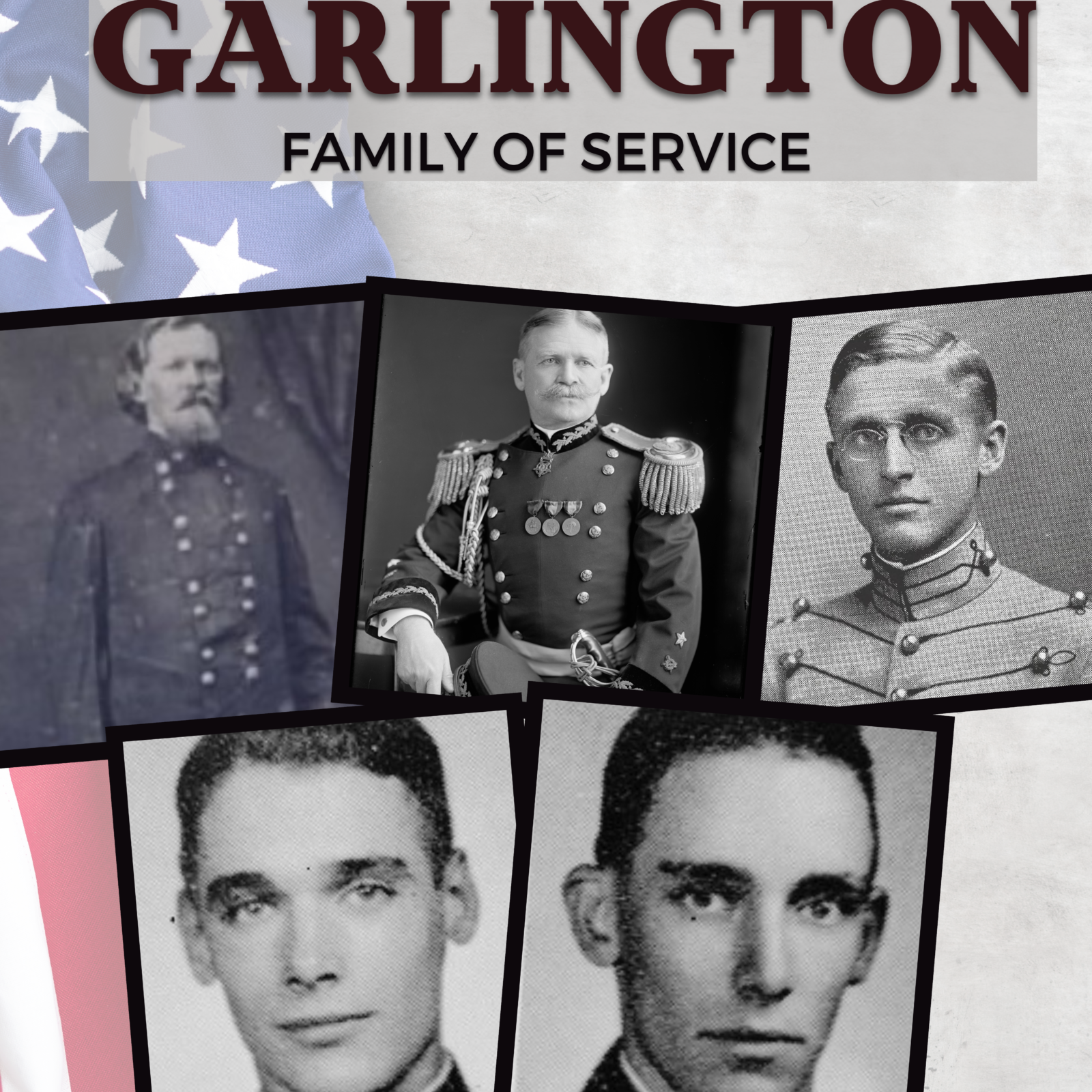

Garlington Family of Service

By: James G. Fausone

From the American Civil War to World War II, the Garlington family served the country in notable and infamous ways. The family also made the ultimate sacrifice to protect American freedoms and liberties. The Garlington family history traces its roots back to England and Wales. The American family roots were in the South. But as a military family for over a century, they have lived all over the United States and the world. Members of the Garlington family were on active service to the country for roughly 106 years.

