Maynard H. "Snuffy" Smith

You Don't Have To Be A Saint To Be A Hero

July 15, 1943, it was a highly unusual day for the men of the 8th Air Force's 306th Bomb Group stationed at Thurleigh in Bedfordshire County, England. The 306th had been one of the first American bomb groups to reach the European theater, arriving from Boise, Idaho, in September 1942. For nearly a year, the heavy bombardment group had been at war and the young American airmen had seen just about everything. Little, however, could match the buzz of excited interest and serious preparation for a visit by Secretary of War Henry Stimson on this summer day at the airfield north of London. It was to be a day of "firsts", a high-level and widely-publicized recognition of the efforts of the 8th Air Force's valiant efforts to turn back the tide of Nazi aggression in Europe.

Pilots of the 306the flew their first combat mission on October 9, 1942, against the locomotive works at Lille, France, and suffered the loss of their first B-17 and its crew. Sadly, in the months that followed, all too many more Flying Fortresses and their daring airmen would fall to anti-aircraft fire and enemy fighter planes. These missions were often deep into occupied France against targets beyond the range of Allied pursuit planes so that most had to be flown without friendly fighter escort. It was a true test of the Army Air Force's belief that the heavily armed Flying Fortresses could fend for themselves and that "The well-flown air force cannot be stopped."

Despite the immense danger and extreme losses, the men of the 306th flew regularly against enemy targets and took great pride in their accomplishments. The men called themselves "The Reich Wreckers" though the Group's official motto was "Abundance of Strength". Following a January 27, 1943 mission to Wilhelmshaven, Germany, the men of the 306th became known as "First Over Germany". (Other bomber groups including the 303rd Bomb Group participated in that first raid into Germany itself, but as the lead formation, the 306th laid just claim to this distinction.)

Six weeks before the Secretary of War's visit to Thurleigh, men of the 306th had flown a dangerous mission against the submarine pens at St. Nazaire and fought their way home through a hail of enemy flak and fighter gunfire. One airman, a gunner on one of the 306th Flying Fortresses, had distinguished himself by great valor and unbelievable determination on the trip home. Though heroism was a common commodity on nearly every mission the 8th Air Force flew, this particular soldier's actions resulted in his nomination for the Medal of Honor - on his first mission!

On July 12, general orders were issued in Washington, D.C., awarding our nation's highest military medal to Lieutenant Jack Mathis and Sergeant Maynard Smith, two men of the 8th Air Force. Five airmen had already received the Medal of Honor in the first 18 months of the war: General James Doolittle, Captain Harl Pease, and General Kenneth Walker for action in the Pacific theater, and Colonel Demas Craw and Major Pierpont Hamilton for their actions on the ground in North Africa. Only Doolittle and Hamilton had survived their moment of heroism to receive their awards from the President of the United States.

The newly authorized award to Lieutenant Jack Mathis was to be posthumously presented to his family at their hometown in Texas later in the summer, making the award to the 306th Bomb Group's Sergeant Maynard Smith in many ways:

- Awarded to an airman for heroism in the European theater of operations.

- Awarded to an enlisted airman

None of these facts were lost on President Franklin Roosevelt, who saw in this situation a great opportunity to publicize the great work of the 8th Air Force. It further provided a wonderful venue to inspire and motivate both soldiers on foreign shores and the American public at home with a true story of dramatic heroism. When the general orders were published on July 12, a dispatch was sent to the 8th Air Force Headquarters in England to advise that Henry L. Stimson would personally present the Medal of Honor to Sergeant Maynard H. Smith for his heroism on May 1, 1943. It would add one more first:

- Presented by the Secretary of War in the theater of action.

Upon learning of Secretary of War Stimson's visit to the airfield at Thurleigh, 8th Air Force Headquarters advised Washington that there was no Medal of Honor available in Europe for him to present. As a result, when Stimson departed the following morning, he carried a quickly procured Medal in his pocket to present to a man who would prove to be a most unusual hero.

No bombing missions were scheduled for the morning of the big event. Instead, 18 bombers stood ready to take off and make an impressive 100-foot low-level pass over the dignitaries assembled to honor the Air Force's newest hero. The parade ground had been meticulously prepared to impress an entourage that would include 8th Air Force Commander General Ira C. Eaker, six other general officers, and the Secretary of War. Two radio networks were standing by to broadcast the event live - all the way back to the United States. Scores of reporters had traveled to Thurleigh to witness, photograph, and report on the historic moment, including a reporter for Stars and Stripes named Andrew Rooney, who had been one of the first to interview Sergeant Smith and publish his story of heroism in the sky.

Colonel George L. Robinson, commander of the 306th Bomb Group, did all the things a good military officer must do to ready his command for such an event. The band was in place, the bombers were prepared for their flyover, sound systems were set up and checked, and the troops fell out in spit and polish dress for the occasion. Inevitably, however, some detail always seems to get overlooked in preparations for an event of this magnitude. On this day, everything seemed ready, someone suddenly noticed that the only thing missing was a hero for Secretary Stimson to decorate.

An immediate search was launched to located Sergeant Smith. Where he was found has proved to be as embarrassing to the command as the simple fact that his attendance had been overlooked in planning the award ceremony. The Army Air Force's newest hero was quickly cleaned up, dressed in a clean uniform, and dispatched to await his recognition by Secretary of War Stimson, the salutes of seven generals, and the questions of a battery of correspondents from both print and broadcast media. When Andy Rooney filed his story, it was printed in the following day's edition of Stars and Stripes under a most unusual headline: "Medal of Honor Winner Snuffy Smith Found! On KP!"

The fact that America's newest hero had been found scraping leftovers from the metal breakfast trays after being placed on KP for disciplinary reasons provided reporters an interesting angle for their stories, but it was a situation that would have been no surprise to the men of the 306th Bomb Group. Sergeant Maynard Harrison Snuffy Smith had a reputation for being a less-than-circumspect soldier. In his 1995 book, My War, Andy Rooney recalled:

"In addition to being known as 'Snuffy,' he was known to everyone as a moderately pompous little fellow with the belligerent attitude of a man trying to make up with attitude what his five-foot-four, 130-pound body left him wanting. He posed part-time as an intellectual and loved to go to the British Pubs in Thurleigh, the small town near the base, to argue with and lecture to the British civilians who frequented. From the time he entered the Air Force he had been in some kind of trouble over one petty matter or another. 'Snuffy' was, in fact, known by the fourteen other inhabitants of his Nissen hut by an Army phrase for which there's no socially acceptable replacement. He was a real ----up."

In his own book, Mr. Rooney made no attempt to mask the common expletive that well-defines a kind of soldier who never fits in, who shirks his duty and ignores authority. Such soldiers have been portrayed in a more humorous vein with the likes of Beetle Bailey and Gomer Pyle. In the real military, such men are the misfits that cannot be changed, only tolerated; until they can be transferred elsewhere and become someone else's problem. They are certainly not the kind of soldier one expects to become a genuine hero as had Sergeant Maynard Smith. Perhaps no one in the 306th Bomb Squadron was more surprised that Snuffy Smith had become a hero in the Air Force and a household name back in America, than the disheveled little man himself.

The Life of Snuffy Smith

Snuffy Smith's great-grandfather had been a civil war soldier, a Union Army major who died in captivity as a prisoner of war. Throughout his life, Maynard Smith kept and cherished the sword that had belonged to Major Henry Harrison Smith.

When Maynard H. Smith, Jr. was born in the small town of Caro, Michigan, on May 19, 1911, he became part of the family that offered him a life of convenience and privilege. His father, Maynard H. Smith, Sr., was a successful attorney who worked for a time during the 1920s for Henry Ford and General Motors Corporation. His father's successful practice and subsequent appointment as a circuit court judge enabled the Smith family to live well during the difficult depression years. Years later, Snuffy recalled for one interviewer that his father had often said, "A man should be so rich he could go fishing all the time or so poor he had to."

With the family's comfortable financial success and his mother's busy schedule teaching grades 1-8 at a local county school, young Maynard had plenty of unsupervised time for fishing. What he caught was a reputation for being spoiled, for getting into trouble, and for being a general nuisance to those around him. He also gained the nickname "Hokie".

Perhaps to instill some sense of self-discipline in their teenage son, Judge and Mrs. Smith sent him to a military academy to finish school. Hokie Smith failed to develop the self-discipline such an experience usually instills in its students, though he did acquire a great appreciation for reading and forever thereafter fancied himself as something of an educated philosopher. When his schooling was completed, he worked for a time as a tax field agent for the Treasury Department and as an assistant receiver for the Michigan State Banking Commission. When his father died in 1934, leaving a comfortable savings account, Hokie Smith entered a period of semi-retirement at the age of 23, living with his mother in Michigan during the summer and in Florida in the winter. His time was devoted to reading: psychology, phrenology, chemistry, the history of religion, and other deep-thinking subjects.

By the time World War II began, Maynard Smith could analyze it, argue it from a human nature perspective, and psychoanalyst it from a quasi-professional point of view. At age 31, after a brief marriage that yielded a son and with Hokie still living a lazy lifestyle on his late father's money, he had no plans to personally experience the war. Both draft and a Michigan judge were poised to intervene.

The judge caught up to Smith first, pursuing him on charges of failing to pay support to his ex-wife and young son. Smith was offered two choices for his most recent transgression, join the Army or go to jail. Author/researcher Allen Mikaelian gave a glimpse into Smith's introduction to military life, quoting one of the thirty local Caro citizens who joined the Army on August 31, 1942:

"When I went into the army a group of thirty of us assembled on the courthouse steps for a picture. While we were lining up the sheriff came down the steps with Maynard 'Hokie' 'Snuffy' Smith beside him in handcuffs."

Maynard Smith managed to survive basic training with it ss structure and regimen at Sheppard Field in Texas But the 31-year-old private hated taking orders, usually from men who were ten years his junior, so he did the one thing most out-of-character to his basic nature - he volunteered! What he volunteered for was training at the Aerial Gunnery School in Harlingen, Texas. Since Army Air Force gunners were non-commissioned officers, it was the quickest way to make rank. When Smith graduated in November, he was promoted to Sergeant. After additional training in Casper, Wyoming, he was promoted to Staff Sergeant and then assigned to duty with the 423rd Squadron, 306th Bomb Group in Turleigh, England.

"Reich Wreckers"

When Staff Sergeant Smith joined the 306th Bomb Squadron (Heavy at Thurleigh in March 194, the 8th Air Force was flying an average of two missions a week to bomb targets inside occupied France and even inside Germany itself. Primary targets included railheads, air depots, and industrial plants. In accordance with the mission objectives established at the Casablanca Conference, a major priority was given to bombing submarine pens.

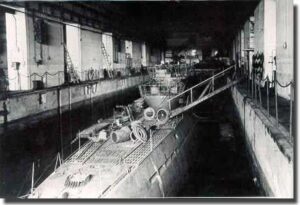

Submarine pens were large concrete bunkers built inside major ports. Here German U-Boats were steadily manufactured for deadly patrols in the North Atlantic. Battle damaged submarines also found in them an easily accessible haven to which they could return for repairs. Before the World War, began such facilities existed in Northern Germany, along the North Sea in cities like Wilhelmshaven and Vegesack. In those early days, the bunkers served to hide Hitler's war production from outside view. When the war began, these heavily-reinforced, concrete bunkers provided shelter from falling bombs.

After the fall of Paris in 1940, the Germans established similar facilities in major ports along the French Atlantic coast at Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, and continuing south to La Rochelle, and Bordeaux. These became important targets for the 8th Air Force and in the six weeks from November 17, 1942, to January 3, 1943, four of the 8th Air Force's bombing raids were launched against the submarine pens at St. Nazaire. Two missions were flown against the facilities at Lorient as well.

After the fall of Paris in 1940, the Germans established similar facilities in major ports along the French Atlantic coast at Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, and continuing south to La Rochelle, and Bordeaux. These became important targets for the 8th Air Force and in the six weeks from November 17, 1942, to January 3, 1943, four of the 8th Air Force's bombing raids were launched against the submarine pens at St. Nazaire. Two missions were flown against the facilities at Lorient as well.

Early in 1943, the Germans greatly increased the number of anti-aircraft batteries in and around these submarine pens, and shifted large numbers of fighters to the region to defend against the increasing number of Flying Fortresses General Eaker was dispatched to the region. MIssions to St. Nazaire were among the deadliest for the men of the American Air Force. As the southernmost of the three primary targets, bombers returning from St. Nazaire would have to pass the fortifications at Lorient and Brest. To minimize danger, the American pilots flew irregular paths on these long-distance missions. After dropping their bombs on St. Nazaire, the pilot first flew west over the Atlantic to bypass Brest from a distance of 80 miles and then turned east to land in England.

St.Nazaire became known to the pilots of the 8th Air Force as "flak city", and from January 4th until the end of April, only one additional mission was flown against St. Nazaire; that on February 16th. Brest and Lorient were bombed with frequency, as were other targets inside France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany.

For six weeks after his arrival at Thurleigh, Staff Sergeant Smith watched bombers take off for these dangerous missions. Most new arrivals were quickly assigned to an aircrew to replace a man killed or wounded, but Sergeant Smith managed to avoid combat duty. Though the reason for this sin to accounted for in history, from the day of his arrival at Thurleigh, Maynard Smith was something of a miss-fit, and it may well be that no one wanted to fly with him. His small frame at 5'6" tall and 130 pounds, along with his lack of military bearing, gained him the nickname, Snuffy. His personality and lack of self-discipline marked him as undesirable to a bomber crew. Most of the ten-man B-17 crews had trained together, worked together, and learned to be a close-knit team. Any new guy was an outsider who had to first prove himself. Snuffy Smith was unpopular, obnoxious, and generally viewed to be anything but a team player. Undoubtedly, no crew wanted to take the necessary risk involved in giving him the opportunity to prove himself.

Inevitably, with the heavy casualties of the demanding missions being flown, that moment had to come at last for Snuffy Smith. it came on the last day of April when a mission was announced for the following morning. Snuffy Smith was assigned to man the ball turret in the B-17 with the tail number 42-29649. The Fortress was piloted by Lieutenant Lewis P. Johnson, a veteran for whom the following day's flight would be the 25th and final mission in his tour. The other eight men of the crew were also veterans.

At 0300 hours on the morning of May 1, the assigned aircrews were awakened for the morning briefing. Despite low clouds and a drizzle of rain, the mission against St. Nazaire was announced. The sixteen assigned crews of the 306th would take off from Thurleigh to rendezvous in the air with additional bombers from the 91st, 303rd, and 305th Bomb Groups. In all, nearly eighty Flying Fortresses were scheduled to cross the French coastline and proceed to St. Nazaire to drop their bombs, then return home while skirting the deadly enemy fortifications at Brest.

May Day Massacre

Snuffy Smith was not happy about cramming his small frame into the clear Plexiglass ball turret in the belly of a B-17. Indeed, it provided its inhabitant a clear view of everything beneath but on this day as Lieutenant Johnson headed south over the English Channel there was little to see but cloud cover. Almost from the start, it seemed that the mission was doomed. Twenty Flying Fortresses from the 91st Bomb Group failed to rendezvous with the flight and were forced to cross the Channel at full throttle to catch up. The added strain forced five of them to turn back. (Ultimately, only two of the remaining 15 Fortresses were able to drop their bombs on target.)

Mechanical problems plagued the other groups as well forcing six more bombers to abort the mission. The bad weather turned back another thirty-eight pilots, leaving only twenty-nine to make the bomb run.

As the flight neared St. Nazaire, the flak began. Snuffy Smith watched the black puffs of smoke erupt around him more with amusement than fear. "First you hear a tremendous whoosh," he later candidly recalled, "then the bits of shrapnel patter against the sides of the turret, then you see the smoke." A short time later the bomb bay doors opened to release their charges and Lieutenant Johnson announced over the interphone that they were heading home. As the bomber winged out over the Atlantic, Snuffy Smith looked back long enough to see the first enemy fighters rising the challenge but it was too late. Despite the early problems in the mission, those bombers that completed their run managed to wreak heavy damage on the submarine pens below.

Tension eased inside the bomber during the short flight over the Bay of Biscane, and in the cockpit, Lieutenant Johnson and co-pilot Lieutenant Robert McCallum talked about how well the mission had gone. A short time later, the fight of returning bombers dropped down to 2,000 feet as they approached what appeared to be the coastline of Britain. For Lewis Johnson, mission 25 was almost over and he jokingly told his co-pilot, "I ought to ditch this plane just off the coast to make a dramatic story I can tell my children someday."

Unknown to him at the time, the lead navigator had miscalculated the flight home and turned east too early. Instead of crossing the English coast, the flight was flying low over the northwest peninsula of France and directly into the German guns at Brest. The sky was suddenly filled with deadly accurate flak and from his position in the Plexiglas turret, Snuffy could see one of the other Flying Fortresses falling in a pall of smoke and fire.

Too late to climb high, Lieutenant Johnson dropped rapidly beneath the flak just as the first enemy fighters pounced. In the distance, a string of 20mm cannon fire exploded in the B-17 named Vertigo which was piloted by Lt. Robert Rand of the 91st Bomb Squadron. Lieutenant Rand was instantly killed and co-pilot Major Maurice Rosener fought to control the quickly failing bomber. It was falling out of formation even as the first enemy rounds raked across the B-17 from which Snuffy was returning fire. (Five members of Vertigo's crew were killed before it ditched in 15-foot waves of the Channel, and the remaining crew was captured and interred as German POWs.)

Lieutenant Johnson was heading out over the English Channel at a low level when his own bomber was raked with enemy fire. "The slugs came all around us," recalled Lieutenant McCallum. "The whole ship shook and kind of bonged like a sound effect in a Walt Disney movie."

The stricken B-17's gunners opened up to repel the onslaught. In the ball turret, Snuffy remained unusually alert for a man on his first mission and facing his baptism of fire. "I was watching the tracers from a Jerry fighter come puffing by our tail, when suddenly there was a terrific explosion," he later told reporter Andy Rooney. "Whoomp, just like that. Boy, it was a pip," he said of the hit that ruptured the gas tanks and set the midsection ablaze.

"I knew we'd been hit," Lieutenant Johnson continued. "The plane was on fire and it wasn't flying well." In the span of a few minutes, the pilot's earlier joke about ditching the plane on his last mission so he would have an exciting war story to tell his children had come shockingly true. He quickly ordered his engineer, Technical Sergeant William W. Fahrenhold, to go back and check out the midsection of the Flying Fortress where the waist gunners and radioman would be located. When Sergeant Fahrenhold opened the door he found an impassible wall of heat and flame. Quickly closing the door he returned to advise the pilot, "I can't go back there."

The fire had destroyed all communications and Lieutenant Johnson had no way to communicate with the five men trapped in the rear of his bomber. Enemy fighters continued to swoop on the floundering Fortress that now left a trail of smoke and flame as it tried to limp home.

In the ball turret, Snuffy Smith was acutely aware that his interphone was out and his ball turret was worthless. The electrical controls that enabled the gunner in that position to maneuver the guns were out and there was nothing left to do from the cramped position below. He hand-cranked himself up to the interior fuselage and extracted his small body to find a massive fire in the radio room ahead of him - another in the tail section behind.

As an admitted agnostic since his youth, Snuffy had scoffed at the concept of Hell. Now he found himself in the middle of Hell on Earth!

Radioman Henry Bean found his small compartment totally awash in flame and promptly reached the conclusion that the bomber was doomed. This was Sergeant Bean's twenty-first mission and he was desperate to survive to complete four more. While Sergeant Smith stood in the flaming midsection of the B-17 trying to understand what was happening, Bean dashed past him.

"He (Bean) made a beeline for the gun hatch and dived out. I glanced out and watched him hit the horizontal stabilizer, bounce off, and open his 'chute," Smith recounted for Stars and Stripes. "The poor guy didn't even have a 'Mae West.' I think it was burned off."

The bomber's veteran waist gunners, Sergeants Joseph Bukackek and Robert Folliard had reached the same conclusion as Sergeant Bean. One had already jumped, the other was hung up half-in and half-out of the gun hatch. "I pulled him back in and asked him if the heat was too much for him," Snuffy continue. "All he did was stare at me and say 'I'm getting out of here.' I helped him open the rear escape door and watched him bale out. His 'chute opened okay."

With the three veteran waist gunners floating earthward into the waters of the English Channel where they disappeared for eternity, Snuffy was alone in the blazing inferno. The fate of bomber 42-29649 was now in the hands of the untested airman who had a reputation for being a total screw-up. In his 32 years of life, Maynard Smith had never made a serious decision or accomplished anything to be proud of. What he did in the next 90 minutes of unprecedented crisis above the English Channel was nothing short of remarkable.

"The smoke and gas were really thick. I wrapped a sweater around my face so I could breathe, grabbed a fire extinguisher, and attacked the fire in the radio room. Glancing over my shoulder at the tail fire, I thought I saw something coming, and I ran back. It was (Sergeant Roy H.) Gibson, the tail gunner, painfully crawling back, wounded. He had blood all over him."

Snuffy dragged Sergeant Gibson away from the flames and quickly examined him. The tail gunner had been shot in the back; his left lung pierced. Snuffy rolled the wounded man onto his left side to keep blood from filling the right lung and gave him a shot of morphine. Then he returned to try and fight the fires.

Enemy fighters had not yet given up on the floundering bomber and suddenly, Smith saw a Focke Wulf 190 lining up for another deadly pass. Snuffy dropped his fire extinguisher and bounded towards one of the waist guns to return fire. As the enemy fighter passed beneath the burning bomber, Snuffy switched to the waist gun at the other side to deliver a parting series of 50-caliber rounds. Then it was back to fighting fires once again.

Forcing his way into the radio room, where the fire was heaviest, he noticed that the intense heat had burned gaping holes through the fuselage. Through these openings, he began tossing the flaming debris to clear the area and deny more fuel to the fire. When ammunition boxes began to explode from the heat he tossed those out as well. All the while enemy fighters continued their menacing attack.

"I fired another burst with the waist guns and went back to the radio room with the last of the extinguisher fluid. When that ran out, I found a water-bottle and a urine cane and you're those out. After that I was so mad, I urinated on the fire and finally beat on it with my hands and feet until my clothes began to smolder. That FW (Focke Wulf) came around again and I let him have it. That time he left us for good. The fire was under control, more or less, and we were in sight of land."

For an hour-and-a-half, the Sad Sack of the 423rd bomb Squadron single-handedly fought off enemy fighters, tended a seriously wounded comrade, and extinguished the flames that melted steel and metal to nearly severe the bomber. "To me, it was a dream," Snuffy later proclaimed. "I had just done what I had been trained to do. I didn't know what the hell it was all about. I wasn't there to get a medal. Like millions of others, I just wanted to get it over with and get home."

He also noted, "It was a miracle that the ship didn't break in two in the air, and I wish I could shake hands personally with the people who built her. They sure did a wonderful job, and we owe our lives to them."

In fact, B-17 #42-29649 did break in two. After reaching the English coast, Lieutenant Johnson gently nursed his bomber to the first available airfield at Predannack, Cornwall. As he put the tail wheel down on the runway the stress finished the job begun by enemy fire 90 minutes earlier, and the charred remains of the Flying Fortress skidded to a halt in two sections.

There were more than 3,500 bullet and shrapnel holes in the remains of Lieutenant Johnson's bomber. One propeller was shattered, the flaps were destroyed by enemy fire, the radio room gutted by fire, the left wing's gas tank destroyed, and the nose was shattered from flak. All that was salvaged were the engines and the lives of six men. Lieutenant Johnson was quick to credit his rookie gunner stating Smith had performed "acts which, by the will of God alone, did not cost him his life, performed in complete self-sacrifice and the utmost efficiency and which were solely responsible for the return of the aircraft and the lives of everyone aboard."

The crews of seven other bombers were not so fortunate. Of the 29 B-17s that completed the May 1, 1943 mission to St. Nazaire, seven never came home. Counting the three men who jumped from Lieutenant Johnson's burning bomber and two more dead in other returning Fortresses, the toll of dead and missing was at 75. Fifteen airmen were wounded. Stars and Stripes correspondent Andy Rooney was the first to interview Snuffy after the mission. The published account quickly propelled the young man into instant stardom and he was sought out by other correspondents. It was a role that Sergeant Smith accepted, relished, and even played into well. He recounted the events of that fateful day, posed for the cameras, and assumed the position of a veteran and expert gunner to advise new arrivals. All this attention gave him a new audience to which he could also expound on his philosophical views of the world and universe.

Lieutenant Johnson promptly recommended his heroic gunner for the Medal of Honor. In the six-week period before it was approved and presented, Snuffy Smith flew four more missions and received the first of two Air Medals. he also missed at least one mission he should have flown. Returning from town late after a pass, he missed a briefing and another gunner had to be found to fly a mission for which Smith had been scheduled. It was for this infraction that Snuffy had been punished with a week of KP, the duty with which he found himself occupied when Secretary of War Stimson came to England to present him with the Medal of Honor.

The ceremony itself was quite impressive, befitting an occasion of such dignity. The brass band played and General Ira weaker announced, "Sergeant Smith not only performed his duty, he carried on after others - more experienced than he - had given up. Through his presence of mind, determination, and bravery, he saved the lives of six of his crewmates and the Fortress in which he flew."

Secretary of War Stimson stepped forward to place the Medal of Honor around Snuffy's neck while Generals saluted the diminutive and unlikely hero. Radio stations across the United States broadcast the events and listeners waited for the moment that the hero would speak himself. When that moment came, Snuffy Smith stepped to the microphone to simply say "Thank you" - nothing more.

When the ceremony concluded, the reporters pressed forward for a more substantial quote for their stories. One asked, "Isn't meeting the secretary of war and facing all the reporters' questions worse than the experience you had putting out the fire on board the Flying Fortress."

Snuffy simply answered, "No!"

Fortunately for those who had to write the story for the newspapers back home, the KP incident gave them a unique angle. Unmoved by the attention of politicians and generals, Snuffy reveled in the media attention and even posed for photographs while peeling potatoes. (though in fact, he had not been peeling potatoes while on KP) In short order, all of America fell in love with the diminutive hero who had demonstrated that valor and greatness can be found in the most unlikely of characters.

As the first enlisted airman in history to earn the Medal of Honor, and the first living airman of the European theater to receive the award, Snuffy Smith became legendary. The legend became far greater than the man, for if indeed Sergeant Maynard H. Smith became living proof that You don't have to be a saint to become a hero, his actions beyond those 90 minutes in a burning B-17 proved that Becoming a hero doesn't make you a saint! Snuffy Smith for all his faults and failures, never changed. To his death, he remained the man he always had been and didn't seem to care what anyone else thought.

At Thurleigh, he indulged himself in the attention showered his way, eagerly proffered autographs signed "Sgt. Maynard Smith, C.M.H.", and took advantage of his "hero" status to sleep late and avail himself of additional privilege. At an airfield where soldiers faced danger with each new mission and where heroism was almost so common as to become trite, Snuffy quickly wore out his welcome. He was grounded and given a desk job. In 1944, the group operations officer noted his lack of "any desire to perform his duties in a manner becoming his rank" and recommended his reduction to the rank of private. Finally, in March 1945, Snuffy Smith was sent home.

On March 22, the small Michigan town of Caro welcomed its prodigal son home with a parade and festivities that were undoubtedly well-deserved. Two months later, Snuffy Smith was honorably discharged from the Army Air Force at Miami Beach, Florida.

Much has been written about Maynard H. Smith's life in the years after his heroism in Europe. His second marriage to a girl he fell in love with in England ended much as had his first marriage. His business dealings were disorganized, usually unsuccessful, and occasionally left him with legal troubles.

As a Medal of Honor recipient, he was different from most who shared that high honor - Snuffy Smith never backed away from the role of a war hero or played down his actions. In a 1979 account titled "It Was My First Trip Out", he recounted the story of that fateful day for an issue of Sergeants magazine. In the retelling of his tale over the years, it became embellished to the point that the article had him entering the cockpit to treat a wounded Lieutenant Johnson and co-pilot, and then personally flying the bomber safely home. (In fact, a B-17 top-turret gunner named Sergeant Clifford Erickson had performed such a feat and may have inspired this version of Snuffy Smith's story.)

It is not surprising that many who have written the story of Staff Sergeant Maynard H. Smith remember him for his war stories, his unabashed hero role, and his failures in marriage and business. His infamy beyond his moment of heroism is far more interesting than a single air mission in World War II. His death on May 11, 1984, six days before his 73rd birthday, left many unanswered questions about a most amusing character. Historians will forever ask the question, "What caused a hero like Snuffy Smith to go so wrong?"

Perhaps that question can only be answered by realizing Andy Rooney's assessment of Sergeant Smith is the most accurate description of the little man's life - Snuffy Smith was a ----up. Before he joined the Army and went to war, it seemed that the little guy couldn't do anything right. Becoming a hero didn't change Snuffy Smith, he was still a ----up. Somehow, however, despite everything else that was wrong in his life, when six lives hung in the balance and a genuine hero was needed, Maynard Smith found something deep within that finally enabled him to do something right. It would be most unfair to begrudge that man the pleasure of leaving behind something good for his family, his hometown, and his nation to remember him for.

"He is a man his mother, his State, and his country can't be too proud of. Some of us will like him all the more because he isn't too good for human nature's daily food." - New York Times on July 16, 1943

About the Author

Jim Fausone is a partner with Legal Help For Veterans, PLLC, with over twenty years of experience helping veterans apply for service-connected disability benefits and starting their claims, appealing VA decisions, and filing claims for an increased disability rating so veterans can receive a higher level of benefits.

If you were denied service connection or benefits for any service-connected disease, our firm can help. We can also put you and your family in touch with other critical resources to ensure you receive the treatment you deserve.

Give us a call at (800) 693-4800 or visit us online at www.LegalHelpForVeterans.com.

This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, and educational purposes.

Copyright © 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED