when flying together on a mission.

With Compton's air speed at 175 and Kane's at 160, it wasn't long before Kane's group, being behind Compton's, had a 60 mile plus separation."

When Compton's Liberandos broke out of the mountains and dropped into Romanian air space he was indeed, more than 60 miles ahead of Colonel Kane. A recipe for disaster was in the making, but every man understood the importance of the mission. Beyond the mountains and along the foothills of the Transylvanian Alps, the Liberandos and Flying Circus descended to tree-top level to make the last leg of their run beneath the enemy radar.

All knew that the only ally the American fliers had, and the only hope of completing their mission and returning home alive, lay in the element of surprise. What they couldn't know was that the Germans already knew they were coming, had indeed tracked the massive formation from the moment they lifted off at Benghazi.

The enemy was well aware that a major bombing raid had been mounted. Across the Mediterranean, they had tracked the 177 Liberators. When the formation reached Corfu, spotters had announced their direction sending German forces throughout the region into a second-stage alert. As the bombers made landfall and continued north over Greece, Axis forces went to third-stage. In the Romanian capital of Bucharest Major Ernst Kuchenbacker phoned his commander, Brigadier General Alfred Gerstenberg, at his weekend mountain retreat. "It is unclear what is developing," he advised the man who commanded one of the most heavily defended cities in Europe, "but we think the objective must be Ploesti." Immediately Gerstenberg headed back to the city to command its defense.

As many as 200 Axis fighters were in the vicinity of Ploesti, including four wings (52 planes) of ME-109s at Mizel, twenty miles east of the city. All pilots were put on alert for immediate takeoff, with spotters already in the air. More than 200 big anti-aircraft guns ringed the city limits to protect the refineries, including 88-mm flak guns and 37-mm and 20-mm rapid-fire cannon. Well-trained German gunners heard the sounds of the sirens and rushed to their stations, ready to rain death on the Americans they now believed were heading towards them. Across the city barrage balloons were raised on their explosive-laden steel cables, to snare wings and destroy the bombers that might soon arrive.

One hundred fifty miles away over the lush farmland, the leading two bomber groups hugged the ground as pilots and navigators watched for the first of their three I.P.s (Initial Points) at Pitesti. Minus their two primary route navigators, the Liberandos did well and were soon passing the small village from which friendly Romanians welcomed them with smiles and waves of the hand. The serene blue sky broken only by an occasional rain cloud as well as the peacefully rolling hills and farms below belied the danger that lay ahead.

One hundred fifty miles away over the lush farmland, the leading two bomber groups hugged the ground as pilots and navigators watched for the first of their three I.P.s (Initial Points) at Pitesti. Minus their two primary route navigators, the Liberandos did well and were soon passing the small village from which friendly Romanians welcomed them with smiles and waves of the hand. The serene blue sky broken only by an occasional rain cloud as well as the peacefully rolling hills and farms below belied the danger that lay ahead.

The three I.P.s created a straight line, first Pitesti and then Targoviste twenty miles from the final I.P. at Floresti. Floresti lay on a series of railroad tracks between Ploesti and Target Blue at Campina. The inbound pilots planned to follow the railroad tracks into the northwest entrance of the city, Compton's Liberandos leading to bomb Target White 1 (Romana Americana) on the east side of the city. Meanwhile, Colonel Baker's Flying Circus would divide into two attacking forces to bomb Target White 2 (Concordia Vega) and Target White 3 (Unirea Sepranta) which lay on either side of Compton's target.

Nothing had been seen of the other three bomb groups since departing Benghazi but, assuming they were still inbound, they were to follow the same entry point. Kane's Pyramidiers were to hit Target White 4 (Astra Romana) while the Leon Johnson's Eight Balls split up to hit Target White 5 (Columbia Aquila) on the southwest side of the city, and Target Blue at Brazi five miles south. The trailing group, Colonel Wood's Sky Scorpions were ordered to turn north to attack Target Red at Campina, eighteen miles away.

Winding through a series of small valleys that lay between Pitesti and Targoviste, the lead wave found themselves confronted by a number of small villages. Breaking out over the second I.P., Colonel Compton mistook the combined road, river and railway leading south out of the small town for the similar features at Floresti. "Now," he shouted to his pilot Red Thompson, directing the 127-degree heading plotted for the bomb run into Ploesti. Reggie Ann headed south. The lead ship was not flying into Ploesti but was twenty miles southwest of the entrance point on the road leading to the Romanian capital of Bucharest.

Behind Teggie Ann the other pilots quickly recognized the blunder, but due to the radio silence, could not contact Compton. In G.I. GINNIE Norman Appold, who would later earn a Distinguished Service Cross for the Ploesti raid, decided the error was grave enough to break that discipline. "Not here! Not here!" he shouted over the radio.

Flight leader Ramsey Potts in Duchess chimed in with, "Mistake! Mistake!"

It was difficult for a formation of twenty-five large bombers flying nearly wingtip-to-wingtip to execute a turn back to the north. At 250 miles per hour Colonel Compton's lead flight was half-way to Bucharest before General Ent, now shouting orders in the clear over the radio himself, managed to get his bombers headed back to Ploesti. By that time the ground fire had begun, and enemy fighters were moving in to join the fray.

Ploesti

Coming Back is Secondary

Behind both the Liberandos and the Flying Circus, which had followed the lead group when it made the wrong turn at Targoviste, a lone B-24 was attacking Ploesti from the west. Piloting Brewery Wagon, First Lieutenant John Palm chose not to turn southeast at Targoviste when Compton gave the order. Convinced the turn was in error, by the time shouts of "Mistake!" echoed in the headsets of the bombers, Brewery Wagon was approaching Ploesti alone from the west. The sole target of the guns below, the Liberator took a direct hit on its Plexiglas nose killing the navigator and bombardier.

With one engine destroyed and two on fire Lieutenant Palm struggled to keep his bomber on course, determined to make his bombs count. "Tramping on the pedals was like fighting a bucking horse," he recalled. "I was not getting much pressure on the right pedal. I reached down. My right leg below the knee was hanging from a shred of flesh."

Palm jettisoned his bombs just west of the city to try and fight his way home, even as a German Messerschmitt raked deadly fire from tail to the bomber's shattered nose. Brewery Wagon went down in a field southwest of Ploesti, where Palm's copilot and engineer carried him out of danger. His war over, the courageous pilot was imprisoned by the Germans. (Palm's leg was subsequently amputated. When he was repatriated, however, his handicap could not keep him from flying. A successful businessman for decades after the war, he piloted his private jet for years until his death in 1993.)

2:50 P.M. (Ploesti Time)

Directly behind Compton's Liberandos when they made their errant turn at Targoviste was Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker's Flying Circus. Five of Baker's B-24s had been forced to turn back during the flight to Romania, leaving thirty-two Liberators to strike the two briefed targets, Concordia Vega (2) north of the city and Unirea Orion (3) east of Ploesti while the Liberandos hit Romana Americana (1) located between the two.

Directly behind Compton's Liberandos when they made their errant turn at Targoviste was Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker's Flying Circus. Five of Baker's B-24s had been forced to turn back during the flight to Romania, leaving thirty-two Liberators to strike the two briefed targets, Concordia Vega (2) north of the city and Unirea Orion (3) east of Ploesti while the Liberandos hit Romana Americana (1) located between the two.

Piloting Hell's Wench with his volunteer co-pilot John Jerstad, Baker sensed the error of the lead formation's turn at Targoviste, but turned with them anyway to maintain formation. Because of the radio-silence being maintained, Baker could not know for sure if the turn had been made in error or if General Ent had made a last-minute change in the tactical approach for the bomb run.

Flying at a high rate of speed toward Bucharest and only yards above the ground, it was difficult to detect any landmarks. Passing south of the target city however, Baker looked to his left and noted smoke rising into the sky from distant refineries. It was time to make a critical decision, and the combat-savvy commander of the Circus understood what he had to do.

"There was no doubt about his decision," recalled Lieutenant Russell Longnecker who was flying Thundermug in the formation behind Baker. "He maneuvered our group more eloquently than if he had radio contact with each of us. He turned left ninety degrees. We all turned with him. Ploesti was off there to the left and we were going straight into it and we were going fast."

93rd Bomb Group

Traveling Circus

Ltc. Addison Baker & Maj. John Jerstad

Baker's sudden decision split the attacking forced into two groups moving in opposite directions. Twenty-six B-24s under Colonel Compton (Liberandos) were still flying southeast towards Bucharest while Baker's thirty-two bombers wheeled off into the northeast to attack Ploesti. A controller in General Gerstenberg's command post in the city noted, "It's a simultaneous attack on Bucharest and Ploesti! Damned cleverly done. They send planes to tie up fighters at Bucharest while the main force hits Ploesti."

Ironically, despite the compounding misfortunes and errors that plagued the seven waves of American bombers in Operation Tidal Wave, the American airmen would respond with such courage and initiative that the German surprise would turn into utter amazement. Conduct of the broken raid was accomplished so incredibly that, on the ground, enemy forces assumed the raid had been planned that way.

Baker's thirty-two Liberators executed a text-book turn towards target, forming tightly into three waves only fifty feet above the fields of hay and corn below. To Baker's right (east) was Lieutenant Colonel George Brown's formation, and further east Major Ramsay Potts lined up his ten bombers for their own run. Initially, Potts had been briefed to attack Unirea Orion (Target White 3) while the rest of the Flying Circus attacked Concordia Vega (Target White 2) further north. The planned approach from the northwest had been plotted because Intelligence reports indicated General Gerstenberg would likely expect any potential attack as coming from over the Black Sea (as Halpro had done), and place his heaviest defenses south and east of the city. It was directly into those heavy defenses that Baker now led his airmen.

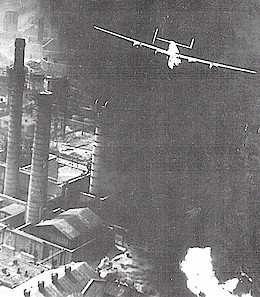

At 230-250 miles per hour it only took Baker's formation five minutes to traverse the fields below to the target city, but those five minutes were deadly. Below the bombers and often level with them because of the lowness of the approach, innocent-looking haystacks dissolved to reveal hidden enemy gunners. Top turret gunners accustomed to firing upwards to thwart attacks from enemy fighters found themselves trying to force the angle of their big 50-caliber machine guns downward into ground forces. It was an air/ground battle, unlike anything American airmen had ever encountered.

Short-fused anti-aircraft fire filled the landscape at point-blank range while scores of barrage balloons were raised, and in many cases lowered, over Ploesti to snag the wings of the incoming raiders. The running battle-damaged nearly every one of Baker's inbound bombers; several of them falling to earth before reaching the city. It was obvious that the battered Liberators could never survive the full breadth of the city to the assigned target. Noting the high smokestacks of the Columbia Aquila refinery (Target White 5) in the distance, Addison Baker homed in on it. Columbia Aquila was the briefed target of Colonel Johnson's 44th Bomb Group, but no sign of the Eight Balls or Colonel Kane's Pyramidiers ahead of them had been seen since takeoff.

Hell's Wench was still three minutes from Columbia Aquila when John Jerstad felt a tug at the wing of the lead bomber as it snagged a balloon cable. Both he and Colonel Baker fought the controls to remain on course, then struggled to correct when the cable parted while ripping away sections of wing. Simultaneously, the enemy gunners below scored with a direct hit on the nose of the lead bomber with a massive 88 round, shattering Plexiglas and killing the bombardier.

Hell's Wench immediately took three more hits, one puncturing the right-wing fuel tank to release a stream of burning aviation gasoline and another puncturing the Tokyo tanks inside to engulf the fuselage with flame. One crewman managed to leap out through the nose wheel hatch and following pilots saw his parachute open as they zipped past. Meanwhile, Hell's Wench somehow managed to roar onward towards the twin stacks of the refinery.

Two minutes from target Baker's plane was a flying inferno but the intrepid pilot and his co-pilot somehow managed to remain on course. Still, beyond the city, an open field lay between them and the target that would have afforded ample opportunity for a controlled crash-landing, but Baker never wavered. The two leaders jettisoned their bombs to enable them to remain airborne, then set to the task of leadership they had promised when Baker briefed his men with the words, "I'm going to take you to this one if my plane falls apart."

Two minutes from target Baker's plane was a flying inferno but the intrepid pilot and his co-pilot somehow managed to remain on course. Still, beyond the city, an open field lay between them and the target that would have afforded ample opportunity for a controlled crash-landing, but Baker never wavered. The two leaders jettisoned their bombs to enable them to remain airborne, then set to the task of leadership they had promised when Baker briefed his men with the words, "I'm going to take you to this one if my plane falls apart."

Even as the massive twin-stacks of Columbia Aquila loomed in his shattered cockpit window, Baker felt Hell's Wench shudder beneath another direct hit. Flying as navigator for Captain Raymond Walker in Queenie a short distance behind, Lieutenant Carl Barthel recalled,

"Baker had been burning for about three minutes. The right wing began to drop. I don't see how anyone could have been alive in that cockpit, but someone kept her leading the force on between the refinery stacks. Baker was a powerful man, but one man could not have held the ship on the climb she took beyond the stacks."

Baker and Jerstad tried to climb, but only after leading their men directly over the target. Hell's Wench struggled to get up to 300 feet where burning crew members were seen tumbling out in a desperate attempt to parachute to earth. Meanwhile, Utah Man, the sole surviving bomber in the first wave, dropped the first bombs of Tidal Wave on the massive refinery below.

Baker and Jerstad remained in the cockpit but their efforts were futile. Shortly after the bodies of their crew were seen exiting the Hell's Wench, the tangled wreckage of their Liberator fell over on its flaming right-wing. In the plummet back to earth she missing the parallel bomber Queenie by only a few feet. That bomber was piloted by Lieutenant Colonel George Brown, bringing in the second wave. "Flames hid everything in the cockpit," he marveled as he remembered the leadership of Addison Baker and his volunteer co-pilot. "Baker went down after he flew his ship to pieces to get us over the target."

None of the crew of Hell's Wench survived, including the man who had leaped from the nose wheel before reaching the target.

While the surviving bombers of Baker and Brown's flights were turning the Columbia Aquila refinery into an inferno, Major Ramsay Pott's "B Force" flight of twelve Liberators were approaching Astra Romana (Target White 4). Pott's briefed target was Unirea Speranta (Target White 3), interlaced with the Standard (Oil Company of America) Petrol Block, further east of his position.

Major Pott's new route of approach from the southwest put the huge Astra Romana plant, the largest oil producer in Europe and the primary objective of Tidal Wave, between his inbound bombers and their assigned target. Smoke from the fires at nearby Columbia Aquila masked the southern approach to Ploesti, and a curtain of anti-aircraft fire erupted all around and just above the target. The former economics professor who had graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of North Carolina only two years earlier, fearlessly led his bombers into the inferno.

Storage tanks erupted to add the flying shrapnel of their metal tanks to the maelstrom, and tank tops whipped through the air like flying Frisbees, capable of cutting a bomber in half. Bombs fell as determined pilots held their course and bombardiers refused to take their eyes off-targets only feet below. Many of the bombs were set with delayed fuses to allow the bombers to pass before they exploded, but many detonated prematurely. Despite the fact that few landed where they could do much damage to the massive Astra Romana refinery plant itself, Pott's wave engaged numerous enemy ground positions and turned the plant into a scene of deadly confusion. Added to the danger was the volcanic eruption of the smaller storage tanks beyond the plant, ignited by incendiaries tossed out by the Liberator crews.