Values and purpose are often passed down through generations either intentionally or by quiet example. The Garlington family certainly passed along the value of military service and the purpose of protecting their community.

Albert Cresswell Garlington

It started with Albert Cresswell Garlington who was born in 1822 in Georgia. He graduated from the University of Georgia with high honors in 1842. As a proud southerner, when the American Civil War broke out in April 1861, Albert firmly supported his State of South Carolina and the Confederacy.

The Governor tapped him to protect the coastline as part of the Department of the Interior. He was responsible for coastal defense and the militia. As duties were transferred to the Confederate States Army, the Governor appointed Albert Garlington brigadier general of the 3rd Brigade of South Carolina Volunteers. In 1862, the Governor appointed Garlington as adjutant general and inspector general of the South Carolina militia with the rank of Major General.

In late 1864 and early 1865, Garlington's brigade was sent to oppose the forces of Union Major General William T. Sherman as they marched through South Carolina. Garlington's brigade evacuated the state capital of Columbia, South Carolina, upon the approach of Sherman's forces and Garlington disbanded the brigade in February 1865. Sixty days later the war was over, the South had lost.

Albert ran and won political office in the South Carolina House of Representatives for two years. He then went on to practice law and was a gentleman farmer. His legacy was his son Ernest Albert Garlington born in February 1853.

Ernest Albert Garlington

Ernest was a boy of 12 when the South lost the Civil War. His father was a college graduate, a Major General, an elected politician, and a lawyer. That is a lot to live up to, and Ernest certainly did.

It might be no surprise that Ernest had a strong upbringing including education that led to his attending his father's alma mater, the University of Georgia in 1869. It was surprising that he left the university before graduating to accept an appointment to the United States Military Academy. While West Point was popular in the South prior to the Civil War, the wounds were just beginning to heal when Ernest made the move to West Point in service of the U.S. Army. He graduated from the academy in 1876.

West Point graduates dominated the highest ranks in both the Federal and Confederate armies during the Civil War. As reported by the West Point website:

"After the Civil War, the Academy entrenched itself in its success, where tradition and austere discipline ruled the Corps of Cadets for the next several decades. During this time, African-American cadets entered the Academy and endured "silencing" - the practice of isolating unwanted cadets and intimidating them to resign. Henry O. Flipper succeeded against institutional prejudice to graduate in 1877. Two other Black Cadets graduated by the turn of the century. During this era, young, commissioned officers served in the Indian Wars on the frontier army, facing the tough realities of guerilla warfare against skilled warriors."

As a freshly minted Second Lieutenant, Ernest was assigned to the 7th Regiment of the United States Cavalry. This was a time when horse cavalry was the pinnacle of warfare. This was a storied unit that was involved in the Battle of Little Bighorn, also known as Custard's Last Stand, which occurred July 25 and 26, 1876. He did not physically join the unit until after the Battle of Little Bighorn, which occurred several weeks after his appointment.

The U.S. Army of that time was involved in the so-named Indian Wars. Federal troops were used to protect settlers moving west and taking land/resources from Native Americans. The displacement of Native Americans and resettling onto reservations was the order of the day. At the time, the Army with its rifles and cavalry was arrogant about the ability of the Indians to win the fight. Custard's Last Stand was a wake-up call. The Battle of Little Bighorn, in Montana Territory, pitted federal troops led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876) against a band of Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. Tensions between the two groups had been rising since the discovery of gold on Native American lands. When a number of tribes missed a federal deadline to move to reservations, the U.S. Army, including Custer and his 7th Cavalry, was dispatched to confront them. Custer was unaware of the number of Indians fighting under the command of Sitting Bull at Little Bighorn, and his forces were outnumbered and quickly overcome.

This loss to the 7th Cavalry would have been stinging, but it created an opportunity for quick promotion for green lieutenants like Ernest. He continued to serve in the Indian Wars including at the infamous Battle at Wounded Knee. On December 29, 1890, Garlington was injured while fighting in the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota. Ernest Garlington received the Medal of Honor on September 23, 1893, for distinguished gallantry. Wounded Knee was another end of the pendulum from Little Bighorn.

Over 130 years later, controversy still swirls around Wounded Knee and the Medals of Honor that was awarded. The Army engaged a band of Lakota Indians at Wounded Knee creed South Dakota in December 1890. Who shot first is lost to history, but the deaths of approximately 350 Lakota, including women and children, and 30 Army troops made it one of the bloodiest engagements of the Indian Wars period. The Army calls it a battle; the Lakota call it a massacre. Multiple times, the Lakota have sought to have an apology issued, reparations, and revocation of the 20 Medals of Honor awarded as a result of the battle.

U.S. Army Colonel Samuel L. Russell (Ret.) explained on Veterans Radio in 2019, the background of a bill introduced into Congress, H.R. 3467, called "Remove the Stain", asking Congress to take up the issue of whether or not the men who were awarded Medals of Honor as a result of the battle at Wounded Knee in December of 1890 should be revoked. The Lakota Nation has taken up for at least two decades the cause of seeing those medals as a stain on American history and on their heritage specifically. Over the years, they've made a number of resolutions calling for those medals to be rescinded.

Today's modern Medal of Honor is nothing like it was during the Indian Wars or the Civil War. As Russell explained:

"When you consider that there's no Bronze Star, there's no Silver Star, there's no Distinguished Service Cross, the award of a number of Medals of Honor was not out of line. Col. Russell, the Medal of Honor obviously had a different meaning at the time to these soldiers. If you read the newspaper accounts of soldiers receiving the Medal of Honor, it's clear that the civilians don't really know or understand what the Medal of Honor is yet. It does not have the prestige that it gains later. There are no White House ceremonies with the President presenting the medal himself. They are engraved and then mailed to the unit and the unit presents it however they want to. Usually in a formation, sometimes on a parade field."

Unlike modern Medal of Honor citations that have a recitation of facts associated with the action, Ernest's simply states:

MEDAL OF HONOR CITATION:

"Rank and organization: First Lieutenant, 7th U.S. Cavalry. Place and date: At Wounded Knee Creek, S. Dak., December 29, 1890. Entered service at: Athens, Ga. Born: February 20, 1853, Newberry, S.C. Date of issue: September 26, 1893.

Citation: Distinguished gallantry."

Garlington's actions at the Wounded Knee Creek dry ravine that morning were highlighted in greater detail in an article in the New York Times some years later. "In the battle, Garlington had drawn his revolver, rallied his men, and was directing a return fire, steadying his force by his example of cool commands. A rifle ball tore through his right arm, smashing his forearm and elbow and the lower part of the upper arm. He fell, bleeding badly, but remained conscious. From the ground, he continued to direct his men."

A more details description was given in 1892 by Colonel Forsyth:

"The Indians, upon the opening of the fight, rushed for the ravine, but Capt. Garlington with his party, having seized the road crossing, held it so well that not an Indian escaped in that direction without having to leave the ravine and thereby expose himself to a galling fire from other troops. As a consequence, only a very few did escape. There was gathered with him there one officer, four noncommissioned officers, and five privates, but the shelter behind the banks of the road was of such a character that only about four men at a time could avail themselves of it and fire, whilst every time they fired they were partially exposed. However, Capt. Garlington promptly took his place among the fighting men and kneeling in plain view of Indians who, not 30 yards away, were pouring a galling fire into his little party, he continued the fight against overwhelming odds and held the ravine. Of the 11 men composing his party, 3 were killed and 3 wounded, but he held his position, emptied a Winchester rifle (private property with which he had armed himself before the fight), and then, taking the carbine of a private, he continued shooting (while the private supplied him with cartridges from behind) until he himself was knocked over by a bullet. He has finally led away, very weak from loss of blood. Sergt. Adam Neder, Troop A, Seventh Cavalry, who, in this same list with Lieut. Hawthorne, is granted a medal of honor, was a member of this party, and was kneeling shoulder to shoulder with Capt. Garlington at the time he (Neder) was wounded."

Ernest would continue on in the service of the U.S. Army until 1917 a period of 27 years after Wounded Knee. The Medal of Honor and controversy over Wounded Knee keep Ernest’s actions relevant today. It is easy to overlook his military service which took him across the world. He went to exotic postings in Cuba, the Philippines, and Germany.

In 1898, Garlington served as inspector general in Cuba during the Spanish–American War and participated in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. He again served as inspector general from 1899 through 1901 in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War. He served in the inspector general position again, this time as a Colonel, in the Philippines from 1905 to 1906.

The final promotion for Ernest Garlington was to Brigadier General, Inspector General of the Army, on October 1, 1906, after which he served on the General Staff of the Army. In 1908, he conducted the army investigation into the Brownsville Affair. This was an incident of racial discrimination by Brownsville, Texas residents against Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Brown.

The Buffalo Soldiers served with distinction during the Indian Wars. The name Buffalo Soldiers was given by Cheyenne warriors. Notwithstanding service and reputation, in many areas the soldiers faced discrimination. In July 1906 that reached a boiling point outside Fort Brown, Texas along the Mexican border. Tensions were running high and townspeople blamed a shooting on a dozen Buffalo Soldiers. A U.S. Army investigation questioned all 167 soldiers at the fort and there was no evidence of them leaving the fort that night. Nevertheless, bowing to pressure, President Teddy Roosevelt ordered all 167 Black soldiers dishonorably discharged. Many of these men had served for over a decade and six had been awarded the Medal of Honor. Congress intervened to right this wrong in 1972 and it exonerated the Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry of the charges leading to a dishonorable discharge.

In 1911, Ernest Garlington was an observer of the German Army Maneuvers. he retired due to age on February 20, 1917, but continued to serve in the office of the Chief of Staff from April 30 to September 21, 1917. Ernest would live the life of a retired general officer until his death on October 16, 1934. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

His wife, Anna Buford Garlington, bore him a son that continued the military legacy - Creswell Garlington, Sr.

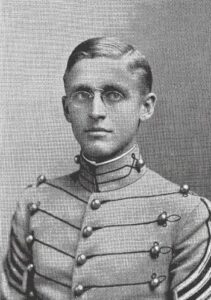

Creswell Garlington, Sr.

One of the challenges of a military family is the constant moving from a post or fort to a new state. Ernest's son Creswell was born in Rock Island, Illinois in 1887. Creswell had a family tradition to live up to that included military services like his dad and granddad.

Creswell had the pedigree to obtain an appointment at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He was a member of the Class of 1910. His military career would be defined by World War I and he would support efforts in WWII. In September 1918, while in France with the 77th American Expeditionary Forces, he would receive a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism.

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE CROSS CITATION:

"The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Lieutenant Colonel (General Staff Corps) Creswell Garlington, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with General Staff, 77th Division, A.E.F., near MErval, France, 14 September 1918. In preparation for an attack by units of his division, Lieutenant Colonel Garlington helped establish an advanced observation post. Learning a wounded officer was in front, Lieutenant Colonel Garlington helped establish an advanced observation post. Learning a wounded officer was in front, Lieutenant Colonel Garlington made his way twice through intense fire from artillery and small arms to where the wounded officer lay and assisted in carrying him to safety."

Creswell was promoted to Brigadier General in July 1942. Most of his Army career was in the engineering corps including Commanding General of the Engineering Replacement Center at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri. He died of natural causes in March 1945 while attached to Headquarters of the 7th Service Command. His service extended over 30 years.

Creswell carried on the family tradition by siring two boys, Creswell, Jr., and Henry Fitch Garlington. They would carry on military service in the country. This time it was in duplicate as the twin boys followed the family business.

Creswell Garlington, Jr.

Creswell, Jr., and his twin brother, Henry, were born in Paris, France, in 1922 to father, Creswell, Sr., and mother, Elise Alexandrine Fitch Garlington. While Cres was named after his father, his brother inherited his mother's maiden name. After Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war with Japan and Germany in December 1941. Boys and men of age knew they would join up or be drafted. The surge of patriotism resulted in a wave of males joining the Army and Navy The Garlington twins were 19 when war broke out and it was simply a matter of time before they swore the oath of allegiance to the United States as the Garlington men before them had.

Creswell, known as "Cres", found himself as a member of the Citadel Class of 1944, the class that never was because of World War II. His twin brother Henry was in the abbreviated class of 1945. They both left the Citadel to join the war effort.

Although not the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, to which his father and grandfather attended, the Citadel's reputation in South Carolina then as today turns out officer qualified graduates.

As the Commandant of Cadets Colonel Thomas J. Gordon, USMC (Ret.) explained on Veterans Radio in 2022:

"The Citadel's mission is to educate and develop principal leaders that will be successful in all walks of life. The Citadel is the ultimate leadership lab. You talked about whether leaders are made or are leaders born. Well, I think we all can agree that while there are a few naturals out there, most of us have developed our leadership skills through the school of hard knocks. The Citadel offers just that, right? It's an intense, rigorous program but it affords them the opportunity to lead their peers. We have these five leadership laboratories - there are five battalions and the corps cadets are given the opportunity for the corps to run the corps here. I firmly believe that if you can lead your peers, you can lead anybody. The Citadel from your average university is that leadership laboratory - the ability to develop men and women of virtue in character and turn those leaders back to society."

Cres joined the Army infantry and his brother went to the Army Air Corps. Cres as a platoon leader would need basic infantry skills, an eye for terrain, situational awareness, knowing the strength/weaknesses of his troops, an understanding of tactics, good communication skills, and excellent navigational skills. Like most platoon leaders at the time, he was an untested Lieutenant whom his men had to respect and rely on. Cres was in the action and at considerable risk like all platoon leaders. he was wounded in action in December 1944 and died days later from those wounds at the 91st Evacuation Hospital at the tender age of 22.

The Garlington family made the ultimate sacrifice for the nation. Creswell Garlington, Jr., was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. The citation reads:

"The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Second Lieutenant (Infantry) Creswell Garlington, Jr. (ASN: 0-547375), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as a platoon leader, Company I, 335th Infantry Regiment, 84th Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces from 29 November to 1 December 1944. Second Lieutenant Garlington's platoon was temporarily stopped during an attack by the fire of four enemy machine guns approximately three hundred yards away. He crawled forward and with hand grenades eliminated two of the positions while a member of his platoon eliminated the other two. Later the same day, he and one of his men broke up enemy patrols which tried to infiltrate through their lines. On 30 November 1944, during an enemy counterattack, he and four of his men crawled to an advantageous point and killed or wounded sixty of the enemy. On 1 December 1944, Second Lieutenant Garlington carried a wounded member of his platoon through intense enemy artillery fire to a place of safety. While directing the fire of his men, an artillery shell hit approximately ten yards away. While at the aid station he insisted that others less seriously wounded be treated first and tried to show his men the position of a concealed enemy machine gun. Second Lieutenant Garlington's intrepid actions, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty, exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 84th Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

Headquarters, European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army, General Orders No. 24 (1945)"

This young unmarried Lieutenant was the end of this branch of the family tree.

Henry Fitch Garlington

In fairness, Henry was also swept along by world events. Henry graduated from Solebury School in New Hope, P.A. a college preparatory boarding school. That summer, he applied to the Army Air Corps for pilot training. While waiting for the assignment, he attended The Citadel where his brother was in the prior class.

The glamour spot in World War II was no longer in cavalry units like in Henry's grandfather's day but in aviation. Henry was drawn to flying. He completed his pilot training and was assigned to North Africa. He was a hot-shot pilot with a plane named "Betty".

He flew a P-40 and was based near Naples, Italy. He flew 40 missions in Italy before his luck ran out. He was strafing a truck convoy when shot down and captured. Members of the truck convoy took him to a tree to hang him but a German officer intervened thinking the aviator may have valuable intelligence. Henry was sent to Stalag Luft III POW camp ninety miles east of Berlin where he spent over a year as a POW.

After liberation by American troops from the stalag and a period of recovery, he was sent to Air Corps training command as a flight instructor at the end of the war. In 1949, he married Jeanne Hunter Morrell of Savannah. In 1955, he retired as a Captain from the Air Force and moved back to Savannah where he lived the rest of his life working for the City and then in the banking industry. He passed away in February 2019.

Neither of his two daughters followed him into military service. Henry was the last of the Garlington family tree to be in active service.

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED